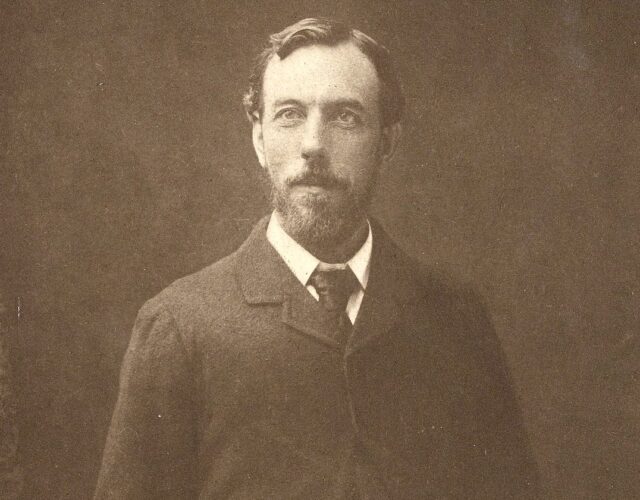

The Legacy of William Ramsay: Discovering the Noble Gases

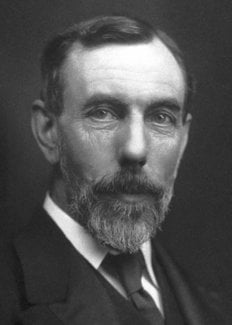

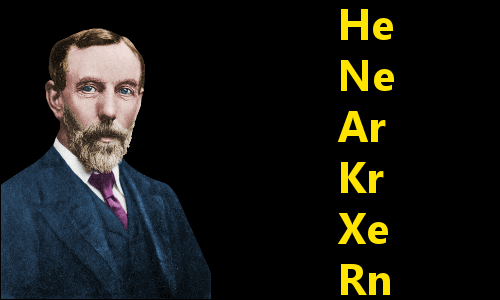

The scientific world was forever changed by the work of Sir William Ramsay, a Scottish chemist whose pioneering research filled an entire column of the periodic table. His systematic discovery of the noble gases—helium, argon, krypton, xenon, neon, and radon—fundamentally reshaped chemical theory. This article explores the life, groundbreaking experiments, and enduring impact of this Nobel Prize-winning scientist.

Early Life and Education of a Pioneering Chemist

The story of the noble gases begins in Scotland with the birth of William Ramsay. Born in Glasgow on October 2, 1852, he was immersed in an academic and industrial environment from a young age. His family's scientific background and the city's reputation for engineering excellence nurtured his burgeoning curiosity.

Formative Academic Training

Ramsay's formal academic journey saw him pursue an advanced degree far from home. He traveled to Germany to study under the guidance of renowned chemist Robert Bunsen at the University of Tübingen. There, he earned his Ph.D. in organic chemistry in 1872 with a dissertation on toluic acid and nitrotoluic acid. This rigorous training in German laboratory methods proved invaluable for his future work.

Upon returning to Great Britain, he held several academic posts, beginning at the University of Glasgow. It was during this period that his research interests began to shift. The meticulous approach he learned in Germany would later be applied to inorganic chemistry with revolutionary results. His eventual move to University College London (UCL) in 1887 provided the platform for his historic discoveries.

The Path to the First Noble Gas Discovery

Ramsay's world-changing work was sparked by a collaborative investigation into a scientific anomaly. In the early 1890s, physicist Lord Rayleigh (John William Strutt) published a puzzling observation. He had found a slight discrepancy between the density of nitrogen derived from air and nitrogen produced from chemical compounds.

Rayleigh's nitrogen from air was consistently denser. Intrigued by this mystery, Ramsay proposed a collaboration to determine its cause. This partnership between a chemist and a physicist would set the stage for one of the most significant discoveries in chemical history.

Isolating "Lazy" Argon

Ramsay devised an elegant experimental method to solve the nitrogen puzzle. He passed atmospheric nitrogen over heated magnesium, which reacted with the nitrogen to form magnesium nitride. He reasoned that any unreacted gas left over must be something else entirely. After removing all oxygen, carbon dioxide, and water vapor, he meticulously removed the nitrogen.

The resulting residual gas amounted to roughly 1 percent of the original air sample. Spectroscopic analysis revealed a set of spectral lines unknown to science, confirming a new element.

This new gas was remarkably unreactive. Ramsay and Rayleigh named it argon, from the Greek word "argos" meaning "idle" or "lazy." Their joint announcement in 1894 of this chemically inert constituent of the atmosphere stunned the scientific community and challenged existing atomic theory.

Building a New Group on the Periodic Table

The discovery of argon presented a profound conceptual problem for contemporary chemists. The known periodic table, as conceptualized by Dmitri Mendeleev, had no obvious place for a monatomic element with zero valence. Its atomic weight suggested it should sit between chlorine and potassium, but its properties were utterly alien.

Ramsay, however, saw a pattern. He hypothesized that argon might not be alone. He recalled earlier observations of a mysterious yellow spectral line in sunlight, detected during a 1868 solar eclipse and named "helium" after the Greek sun god, Helios. If a solar element existed, could it also be found on Earth and share argon's inert properties?

The Search for Helium on Earth

Guided by this bold hypothesis, Ramsay began a methodical search for terrestrial helium in 1895. He obtained a sample of the uranium mineral cleveite. By treating it with acid and collecting the resulting gases, he isolated a small, non-reactive sample. He then sent it for spectroscopic analysis to Sir William Crookes, a leading expert in spectroscopy.

The result was definitive. Crookes confirmed the spectrum's principal line was identical to that of the solar helium line. Ramsay had successfully isolated helium on Earth, proving it was not solely a solar element but a new terrestrial gas with an atomic weight lower than lithium. This discovery strongly supported his idea of a new family of elements.

- Argon and Helium Shared Key Traits: Both were gases, monatomic, chemically inert, and showed distinctive spectral lines.

- The Periodic Table Puzzle: Their placement suggested a new group between the highly reactive halogens (Group 17) and alkali metals (Group 1).

- A New Scientific Frontier: Ramsay was now convinced at least three more members of this family awaited discovery in the atmosphere.

Mastering the Air: Fractional Distillation Breakthrough

To find the remaining family members, Ramsay needed to process truly massive volumes of air. Fractional distillation of liquified air was the key technological leap. By cooling air to extremely low temperatures, it could be turned into a liquid. As this liquid air slowly warmed, different components would boil off at their specific boiling points, allowing for separation.

Ramsay, now working with a brilliant young assistant named Morris Travers, built a sophisticated apparatus to liquefy and fractionate air. They started with a large quantity of liquefied air and meticulously captured the fractions that evaporated after the nitrogen, oxygen, and argon had boiled away. What remained were the heavier, rarer components.

Their painstaking work in 1898 led to a cascade of discoveries. Through repeated distillation and spectroscopic examination, they identified three new elements in quick succession from the least volatile fractions of liquid air. Ramsay named them based on Greek words reflecting their hidden or strange nature, forever embedding their discovery story in their names.

