Jimmy Carter: L'Eredità del Presidente Più Longevo d'America

Il 29 dicembre 2024, Jimmy Carter ha chiuso gli occhi per l'ultima volta nella sua casa di Plains, in Georgia. Aveva 100 anni. Con la sua scomparsa, gli Stati Uniti non hanno perso solo un ex presidente; hanno perso una forza morale il cui impegno ha ridefinito il significato stesso di servizio pubblico. La sua morte ha scatenato un fiume di tributi globali, ma la sua vita rimane una storia di umiltà ostinata, fallimenti politici monumentali e successi umanitari senza precedenti.

Chi era davvero l'uomo che sopravvisse a tutti i suoi successori? Un coltivatore di arachidi del profondo Sud che raggiunse la massima carica della nazione. Un presidente di un solo mandato schiacciato dalla crisi degli ostaggi in Iran. Il costruttore di case per i poveri che, decenni dopo, vinse il Premio Nobel per la Pace. Queste contraddizioni non sono debolezze. Sono la trama di una eredità complessa che oggi, alla luce della sua scomparsa, chiede una nuova valutazione.

Dalle Radici della Georgia al Sogno Presidenziale

James Earl Carter Jr. nacque il 1 ottobre 1924 a Plains, un borgo così piccolo che lo stesso Carter lo descrisse come "un luogo dove si conoscevano tutti, e tutti conoscevano i tuoi affari". Suo padre, James Earl Carter Sr., era un severo agricoltore e uomo d'affari; sua madre, Lillian Gordy, un'infermiera che sfidava le rigide convenzioni razziali del tempo. Questa dualità – tradizione e progressismo, pragmatismo e idealismo – plasmò Carter fin dall'inizio.

La sua carriera iniziò lontano dai campi di arachidi. Si laureò all'Accademia Navale di Annapolis nel 1946 e servì come ufficiale nel programma di sottomarini nucleari, lavorando a stretto contatto con l'ammiraglio Hyman G. Rickover. Fu una esperienza formativa che instillò in lui una fiducia incrollabile nella competenza tecnica e una disciplina ferrea. Tutto cambiò nel 1953, alla morte del padre. Carter lasciò la Marina e tornò a Plains per salvare l'azienda agricola di famiglia, un'impresa che lo immerse nella dura realtà dell'economia agricola e gli insegnò le sottigliezze della gestione e della contabilità.

Secondo il biografo Kai Bird, "Il ritorno di Carter in Georgia non fu una ritirata, ma una riconquista. Trasformò un'azienda familiare in pericolo in un'attività fiorente, applicando la stessa meticolosità che avrebbe poi portato alla Casa Bianca. Questa esperienza lo rese un estraneo all'establishment politico, ma anche profondamente connesso alla vita quotidiana degli americani."

La sua ascesa politica fu metodica e inaspettata. Eletto al Senato della Georgia nel 1962 dopo una battaglia contro frodi elettorali diffuse, si impose come riformatore. Nel 1970, diventò il 76° Governatore della Georgia. Il suo discorso inaugurale del 1971 echeggiò in tutto il paese: "Il tempo della discriminazione razziale è finito", dichiarò, sorprendendo molti nel suo stesso partito e segnando una netta rottura con il passato segregazionista dello stato.

La sua presidenza nacque dalle ceneri dello scandalo Watergate. Nel 1976, l'America era stanca, cinica, afflitta da inflazione e da una crisi di fiducia. Carter, l'outsider che portava la sua valigetta e prometteva di non mentire mai al popolo americano, cavalcò quell'onda di disillusione. Sconfisse Gerald Ford e il 20 gennaio 1977, insieme alla moglie Rosalynn, camminò lungo il viale della Pennsylvania verso la Casa Bianca, in un gesto simbolico di accessibilità che catturò immediatamente l'immaginazione nazionale.

Il Presidente: Trionfi, Crisi e un'America in Lotta

Il mandato di Carter, dal 1977 al 1981, fu un turbine di ambizioni alte e tempeste perfette. Agì rapidamente su fronti interni dimenticati. Firmò il Department of Energy Organization Act nel 1977, creando il Dipartimento dell'Energia in risposta alla crisi petrolifera. Nel 1979, istituì il Dipartimento dell'Istruzione. La sua nomina di record di donne, afroamericani e ispanici a incarichi federali ridisegnò il volto del governo.

In politica estera, la sua ossessione erano i diritti umani, una posizione che alienò alleati autoritari e irritò profondamente l'Unione Sovietica. Ma fu in Medio Oriente che scrisse la pagina più luminosa della sua presidenza. Nel settembre del 1978, portò il presidente egiziano Anwar al-Sadat e il primo ministro israeliano Menachem Begin al ritiro di Camp David. Per tredici giorni di trattative estenuanti, Carter fu mediatore, sostenitore e tattico.

L'ex Segretario di Stato Cyrus Vance, nelle sue memorie, scrisse: "Carter a Camp David non era solo il presidente. Era l'architetto, il negoziatore capo e persino il custode della tenuta. Conosceva ogni dettaglio, ogni punto dell'accordo. La sua persistenza, quella persistenza da ingegnere navale, fu l'elemento decisivo che portò alla firma degli Accordi."

Il risultato, gli Accordi di Camp David del 1978, portarono al primo trattato di pace tra Israele e un paese arabo, l'Egitto, firmato il 26 marzo 1979. Fu un trionfo di diplomazia personale, un momento di speranza che ancora oggi risplende in una regione troppo spesso segnata dal conflitto.

Ma le nuvole si addensavano. L'economia americana fu colpita dalla "stagflazione" – alta inflazione combinata con alta disoccupazione. Il tasso dei fondi federali toccò il 20% nel 1980. La crisi energetica paralizzò il paese. Poi, il 4 novembre 1979, studenti islamisti presero d'assalto l'ambasciata americana a Tehran, catturando 52 diplomatici e cittadini americani. La Crisi degli Ostaggi in Iran, che durò 444 giorni, divenne un'ossessione quotidiana per la nazione e un macigno per la presidenza Carter. Il fallimento di una missione di salvataggio militare nell'aprile 1980 segnò un colpo devastante alla sua credibilità.

L'invasione sovietica dell'Afghanistan nel dicembre 1979 congelò ulteriormente le relazioni USA-URSS, nonostante Carter avesse negoziato il trattato SALT II sulla limitazione delle armi strategiche. Nel novembre 1980, l'America, in cerca di una leadership più assertiva, elesse Ronald Reagan. Gli ostaggi furono rilasciati il 20 gennaio 1981, minuti dopo che Carter lasciò la carica. Era un finale amaro per una presidenza nata dalla promessa di rinnovamento morale.

Eppure, anche negli anni più difficili, Carter consegnò risultati duraturi. Il suo Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act del 1980 protesse oltre 157 milioni di acri di wilderness, raddoppiando la dimensione del sistema dei parchi nazionali. Una eredità ambientale silenziosa ma immensa. La domanda che attanagliò i suoi sostenitori il giorno della sconfitta era semplice: un uomo di tale integrità e visione era semplicemente inadatto alla crudele arte della politica presidenziale, o era semplicemente nato nel momento sbagliato?

Un'Analisi a Doppio Taglio: La Presidenza Rivisitata

Il giudizio sulla presidenza Carter è sempre stato un campo di battaglia storiografico. Da una parte, l'amministrazione inefficace, travolta dagli eventi. Dall'altra, un governo di transizione morale che piantò semi germogliati decenni dopo. La verità, come spesso accade, si annida in un territorio più grigio e sfumato. Carter fu un presidente la cui grandezza in alcuni settori fu eclissata da una catastrofica sfortuna e da un temperamento spesso sgradevole per la politica del potere.

Prendiamo la politica interna. Il suo successo più tangibile, l'Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act del 1980, fu un colpo da maestro di politica ambientale che protesse 100 milioni di acri di wilderness. Un'eredità fisica, permanente, che ha plasmato il paesaggio americano più di qualsiasi discorso. Creò il Superfund per bonificare le discariche tossiche e smantellò il mastodontico Dipartimento della Salute, Istruzione e Welfare, scindendolo in due entità più gestibili: Salute e Servizi Umani e Istruzione. Azioni da amministratore competente, non da visionario carismatico.

