Lead Market Outlook: Trends, Demand, and Forecasts to 2032

The global lead market remains a cornerstone of modern industry, driven by its essential role in energy storage and industrial applications. With a history spanning over 5,000 years, this durable metal is primarily consumed in the production of lead-acid batteries. Current market analysis projects significant growth, with the sector expected to expand at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.9%, reaching approximately USD 38.57 billion by 2032.

Understanding Lead: A Durable Industrial Metal

Lead is a dense, blue-gray metal known for its high malleability and excellent corrosion resistance. It possesses a relatively low melting point, which makes it easy to cast and shape for a wide array of applications. These fundamental properties have made it a valuable material for centuries, from ancient Roman plumbing to modern technological solutions.

Key Physical and Chemical Properties

The metal's ductility and density are among its most valuable traits. It can be easily rolled into sheets or extruded into various forms without breaking. Furthermore, lead's resistance to corrosion by water and many acids ensures the longevity of products in which it is used, particularly in harsh environments.

Another critical property is its ability to effectively shield radiation. This makes it indispensable in medical settings for X-ray rooms and in nuclear power facilities. The combination of these characteristics solidifies lead's role as a versatile and reliable industrial material.

Primary Applications and Uses of Lead

The demand for lead is overwhelmingly dominated by a single application: lead-acid batteries. This sector accounts for more than 80% of global consumption. These batteries are crucial for starting, lighting, and ignition (SLI) systems in vehicles, as well as for energy storage in renewable systems and backup power supplies.

Beyond batteries, lead finds important uses in several other sectors. Its density makes it perfect for soundproofing and vibration damping in buildings. It is also used in roofing materials, ammunition, and, historically, in plumbing and paints, though these uses have declined due to health regulations.

Lead-Acid Batteries: The Dominant Driver

The automotive industry is the largest consumer of lead-acid batteries, with nearly every conventional car and truck containing one. The rise of electric vehicles (EVs) and hybrid cars also creates demand for these batteries in auxiliary functions. Furthermore, the growing need for renewable energy storage is opening new markets for large-scale lead-acid battery installations.

These batteries are favored for their reliability, recyclability, and cost-effectiveness compared to newer technologies. The established infrastructure for collection and recycling creates a circular economy for lead, with a significant portion of supply coming from recycled scrap material.

Global Lead Market Overview and Forecast

The international lead market is poised for a period of measurable growth coupled with shifting supply-demand dynamics. According to the International Lead and Zinc Study Group (ILZSG), the market is expected to see a growing surplus in the coming years. This indicates that supply is projected to outpace demand, which can influence global pricing.

The ILZSG forecasts a global surplus of 63,000 tonnes in 2024, expanding significantly to 121,000 tonnes in 2025.

Despite this surplus, overall consumption is still increasing. Demand for refined lead is expected to grow by 0.2% in 2024 to 13.13 million tonnes, followed by a stronger 1.9% increase in 2025 to reach 13.39 million tonnes. This growth is primarily fueled by economic expansion and infrastructure development in key regions.

Supply and Production Trends

Global mine production is on a steady upward trajectory. Estimates indicate a 1.7% increase to 4.54 million tonnes in 2024, with a further 2.1% rise to 4.64 million tonnes anticipated for 2025. This production growth is led by increased output from major mining nations like China, Australia, and Mexico.

The refined lead supply presents a slightly more complex picture. It is expected to dip slightly by 0.2% in 2024 to 13.20 million tonnes before rebounding with a 2.4% growth in 2025 to 13.51 million tonnes. This reflects the interplay between primary mine production and secondary production from recycling.

- Mine Supply 2024: 4.54 million tonnes (+1.7%)

- Mine Supply 2025: 4.64 million tonnes (+2.1%)

- Refined Supply 2024: 13.20 million tonnes (-0.2%)

- Refined Supply 2025: 13.51 million tonnes (+2.4%)

Leading Producers and Global Reserves

The landscape of lead production is dominated by a few key countries that control both current output and future reserves. Understanding this geographical distribution is critical for assessing the market's stability and long-term prospects.