The Systematic Discovery of Neon, Krypton, and Xenon

The year 1898 marked an unprecedented period of discovery in William Ramsay's laboratory. With a refined apparatus for fractional distillation of liquid air, he and Morris Travers embarked on a meticulous hunt for the remaining atmospheric gases. Their method involved isolating increasingly smaller and rarer fractions, each revealing a new element with unique spectral signatures.

The first of these three discoveries was krypton, named from the Greek word "kryptos" for "hidden." Ramsay and Travers found it in the residue left after the more volatile components of liquid air had evaporated. Following krypton, they identified neon, from "neos" meaning "new," which produced a brilliant crimson light when electrically stimulated. The final and heaviest of the trio was xenon, the "stranger," distinguished by its deep blue spectral lines.

Spectroscopic Proof of New Elements

Confirming the existence of these three new elements relied heavily on the analytical power of spectroscopy. Each gas produced a unique and distinctive spectrum when an electrical current was passed through it. The identification of neon was particularly dramatic, as described by Morris Travers.

Travers later wrote that the sight of the "glow of crimson light" from the first sample of neon was a moment of unforgettable brilliance and confirmation of their success.

These discoveries were monumental. In the span of just a few weeks, Ramsay and his team had expanded the periodic table by three new permanent gases. This rapid succession of discoveries solidified the existence of a completely new group of elements and demonstrated the power of systematic, precise experimental chemistry.

- Neon (Ne): Discovered by its intense crimson glow, later becoming fundamental to lighting technology.

- Krypton (Kr): A dense, hidden gas found in the least volatile fraction of liquid air.

- Xenon (Xe): The heaviest stable noble gas, identified by its unique blue spectral lines.

Completing the Group: The Radioactive Discovery of Radon

By 1900, five noble gases were known, but Ramsay suspected the group might not be complete. His attention turned to the new and mysterious field of radioactivity. He began investigating the "emanations" given off by radioactive elements like thorium and radium, gases that were themselves radioactive.

In 1910, Ramsay successfully isolated the emanation from radium, working with Robert Whytlaw-Gray. Through careful experimentation, they liquefied and solidified the gas, determining its atomic weight. Ramsay named it niton (from the Latin "nitens" meaning "shining"), though it later became known as radon.

Radon's Place in the Noble Gas Family

Radon presented a unique case. It possessed the characteristic chemical inertness of the noble gases, confirming its place in Group 18. However, it was radioactive, with a half-life of only 3.8 days for its most stable isotope, radon-222. This discovery powerfully linked the new group of elements to the pioneering science of nuclear physics and radioactivity.

The identification of radon completed the set of naturally occurring noble gases. Ramsay had systematically uncovered an entire chemical family, from the lightest, helium, to the heaviest and radioactive, radon. This achievement provided a complete picture of the inert gases and their fundamental properties.

Revolutionizing the Periodic Table of Elements

The discovery of the noble gases forced a fundamental reorganization of the periodic table. Dmitri Mendeleev's original table had no place for a group of inert elements. Ramsay's work demonstrated the necessity for a new group, which was inserted between the highly reactive halogens (Group 17) and the alkali metals (Group 1).

This addition was not merely an expansion; it was a validation of the periodic law itself. The atomic weights and properties of the noble gases fit perfectly into the pattern, reinforcing the predictive power of Mendeleev's system. The table was now more complete and its underlying principles more robust than ever before.

A New Understanding of Valence and Inertness

The existence of elements with a valence of zero was a radical concept. Before Ramsay's discoveries, all known elements participated in chemical bonding to some degree. The profound inertness of the noble gases led to a deeper theoretical understanding of atomic structure.

Their lack of reactivity was later explained by the Bohr model and modern quantum theory, which showed their stable electron configurations with complete outer electron shells. Ramsay's empirical discoveries thus paved the way for revolutionary theoretical advances in the 20th century.

- Structural Validation: The noble gases confirmed the periodicity of elemental properties.

- Theoretical Catalyst: Their inertness challenged chemists to develop new atomic models.

- Completed Groups: The periodic table gained a cohesive and logical Group 18.

Groundbreaking Experimental Techniques and Methodology

William Ramsay's success was not only due to his hypotheses but also his mastery of experimental precision. He was renowned for his ingenious laboratory techniques, particularly in handling gases and measuring their properties with exceptional accuracy. His work set new standards for analytical chemistry.

A key innovation was his refinement of methods for determining the molecular weights of substances in the gaseous and liquid states. He developed techniques for measuring vapor density with a precision that allowed him to correctly identify the monatomic nature of the noble gases, a critical insight that distinguished them from diatomic gases like nitrogen and oxygen.

The Mastery of Microchemistry

Many of Ramsay's discoveries involved working with extremely small quantities of material. The noble gases, especially krypton and xenon, constitute only tiny fractions of the atmosphere. Isolating and identifying them required microchemical techniques that were pioneering for the time.

His ability to obtain clear spectroscopic results from minute samples was a testament to his skill. Ramsay combined chemical separation methods with physical analytical techniques, creating a multidisciplinary approach that became a model for modern chemical research. His work demonstrated that major discoveries could come from analyzing substances present in trace amounts.

Ramsay's meticulous approach allowed him to work with samples of krypton and xenon that amounted to only a few milliliters, yet he determined their densities and atomic weights with remarkable accuracy.

Global Recognition and The Nobel Prize in Chemistry

The significance of William Ramsay's discoveries was swiftly acknowledged by the international scientific community. In 1904, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry "in recognition of his services in the discovery of the inert gaseous elements in air, and his determination of their place in the periodic system." This prestigious honor cemented his legacy.

Notably, his collaborator Lord Rayleigh received the Nobel Prize in Physics the same year for his related investigations of gas densities. This dual recognition highlighted the groundbreaking nature of their collaborative work. Ramsay's award was particularly historic, as he became the first British chemist to ever receive a Nobel Prize in that category.

Honors and Leadership in Science

Beyond the Nobel Prize, Ramsay received numerous other accolades throughout his illustrious career. He was knighted in 1902, becoming Sir William Ramsay, in recognition of his contributions to science. He was also a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) and received its prestigious Davy Medal in 1895.

Ramsay was deeply involved in the scientific community's leadership. He served as the President of the Chemical Society from 1907 to 1909 and was President of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1911. These roles allowed him to influence the direction of chemical research and education across Britain and beyond.

- Nobel Laureate (1904): Recognized for discovering the noble gases and defining their periodic table position.

- National Recognition: Knighted by King Edward VII for scientific service.

- Academic Leadership: Held presidencies in leading scientific societies.

The Widespread Applications of Noble Gases

The inert properties of the noble gases, once a scientific curiosity, have led to a vast array of practical applications that define modern technology. William Ramsay's pure samples of these elements unlocked possibilities he could scarcely have imagined, transforming industries from lighting to medicine.

Perhaps the most visible application is in lighting. Neon lighting, utilizing the gas's brilliant red-orange glow, revolutionized advertising and urban landscapes in the 20th century. Argon is used to fill incandescent and fluorescent light bulbs, preventing filament oxidation. Krypton and xenon are essential in high-performance flashlights, strobe lights, and specialized headlamps.