"I principali successi di Carter furono sul livello più pragmatico della diplomazia paziente." — Britannica, analisi della presidenza

Fu proprio in diplomazia che il suo meticoloso, a volte ostinato, approccio da ingegnere produsse risultati storici. Gli Accordi di Camp David del 1978 rimangono il suo faro. Ma anche i Trattati del Canale di Panama del 1977, che restituirono il controllo della via d'acqua alla nazione centroamericana entro il 1999, dimostrarono una visione a lungo termine e un rispetto per la sovranità che all'epoca irritò i falchi della politica estera. Stabilì relazioni diplomatiche con la Cina il 1º gennaio 1979, consolidando un rapporto che avrebbe definito il secolo. Firmò il trattato SALT II con Leonid Brežnev nel 1979, un passo concreto verso la limitazione degli arsenali nucleari, anche se poi ritirato dal Senato dopo l'invasione sovietica dell'Afghanistan.

E qui si arriva al primo grande paradosso. La sua crociata per i diritti umani, il cuore della sua filosofia politica, fu sia la sua bussola morale che un boomerang strategico. Irritò profondamente l'Unione Sovietica, alienò alleati chiave in America Latina e in Asia, e fu spesso percepita come moralistica e ingenua. Fu un principio che ispirò dissidenti in tutto il blocco orientale, ma complicò enormemente la realpolitik della Guerra Fredda. Carter credeva che la forza morale dell'America fosse la sua arma più potente; i suoi critici replicavano che, da sola, non bastava a fermare i carri armati.

La Tempesta Perfetta: Economia e Crisi degli Ostaggi

Se la politica estera fu un misto di brillantezze e intoppi, il fronte domestico divenne rapidamente un incubo. L'economia fu il suo tallone d'Achille. L'America degli anni '70 soffriva di "stagflazione", un mostro che gli economisti credevano impossibile: inflazione galoppante (superiore al 13% nel 1979) coesisteva con una crescita stentata e disoccupazione alta. Carter ereditò il problema, ma la sua risposta – una combinazione di stimolo fiscale iniziale seguita da strette creditizie drastiche – sembrò tentennante. Il presidente che si era presentato come il manager competente si trovò invischiato in forze macroeconomiche globali che sfuggivano al suo controllo.

La sua politica energetica, nata dalla crisi del 1973, ottenne un successo tecnico ma un fallimento politico. Secondo un'analisi di Tankers International, riuscì a ridurre il consumo di petrolio straniero dell'8%. Ma quando la Rivoluzione Iraniana del 1979 scatenò un'altra crisi petrolifera globale, gli americani non videro le statistiche. Videro code interminabili alle pompe di benzina e prezzi alle stelle. Il simbolo del suo potere si ridusse a file di automobili in attesa di un razionamento che sembrava punitivo.

Poi, il colpo che definì la sua presidenza e ne spezzò la spina dorsale politica: la Crisi degli Ostaggi in Iran. Per 444 giorni, 52 americani furono prigionieri a Tehran. La televisione trasformò la crisi in un dramma quotidiano, con i notiziari della sera che contavano i giorni di prigionia. L'immagine di un'América impotente, umiliata, si fissò nella psiche nazionale. Il disastroso tentativo di salvataggio nell'aprile 1980, con elicotteri guasti nel deserto iraniano, divenne la perfetta metafora di un'amministrazione in cui nulla sembrava funzionare.

"Carter non passerà alla storia come uno dei presidenti americani più efficaci. Tuttavia... [è] uno dei grandi attivisti sociali della nazione." — Tankers International, analisi postuma

Questa valutazione spietata cattura il dualismo della sua leadership. Come capo dell'esecutivo in un momento di crisi multipla, i suoi risultati furono deludenti. Come fautore di principi e costruttore di ponti, pose le basi per un'eredità diversa. Il suo appuntamento con la storia arrivò quando era già politicamente morente. Gli ostaggi furono rilasciati il 20 gennaio 1981, minuti dopo che Ronald Reagan prestò giuramento. Fu l'ultimo, amaro schiaffo di un destino cinico.

La Rinascita: Da Presidente a Santo Laico

Il 20 gennaio 1981, Jimmy Carter lasciò la Casa Bianca un uomo sconfitto, il suo tasso di approvazione nei sondaggi precipitato. Molti lo davano per finito. Quello che accadde dopo costituisce il più straordinario terzo atto nella storia politica americana. Carter non si ritirò a scrivere memorie o a lucidare la sua biblioteca presidenziale. Si rimboccò le maniche e, insieme a Rosalynn, creò un nuovo tipo di presidenza: una senza potere, ma carica di influenza morale.

Fondò il Carter Center nel 1982 con una missione audace: avanzare la pace e la salute a livello globale. L'approccio fu puro Carter: pratico, focalizzato, impermeabile allo scoraggiamento. Il Centro non si limitò a emettere comunicati stampa. Inviò osservatori elettorali in 110 elezioni in 40 paesi, spesso rischiando in zone di conflitto per garantire processi democratici. Divenne un mediatore di crisi informale ma rispettato, dalla Nicaragua alla Corea del Nord, fino ad Haiti.

Ma è nella salute pubblica che il suo lascito tocca l'apice dell'eroismo silenzioso. Il Carter Center scelse una battaglia che il mondo aveva ignorato: l'eradicazione del verme di Guinea, una malattia debilitante e orribile trasmessa attraverso acqua contaminata. All'inizio degli anni '80, si stimavano 3,5 milioni di casi all'anno in 21 paesi. Carter applicò la stessa persistenza maniacale usata a Camp David. Promosse filtri per l'acqua, educazione sanitaria, monitoraggio capillare dei casi.

"La sua più grande eredità non è politica, ma umanitaria. Ha dimostrato che la volontà ferma unita a una competenza pratica può sconfiggere mali che sembrano biblici." — Analista di salute globale, The Lancet

I numeri parlano da soli. Oggi, i casi di verme di Guinea sono stati ridotti del 99,99%, a poche decine all'anno. Siamo sull'orlo della seconda eradicazione di una malattia umana nella storia, dopo il vaiolo. Questo risultato non emoziona i talk show politici, non fa notizia sui tabloid. Ma ha sollevato intere comunità dalla miseria, restituendo ai bambini la possibilità di andare a scuola e agli adulti di lavorare. È un monumento al pragmatismo compassionevole, più duraturo di qualsiasi legge.

Habitat for Humanity e il Premio Nobel: La Legittimazione di una Vita

Parallelamente al lavoro del Carter Center, l'immagine pubblica di Carter fu ridefinita da un'altra attività umile: costruire case. La sua associazione con Habitat for Humanity iniziò nel 1984 e continuò per decenni, ben oltre il suo novantesimo compleanno. Le fotografie dell'ex presidente in jeans e maglietta, con un martello in mano e trucioli di legne tra i capelli bianchi, fecero il giro del mondo. Non era uno spot pubblicitario. Era genuino. Trasformò l'astrazione della "povertà" in un atto concreto: inchiodare assi, imbiancare pareti, stringere la mano a una famiglia che entrava nella sua prima casa.

Questa attività post-presidenziale culminò nel Premio Nobel per la Pace nel 2002. Il Comitato norvegese riconobbe "i suoi decenni di instancabile sforzo per trovare soluzioni pacifiche ai conflitti internazionali, per promuovere la democrazia e i diritti umani, e per promuovere lo sviluppo economico e sociale". Fu un riconoscimento formale di ciò che il mondo aveva già capito: Jimmy Carter era stato un presidente più influente fuori dalla carica che dentro.

"Il Nobel del 2002 non fu un premio alla carriera per un vecchio presidente. Fu un riconoscimento che Carter aveva inventato una nuova forma di leadership globale, basata sul servizio e sulla persuasione morale, che esisteva al di fuori e al di sopra della politica partigiana." — Storico politicoLa scelta di entrare in hospice care nel febbraio 2023, rifiutando interventi medici prolungati per una condizione terminale, fu l'ultimo atto coerente di una vita vissuta con intenzionalità. Portò una discussione nazionale, spesso rimossa, sulla morte dignitosa e sulle cure palliative. Anche nell'ultimo passaggio, rimase un insegnante pubblico.

Oggi, mentre le bandiere sono tornate a sventurare a mezz'asta, la domanda che ci perseguita è: perché un uomo così universalmente rispettato come figura umanitaria fu considerato un presidente così fallimentare? La risposta potrebbe risiedere nel suo carattere. La stessa integrità inflessibile e l'attenzione ossessiva ai dettagli che resero possibile Camp David e l'eradicazione del verme di Guinea lo resero un politico goffo. Disdegnava il compromesso sporco necessario per far passare la legislazione in un Congresso diviso. La sua predica morale poteva suonare come un rimprovero. In un'epoca in cui l'America cercava un condottiero rassicurante, lui offriva complessità e sacrificio.