China is the undisputed leader in production, accounting for a massive 2.4 million metric tons of annual mine production. This positions China as both the top producer and the top consumer of lead globally, influencing prices and trade flows. Other major producers include Australia (500,000 tons), the United States (335,000 tons), and Peru (310,000 tons).

Global Reserves and Future Supply Security

When looking at reserves—the identified deposits that are economically feasible to extract—the leaderboard shifts slightly. Australia holds the world's largest lead reserves, estimated at 35 million tons. This ensures its role as a critical supplier for decades to come.

China follows with substantial reserves of 17 million tons. Other countries with significant reserves include Russia (6.4 million tons) and Peru (6.3 million tons). The concentration of reserves in these regions highlights the geopolitical factors that can impact the lead supply chain.

- Australia: 35 million tons in reserves

- China: 17 million tons in reserves

- Russia: 6.4 million tons in reserves

- Peru: 6.3 million tons in reserves

Regional Market Analysis: Asia Pacific Dominance

The Asia Pacific region is the undisputed powerhouse of the global lead market, accounting for the largest share of both consumption and production. This dominance is fueled by rapid industrialization, urbanization, and a massive automotive sector. Countries like China and India are driving unprecedented demand for lead-acid batteries, which are essential for vehicles and growing energy storage needs.

China's role is particularly critical, representing over 50% of global lead use. The country's extensive manufacturing base for automobiles and electronics creates a consistent and massive demand for battery power. However, this growth is tempered by environmental regulations and government crackdowns on polluting smelters, which can periodically constrain supply and create market volatility.

Key Growth Drivers in Asia Pacific

Several interconnected factors are fueling the region's market expansion. The rapid adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) and two-wheelers, even with lithium-ion batteries for primary power, still requires lead-acid batteries for auxiliary functions. Furthermore, the push for renewable energy integration is creating a surge in demand for reliable backup power storage solutions across the continent.

- Urbanization and Infrastructure Development: Growing cities require more vehicles, telecommunications backup, and power grid storage.

- Growing Automotive Production: Asia Pacific is the world's largest vehicle manufacturing hub.

- Government Initiatives: Policies supporting renewable energy and domestic manufacturing boost lead consumption.

- Expanding Middle Class: Increased purchasing power leads to higher vehicle ownership and electronics usage.

Lead Market Dynamics: Supply, Demand, and Price Forecasts

The lead market is characterized by a delicate balance between supply and demand, which directly influences price trends. Current forecasts from the International Lead and Zinc Study Group (ILZSG) indicate a shift towards a growing market surplus. This anticipated surplus is a key factor that analysts believe will put downward pressure on lead prices through 2025.

Refined lead demand is projected to grow 1.9% to 13.39 million tonnes in 2025, but supply is expected to grow even faster at 2.4% to 13.51 million tonnes, creating a 121,000-tonne surplus.

Price sensitivity is also heavily influenced by Chinese economic policies and environmental inspections. Any disruption to China's smelting capacity can cause immediate price spikes, even amidst a broader surplus forecast. Investors and industry participants must therefore monitor both global stock levels and regional regulatory actions.

Analyzing the 2024-2025 Surplus

The projected surplus is not a sign of weak demand but rather of robust supply growth. Mine production is increasing steadily, and secondary production from recycling is becoming more efficient and widespread. This increase in available material is expected to outpace the steady, solid growth in consumption from the battery sector.

Key factors contributing to the surplus include:

- Increased Mine Output: New and expanded mining operations, particularly in Australia and Mexico.

- Efficiency in Recycling: Higher recovery rates from scrap lead-acid batteries.

- Moderating Demand Growth in China: A slowdown in the rate of GDP growth compared to previous decades.

The Critical Role of Lead Recycling

Recycling is a fundamental pillar of the lead industry's sustainability. Lead-acid batteries boast one of the highest recycling rates of any consumer product, often exceeding 99% in many developed economies. This closed-loop system provides a significant portion of the world's annual lead supply, reducing the need for primary mining.

The process of secondary production involves collecting used batteries, breaking them down, and smelting the lead components to produce refined lead. This method is more energy-efficient and environmentally friendly than primary production from ore. The Asia Pacific region, in particular, is seeing rapid growth in its secondary lead production capabilities.