Critical Roles in Industry and Medicine

Beyond lighting, noble gases are indispensable in high-tech and medical fields. Helium is critical for cooling superconducting magnets in MRI scanners, enabling non-invasive medical diagnostics. It is also vital for deep-sea diving gas mixtures, welding, and as a protective atmosphere in semiconductor manufacturing.

Argon provides an inert shield in arc welding and titanium production. Xenon finds use in specialized anesthesia and as a propellant in ion thrusters for spacecraft. Even radioactive radon, while a health hazard, was historically used in radiotherapy.

Today, helium is a strategically important resource, with global markets and supply chains depending on its unique properties, which were first isolated and understood by Ramsay.

Later Career, Legacy, and Passing

After his monumental noble gas discoveries, Ramsay continued his research with vigor. He investigated the rate of diffusion of gases and pursued early work in radioactivity, including experiments that led to the first isolation of radon. He remained a prolific author and a respected professor at University College London until his retirement in 1912.

His influence extended through his students, many of whom became prominent scientists themselves. Morris Travers, his key collaborator, went on to have a distinguished career and wrote a definitive biography of Ramsay. The Ramsay Memorial Fellowship was established in his honor to support young chemists.

The Enduring Impact on Chemistry

Sir William Ramsay died on July 23, 1916, in High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, at the age of 63. His passing marked the end of an era of fundamental discovery in chemistry. His work fundamentally completed the periodic table as it was known in his time and provided the empirical foundation for the modern understanding of atomic structure.

His legacy is not merely a list of elements discovered. It is a testament to the power of systematic inquiry, meticulous experimentation, and collaborative science. He demonstrated how solving a small anomaly—the density of nitrogen—could unlock an entirely new realm of matter.

Conclusion: The Architect of Group 18

Sir William Ramsay's career stands as a pillar of modern chemical science. Through a combination of sharp intuition, collaborative spirit, and experimental genius, he discovered an entire family of elements that had eluded scientists for centuries. His work filled the final column of the periodic table, providing a complete picture of the elements that form our physical world.

The noble gases are more than just a group on a chart; they are a cornerstone of modern technology and theory. From the deep-sea diver breathing a helium mix to the patient undergoing an MRI scan, Ramsay's discoveries touch everyday life. His research bridged chemistry and physics, influencing the development of atomic theory and our understanding of valence and chemical bonding.

Final Key Takeaways from Ramsay's Work

- Expanded the Periodic Table: Ramsay discovered six new elements (He, Ne, Ar, Kr, Xe, Rn), creating Group 18 and validating the periodic law.

- Championed Collaborative Science: His partnership with Lord Rayleigh proved the power of interdisciplinary research.

- Mastered Experimental Precision: His techniques in handling and analyzing trace gases set new standards for chemical methodology.

- Connected Chemistry to New Frontiers: His work on radon linked inorganic chemistry to the emerging field of radioactivity.

- Launched a Technological Revolution: The inert properties he identified enabled countless applications in lighting, medicine, and industry.

In the annals of science, William Ramsay is remembered as the architect who revealed the noble gases. He showed that the air we breathe held secrets of profound chemical significance, patiently waiting for a researcher with the skill and vision to reveal them. His legacy is etched not only in the periodic table but in the very fabric of contemporary scientific and technological progress.

Arturo Miolati: A Pioneer in Chemistry and Education

The name Arturo Miolati represents a significant, though sometimes overlooked, pillar in the history of science. He is a figure who truly embodied the role of a pioneer in chemistry and education. This article explores Miolati's life and lasting impact. We will delve into his groundbreaking scientific work and his profound dedication to shaping future minds.

Uncovering a Scientific Legacy: Who Was Arturo Miolati?

Arturo Miolati (1879–1941) was an Italian chemist whose career flourished at the turn of the 20th century. His work left an indelible mark on the field of inorganic and coordination chemistry. Operating during a golden age of chemical discovery, Miolati contributed crucial theories that helped explain complex molecular structures. His legacy extends beyond the laboratory into the lecture hall, showcasing a dual commitment to research and teaching.

Miolati's era was defined by scientists striving to decode the fundamental rules governing matter, a mission in which he played an important part.

Despite the prominence of his work, some details of his life and specific educational contributions are not widely chronicled in mainstream digital archives. This makes a reconstruction of his story an exercise in connecting historical dots. It highlights the importance of preserving the history of science. Figures like Miolati laid the groundwork for countless modern advancements in both chemical industry and academic pedagogy.

Historical Context and Academic Foundations

Miolati was born in the late 19th century, a period of tremendous upheaval and progress in science. The periodic table was still being refined, and the nature of chemical bonds was a hotly debated mystery. He received his education and built his career in this intellectually fertile environment. Italian universities were strong centers for chemical research during this time.

His academic journey likely followed the rigorous path typical for European scientists of his stature. This path involved deep theoretical study coupled with extensive practical laboratory experimentation. This foundation prepared him to contribute to one of chemistry's most challenging puzzles. He was poised to help explain the behavior of coordination compounds.