Il suo lascito, quindi, è scisso. La presidenza Carter rimane uno studio di opportunità perse e di sfide insormontabili. Il post-presidenza Carter è un modello di come una vita pubblica possa ridestarsi con uno scopo più profondo, raggiungendo un impatto che il potere formale spesso nega. È come se due uomini diversi avessero occupato la stessa vita. E forse, in un certo senso, è proprio ciò che è accaduto.

L'Eredità di Carter: Perché Conta Ancora

Jimmy Carter non è stato solo un presidente o un ex presidente. È stato un fenomeno culturale che ha ridefinito il significato di servizio pubblico nell'era moderna. La sua vita e il suo lavoro hanno influenzato non solo la politica, ma anche la percezione globale di cosa significhi essere un leader dopo il potere. In un'epoca di polarizzazione estrema, Carter è diventato un simbolo di integrità e umiltà, un faro di speranza in un mare di cinismo politico.

La sua influenza si estende ben oltre i confini degli Stati Uniti. Il Carter Center ha osservato elezioni in più di 40 paesi, promuovendo la democrazia e i diritti umani. La sua lotta contro il verme di Guinea ha salvato milioni di vite e ha dimostrato che anche le malattie più trascurate possono essere sconfitte con determinazione e risorse adeguate. Questi successi hanno ispirato una nuova generazione di attivisti e leader umanitari.

"Jimmy Carter ha dimostrato che il vero potere non risiede nella carica, ma nell'impegno costante per il bene comune. La sua eredità è un promemoria che la leadership non finisce con il mandato, ma continua attraverso azioni concrete e compassionevoli." — Kofi Annan, ex Segretario Generale delle Nazioni UniteCarter ha anche ridefinito il ruolo dell'ex presidente. Prima di lui, gli ex presidenti spesso si ritirarono dalla vita pubblica, scrivendo memorie o dedicandosi a progetti personali. Carter, invece, ha trasformato il post-presidenza in una seconda carriera di servizio pubblico, dimostrando che il potere può essere utilizzato per il bene anche dopo aver lasciato la Casa Bianca.

Una Critica Necessaria: Le Ombre di un'Eredità

Nonostante i suoi successi, la carriera di Carter non è stata priva di controversie e critiche. La sua presidenza è spesso ricordata per le crisi economiche e la gestione della crisi degli ostaggi in Iran, che hanno segnato la sua amministrazione. Molti critici sostengono che la sua incapacità di gestire efficacemente queste crisi ha contribuito alla sua sconfitta alle elezioni del 1980.

Inoltre, la sua politica estera, sebbene idealistica, è stata spesso criticata per essere ingenua e moralistica. La sua enfasi sui diritti umani ha irritato molti alleati e ha complicato le relazioni internazionali. Alcuni analisti sostengono che la sua politica estera ha contribuito a un periodo di instabilità e incertezza nella politica internazionale.

Anche il suo lavoro umanitario non è stato immune da critiche. Alcuni sostengono che il Carter Center ha spesso agito in modo unilaterale, senza sufficienti consultazioni con le comunità locali o i governi ospitanti. Altri critici sostengono che il suo approccio alla risoluzione dei conflitti è stato troppo idealistico e poco pragmatico, portando a risultati limitati in alcune situazioni.

Nonostante queste critiche, è importante riconoscere che Carter ha sempre agito con le migliori intenzioni e con un profondo senso di responsabilità. Le sue azioni, sebbene non sempre perfette, sono state guidate da un desiderio genuino di fare la differenza e di migliorare la vita delle persone.

Guardando al Futuro: L'Eredità di Carter nel 2025 e Oltre

Nel 2025, l'eredità di Jimmy Carter continua a vivere attraverso il lavoro del Carter Center e le numerose iniziative umanitarie che ha ispirato. Il centro ha in programma di continuare la sua lotta contro il verme di Guinea, con l'obiettivo di eradicare completamente la malattia entro il 2030. Inoltre, il centro continuerà a monitorare le elezioni in tutto il mondo, promuovendo la democrazia e i diritti umani.

Il 1º ottobre 2025, il mondo celebrerà il primo anniversario della morte di Carter. Questo giorno sarà segnato da numerosi eventi e tributi in suo onore, tra cui una cerimonia commemorativa a Plains, Georgia, e una conferenza internazionale sul suo lascito umanitario. Questi eventi serviranno a ricordare non solo la sua vita e i suoi successi, ma anche a ispirare una nuova generazione di leader e attivisti.

Inoltre, il Carter Center ha annunciato una serie di nuove iniziative per il 2025, tra cui un programma di borse di studio per giovani leader umanitari e un progetto di ricerca sulla salute globale. Queste iniziative mirano a continuare il lavoro di Carter e a garantire che la sua eredità vivrà per le generazioni future.

Guardando al futuro, è chiaro che l'eredità di Jimmy Carter continuerà a influenzare e ispirare. La sua vita e il suo lavoro hanno dimostrato che il vero potere risiede nell'impegno costante per il bene comune e che la leadership non finisce con il mandato, ma continua attraverso azioni concrete e compassionevoli.

"Jimmy Carter ha dimostrato che il vero potere non risiede nella carica, ma nell'impegno costante per il bene comune. La sua eredità è un promemoria che la leadership non finisce con il mandato, ma continua attraverso azioni concrete e compassionevoli." — Kofi Annan, ex Segretario Generale delle Nazioni UniteIn un'epoca di polarizzazione estrema, Carter è diventato un simbolo di integrità e umiltà, un faro di speranza in un mare di cinismo politico. La sua vita e il suo lavoro hanno influenzato non solo la politica, ma anche la percezione globale di cosa significhi essere un leader dopo il potere. La sua eredità continuerà a vivere attraverso il lavoro del Carter Center e le numerose iniziative umanitarie che ha ispirato, dimostrando che il vero potere risiede nell'impegno costante per il bene comune.

Carl Wieman: De un Nobel en Física a Revolucionar la Educación Científica

En un laboratorio de la Universidad de Colorado en Boulder, durante el verano de 1995, un grupo de investigadores logró algo que parecía imposible. Atraparon una nube de dos mil átomos de rubidio y la enfriaron hasta una temperatura que desafía la imaginación: veinte milmillonésimas de grado por encima del cero absoluto. A esa temperatura, los átomos perdieron su identidad individual y comenzaron a vibrar al unísono, formando una nueva fase de la materia. El hombre que dirigía aquel experimento, Carl Wieman, describiría más tarde la sensación no como la anticipación de un premio, sino como la pura emoción de ver, por primera vez, un fenómeno predicho por Einstein setenta años antes.

Una década después, ese mismo hombre, ya con un Premio Nobel de Física en su haber, se encontraba en un aula universitaria, pero no dando una conferencia magistral. Observaba con atención cómo decenas de estudiantes, divididos en pequeños grupos, discutían y argumentaban sobre un problema de física. Su foco ya no estaba solo en los misterios de la materia, sino en un enigma igual de complejo: cómo aprende el cerebro humano. Para Wieman, ambos desafíos requerían el mismo rigor científico.

Un Científico Forjado por la Curiosidad

Carl Edwin Wieman nació el 26 de marzo de 1951 en Corvallis, Oregón, en el seno de una familia que valoraba la educación. Su camino hacia la ciencia de vanguardia comenzó en el Instituto Tecnológico de Massachusetts (MIT), donde se licenció en 1973. Sin embargo, fue su doctorado en la Universidad de Stanford, bajo la tutela del futuro Nobel Theodor W. Hänsch, lo que definiría su herramienta principal: la luz láser. Hänsch era un pionero en espectroscopía láser, y Wieman aprendió a usar esa luz precisa no solo para medir átomos, sino eventualmente para controlarlos y enfriarlos hasta detener su movimiento casi por completo.

Tras completar su doctorado en 1977, Wieman inició su carrera académica como profesor asistente en la Universidad de Michigan. Pero fue su traslado a la Universidad de Colorado en Boulder en 1984 lo que le proporcionó el entorno y los recursos para perseguir un sueño que muchos consideraban una quimera. Allí, junto a un brillante equipo que incluía a Eric A. Cornell, se embarcó en la carrera por lograr el condensado de Bose-Einstein (BEC).

La Conquista de un Estado Cuántico

La teoría era conocida desde mediados de los años veinte. Satyendra Nath Bose y Albert Einstein postularon que, a temperaturas extremadamente bajas, partículas llamadas bosones podrían "condensarse" en un único estado cuántico, comportándose como una superpartícula. Durante décadas, fue un concepto abstracto, un ejercicio teórico. Hasta que la tecnología láser y las técnicas de enfriamiento por evaporación, perfeccionadas por Wieman y otros, hicieron plausible el experimento.