Economic and Environmental Benefits of Recycling

The economic incentives for recycling are strong. Recycled lead is typically less expensive to produce than mined lead, providing cost savings for battery manufacturers. Furthermore, it helps stabilize the supply chain by providing a domestic source of material that is less susceptible to mining disruptions or export bans.

From an environmental standpoint, recycling significantly reduces the need for mining, which minimizes landscape disruption and water pollution. It also ensures that toxic battery components are disposed of safely, preventing soil and groundwater contamination. Governments worldwide are implementing stricter regulations to promote and mandate lead recycling.

- Resource Conservation: Reduces the depletion of finite natural ore reserves.

- Energy Efficiency: Recycling lead uses 35-40% less energy than primary production.

- Waste Reduction: Prevents hazardous battery waste from entering landfills.

Lead Market Segments: Battery Type Insights

The lead market can be segmented by the types of batteries produced, each serving distinct applications. The Starting, Lighting, and Ignition (SLI) segment is the largest, designed primarily for automotive engines. These batteries provide the short, high-current burst needed to start a vehicle and power its electrical systems when the engine is off.

Motive power batteries are another crucial segment, used to power electric forklifts, industrial cleaning machines, and other utility vehicles. Unlike SLI batteries, they are designed for deep cycling, meaning they can be discharged and recharged repeatedly. The third major segment is stationary batteries, used for backup power and energy storage.

Growth in Stationary and Energy Storage Applications

The stationary battery segment is experiencing significant growth, driven by the global need for uninterruptible power supplies (UPS) and renewable energy support. Data centers, hospitals, and telecommunications networks rely on lead batteries for critical backup power during outages. This demand is becoming increasingly important for grid stability.

Furthermore, as countries integrate more solar and wind power into their grids, the need for large-scale energy storage systems grows. While lithium-ion is often discussed for this role, advanced lead-carbon batteries are a cost-effective and reliable technology for many stationary storage applications, supporting the overall stability of renewable energy sources.

- SLI Batteries: Dominant segment, tied directly to automotive production and replacement cycles.

- Motive Power Batteries: Essential for logistics, warehousing, and manufacturing industries.

- Stationary Batteries: High-growth segment for telecom, UPS, and renewable energy storage.

Environmental and Regulatory Landscape

The environmental impact of lead production and disposal remains a critical focus for regulators worldwide. While lead is essential for modern technology, it is also a toxic heavy metal that poses significant health risks if not managed properly. This has led to a complex web of international regulations governing its use, particularly in consumer products like paint and plumbing.

In many developed nations, strict controls have phased out lead from gasoline, paints, and water pipes. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), for example, has mandated the replacement of lead service lines to prevent water contamination. These regulations have successfully reduced environmental exposure but have also shifted the industry's focus almost entirely to the battery sector, where containment and recycling are more controlled.

Global Regulatory Trends and Their Impact

The regulatory environment is constantly evolving, with a growing emphasis on extended producer responsibility (EPR). EPR policies make manufacturers responsible for the entire lifecycle of their products, including collection and recycling. This has accelerated the development of sophisticated take-back programs for lead-acid batteries, ensuring they do not end up in landfills.

In China, intermittent smog crackdowns and environmental inspections can temporarily shut down smelting operations, causing supply disruptions. These actions, while aimed at curbing pollution, create volatility in the global lead market. Producers are increasingly investing in cleaner technologies to comply with stricter emissions standards and ensure operational continuity.

- Occupational Safety Standards: Strict limits on worker exposure in smelting and recycling facilities.

- Product Bans: Prohibitions on lead in toys, jewelry, and other consumer goods.

- Recycling Mandates: Laws requiring the recycling of lead-acid batteries.

- Emissions Controls: Tighter restrictions on sulfur dioxide and particulate matter from smelters.

Technological Innovations in the Lead Industry

Despite being an ancient metal, lead is at the center of ongoing technological innovation, particularly in battery science. Researchers are continuously improving the performance of lead-acid batteries to compete with newer technologies like lithium-ion. Innovations such as lead-carbon electrodes are enhancing cycle life and charge acceptance, making these batteries more suitable for renewable energy storage.