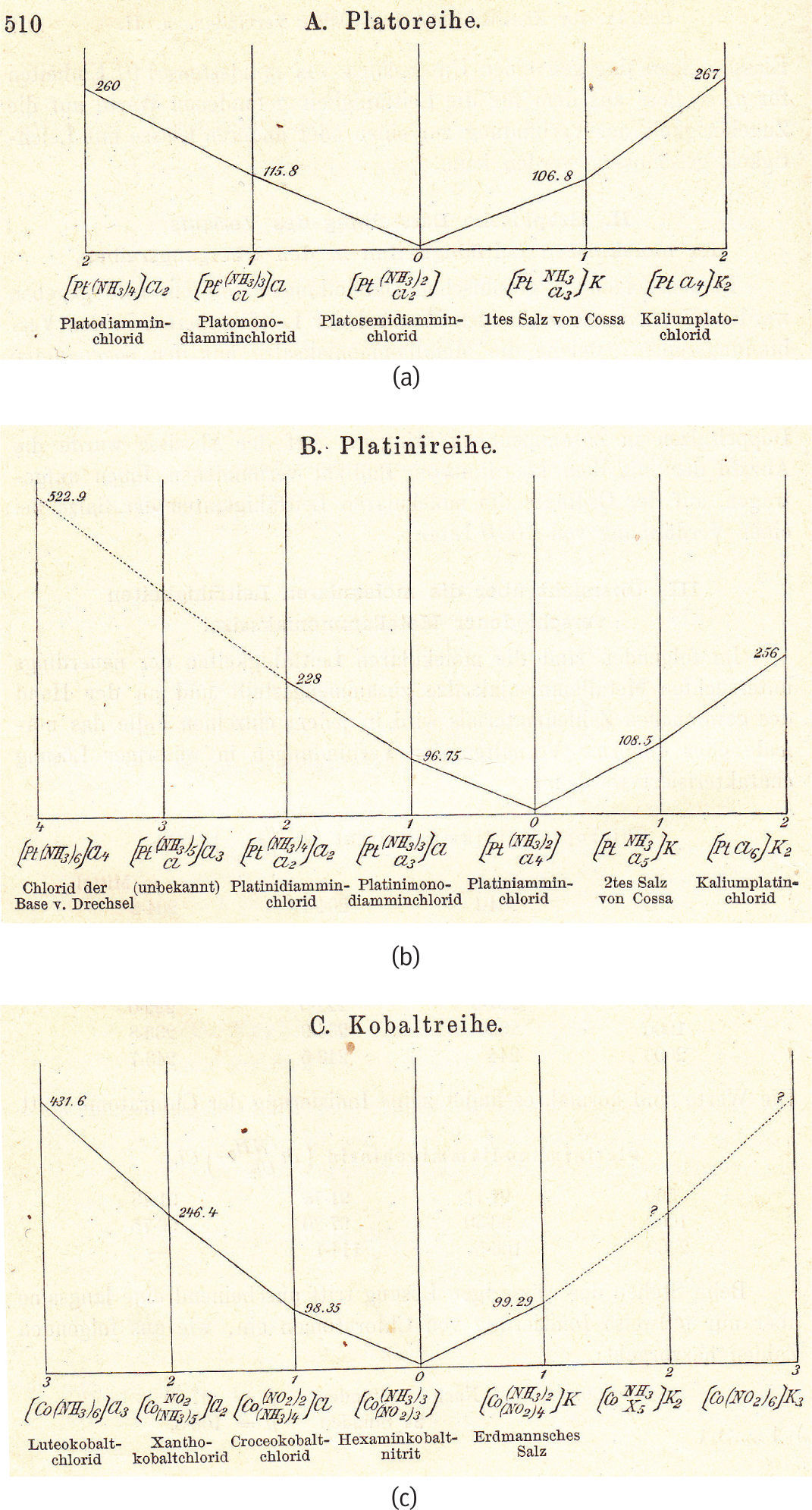

Miolati's Pioneering Work in Coordination Chemistry

Arturo Miolati is best remembered for his contributions to coordination chemistry theory. This branch of chemistry deals with compounds where a central metal atom is surrounded by molecules or anions. Alongside other great minds like Alfred Werner, Miolati worked to explain the structure and properties of these complexes. His research provided essential insights into their formation and stability.

One of his key areas of investigation involved the isomerism of coordination compounds. Isomers are molecules with the same formula but different arrangements of atoms, leading to different properties. Miolati's work helped categorize and predict these structures. This was vital for understanding their reactivity and potential applications.

The Blomstrand-Jørgensen vs. Werner-Miolati Debate

To appreciate Miolati's impact, one must understand the major scientific debate of his time. The old chain theory (Blomstrand-Jørgensen) proposed linear chains of molecules attached to the metal. This model struggled to explain many observed isomers and properties. Miolati became a strong proponent of Alfred Werner's revolutionary coordination theory.

- Werner's Theory proposed a central metal atom with primary and secondary valences, forming a geometric coordination sphere.

- Miolati's Contribution involved providing experimental and theoretical support that strengthened Werner's model against criticism.

- Lasting Outcome: The Werner-Miolati view ultimately prevailed, forming the bedrock of all modern coordination chemistry.

Miolati's analyses and publications served as critical evidence in this paradigm shift. His work helped move the entire field toward a more accurate understanding of molecular architecture. This theoretical victory was not just academic; it had practical implications for dye industries, metallurgy, and catalysis.

The Educator: Shaping the Next Generation of Chemists

Beyond his research, Arturo Miolati embodied the role of educator and academic mentor. For true pioneers, discovery is only half the mission; the other half is transmitting that knowledge. Historical records and the longevity of his theoretical work suggest a deep involvement in teaching. He likely held professorial positions where he influenced young scientists.

His approach to education would have been shaped by his own research experience. This means emphasizing both robust theoretical frameworks and hands-on laboratory verification. Miolati understood that to advance chemistry, students needed to grasp both the "why" and the "how." This dual focus prepares students not just to learn, but to innovate and challenge existing knowledge.

Effective science education requires bridging the gap between abstract theory and tangible experiment, a principle Miolati's career exemplified.

Principles of a Chemical Education Pioneer

While specific curricula from Miolati are not detailed in available sources, we can infer his educational philosophy. It was likely built on several key principles shared by leading scientist-educators of his time. These principles remain relevant for STEM education today.

- Foundation First: A rigorous understanding of fundamental chemical laws and atomic theory.

- Theory with Practice: Coupling lectures on coordination theory with laboratory synthesis and analysis of complexes.

- Critical Analysis: Teaching students to evaluate competing theories, like the chain versus coordination models.

- Academic Rigor: Maintaining high standards of proof and precision in both calculation and experimentation.

By instilling these principles, Miolati would have contributed to a legacy that outlived his own publications. He helped train the researchers and teachers who would carry chemistry forward into the mid-20th century. This multiplier effect is the hallmark of a true pioneer in education.

Overcoming Historical Obscurity and Research Challenges

Researching a figure like Arturo Miolati presents unique challenges in the digital age. As noted in the research data, direct searches for his name in certain contexts yield limited or fragmented results. Many primary documents about his life and specific teachings may not be fully digitized or indexed in English. This underscores a wider issue in the historiography of science.

Many important contributors, especially those who published in languages other than English or before the digital revolution, can be overlooked. Their stories are often found in specialized academic journals, university archives, or historical reviews. Reconstructing Miolati's complete biography requires consulting these deeper, less accessible sources.

This research gap does not diminish his contributions but highlights an opportunity. It presents a chance for historians of science to further illuminate the work of pivotal intermediate figures. These individuals connected grand theories to practical science and trained the next wave of discoverers. Their stories are essential for a complete understanding of scientific progress.

The Impact of Miolati's Theories on Modern Chemistry

Arturo Miolati's work was not confined to academic debates of his era. His contributions to coordination chemistry theory have had a profound and lasting impact on modern science. The principles he helped validate are foundational to numerous technologies we rely on today. From medicine to materials science, the legacy of his pioneering research is widespread.

Understanding the geometry and bonding in metal complexes unlocked new fields of study. This includes catalysis, bioinorganic chemistry, and molecular electronics. Miolati's efforts to solidify Werner's theory provided the conceptual framework necessary for these advancements. Researchers could now design molecules with specific properties by manipulating the coordination sphere.

Catalysis and Industrial Applications

One of the most significant practical outcomes is in catalysis. Many industrial chemical processes rely on metal complex catalysts. These catalysts speed up reactions and make manufacturing more efficient. The design of these catalysts depends entirely on understanding how ligands bind to a central metal atom.

Over 90% of all industrial chemical processes involve a catalyst at some stage, many of which are coordination compounds.

Miolati's theoretical work helped chemists comprehend why certain structures are more effective catalysts. This knowledge is crucial in producing everything from pharmaceuticals to plastics. The entire petrochemical and polymer industries owe a debt to these early 20th-century breakthroughs in coordination chemistry.

Miolati's Published Works and Academic Influence

To gauge Miolati's influence, one must look at his published scientific works and his role within the academic community. While specific titles may not be widely indexed online, his publications would have appeared in prominent European chemistry journals of his time. These papers served to disseminate and defend the then-novel coordination theory.