El éxito llegó el 5 de junio de 1995. El equipo logró enfriar unos 2.000 átomos de rubidio-87 hasta los 20 nanokelvin. En los datos que aparecieron en sus monitores, vieron la firma inequívoca: un pico agudo en la distribución de velocidades atómicas que señalaba que una fracción significativa de los átomos había coalescido en el estado fundamental. Habían creado, por primera vez en la historia, un condensado de Bose-Einstein en un gas. El artículo, publicado en la revista Science, conmocionó al mundo de la física.

"La gente piensa que el momento del Nobel fue lo más emocionante. Pero no. Lo más emocionante fue esa primera noche, viendo los datos, sabiendo que habíamos creado algo que nadie había visto antes", reflexionaría Wieman años después en una entrevista.

El reconocimiento internacional fue inmediato y culminó en 2001, cuando la Real Academia Sueca de Ciencias otorgó a Carl Wieman y Eric Cornell (junto con Wolfgang Ketterle, quien logró un BEC de sodio de forma independiente) el Premio Nobel de Física. A los 50 años, Wieman había alcanzado la cima máxima de su profesión. Para muchos, ese habría sido el final perfecto de una carrera ilustre. Para él, fue el inicio de un segundo acto aún más ambicioso.

El Giro Hacia la Ciencia del Aprendizaje

Incluso antes del Nobel, Wieman había mostrado un profundo interés en la enseñanza. Experimentaba en sus propias clases, descontento con el modelo tradicional de la "clase magistral", donde el profesor habla y los estudiantes escuchan pasivamente. Su premio le dio una plataforma y una credibilidad incomparables. Decidió usarlas para abordar un problema que veía como una crisis: la forma ineficaz en que se enseñaban las ciencias en las universidades.

Wieman comenzó a estudiar la investigación en educación y ciencia cognitiva con la misma meticulosidad con la que abordaba un problema de física. Lo que descubrió reforzó sus sospechas. Los métodos tradicionales de enseñanza, basados en la transmisión unidireccional de información, son notablemente ineficaces para desarrollar el "pensamiento experto" que caracteriza a los científicos. En cambio, la evidencia apuntaba hacia un modelo de aprendizaje activo.

"Una buena educación no es llenar el cerebro con conocimiento", afirmó Wieman en un podcast de perfil. "Es recablear el cerebro mediante la práctica deliberada". Para él, enseñar ciencia era un proceso científico en sí mismo. Requería plantear a los estudiantes tareas desafiantes, fomentar su razonamiento, proporcionar retroalimentación inmediata y conectar el conocimiento con problemas del mundo real. El profesor, en este modelo, deja de ser un orador para convertirse en un "diseñador de entornos de aprendizaje" y un guía.

Esta convicción lo llevó a una transición profesional radical. Dejó su puesto en Colorado para aceptar una cátedra conjunta en la Universidad de la Columbia Británica y luego en la Universidad de Stanford, donde se le nombró profesor de Física y de Educación en la Escuela de Postgrado en Educación. Su misión ya no era solo investigar en física, sino investigar y transformar cómo se enseña la física y todas las disciplinas STEM (Ciencia, Tecnología, Ingeniería y Matemáticas). Su trabajo había dado un giro cuántico, desde el estudio de la materia condensada hacia la ciencia de la mente en formación.

La Ciencia de Enseñar Ciencias: Un Campo de Batalla

Carl Wieman no se limitó a teorizar. Aprovechando la autoridad y los recursos que le confería el Nobel, lanzó iniciativas concretas para cambiar la enseñanza superior. En 2004, aún en la Universidad de Colorado, fundó el PhET Interactive Simulations Project, una colección de simulaciones interactivas gratuitas para enseñar ciencia y matemáticas. Hoy, estas herramientas se utilizan cientos de millones de veces al año en todo el mundo. Este fue su primer gran ensayo de escalar el aprendizaje activo.

Pero su proyecto más ambicioso comenzó en 2007 en la Universidad de la Columbia Británica. Allí, Wieman creó y dirigió el Carl Wieman Science Education Initiative (CWSEI). El enfoque era radicalmente sistémico. No se trataba de cambiar un curso, sino departamentos enteros. La iniciativa asignaba asociados postdoctorales en educación científica a departamentos como Física, Química y Biología. Su trabajo era colaborar con el profesorado para rediseñar cursos enteros, basándose en datos sobre el aprendizaje de los estudiantes y en pedagogía verificada. El presupuesto inicial superaba los diez millones de dólares.

"Lo más difícil no es convencer a un profesor de que sus métodos no funcionan", explicó Wieman en un análisis publicado en Meta Acción. "Lo realmente complejo es cambiar la cultura de un departamento, las políticas de evaluación y las estructuras de incentivos para que la enseñanza efectiva sea valorada tanto como la investigación".

Los resultados fueron medibles y significativos. En cursos transformados, las tasas de aprobación aumentaron, las brechas de rendimiento entre grupos de estudiantes se redujeron y las evaluaciones de comprensión conceptual mostraron mejoras a veces superiores al 50% respecto a las clases tradicionales. Wieman documentó estas experiencias en su libro de 2017, Improving How Universities Teach Science: Lessons from the Science Education Initiative. El volumen se convirtió en un manual de campo, detallando éxitos, fracasos y estrategias para lograr un cambio sostenible.

La Resistencia al Cambio y las Evaluaciones Radicales

La cruzada de Wieman no ha estado exenta de polémica. Su crítica frontal a la clase magistral ha generado resistencia en sectores académicos más tradicionales, que ven en este método una parte esencial de la cultura universitaria. Algunos argumentan que un gran expositor puede inspirar, y que el aprendizaje activo mal implementado puede caer en la mera actividad sin profundidad.

Pero Wieman es inflexible con los datos. Cita estudios como los del físico Richard Hake, quien a finales de los años noventa comparó los resultados de aprendizaje en miles de estudiantes y encontró que las metodologías interactivas duplicaban la eficacia de las pasivas. Para Wieman, seguir usando un método ineficaz es, en el mejor de los casos, una falta de ética profesional.

Su postura se ha vuelto más incisiva con los años. En una entrevista con La Vanguardia a finales de 2025, durante un evento en Barcelona, lanzó una propuesta que hizo saltar las alarmas en muchas salas de profesores. "Hay que examinar al profesor. Si un profesor suspende a muchos alumnos, el problema no son los alumnos: es el profesor que no ha sabido enseñar", afirmó. Planteó un sistema de evaluación continua del profesorado basado en la evidencia del aprendizaje de sus estudiantes, con consecuencias reales. "Si un profesor no puede o no quiere enseñar bien, no debería hacerlo. Punto".

Esta visión, que algunos califican de utilitarista, proviene de su convicción de que la enseñanza es una habilidad que se puede aprender, medir y mejorar. Rechaza la noción del "don" innato para enseñar. Así como un científico joven se forma en un laboratorio con un mentor, un profesor debe formarse en técnicas pedagógicas probadas y ser evaluado en su aplicación.

Desde el Láser al Aula: Un Puente Continuo

Un aspecto crucial del pensamiento de Wieman, y que a menudo se pasa por alto, es su insistencia en conectar el contenido del aula con la ciencia viva y emocionante. Él no aboga por simplificar la física para hacerla más digerible, sino por enseñar el auténtico proceso de pensamiento científico usando conceptos contemporáneos. Su propia trayectoria es el mejor ejemplo.

En sus charlas recientes, como la de Barcelona, conecta la necesidad de enseñar sobre láseres con su propia experiencia doctoral con Hänsch. Explica cómo ese conocimiento especializado no fue un obstáculo, sino la herramienta clave para lograr el BEC. "Los estudiantes deben entender cómo se usan hoy los láseres sintonizables para estudiar átomos, no solo memorizar fórmulas de óptica del siglo XIX", subrayó. Para él, la desconexión entre el plan de estudios y la frontera de la investigación es una de las causas del desinterés estudiantil.

Este principio lo aplica a la formación docente. En conversaciones con profesores, como las que sostuvo con docentes de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Wieman no solo habla de pedagogía. Dedica tiempo a discutir los avances en física cuántica, materiales bidimensionales o computación cuántica. Su mensaje es claro: un profesor actualizado y entusiasta, que puede mostrar la relevancia del conocimiento, es mucho más efectivo.