Advanced battery designs are extending the application of lead into new areas like micro-hybrid vehicles (start-stop systems) and grid-scale energy storage. These innovations are crucial for the industry's long-term viability, ensuring that lead remains a relevant and competitive material in the evolving energy landscape.

Enhanced Flooded and AGM Battery Technologies

Two significant advancements are dominating the market: Enhanced Flooded Batteries (EFB) and Absorbent Glass Mat (AGM) batteries. EFB batteries offer improved cycle life over standard batteries for vehicles with basic start-stop technology. AGM batteries, which use a fiberglass mat to contain the electrolyte, provide even better performance, supporting more advanced auto systems and deeper cycling applications.

These technologies are responding to the automotive industry's demands for more robust electrical systems. As cars incorporate more electronics and fuel-saving start-stop technology, the requirements for the underlying battery become more stringent. The lead industry's ability to innovate has allowed it to maintain its dominant market position in the automotive sector.

Advanced lead-carbon batteries can achieve cycle lives exceeding 3,000 cycles, making them a cost-effective solution for renewable energy smoothing and frequency regulation.

Challenges and Opportunities for Market Growth

The lead market faces a dual landscape of significant challenges and promising opportunities. The primary challenge is its environmental reputation and the associated regulatory pressures. Competition from alternative battery chemistries, particularly lithium-ion, also poses a threat in specific high-performance applications like electric vehicles.

However, substantial opportunities exist in the renewable energy storage sector and the ongoing demand for reliable, cost-effective power solutions in developing economies. The established recycling infrastructure gives lead a distinct advantage in terms of sustainability and circular economy credentials, which are increasingly valued.

Navigating Competitive and Regulatory Pressures

The industry's future growth hinges on its ability to innovate and adapt. Continuous improvement in battery technology is essential to fend off competition. Simultaneously, proactive engagement with regulators to demonstrate safe and responsible production and recycling practices is crucial for maintaining social license to operate.

Market players are investing in cleaner production technologies and more efficient recycling processes to reduce their environmental footprint. By addressing these challenges head-on, the lead industry can secure its position as a vital component of the global transition to a more electrified and sustainable future.

- Opportunity: Growing demand for energy storage from solar and wind power projects.

- Challenge: Public perception and stringent environmental regulations.

- Opportunity: Massive automotive market requiring reliable SLI batteries.

- Challenge: Competition from lithium-ion batteries in certain applications.

Future Outlook and Strategic Recommendations

The long-term outlook for the lead market is one of steady growth, driven by its irreplaceable role in automotive and energy storage applications. The market size, valued at USD 24.38 billion in 2024, is projected to reach USD 38.57 billion by 2032, growing at a CAGR of 5.9%. This growth will be fueled by rising vehicle production and the global expansion of telecommunications and data centers requiring backup power.

The geographic focus will remain firmly on the Asia Pacific region, where economic development and urbanization are most rapid. Companies operating in this market should prioritize strategic investments in recycling infrastructure and advanced battery technologies to capitalize on these trends while mitigating environmental risks.

Strategic Imperatives for Industry Stakeholders

For miners, smelters, and battery manufacturers, several strategic actions are critical for future success. Diversifying into high-value segments like advanced energy storage can open new revenue streams. Building strong, transparent recycling chains will be essential for ensuring a sustainable and secure supply of raw materials.

Engaging in partnerships with automotive and renewable energy companies can help align product development with future market needs. Finally, maintaining a proactive stance on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) standards will be non-negotiable for attracting investment and maintaining market access.

- Invest in R&D: Focus on improving battery energy density and cycle life.

- Strengthen Recycling Networks: Secure supply and enhance sustainability credentials.

- Monitor Regulatory Changes: Adapt operations to comply with evolving global standards.

- Diversify Geographically: Explore growth opportunities in emerging markets beyond China.

Conclusion: The Enduring Role of Lead

In conclusion, the global lead market demonstrates remarkable resilience and adaptability. Despite well-documented environmental challenges and increasing competition, its fundamental role in providing reliable, recyclable, and cost-effective energy storage ensures its continued importance. The projected market growth to over USD 38 billion by 2032 underscores its enduring economic significance.

The industry's future will be shaped by its ability to balance economic growth with environmental responsibility. The high recycling rate of lead-acid batteries provides a strong foundation for a circular economy model. Technological advancements are continuously expanding the metal's applications, particularly in supporting the global transition to renewable energy.