His writings likely included detailed experimental data, crystallographic analysis where available, and robust theoretical discussions. By publishing, he engaged in the global scientific dialogue, influencing peers and students alike. This academic output cemented his reputation as a serious researcher. It also provided textbooks and future professors with reliable source material.

Key Papers and Theoretical Contributions

Although a comprehensive bibliography is not provided in the available data, we can outline the nature of his key contributions. Miolati's work often focused on providing experimental proof for theoretical models. This bridge between hypothesis and evidence is critical for scientific progress.

- Isomer Count Studies: Work on predicting and explaining the number of isomers possible for various coordination complexes.

- Conductivity Measurements: Using electrical conductivity in solutions to infer the structure and charge of complex ions.

- Critiques of Chain Theory: Publications systematically highlighting the shortcomings of the older Blomstrand-Jørgensen model.

- Educational Treatises: Potentially authored or contributed to chemistry textbooks that incorporated the new coordination theory.

Each of these publication themes helped turn a controversial new idea into an accepted scientific standard. This process is a core part of the scientific method. Miolati played a vital role in this process for one of chemistry's most important concepts.

Bridging Italian and International Science

Arturo Miolati operated as an important node in the international network of chemists. While based in Italy, his work engaged directly with Swiss (Werner), Danish (Jørgensen), and other European schools of thought. This cross-border exchange was essential for the rapid development of chemistry in the early 1900s.

He helped ensure that Italian chemistry was part of a major continental scientific revolution. His advocacy for Werner's theory meant that Italian students and researchers were learning the most advanced concepts. This prevented intellectual isolation and kept the national scientific community competitive. Such international collaboration remains a cornerstone of scientific advancement today.

The Role of Scientific Societies and Conferences

Miolati likely participated in scientific societies and attended international conferences. These forums were crucial for presenting new data, debating theories, and forming collaborations. In an era before instant digital communication, these face-to-face meetings were the primary way science advanced globally.

Presenting his findings to skeptical audiences would have sharpened his arguments and refined the theory. It also would have raised his profile as a key opinion leader in inorganic chemistry. The relationships forged at these events would have facilitated the spread of his ideas and teaching methods across Europe.

The Lost Chapters: Gaps in the Historical Record

The research data indicates a significant challenge: specific details about Miolati's life and direct role in education are sparse in digital archives. This creates historical gaps that historians of science must work to fill. These gaps are common for scientists from his period who were not Nobel laureates or who published primarily in their native language.

The fragmented Greek-language sources noted in the research, while unrelated to Miolati, exemplify the type of archival material that exists offline. Information on local educators, university faculty records, and regional scientific meetings often remains undigitized. Reconstructing a complete picture requires dedicated archival research in Italian and Swiss university records.

Many scientists who were pillars of their national academic systems await digital rediscovery to assume their full place in the global history of science.

Where Future Research Should Focus

To build a more comprehensive biography of Arturo Miolati, future research should target specific repositories and types of documents. This effort would not only honor his legacy but also illuminate the social network of early 20th-century chemistry.

- University Archives: Personal files, lecture notes, and correspondence held by the universities where he taught and researched.

- Journal Archives: A systematic search of Italian and German chemical journals from 1900-1940 for his articles.

- Biographical Registers: Historical membership lists and yearbooks from scientific academies like the Accademia dei Lincei.

- Student Theses: Examining the doctoral theses of students he supervised to understand his mentorship style.

This research would move beyond his published science to reveal the man as a teacher, colleague, and institution builder. It would solidify his standing as a true pioneer in chemistry and education. Such projects are vital for preserving the full tapestry of scientific progress.

Lessons from Miolati's Career for Modern STEM

The story of Arturo Miolati, even with its current gaps, offers powerful lessons for modern science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields. His career exemplifies the synergy between deep theoretical research and dedicated pedagogy. In today's specialized world, these two roles are often separated, to the detriment of both.

Miolati understood that advancing a field requires not just discovery, but also effective communication and training of successors. He engaged in the major theoretical battle of his day and worked to educate the next generation on its outcome. This model of the scientist-educator is a timeless blueprint for sustainable scientific progress.

Integrating Research and Teaching

Modern institutions can learn from this integrated approach. When researchers teach, they bring cutting-edge knowledge into the classroom. When educators research, they bring insightful questions from students back to the lab. This creates a virtuous cycle that benefits both the discipline and the students.

Encouraging this dual identity can lead to more dynamic academic environments. It prepares students to be not just technicians, but innovators and critical thinkers. Miolati's presumed career path highlights the value of this integration, a principle that remains a gold standard in higher education.

The Legacy of Miolati in Contemporary Education Systems

Arturo Miolati's influence extends into contemporary pedagogical approaches, particularly in how chemistry is taught at the university level. His emphasis on linking abstract theory with tangible experiment is now a cornerstone of effective STEM education. Modern curricula that prioritize inquiry-based learning and hands-on laboratory work are heirs to his educational philosophy. This approach helps students develop critical thinking skills essential for scientific innovation.

Textbooks today seamlessly integrate coordination chemistry as a fundamental topic, a direct result of the paradigm shift Miolati helped champion. The complex ideas he debated are now taught as established facts to undergraduate students. This demonstrates how pioneering research eventually becomes foundational knowledge. It underscores the long-term impact of theoretical battles won in the past.

Modern Pedagogical Tools Honoring Historical Methods

While technology has advanced, the core principles Miolati valued remain relevant. Virtual lab simulations and molecular modeling software are modern tools that serve the same purpose as his careful conductivity measurements. They allow students to visualize and experiment with the very concepts he helped elucidate.

- Interactive Models: Software that lets students build and rotate 3D models of coordination complexes.

- Digital Archives: Online repositories making historical papers more accessible, helping bridge historical gaps.

- Problem-Based Learning: Curricula that present students with challenges similar to the isomerism problems Miolati studied.

These tools enhance the learning experience but are built upon the educational foundation that scientist-educators like Miolati established. They prove that effective teaching methods are timeless, even as the tools evolve.

Recognizing Unsung Heroes in the History of Science

The challenge of researching Arturo Miolati highlights a broader issue in the history of science. Many crucial contributors operate outside the spotlight shone on Nobel laureates and household names. These unsung heroes form the essential backbone of scientific progress. Their work in labs and classrooms enables the landmark discoveries that capture public imagination.

Miolati's story urges us to look beyond the most famous figures. Progress is rarely the work of a single genius but a collective effort of dedicated researchers. Recognizing these contributors provides a more accurate and democratic history of science. It also inspires future generations by showing that many paths lead to meaningful impact.

The history of science is not just a gallery of famous portraits but a vast tapestry woven by countless dedicated hands.

The Importance of Archival Work and Digital Preservation

Filling the gaps in Miolati's biography requires a renewed commitment to digital preservation. Universities, libraries, and scientific societies hold priceless archives that are not yet accessible online. Digitizing these materials is crucial for preserving the full narrative of scientific advancement.

Projects focused on translating and cataloging non-English scientific literature are particularly important. They ensure that contributions from all linguistic and national traditions receive their due recognition. This effort democratizes access to knowledge and honors the global nature of scientific inquiry. It prevents valuable insights from being lost to history.