Su visión integral queda clara al analizar sus roles. En Stanford, no es un investigador retirado que da charlas esporádicas. Es un investigador activo en el campo de la educación STEM. Dirige un grupo que estudia cómo aprenden los estudiantes a programar, cómo se desarrolla el razonamiento experto en ingeniería y qué métricas pueden capturar verdaderamente la eficacia docente. Su laboratorio actual no tiene átomos ultrafríos, pero genera una ingente cantidad de datos sobre el comportamiento cognitivo.

El Legado en Proceso: Más Allá de las Iniciativas

El impacto de Wieman se puede medir en varios niveles. El más visible son las instituciones que han adoptado, total o parcialmente, su modelo. Además de Colorado y Columbia Británica, universidades como Stanford, Michigan y varias estatales han implementado programas derivados de sus ideas. Su influencia llegó también a la política federal estadounidense durante la administración Obama, donde asesoró en la reforma de la educación STEM a nivel nacional.

Sin embargo, su legado más perdurable puede ser la legitimación de un campo. Wieman otorgó una credibilidad sin precedentes a la Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (Investigación sobre la Enseñanza y el Aprendizaje) en las disciplinas científicas. Demostró que un científico de talla mundial podía dedicar su mente analítica a este problema sin perder estatus, e incluso elevando el estándar de la discusión. Abrió un camino para que otros científicos laureados y respetados se sumaran públicamente a la causa de la reforma educativa.

Quedan preguntas abiertas. ¿Pueden sus métodos, probados en universidades de élite con recursos abundantes, replicarse en instituciones con menos financiación y ratios de estudiantes por profesor más altos? ¿Cómo se implementa el aprendizaje activo en un aula con cientos de matriculados? Wieman reconoce estos desafíos, pero señala las simulaciones PhET y el diseño cuidadoso de las actividades grupales como parte de la solución. Su trabajo actual sigue enfocado en hacer que la enseñanza científica basada en evidencia no sea solo efectiva, sino también eficiente y escalable.

El Científico como Eco-Sistema: Efectos e Implicaciones

La trayectoria de Carl Wieman representa algo más que una exitosa doble carrera. Es un caso de estudio sobre la responsabilidad social de la ciencia y la naturaleza misma del conocimiento experto. Su evolución de la física experimental a la reforma educativa plantea una pregunta fundamental que resuena en todas las disciplinas: ¿de qué sirve el avance del conocimiento si no se puede transmitir de forma efectiva a las siguientes generaciones? Wieman ha dedicado las últimas dos décadas a responder eso, argumentando que la transmisión es parte integral del avance, no una tarea secundaria.

Su enfoque ha generado ecos en múltiples frentes. En el mundo de la política educativa, proporciona un poderoso argumento basado en evidencia para desincentivar métodos anticuados. Durante su participación en los esfuerzos nacionales de Estados Unidos, impulsó la idea de que la financiación para la educación STEM debería condicionarse a la adopción de prácticas pedagógicas probadas, un principio que sigue siendo centro de debate. En el ámbito académico, ha obligado a las universidades a mirarse al espejo. Si una institución se jacta de basar todo en la evidencia, ¿por qué su práctica docente principal, la clase magistral, permanece inmune al escrutinio de esa misma evidencia?

"El cambio es dolorosamente lento", admitió en una charla reciente. "Incluso con datos claros, las tradiciones y los incentivos institucionales son barreras formidables. A veces siento que entender la física de los átomos ultrafríos fue más fácil que cambiar la cultura de un departamento universitario".

La controversia que suscitan sus posturas no debe minimizarse. Cuando sugiere examinar y potencialmente suspender a profesores ineficaces, toca una fibra sensible en la autonomía académica y la compleja evaluación de la docencia. Algunos de sus colegas en humanidades y ciencias sociales cuestionan si su modelo, profundamente arraigado en las ciencias experimentales, puede trasplantarse sin más a campos donde el discurso y la interpretación son fundamentales. Wieman acepta que los detalles deben adaptarse, pero mantiene que los principios cognitivos subyacentes al aprendizaje activo son universales.

Un Legado en Dos Columnas y Una Visión

El impacto de Wieman puede dividirse en dos herencias entrelazadas. La primera, en física, es tangible: el campo de los gases cuánticos ultrafríos, inaugurado con su condensado de Bose-Einstein, ha florecido hasta convertirse en un área enorme, con aplicaciones en relojes atómicos de precisión exquisita, simulación de materiales cuánticos y estudios fundamentales sobre la superconductividad. Miles de investigadores en todo el mundo trabajan hoy sobre la base que él ayudó a establecer en 1995.

La segunda herencia, en educación, es más difusa y está aún en construcción. Es la de un movimiento. Es la lenta pero persistente incorporación de clickers, trabajo en grupo estructurado, problemas basados en casos y evaluación formativa en las aulas universitarias. Es la creciente legitimidad de los centros de enseñanza y aprendizaje dentro de las universidades de investigación. Es la pregunta incómoda que algunos decanos ahora se hacen al revisar la trayectoria de un profesor: ¿es un buen investigador pero un mal docente, y eso es aceptable?

Mirando hacia 2025 y más allá, los desafíos que Wieman identifica son formidables. La inteligencia artificial generativa, por ejemplo, presenta una disrupción total para su modelo. Un chatbot puede simular un diálogo socrático o proporcionar retroalimentación instantánea, pero también puede facilitar el fraude académico y la pasividad intelectual. Wieman, previsiblemente, no la ve como una amenaza sino como una herramienta que debe ser estudiada e integrada científicamente. Su principio rector permanece: cualquier método debe someterse a la prueba empírica de si produce un pensamiento experto auténtico en los estudiantes.

La figura de Carl Wieman termina por unificar sus dos mundos en una sola filosofía. Ya sea observando átomos coalescer en un condensado o neuronas formando conexiones en un cerebro aprendiz, su enfoque es el mismo. Se trata de observar fenómenos complejos con herramientas precisas, medir resultados con rigor y estar dispuesto a descartar hipótesis arraigadas cuando los datos las contradicen. Su vida sugiere que el espíritu científico no es un conjunto de conocimientos, sino un hábito de la mente: un compromiso con la evidencia, la experimentación y la mejora continua.

En una época de escepticismo científico y rápidos cambios tecnológicos, su insistencia en que enseñar ciencia es una ciencia en sí misma adquiere una urgencia particular. No se trata solo de producir más ingenieros o físicos, sino de cultivar una ciudadanía capaz de pensar con el rigor, la curiosidad y la humildad ante los datos que él mismo empleó para atrapar átomos en el frío más extremo y, después, para intentar transformar una de las instituciones más tradicionales: el aula universitaria. El éxito final de esta segunda revolución, aún inconclusa, podría determinar cómo la sociedad del futuro enfrenta los problemas complejos que la ciencia misma ayuda a crear y a resolver.

Robin Warren: Pionier der medizinischen Forschung

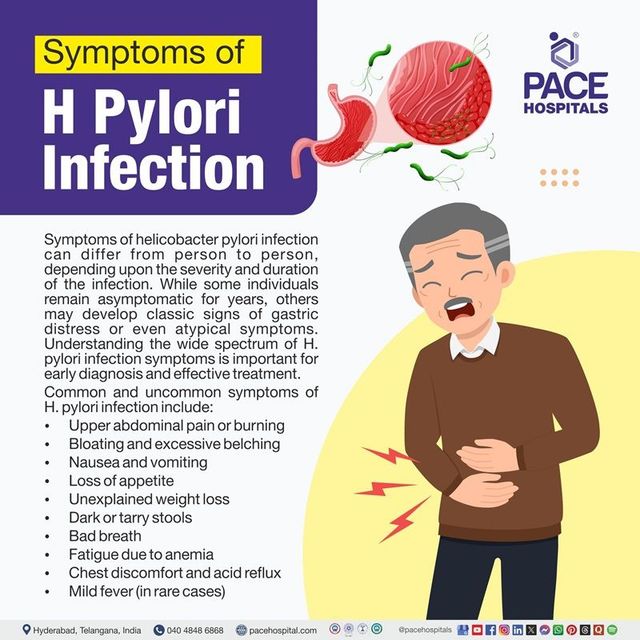

Der australische Pathologe John Robin Warren veränderte mit einer bahnbrechenden Entdeckung die Welt der Gastroenterologie für immer. Seine Arbeit, die zur Identifizierung des Bakteriums Helicobacter pylori führte, beendete ein medizinisches Dogma und revolutionierte die Behandlung von Magengeschwüren. Für diese Leistung erhielt er 2005, gemeinsam mit Barry J. Marshall, den Nobelpreis für Physiologie oder Medizin.