The key takeaway is that lead is not a relic of the past but a material of the future. Its unique properties and well-established supply chain make it indispensable for automotive mobility, telecommunications, and power grid stability. As the world becomes more electrified, the demand for dependable battery technology will only increase, securing lead's place in the global industrial landscape for decades to come. Strategic innovation and responsible management will ensure this ancient metal continues to power modern life.

The Legacy of William Ramsay: Discovering the Noble Gases

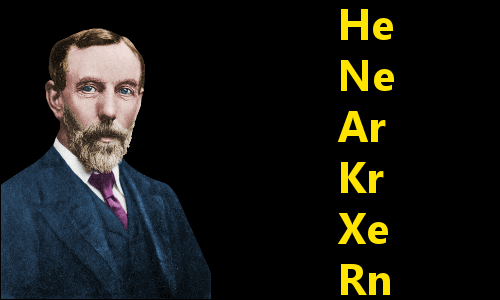

The scientific world was forever changed by the work of Sir William Ramsay, a Scottish chemist whose pioneering research filled an entire column of the periodic table. His systematic discovery of the noble gases—helium, argon, krypton, xenon, neon, and radon—fundamentally reshaped chemical theory. This article explores the life, groundbreaking experiments, and enduring impact of this Nobel Prize-winning scientist.

Early Life and Education of a Pioneering Chemist

The story of the noble gases begins in Scotland with the birth of William Ramsay. Born in Glasgow on October 2, 1852, he was immersed in an academic and industrial environment from a young age. His family's scientific background and the city's reputation for engineering excellence nurtured his burgeoning curiosity.

Formative Academic Training

Ramsay's formal academic journey saw him pursue an advanced degree far from home. He traveled to Germany to study under the guidance of renowned chemist Robert Bunsen at the University of Tübingen. There, he earned his Ph.D. in organic chemistry in 1872 with a dissertation on toluic acid and nitrotoluic acid. This rigorous training in German laboratory methods proved invaluable for his future work.

Upon returning to Great Britain, he held several academic posts, beginning at the University of Glasgow. It was during this period that his research interests began to shift. The meticulous approach he learned in Germany would later be applied to inorganic chemistry with revolutionary results. His eventual move to University College London (UCL) in 1887 provided the platform for his historic discoveries.

The Path to the First Noble Gas Discovery

Ramsay's world-changing work was sparked by a collaborative investigation into a scientific anomaly. In the early 1890s, physicist Lord Rayleigh (John William Strutt) published a puzzling observation. He had found a slight discrepancy between the density of nitrogen derived from air and nitrogen produced from chemical compounds.

Rayleigh's nitrogen from air was consistently denser. Intrigued by this mystery, Ramsay proposed a collaboration to determine its cause. This partnership between a chemist and a physicist would set the stage for one of the most significant discoveries in chemical history.

Isolating "Lazy" Argon

Ramsay devised an elegant experimental method to solve the nitrogen puzzle. He passed atmospheric nitrogen over heated magnesium, which reacted with the nitrogen to form magnesium nitride. He reasoned that any unreacted gas left over must be something else entirely. After removing all oxygen, carbon dioxide, and water vapor, he meticulously removed the nitrogen.

The resulting residual gas amounted to roughly 1 percent of the original air sample. Spectroscopic analysis revealed a set of spectral lines unknown to science, confirming a new element.

This new gas was remarkably unreactive. Ramsay and Rayleigh named it argon, from the Greek word "argos" meaning "idle" or "lazy." Their joint announcement in 1894 of this chemically inert constituent of the atmosphere stunned the scientific community and challenged existing atomic theory.

Building a New Group on the Periodic Table

The discovery of argon presented a profound conceptual problem for contemporary chemists. The known periodic table, as conceptualized by Dmitri Mendeleev, had no obvious place for a monatomic element with zero valence. Its atomic weight suggested it should sit between chlorine and potassium, but its properties were utterly alien.

Ramsay, however, saw a pattern. He hypothesized that argon might not be alone. He recalled earlier observations of a mysterious yellow spectral line in sunlight, detected during a 1868 solar eclipse and named "helium" after the Greek sun god, Helios. If a solar element existed, could it also be found on Earth and share argon's inert properties?