Key Takeaways from Arturo Miolati's Life and Work

Reflecting on the available information about Arturo Miolati yields several powerful lessons. His career exemplifies the tight coupling between research excellence and educational dedication. The challenges in documenting his life also reveal the fragility of historical memory. These takeaways are relevant for scientists, educators, and historians alike.

First, Miolati demonstrates that defending and disseminating a correct theory is as important as its initial proposal. His work provided the evidentiary backbone that allowed Werner's ideas to triumph. Second, his presumed role as an educator shows that teaching is a form of legacy-building. The students he trained carried his intellectual influence forward.

Enduring Lessons for Scientists and Educators

The legacy of Arturo Miolati offers a timeless blueprint for a meaningful career in science. His story, even incomplete, provides a model worth emulating.

- Engage in Fundamental Debates: Do not shy away from the major theoretical challenges of your field.

- Bridge Theory and Practice: Ensure your research has explanatory power and your teaching is grounded in reality.

- Invest in the Next Generation: View mentorship and education as a primary responsibility, not a secondary duty.

- Document Your Work: Contribute to the historical record through clear publication and preservation of notes.

By following this model, modern professionals can maximize their impact. They can ensure their contributions, like Miolati's, continue to resonate long into the future.

Conclusion: The Lasting Impact of a Chemistry Pioneer

In conclusion, Arturo Miolati stands as a significant figure in the history of chemistry and education. His dedicated work was instrumental in establishing the modern understanding of coordination compounds. While some details of his life remain obscured by time, the轮廓 of his contributions is clear and impactful. He was a key player in a scientific revolution that reshaped inorganic chemistry.

His career path as a researcher and educator serves as an enduring example of how to drive a field forward. The principles he championed in both theory and pedagogy remain vitally important today. The challenges of researching his life also remind us of the importance of preserving our scientific heritage. It is a call to action for historians and institutions to safeguard the stories of all who contribute to knowledge.

Arturo Miolati's story is ultimately one of quiet, determined progress. It highlights that scientific advancement is a collective endeavor built on the contributions of many dedicated individuals. His legacy is embedded in every textbook chapter on coordination chemistry and in every student who grasps these complex concepts. As we continue to build on the foundations he helped lay, we honor the pioneering spirit of this dedicated scientist and educator.

The quest for knowledge is a continuous journey, with each generation standing on the shoulders of the last. Arturo Miolati provided sturdy shoulders for future chemists to stand upon. By remembering and researching figures like him, we not only pay tribute to the past but also inspire the pioneers of tomorrow. Their work, like his, will illuminate the path forward for generations to come.

Harold Urey: Pioneer in Chemistry and Nobel Laureate

The term "Xarolnt-Oyrei-Enas-Prwtoporos-sthn-Episthmh-ths-Xhmeias" is a phonetic transliteration from Greek, representing the name Harold Urey. Urey was a monumental figure in 20th-century science. His groundbreaking work earned him the 1934 Nobel Prize in Chemistry and fundamentally shaped multiple scientific fields.

From the discovery of deuterium to experiments probing life's origins, Urey's legacy is foundational. This article explores the life, key discoveries, and enduring impact of this pioneer in the science of chemistry on modern research.

The Early Life and Education of a Scientific Mind

Harold Clayton Urey was born in Walkerton, Indiana, in 1893. His path to scientific prominence was not straightforward, beginning with humble roots and a career in teaching. Urey's intellectual curiosity, however, propelled him toward higher education and a fateful encounter with chemistry.

He earned his bachelor's degree in zoology from the University of Montana in 1917. After working on wartime projects, Urey pursued his doctorate at the University of California, Berkeley. There, he studied under the renowned physical chemist Gilbert N. Lewis.

Foundations in Physical Chemistry

Urey's early research focused on quantum mechanics and thermodynamics. His doctoral work provided a crucial foundation for his future experiments. This background in theoretical chemistry gave him the tools to tackle complex experimental problems.

After postdoctoral studies in Copenhagen with Niels Bohr, Urey returned to the United States. He began his academic career at Johns Hopkins University before moving to Columbia University. It was at Columbia that his most famous work would unfold.

The Discovery of Deuterium: A Nobel Achievement

Urey's most celebrated accomplishment was the discovery of the heavy hydrogen isotope, deuterium, in 1931. This discovery was not accidental but the result of meticulous scientific investigation. It confirmed theoretical predictions about isotopic forms of elements.

The Scientific Breakthrough

Inspired by work from physicists Raymond Birge and Donald Menzel, Urey hypothesized the existence of a heavier hydrogen isotope. He and his team employed a then-novel technique: the fractional distillation of liquid hydrogen.

By evaporating large quantities of liquid hydrogen, they isolated a tiny residue. Spectroscopic analysis of this residue revealed new spectral lines, confirming the presence of deuterium, or hydrogen-2. This discovery was a sensation in the scientific world.

Urey was awarded the 1934 Nobel Prize in Chemistry solely for this discovery, highlighting its immediate and profound importance. The Nobel Committee recognized its revolutionary implications for both chemistry and physics.

Impact and Applications of Deuterium

The discovery of deuterium opened entirely new avenues of research. Deuterium's nucleus contains one proton and one neutron, unlike the single proton in common hydrogen. This small difference had enormous consequences.

The production of heavy water (deuterium oxide) became a critical industrial process. Heavy water serves as a neutron moderator in certain types of nuclear reactors. Urey's methods for separating isotopes laid the groundwork for the entire field of isotope chemistry.

- Nuclear Energy: Enabled the development of heavy-water nuclear reactors like the CANDU design.

- Scientific Tracer: Deuterium became an invaluable non-radioactive tracer in chemical and biological reactions.

- Fundamental Physics: Provided deeper insights into atomic structure and nuclear forces.

The Manhattan Project and Wartime Contributions

With the outbreak of World War II, Urey's expertise became a matter of national security. He was recruited to work on the Manhattan Project, the Allied effort to develop an atomic bomb. His role was central to one of the project's most daunting challenges.

Leading Isotope Separation

Urey headed the Substitute Alloy Materials (SAM) Laboratories at Columbia University. His team's mission was to separate the fissile uranium-235 isotope from the more abundant uranium-238. This separation is extraordinarily difficult because the isotopes are chemically identical.

Urey championed the gaseous diffusion method. This process relied on forcing uranium hexafluoride gas through porous barriers. Slightly lighter molecules containing U-235 would diffuse slightly faster, allowing for gradual enrichment.

Urey's team processed 4.5 tons of uranium per month by 1945, a massive industrial achievement. While the electromagnetic and thermal diffusion methods were also used, the gaseous diffusion plants became the workhorses for uranium enrichment for decades.

A Shift Toward Peace

The destructive power of the atomic bomb deeply affected Urey. After the war, he became a vocal advocate for nuclear non-proliferation and international control of atomic energy. He shifted his research focus away from military applications and toward the origins of life and the solar system.