Warren, der am 23. Juli 2024 im Alter von 87 Jahren in Perth verstarb, gilt als einer der großen klinischen Beobachter des 20. Jahrhunderts. Seine Karriere, die sich über Jahrzehnte am Royal Perth Hospital erstreckte, steht beispielhaft für die Kraft der histologischen Forschung und des genauen Hinsehens. Dieser Artikel beleuchtet das Leben und das wegweisende Vermächtnis dieses medizinischen Pioniers.

Frühes Leben und medizinische Laufbahn

John Robin Warren wurde am 11. Juni 1937 in Adelaide, Australien, geboren. Sein Weg in die Medizin führte ihn an die University of Adelaide, wo er sein Studium 1961 erfolgreich abschloss. Die Wahl der Pathologie als Fachgebiet erwies sich als entscheidend für seine spätere Entdeckung.

Den Großteil seiner beruflichen Tätigkeit verbrachte Warren als leitender Pathologe am Royal Perth Hospital. Hier entwickelte er seine Expertise in der mikroskopischen Untersuchung von Gewebeproben. Seine akribische Arbeitsweise und sein Interesse an scheinbar unbedeutenden Details prägten seinen Forschungsstil und sollten schließlich zu einem Paradigmenwechsel führen.

Bis zu seinem Ruhestand im Jahr 1999 blieb Warren dieser Institution verbunden. Seine Arbeit war stets von einem tiefen Verständnis für die klinischen Implikationen der Pathologie geprägt. Dieser klinisch-pathologische Ansatz wurde zum Fundament seiner historischen Entdeckung.

Die historische Entdeckung von Helicobacter pylori

Ende der 1970er Jahre stieß Warren bei der Untersuchung von Magenbiopsien unter dem Mikroskop immer wieder auf ein ungewöhnliches Phänomen. In den Proben von Patienten mit Gastritis oder Magengeschwüren entdeckte er kurvige Bakterien, die sich in der Schleimhautschicht des Magens ansiedelten.

Ein Dogma gerät ins Wanken

Bis zu diesem Zeitpunkt war die vorherrschende medizinische Lehrmeinung, dass der menschliche Magen aufgrund der starken Säure steril sei. Die Ursachen für peptische Ulzera (Magen- und Zwölffingerdarmgeschwüre) wurden hauptsächlich in Faktoren wie Stress, Übersäuerung oder einer genetischen Veranlagung gesehen. Warrens Beobachtung stellte dieses langjährige Dogma fundamental in Frage.

Die Kombination aus histologischer Beobachtung, Kultivierungstechnik und späteren klinischen Studien führte zur breiten Akzeptanz der neuen Theorie.

Warrens Entdeckung war zunächst ein solitärer Befund. Die entscheidende Wende kam durch die Zusammenarbeit mit dem jungen Assistenzarzt Barry J. Marshall. Marshall gelang es, die von Warren beschriebenen Bakterien zu kultivieren, was den wissenschaftlichen Nachweis erheblich vorantrieb. Gemeinsam entwickelten sie die Hypothese, dass dieses Bakterium, später Helicobacter pylori genannt, die primäre Ursache für Gastritis und viele Geschwüre ist.

Der Weg zum Nobelpreis 2005

Die Widerstände gegen die neue Theorie waren anfangs immens. Um die Koch'schen Postulate zu erfüllen und einen kausalen Zusammenhang zu beweisen, unternahm Barry Marshall 1984 einen spektakulären Selbstversuch. Die darauf folgende Erkrankung und erfolgreiche Behandlung stärkte die Evidenz entscheidend.

In den folgenden Jahren untermauerten zahlreiche internationale Studien die Verbindung zwischen H. pylori und peptischen Ulzera. Die Entwicklung zuverlässiger diagnostischer Tests, wie des Urease-Atemtests, trug maßgeblich zur Verbreitung der neuen Erkenntnisse in der klinischen Praxis bei. Die bahnbrechende Arbeit von Warren und Marshall führte zu einem völlig neuen Therapieansatz.

Für die Entdeckung des Bakteriums Helicobacter pylori und seine Rolle bei der Entstehung von Gastritis und Magengeschwüren wurden J. Robin Warren und Barry J. Marshall im Jahr 2005 mit dem Nobelpreis für Physiologie oder Medizin ausgezeichnet. Das Nobelkomitee würdigte damit eine Entdeckung, die die Lebensqualität von Millionen Patienten weltweit verbesserte.

Klinische Folgen und ein neues Therapiezeitalter

Die Anerkennung der bakteriellen Ursache führte zu einem radikalen Wandel in der Behandlung von Magen- und Zwölffingerdarmgeschwüren. Anstelle von rein säurehemmenden Medikamenten oder chirurgischen Eingriffen trat nun eine Eradikationstherapie mit Antibiotika in Kombination mit Protonenpumpenhemmern.

- Reduktion von Rezidiven: Die antibiotische Behandlung von H. pylori führte zu einer dramatischen Verringerung der Wiederauftrittsrate von Geschwüren.

- Rückgang der Operationen: Weltweit ging die Zahl der notwendigen chirurgischen Eingriffe zur Ulkusbehandlung stark zurück.

- Neue Diagnostik: Einfache nicht-invasive Tests, wie der Atemtest, wurden Standard in der Diagnostik.

Warrens initiale histologische Beobachtung legte somit den Grundstein für eine der bedeutendsten Veränderungen in der klinischen Medizin des späten 20. Jahrhunderts. Aus einem chronischen, oft rezidivierenden Leiden wurde eine in der Regel heilbare Infektionskrankheit.

Das Vermächtnis eines klinischen Beobachters

Robin Warrens Vermächtnis geht weit über den Nobelpreis hinaus. Er verkörperte den Typus des neugierigen, detailversessenen Wissenschaftlers, der einer Beobachtung so lange nachgeht, bis sie erklärt ist. Seine Arbeit betonte stets die fundamentale Bedeutung der Pathologie als Brücke zwischen Grundlagenforschung und patientennaher Anwendung.

Sein Ansatz, "genau hinzusehen", wie es in Nachrufen oft heißt, führte nicht nur zu einer medizinischen Revolution, sondern auch zu einem Umdenken in der Ausbildung. Kliniker weltweit wurden für die Bedeutung mikroskopischer Diagnostik und eine enge Zusammenarbeit mit Pathologen sensibilisiert. Warren bewies, dass eine einzelne, sorgfältige Beobachtung ein ganzes medizinisches Fachgebiet auf den Kopf stellen kann.

Dieses Vermächtnis ist in jedem Labor und bei jeder Magenspiegelung präsent, bei der heute aktiv nach Helicobacter pylori gesucht wird. Warren hat gezeigt, dass wissenschaftlicher Fortschritt oft mit dem Hinterfragen von scheinbar feststehenden Tatsachen beginnt.

Rolle in der Krebsprävention und globale Auswirkungen

Die Entdeckung von Helicobacter pylori hatte nicht nur Auswirkungen auf die Behandlung von Geschwüren, sondern eröffnete auch völlig neue Perspektiven in der Krebsprävention. Epidemiologische Studien zeigten einen klaren Zusammenhang zwischen einer chronischen H. pylori-Infektion und einem erhöhten Risiko für bestimmte Magenkrebsarten, insbesondere das Magenkarzinom.

Neue Strategien in der Onkologie

Diese Erkenntnis führte zu einem strategischen Umdenken. Die Eradikation von H. pylori wird seither nicht mehr nur als Therapie für Geschwüre, sondern zunehmend auch als potenzielle präventive Maßnahme in Betracht gezogen. In Hochrisikopopulationen, wie in Regionen mit hoher Magenkrebsinzidenz, kann die frühzeitige Behandlung der Infektion das Krebsrisiko signifikant senken.

Internationale Leitlinien, beispielsweise der Weltgesundheitsorganisation (WHO), klassifizieren H. pylori mittlerweile als Karzinogen der Gruppe 1. Damit ist das Bakterium eindeutig als krebserregend für den Menschen eingestuft. Diese Einstufung unterstreicht die weitreichende Bedeutung von Warrens und Marshalls Entdeckung für die öffentliche Gesundheit.

Die globale Krankheitslast durch Magenkrebs konnte durch diesen neuen Ansatz bereits positiv beeinflusst werden. Die gezielte Bekämpfung eines bakteriellen Erregers zur Krebsprävention war vor Warrens Arbeit ein kaum vorstellbares Konzept und markiert einen Meilenstein in der präventiven Medizin.