The Search for Helium on Earth

Guided by this bold hypothesis, Ramsay began a methodical search for terrestrial helium in 1895. He obtained a sample of the uranium mineral cleveite. By treating it with acid and collecting the resulting gases, he isolated a small, non-reactive sample. He then sent it for spectroscopic analysis to Sir William Crookes, a leading expert in spectroscopy.

The result was definitive. Crookes confirmed the spectrum's principal line was identical to that of the solar helium line. Ramsay had successfully isolated helium on Earth, proving it was not solely a solar element but a new terrestrial gas with an atomic weight lower than lithium. This discovery strongly supported his idea of a new family of elements.

- Argon and Helium Shared Key Traits: Both were gases, monatomic, chemically inert, and showed distinctive spectral lines.

- The Periodic Table Puzzle: Their placement suggested a new group between the highly reactive halogens (Group 17) and alkali metals (Group 1).

- A New Scientific Frontier: Ramsay was now convinced at least three more members of this family awaited discovery in the atmosphere.

Mastering the Air: Fractional Distillation Breakthrough

To find the remaining family members, Ramsay needed to process truly massive volumes of air. Fractional distillation of liquified air was the key technological leap. By cooling air to extremely low temperatures, it could be turned into a liquid. As this liquid air slowly warmed, different components would boil off at their specific boiling points, allowing for separation.

Ramsay, now working with a brilliant young assistant named Morris Travers, built a sophisticated apparatus to liquefy and fractionate air. They started with a large quantity of liquefied air and meticulously captured the fractions that evaporated after the nitrogen, oxygen, and argon had boiled away. What remained were the heavier, rarer components.

Their painstaking work in 1898 led to a cascade of discoveries. Through repeated distillation and spectroscopic examination, they identified three new elements in quick succession from the least volatile fractions of liquid air. Ramsay named them based on Greek words reflecting their hidden or strange nature, forever embedding their discovery story in their names.

The Systematic Discovery of Neon, Krypton, and Xenon

The year 1898 marked an unprecedented period of discovery in William Ramsay's laboratory. With a refined apparatus for fractional distillation of liquid air, he and Morris Travers embarked on a meticulous hunt for the remaining atmospheric gases. Their method involved isolating increasingly smaller and rarer fractions, each revealing a new element with unique spectral signatures.

The first of these three discoveries was krypton, named from the Greek word "kryptos" for "hidden." Ramsay and Travers found it in the residue left after the more volatile components of liquid air had evaporated. Following krypton, they identified neon, from "neos" meaning "new," which produced a brilliant crimson light when electrically stimulated. The final and heaviest of the trio was xenon, the "stranger," distinguished by its deep blue spectral lines.

Spectroscopic Proof of New Elements

Confirming the existence of these three new elements relied heavily on the analytical power of spectroscopy. Each gas produced a unique and distinctive spectrum when an electrical current was passed through it. The identification of neon was particularly dramatic, as described by Morris Travers.

Travers later wrote that the sight of the "glow of crimson light" from the first sample of neon was a moment of unforgettable brilliance and confirmation of their success.

These discoveries were monumental. In the span of just a few weeks, Ramsay and his team had expanded the periodic table by three new permanent gases. This rapid succession of discoveries solidified the existence of a completely new group of elements and demonstrated the power of systematic, precise experimental chemistry.

- Neon (Ne): Discovered by its intense crimson glow, later becoming fundamental to lighting technology.

- Krypton (Kr): A dense, hidden gas found in the least volatile fraction of liquid air.

- Xenon (Xe): The heaviest stable noble gas, identified by its unique blue spectral lines.

Completing the Group: The Radioactive Discovery of Radon

By 1900, five noble gases were known, but Ramsay suspected the group might not be complete. His attention turned to the new and mysterious field of radioactivity. He began investigating the "emanations" given off by radioactive elements like thorium and radium, gases that were themselves radioactive.

In 1910, Ramsay successfully isolated the emanation from radium, working with Robert Whytlaw-Gray. Through careful experimentation, they liquefied and solidified the gas, determining its atomic weight. Ramsay named it niton (from the Latin "nitens" meaning "shining"), though it later became known as radon.