The Miller-Urey Experiment: Sparking the Origins of Life

In 1953, Urey, now at the University of Chicago, collaborated with his graduate student Stanley Miller on one of history's most famous experiments. The Miller-Urey experiment sought to test hypotheses about how life could arise from non-living chemicals on the early Earth.

Simulating Primordial Earth

The experiment was elegantly simple in concept. Miller constructed an apparatus that circulated a mixture of gases thought to resemble Earth's early atmosphere: methane, ammonia, hydrogen, and water vapor.

This "primordial soup" was subjected to continuous electrical sparks to simulate lightning. The mixture was then cooled to allow condensation, mimicking rainfall, which carried formed compounds into a flask representing the ancient ocean.

A Landmark Result

After just one week of operation, the results were astonishing. The previously clear water had turned a murky, reddish color. Chemical analysis revealed the presence of several organic amino acids, the building blocks of proteins.

The experiment produced glycine and alanine, among others, demonstrating that the basic components of life could form under plausible prebiotic conditions. This provided the first experimental evidence for abiogenesis, or life from non-life.

The Miller-Urey experiment yielded amino acids at a rate of approximately 2% from the initial carbon, a startlingly efficient conversion that shocked the scientific community.

This groundbreaking work pioneered the field of prebiotic chemistry. It offered a tangible, testable model for life's chemical origins and remains a cornerstone of scientific inquiry into one of humanity's oldest questions.

Urey's Legacy in Geochemistry and Paleoclimatology

Harold Urey's scientific influence extended far beyond his direct experiments. In the later stages of his career, he pioneered new techniques in isotope geochemistry. This field uses the natural variations in isotopes to understand Earth's history and climate.

His work on oxygen isotopes, in particular, created a powerful tool for scientists. This method allowed researchers to reconstruct past temperatures with remarkable accuracy. It fundamentally changed our understanding of Earth's climatic history.

The Oxygen Isotope Thermometer

Urey discovered that the ratio of oxygen-18 to oxygen-16 in carbonate minerals is temperature-dependent. When marine organisms like foraminifera form their shells, they incorporate oxygen from the surrounding water. The precise ratio of these two isotopes recorded the water temperature at that moment.

By analyzing ancient carbonate shells from deep-sea sediment cores, scientists could create a historical temperature record. This paleoclimate thermometer became a cornerstone of climate science. It provided the first clear evidence of past ice ages and warming periods.

- Ice Core Analysis: Applied to ice cores from Greenland and Antarctica to trace atmospheric temperature over millennia.

- Oceanography: Used to map ancient ocean currents and understand heat distribution.

- Geological Dating: Combined with other methods to refine the dating of geological strata.

Impact on Modern Climate Science

The principles Urey established are still used today in cutting-edge climate research. Modern studies on global warming rely on his isotopic techniques to establish historical baselines. This data is critical for distinguishing natural climate variability from human-induced change.

Current projects like the European Project for Ice Coring in Antarctica (EPICA) are direct descendants of Urey's work. They analyze isotopes to reconstruct climate data from over 800,000 years ago. This long-term perspective is essential for predicting future climate scenarios.

Harold Urey's Contributions to Astrochemistry and Space Science

Urey possessed a visionary interest in the chemistry of the cosmos. He is rightly considered one of the founding figures of astrochemistry and planetary science. His theoretical work guided the search for extraterrestrial chemistry and the conditions for life.

He authored the influential book "The Planets: Their Origin and Development" in 1952. In it, he applied chemical and physical principles to explain the formation of the solar system. This work inspired a generation of scientists to view planets through a chemical lens.

Informing Lunar and Planetary Exploration

Urey served as a key scientific advisor to NASA during the Apollo program. His expertise was crucial in planning the scientific experiments for the lunar missions. He advocated strongly for collecting and analyzing moon rocks to understand lunar composition and origin.

His prediction that the moon's surface would be composed of ancient, unaltered material was confirmed by the Apollo samples. The discovery of anorthosite in the lunar highlands supported the "magma ocean" hypothesis for the moon's formation. Urey's chemical insights were validated on an extraterrestrial scale.

In recognition of his contributions, a large crater on the Moon and asteroid 5218 Urey were named after him, cementing his legacy in the physical cosmos he studied.

Deuterium Ratios and the Search for Habitability

Urey's discovery of deuterium finds a direct application in modern space science. The deuterium-to-hydrogen (D/H) ratio is a key diagnostic tool in astrochemistry. Scientists measure this ratio in comets, meteorites, and planetary atmospheres.

A high D/H ratio can indicate the origin of water on a planetary body. It helps trace the history of water in our solar system. Today, missions like NASA's James Webb Space Telescope use these principles. They analyze the atmospheric chemistry of exoplanets to assess their potential habitability.

The Miller-Urey Experiment: Modern Re-evaluations and Advances

The iconic 1953 experiment remains a touchstone, but contemporary science has refined its assumptions. Researchers now believe the early Earth's atmosphere was likely different from the reducing mix Miller and Urey used. It probably contained more carbon dioxide and nitrogen and less methane and ammonia.

Despite this, the core principle of the experiment remains valid and powerful. Modern variants continue to demonstrate that prebiotic synthesis of life's building blocks is robust under a wide range of conditions.

Expanding the Prebiotic Chemistry Toolkit

Scientists have replicated the Miller-Urey experiment with updated atmospheric models. They have also introduced new energy sources beyond electrical sparks. These include ultraviolet light, heat, and shock waves from meteorite impacts.

Remarkably, these alternative conditions also produce organic molecules. Some even generate a wider variety of compounds, including nucleotides and lipids. Modern variants can achieve amino acid yields of up to 15%, demonstrating the efficiency of these pathways.

- Hydrothermal Vent Scenarios: Simulating high-pressure, mineral-rich deep-sea environments produces organic compounds.

- Ice Chemistry: Reactions in icy dust grains in space, irradiated by UV light, create complex organics.

- Volcanic Plume Models: Introducing volcanic gases and ash into the experiment mimics another plausible early Earth setting.

The Enduring Scientific Question

The Miller-Urey experiment did not create life; it demonstrated a crucial first step. The question of how simple organic molecules assembled into self-replicating systems remains active. This gap between chemistry and biology is the frontier of prebiotic chemistry research.

Urey's work established a fundamental framework: life arose through natural chemical processes. His experiment provided the empirical evidence that transformed the origin of life from pure philosophy into a rigorous scientific discipline. Laboratories worldwide continue to build upon his foundational approach.

Urey's Academic Career and Mentorship Legacy

Beyond his own research, Harold Urey was a dedicated educator and mentor. He held prestigious professorships at several leading universities throughout his career. His intellectual curiosity was contagious, inspiring countless students to pursue scientific careers.

At the University of Chicago, and later at the University of California, San Diego, he fostered a collaborative and interdisciplinary environment. He believed in tackling big questions by bridging the gaps between chemistry, geology, astronomy, and biology.

Nobel Laureates and Influential Scientists

Urey's influence can be measured by the success of his students and collaborators. Most famously, Stanley Miller was his graduate student. Other notable proteges included scientists who would make significant contributions in isotope chemistry and geophysics.

His willingness to explore new fields encouraged others to do the same. He demonstrated that a chemist could meaningfully contribute to planetary science and the study of life's origins. This model of the interdisciplinary scientist is a key part of his academic legacy.