Aktuelle Herausforderungen: Antibiotikaresistenzen

Trotz des großen Erfolgs der Eradikationstherapie sieht sich die moderne Medizin heute mit einer wachsenden Herausforderung konfrontiert: Antibiotikaresistenzen. Helicobacter pylori-Stämme entwickeln zunehmend Resistenzen gegen Standardantibiotika wie Clarithromycin und Metronidazol.

- Regionale Variation: Die Resistenzraten variieren global stark und erfordern lokale Anpassungen der Therapieprotokolle.

- Therapieversagen: Resistenzen führen zu einer erhöhten Rate an Therapieversagen, was die Behandlung komplexer und kostenintensiver macht.

- Leitlinien-Anpassung: Fachgesellschaften passen ihre Empfehlungen kontinuierlich an, basierend auf aktuellen Resistenzdaten, und empfehlen zunehmend Kombinationstherapien oder Resistenztestungen.

Diese Entwicklung unterstreicht die Dynamik im Feld, das Warren mitbegründet hat. Die Forschung konzentriert sich nun auf die Entwicklung neuer Therapieregimes, die auch gegen resistente Stämme wirksam sind. Es ist ein fortlaufender Kampf, der die anhaltende Relevanz der H. pylori-Forschung beweist.

Die gezielte Bekämpfung eines bakteriellen Erregers zur Krebsprävention war vor Warrens Arbeit ein kaum vorstellbares Konzept.

Auszeichnungen und späte Würdigungen

Neben dem Nobelpreis erhielten J. Robin Warren und Barry J. Marshall zahlreiche weitere prestigeträchtige Auszeichnungen, die ihre Arbeit schon vor der breiten Nobelpreis-Würdigung anerkannten. Diese Preise spiegelten die wachsende Akzeptanz und die revolutionäre Bedeutung ihrer Entdeckung in der Fachwelt wider.

Bedeutende Preise im Überblick

Bereits 1994 wurden die beiden Forscher mit dem Warren Alpert Foundation Prize ausgezeichnet. 1997 folgte einer der renommiertesten deutschen Forschungspreise, der Paul-Ehrlich-und-Ludwig-Darmstaedter-Preis. Diese Ehrungen kamen zu einem Zeitpunkt, als sich die neue Theorie international durchgesetzt hatte und ihren Siegeszug in den klinischen Leitlinien antrat.

Die höchste australische zivile Ehrung erhielt Warren im Jahr 2007, als er zum Companion of the Order of Australia ernannt wurde. Diese Auszeichnung würdigte nicht nur seinen wissenschaftlichen Dienst, sondern seinen herausragenden Beitrag zum Wohlstand der australischen Nation und der gesamten Menschheit.

Jede dieser Ehrungen markiert einen Schritt auf dem Weg von einer umstrittenen Hypothese hin zu einem unumstößlichen Bestandteil des medizinischen Wissens. Sie zeichnen die Karriere eines Mannes nach, der unbeirrt an seiner Beobachtung festhielt.

Die Methodik: Vom Mikroskop zur klinischen Studie

Warrens Erfolg basierte auf einer konsequenten und methodisch vielschichtigen Herangehensweise. Sie begann am Mikroskop, fand aber erst durch die Integration weiterer Disziplinen ihren Weg in die weltweite klinische Praxis. Dieser methodische Mix war entscheidend für den letztendlichen Durchbruch.

Die ersten Schritte waren rein histologischer Natur. Warren dokumentierte systematisch das Vorkommen der unbekannten Bakterien in Gewebeproben und korrelierte seinen Befund mit dem klinischen Zustand der Patienten. Dieser pathologische Ansatz lieferte die initiale Hypothese.

Der nächste, entscheidende Schritt war die Kultivierung des Erregers durch Barry Marshall. Erst mit einem reinen Bakterienstamm konnten experimentelle und klinische Studien durchgeführt werden. Die Kombination aus Pathologie und Mikrobiologie schuf eine solide wissenschaftliche Basis.

Den abschließenden Beweis erbrachten dann klinische Interventionsstudien. Sie zeigten, dass die antibiotische Eradikation von H. pylori tatsächlich zur Abheilung von Geschwüren und zur dauerhaften Verhinderung von Rezidiven führte. Dieser Dreiklang aus Beobachtung, Experiment und klinischer Bestätigung ist bis heute ein Musterbeispiel für erfolgreiche medizinische Forschung.

Tod und weltweite Reaktionen

J. Robin Warren verstarb am 23. Juli 2024 friedlich in Perth im hohen Alter von 87 Jahren. Die Nachricht von seinem Tod löste weltweit eine Welle der Würdigung und des Gedenkens aus. Fachgesellschaften, Universitäten und ehemalige Kollegen betonten unisono seinen bescheidenen Charakter und seinen unerschütterlichen Forschungswillen.

Medien auf der ganzen Welt hoben die globale Bedeutung seiner Entdeckung hervor. Sie betonten, wie seine Arbeit direkt dazu beigetragen hat, menschliches Leid zu lindern und lebensverändernde Behandlungen zu etablieren. Sein Tod markierte das Ende einer Ära, aber die Prinzipien seiner Forschung bleiben lebendig.

Barry J. Marshall, sein langjähriger Partner und Mit-Nobelpreisträger, würdigte Warren als ruhigen und präzisen Denker, dessen Entdeckung ohne seine akribische Arbeit am Mikroskop niemals möglich gewesen wäre. Diese Partnerschaft zwischen dem geduldigen Pathologen und dem draufgängerischen Kliniker wurde als ideale Symbiose für den wissenschaftlichen Fortschritt beschrieben.

Die Lehren aus Warrens Karriere für junge Forscher

Die Laufbahn von Robin Warren bietet zahlreiche wertvolle Lektionen für angehende Wissenschaftler und Ärzte. Sie ist ein Lehrstück darüber, wie wichtige Entdeckungen oft jenseits der ausgetretenen Pfade gemacht werden und welche persönlichen Eigenschaften diesen Erfolg ermöglichen.

Die Kraft der Beharrlichkeit

Warrens Weg war nicht einfach. Seine Beobachtungen wurden zunächst von vielen etablierten Kollegen und Fachzeitschriften angezweifelt oder ignoriert. Seine Beharrlichkeit und sein Glaube an die eigene sorgfältige Arbeit waren entscheidend, um diese Phase des Widerstands zu überstehen. Dies unterstreicht, wie wichtig intellektuelle Unabhängigkeit in der Forschung ist.

Eine weitere zentrale Lehre ist der Wert der klinischen Beobachtung. In einem Zeitalter hochtechnisierter Medizin demonstrierte Warren, dass das geschulte Auge und die Frage nach dem "Warum" immer noch zu den mächtigsten Werkzeugen eines Arztes gehören. Seine Arbeit begann nicht mit einem teuren Gerät, sondern mit Neugier und einem Mikroskop.

Schließlich zeigt seine Kooperation mit Marshall die Bedeutung interdisziplinärer Zusammenarbeit. Warrens pathologischer Befund allein hätte nicht ausgereicht; Marshalls klinische und mikrobiologische Expertise war nötig, um die Theorie zu beweisen. Erfolg entsteht oft an den Schnittstellen der Fächer.

Helicobacter pylori heute: Stand der Forschung 2025

Die Forschung zu Helicobacter pylori ist auch fast 50 Jahre nach seiner Entdeckung hoch dynamisch. Die aktuellen Schwerpunkte spiegeln sowohl die Erfolge als auch die neuen Herausforderungen wider, die aus der bahnbrechenden Arbeit von Warren und Marshall erwachsen sind.

- Präzisionsmedizin: Die Behandlung wird zunehmend individualisiert, basierend auf lokalen Resistenzmustern und genetischen Markern des Bakteriums, um die Eradikationsraten weiter zu steigern.

- Impfstoffentwicklung: Obwohl immer noch herausfordernd, bleibt die Entwicklung eines prophylaktischen oder therapeutischen Impfstoffs ein langfristiges Ziel, um die Infektion und ihre Folgen grundlegend zu bekämpfen.

- Mikrobiom-Interaktion: Forscher untersuchen intensiv die Wechselwirkung von H. pylori mit dem restlichen Magen- und Darmmikrobiom und deren Einfluss auf die Krankheitsentstehung.

- Früherkennungsstrategien: In Hochrisikoregionen werden Programme zur gezielten Früherkennung und Eradikation von H. pylori als Teil von Magenkrebs-Präventionsprogrammen evaluiert und implementiert.