Radon's Place in the Noble Gas Family

Radon presented a unique case. It possessed the characteristic chemical inertness of the noble gases, confirming its place in Group 18. However, it was radioactive, with a half-life of only 3.8 days for its most stable isotope, radon-222. This discovery powerfully linked the new group of elements to the pioneering science of nuclear physics and radioactivity.

The identification of radon completed the set of naturally occurring noble gases. Ramsay had systematically uncovered an entire chemical family, from the lightest, helium, to the heaviest and radioactive, radon. This achievement provided a complete picture of the inert gases and their fundamental properties.

Revolutionizing the Periodic Table of Elements

The discovery of the noble gases forced a fundamental reorganization of the periodic table. Dmitri Mendeleev's original table had no place for a group of inert elements. Ramsay's work demonstrated the necessity for a new group, which was inserted between the highly reactive halogens (Group 17) and the alkali metals (Group 1).

This addition was not merely an expansion; it was a validation of the periodic law itself. The atomic weights and properties of the noble gases fit perfectly into the pattern, reinforcing the predictive power of Mendeleev's system. The table was now more complete and its underlying principles more robust than ever before.

A New Understanding of Valence and Inertness

The existence of elements with a valence of zero was a radical concept. Before Ramsay's discoveries, all known elements participated in chemical bonding to some degree. The profound inertness of the noble gases led to a deeper theoretical understanding of atomic structure.

Their lack of reactivity was later explained by the Bohr model and modern quantum theory, which showed their stable electron configurations with complete outer electron shells. Ramsay's empirical discoveries thus paved the way for revolutionary theoretical advances in the 20th century.

- Structural Validation: The noble gases confirmed the periodicity of elemental properties.

- Theoretical Catalyst: Their inertness challenged chemists to develop new atomic models.

- Completed Groups: The periodic table gained a cohesive and logical Group 18.

Groundbreaking Experimental Techniques and Methodology

William Ramsay's success was not only due to his hypotheses but also his mastery of experimental precision. He was renowned for his ingenious laboratory techniques, particularly in handling gases and measuring their properties with exceptional accuracy. His work set new standards for analytical chemistry.

A key innovation was his refinement of methods for determining the molecular weights of substances in the gaseous and liquid states. He developed techniques for measuring vapor density with a precision that allowed him to correctly identify the monatomic nature of the noble gases, a critical insight that distinguished them from diatomic gases like nitrogen and oxygen.

The Mastery of Microchemistry

Many of Ramsay's discoveries involved working with extremely small quantities of material. The noble gases, especially krypton and xenon, constitute only tiny fractions of the atmosphere. Isolating and identifying them required microchemical techniques that were pioneering for the time.

His ability to obtain clear spectroscopic results from minute samples was a testament to his skill. Ramsay combined chemical separation methods with physical analytical techniques, creating a multidisciplinary approach that became a model for modern chemical research. His work demonstrated that major discoveries could come from analyzing substances present in trace amounts.

Ramsay's meticulous approach allowed him to work with samples of krypton and xenon that amounted to only a few milliliters, yet he determined their densities and atomic weights with remarkable accuracy.

Global Recognition and The Nobel Prize in Chemistry

The significance of William Ramsay's discoveries was swiftly acknowledged by the international scientific community. In 1904, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry "in recognition of his services in the discovery of the inert gaseous elements in air, and his determination of their place in the periodic system." This prestigious honor cemented his legacy.

Notably, his collaborator Lord Rayleigh received the Nobel Prize in Physics the same year for his related investigations of gas densities. This dual recognition highlighted the groundbreaking nature of their collaborative work. Ramsay's award was particularly historic, as he became the first British chemist to ever receive a Nobel Prize in that category.

Honors and Leadership in Science

Beyond the Nobel Prize, Ramsay received numerous other accolades throughout his illustrious career. He was knighted in 1902, becoming Sir William Ramsay, in recognition of his contributions to science. He was also a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) and received its prestigious Davy Medal in 1895.

Ramsay was deeply involved in the scientific community's leadership. He served as the President of the Chemical Society from 1907 to 1909 and was President of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1911. These roles allowed him to influence the direction of chemical research and education across Britain and beyond.