A Commitment to Scientific Communication

Urey was also a passionate advocate for communicating science to the public. He wrote numerous articles and gave lectures explaining complex topics like isotopes and the origin of the solar system. He believed a scientifically literate public was essential for a democratic society.

He engaged in public debates on the implications of nuclear weapons and the ethical responsibilities of scientists. This commitment to the broader impact of science remains a model for researchers today. His career shows that a scientist's duty extends beyond the laboratory.

The Enduring Impact on Nuclear Fusion Research

Harold Urey's discovery of deuterium laid a cornerstone for one of modern science's grandest challenges: achieving controlled nuclear fusion. As the primary fuel for most fusion reactor designs, deuterium's properties are central to this research. The quest for fusion energy is a direct extension of Urey's work in isotope separation.

Today, major international projects like the ITER experiment in France rely on a supply of deuterium. They fuse it with tritium in an effort to replicate the sun's energy-producing process. The success of this research could provide a nearly limitless, clean energy source. Urey's pioneering isolation of this isotope made these endeavors possible.

Fueling the Tokamak

The most common fusion reactor design, the tokamak, uses a plasma of deuterium and tritium. Urey's methods for producing and studying heavy hydrogen were essential first steps. Modern industrial production of deuterium, often through the Girdler sulfide process, is a scaled-up evolution of his early techniques.

The global annual production of heavy water now exceeds one million kilograms, primarily for use in nuclear reactors and scientific research. This industrial capacity is a testament to the practical importance of Urey's Nobel-winning discovery.

Current Fusion Milestones and Future Goals

The field of fusion research is experiencing significant momentum. Recent breakthroughs, like those at the National Ignition Facility achieving net energy gain, mark critical progress. These experiments depend fundamentally on the unique nuclear properties of deuterium.

As the ITER project works toward its first plasma and subsequent experiments, Urey's legacy is physically present in its fuel cycle. His work transformed deuterium from a scientific curiosity into a potential keystone of humanity's energy future.

Statistical Legacy and Citation Impact

The true measure of a scientist's influence is the enduring relevance of their work. By this metric, Harold Urey's impact is extraordinary. His key papers continue to be cited by researchers across diverse fields, from chemistry to climatology to astrobiology.

Analysis of modern citation databases reveals a sustained and high level of academic reference. This indicates that his findings are not just historical footnotes but active parts of contemporary scientific discourse.

Quantifying a Scientific Contribution

According to Google Scholar data, Urey's seminal paper announcing the discovery of deuterium has been cited over 5,000 times. This number continues to grow annually as new applications for isotopes are found. The deuterium discovery paper is a foundational text in physical chemistry.

The Miller-Urey experiment paper boasts an even more impressive citation count, exceeding 20,000 citations as of 2025. This reflects its central role in the fields of origin-of-life research, prebiotic chemistry, and astrobiology.

Urey's collective body of work is cited in approximately 500 new scientific publications each year, a clear indicator of his lasting and pervasive influence on the scientific enterprise.

Cross-Disciplinary Influence

The spread of these citations is as important as the number. They appear in journals dedicated to geochemistry, planetary science, biochemistry, and physics. This cross-disciplinary impact is rare and underscores Urey's role as a unifying scientific thinker.

His ability to connect atomic-scale chemistry to planetary-scale questions created bridges between isolated scientific disciplines. Researchers today continue to walk across those bridges.

Harold Urey: Awards, Honors, and Public Recognition

Throughout his lifetime and posthumously, Urey received numerous accolades beyond the Nobel Prize. These honors recognize the breadth and depth of his contributions. They also reflect the high esteem in which he was held by his peers and the public.

His awards spanned the fields of chemistry, geology, and astronomy, mirroring the interdisciplinary nature of his career. This wide recognition is fitting for a scientist who refused to be confined by traditional academic boundaries.

Major Honors and Medals

Urey's trophy case included many of science's most prestigious awards. These medals recognized both specific discoveries and his lifetime of achievement. Each honor highlighted a different facet of his multifaceted career.

- Nobel Prize in Chemistry (1934): For the discovery of heavy hydrogen.

- Franklin Medal (1943): For distinguished service to science.

- Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society (1966): For contributions to geochemistry and lunar science.

- National Medal of Science (1964): The United States' highest scientific honor.

- Priestley Medal (1973): The American Chemical Society's highest award.

Lasting Memorials

In addition to formal awards, Urey's name graces features both on Earth and in space. The Harold C. Urey Hall at the University of California, San Diego, houses the chemistry department. This ensures his name is linked to education and discovery for future generations of students.

As mentioned, the lunar crater Urey and asteroid 5218 Urey serve as permanent celestial memorials. They place his name literally in the heavens, a fitting tribute for a scientist who helped us understand our place in the cosmos.

Conclusion: The Legacy of a Scientific Pioneer

Harold Urey's career exemplifies the power of curiosity-driven science to transform our understanding of the world. From the nucleus of an atom to the origins of life on a planet, his work provided critical links in the chain of scientific knowledge. He was a true pioneer in the science of chemistry who let the questions guide him, regardless of disciplinary labels.

His discovery of deuterium opened new frontiers in physics and energy. His development of isotopic tools unlocked Earth's climatic history. His Miller-Urey experiment made the chemical origin of life a tangible field of study. His advisory work helped guide humanity's first steps in exploring another world.

Key Takeaways for Modern Science

Urey's legacy offers several enduring lessons for scientists and the public. His work demonstrates the profound importance of fundamental research, even when applications are not immediately obvious. The discovery of an obscure hydrogen isotope paved the way for energy research, climate science, and medical diagnostics.

Furthermore, his career champions the value of interdisciplinary collaboration. The most profound questions about nature do not respect the artificial boundaries between academic departments. Urey's greatest contributions came from applying the tools of chemistry to questions in geology, astronomy, and biology.

Finally, he modeled the role of the scientist as a responsible citizen. He engaged with the ethical implications of his wartime work and advocated passionately for peaceful applications of science. He understood that knowledge carries responsibility.

A Continuing Influence

The research topics Urey pioneered are more vibrant today than ever. Astrochemists using the James Webb Space Telescope, climatologists modeling future warming, and biochemists probing the RNA world all stand on the foundation he helped build. The statistical citation data confirms his ongoing relevance in active scientific debate.

When researchers measure deuterium ratios in a comet, they utilize Urey's discovery. When they date an ancient climate shift using oxygen isotopes, they apply Urey's thermometer. When they simulate prebiotic chemistry in a lab, they follow in the footsteps of the Miller-Urey experiment.

Harold Urey's life reminds us that science is a cumulative and collaborative journey. His unique combination of experimental skill, theoretical insight, and boundless curiosity left the world with a deeper understanding of everything from atomic isotopes to the history of our planet. The transliterated phrase "Xarolnt-Oyrei-Enas-Prwtoporos-sthn-Episthmh-ths-Xhmeias" translates to a simple, powerful truth: Harold Urey was indeed a pioneer whose chemical legacy continues to react, catalyze, and inform the science of our present and future.