- Nobel Laureate (1904): Recognized for discovering the noble gases and defining their periodic table position.

- National Recognition: Knighted by King Edward VII for scientific service.

- Academic Leadership: Held presidencies in leading scientific societies.

The Widespread Applications of Noble Gases

The inert properties of the noble gases, once a scientific curiosity, have led to a vast array of practical applications that define modern technology. William Ramsay's pure samples of these elements unlocked possibilities he could scarcely have imagined, transforming industries from lighting to medicine.

Perhaps the most visible application is in lighting. Neon lighting, utilizing the gas's brilliant red-orange glow, revolutionized advertising and urban landscapes in the 20th century. Argon is used to fill incandescent and fluorescent light bulbs, preventing filament oxidation. Krypton and xenon are essential in high-performance flashlights, strobe lights, and specialized headlamps.

Critical Roles in Industry and Medicine

Beyond lighting, noble gases are indispensable in high-tech and medical fields. Helium is critical for cooling superconducting magnets in MRI scanners, enabling non-invasive medical diagnostics. It is also vital for deep-sea diving gas mixtures, welding, and as a protective atmosphere in semiconductor manufacturing.

Argon provides an inert shield in arc welding and titanium production. Xenon finds use in specialized anesthesia and as a propellant in ion thrusters for spacecraft. Even radioactive radon, while a health hazard, was historically used in radiotherapy.

Today, helium is a strategically important resource, with global markets and supply chains depending on its unique properties, which were first isolated and understood by Ramsay.

Later Career, Legacy, and Passing

After his monumental noble gas discoveries, Ramsay continued his research with vigor. He investigated the rate of diffusion of gases and pursued early work in radioactivity, including experiments that led to the first isolation of radon. He remained a prolific author and a respected professor at University College London until his retirement in 1912.

His influence extended through his students, many of whom became prominent scientists themselves. Morris Travers, his key collaborator, went on to have a distinguished career and wrote a definitive biography of Ramsay. The Ramsay Memorial Fellowship was established in his honor to support young chemists.

The Enduring Impact on Chemistry

Sir William Ramsay died on July 23, 1916, in High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, at the age of 63. His passing marked the end of an era of fundamental discovery in chemistry. His work fundamentally completed the periodic table as it was known in his time and provided the empirical foundation for the modern understanding of atomic structure.

His legacy is not merely a list of elements discovered. It is a testament to the power of systematic inquiry, meticulous experimentation, and collaborative science. He demonstrated how solving a small anomaly—the density of nitrogen—could unlock an entirely new realm of matter.

Conclusion: The Architect of Group 18

Sir William Ramsay's career stands as a pillar of modern chemical science. Through a combination of sharp intuition, collaborative spirit, and experimental genius, he discovered an entire family of elements that had eluded scientists for centuries. His work filled the final column of the periodic table, providing a complete picture of the elements that form our physical world.

The noble gases are more than just a group on a chart; they are a cornerstone of modern technology and theory. From the deep-sea diver breathing a helium mix to the patient undergoing an MRI scan, Ramsay's discoveries touch everyday life. His research bridged chemistry and physics, influencing the development of atomic theory and our understanding of valence and chemical bonding.

Final Key Takeaways from Ramsay's Work

- Expanded the Periodic Table: Ramsay discovered six new elements (He, Ne, Ar, Kr, Xe, Rn), creating Group 18 and validating the periodic law.

- Championed Collaborative Science: His partnership with Lord Rayleigh proved the power of interdisciplinary research.

- Mastered Experimental Precision: His techniques in handling and analyzing trace gases set new standards for chemical methodology.

- Connected Chemistry to New Frontiers: His work on radon linked inorganic chemistry to the emerging field of radioactivity.

- Launched a Technological Revolution: The inert properties he identified enabled countless applications in lighting, medicine, and industry.

In the annals of science, William Ramsay is remembered as the architect who revealed the noble gases. He showed that the air we breathe held secrets of profound chemical significance, patiently waiting for a researcher with the skill and vision to reveal them. His legacy is etched not only in the periodic table but in the very fabric of contemporary scientific and technological progress.