Seine Arbeit begann nicht mit einem teuren Gerät, sondern mit Neugier und einem Mikroskop.

Damit bleibt H. pylori ein faszinierender Modellerreger, an dem grundlegende Prinzipien der chronischen Infektion, Krebsentstehung und Wirt-Pathogen-Interaktion erforscht werden. Warrens Erbe lebt in jedem dieser Forschungsprojekte fort.

Fazit: Ein Pionier, der die Medizin neu definierte

Robin Warrens Lebenswerk steht für einen der größten Paradigmenwechsel in der Medizingeschichte des 20. Jahrhunderts. Er verwandelte die Sichtweise auf die Volkskrankheit "Maggengeschwür" von einem lebensstilbedingten, chronischen Leiden in eine heilbare Infektionskrankheit. Dieser Perspektivwechsel rettete unzähligen Patienten invasive Operationen und brachte ihnen nachhaltige Heilung.

Seine Karriere demonstriert die transformative Macht der Grundlagenforschung in der Pathologie. Sie beweist, dass die scheinbar stille Arbeit am Mikroskop die Kraft hat, klinische Leitlinien weltweit umzuschreiben und neue Standards der Versorgung zu setzen. Warren war kein lauter Revolutionär, sondern ein stiller Beobachter, dessen Beobachtungen die Welt lauter erschallen ließen.

Das anhaltende Vermächtnis

Das Vermächtnis von J. Robin Warren ist in jeder erfolgreichen Eradikationstherapie, in jedem vermiedenen chirurgischen Eingriff und in jeder präventiven Magenkrebs-Beratung greifbar. Er hat gezeigt, dass wissenschaftlicher Fortschritt Geduld, Genauigkeit und den Mut erfordert, etablierte Wahrheiten in Frage zu stellen.

Seine Geschichte ist eine zeitlose Erinnerung daran, dass große Entdeckungen manchmal direkt vor unseren Augen liegen – wir müssen nur, wie Robin Warren, genau hinsehen. Sein Beitrag zur Menschheit wird weiterleben, solange Ärzte Magengeschwüre mit einer einfachen Antibiotikakur heilen können. In der Geschichte der Medizin bleibt sein Name für immer mit der Überwindung eines Dogmas und dem Beginn einer neuen Ära der gastroenterologischen Heilkunst verbunden.

Jacques Monod: Pionier der Molekularbiologie und Nobelpreisträger

Jacques Lucien Monod war ein französischer Biochemiker, dessen bahnbrechende Arbeit die Molekularbiologie grundlegend prägte. Für seine Entdeckungen zur genetischen Kontrolle von Enzymen erhielt er 1965 den Nobelpreis für Physiologie oder Medizin. Seine Modelle, wie das berühmte Operon-Modell, gelten noch heute als Meilensteine der modernen Genetik.

Frühes Leben und akademische Ausbildung

Jacques Monod wurde am 9. Februar 1910 in Paris geboren. Schon früh zeigte sich sein breites Interesse für Naturwissenschaften und Musik. Er begann sein Studium an der Universität Paris, wo er sich zunächst der Zoologie widmete. Seine wissenschaftliche Laufbahn wurde durch den Zweiten Weltkrieg unterbrochen, doch er promovierte dennoch im Jahr 1941.

Der Weg zum Pasteur-Institut

Ein entscheidender Wendepunkt war 1941 der Eintritt von Jacques Monod in das berühmte Pasteur-Institut in Paris. Hier fand er das ideale Umfeld für seine bahnbrechende Forschung. Ab 1945 übernahm er die Leitung der Abteilung für Mikroben-Physiologie und legte damit den Grundstein für seine späteren Nobelpreis-würdigen Entdeckungen.

Am Pasteur-Institut konzentrierte er seine Arbeit auf den Stoffwechsel von Bakterien, insbesondere von Escherichia coli. Diese Fokussierung erwies sich als äußerst fruchtbar und führte zur Entwicklung der Monod-Kinetik im Jahr 1949.

Die Monod-Kinetik: Ein Fundament der Biotechnologie

Im Jahr 1949 veröffentlichte Jacques Monod ein mathematisches Modell, das das Wachstum von Bakterienkulturen in Abhängigkeit von der Nährstoffkonzentration beschreibt. Dieses Modell, bekannt als Monod-Kinetik, wurde zu einem grundlegenden Werkzeug in der Mikrobiologie und Biotechnologie.

Die Formel erlaubt es, das mikrobielle Wachstum präzise vorherzusagen und zu steuern. Bis heute ist sie unverzichtbar in Bereichen wie der Fermentationstechnik, der Abwasserbehandlung und der industriellen Produktion von Antibiotika.

Die Monod-Kinetik beschreibt, wie die Wachstumsrate von Mikroorganismen von der Konzentration eines limitierenden Substrats abhängt – ein Prinzip, das in jedem biotechnologischen Labor Anwendung findet.

Entdeckung wichtiger Enzyme

Parallel zu seinen kinetischen Studien entdeckte und charakterisierte Monod mehrere Schlüsselenzyme. Diese Entdeckungen waren direkte Beweise für seine theoretischen Überlegungen zur Genregulation.

- Amylo-Maltase (1949): Ein Enzym, das am Maltose-Stoffwechsel beteiligt ist.

- Galactosid-Permease (1956): Ein Transporterprotein, das Lactose in die Bakterienzelle schleust.

- Galactosid-Transacetylase (1959): Ein Enzym mit Funktion im Lactose-Abbauweg.

Die Arbeit an diesen Enzymen führte Monod und seinen Kollegen François Jacob direkt zur Formulierung ihres revolutionären Operon-Modells.

Das Operon-Modell: Eine Revolution in der Genetik

Die gemeinsame Arbeit von Jacques Monod und François Jacob am Pasteur-Institut gipfelte in den frühen 1960er Jahren in der Entwicklung des Operon-Modells, auch Jacob-Monod-Modell genannt. Diese Theorie erklärte erstmals, wie Gene in Bakterien koordiniert reguliert und ein- oder ausgeschaltet werden.

Die Rolle der messenger-RNA

Ein zentraler Bestandteil des Modells war die Vorhersage der Existenz einer kurzlebigen Boten-RNA, der messenger-RNA (mRNA). Monod und Jacob postulierten, dass die genetische Information von der DNA auf diese mRNA kopiert wird, welche dann als Bauplan für die Proteinherstellung dient. Diese Vorhersage wurde kurz darauf experimentell bestätigt.

Die Entdeckung der mRNA war ein Schlüsselmoment für das Verständnis des zentralen Dogmas der Molekularbiologie und ist heute Grundlage für Technologien wie die mRNA-Impfstoffe.

Aufbau und Funktion des Lactose-Operons

Am Beispiel des Lactose-Operons in E. coli zeigten sie, dass strukturelle Gene, ein Operator und ein Promotor als eine funktionelle Einheit agieren. Ein Regulatorgen kodiert für ein Repressorprotein, das den Operator blockieren kann.

- Ohne Lactose bindet der Repressor am Operator und verhindert die Genexpression.

- Ist Lactose vorhanden, bindet sie an den Repressor, ändert dessen Form und löst ihn vom Operator.

- Die RNA-Polymerase kann nun die strukturellen Gene ablesen, und die Enzyme für den Lactoseabbau werden produziert.

Dieses elegante Modell der Genregulation erklärt, wie Zellen Energie sparen und sich flexibel an Umweltveränderungen anpassen können.

Die höchste wissenschaftliche Anerkennung: Der Nobelpreis 1965

Für diese bahnbrechenden Erkenntnisse wurde Jacques Monod zusammen mit François Jacob und André Lwoff im Jahr 1965 der Nobelpreis für Physiologie oder Medizin verliehen. Die offizielle Begründung des Nobelkomitees lautete: „für ihre Entdeckungen auf dem Gebiet der genetischen Kontrolle der Synthese von Enzymen und Viren“.

Die Verleihung dieses Preises markierte nicht nur den Höhepunkt von Monods Karriere, sondern unterstrich auch die zentrale Rolle des Pasteur-Instituts als globales Epizentrum der molekularbiologischen Forschung. Seine Arbeit hatte gezeigt, dass grundlegende Lebensprozesse auf molekularer Ebene verstanden und mathematisch beschrieben werden können.

Die Entdeckung des Operon-Modells war ein Paradigmenwechsel. Sie zeigte, dass Gene nicht einfach autonom funktionieren, sondern in komplexen Netzwerken reguliert werden.

Im nächsten Teil dieser Artikelserie vertiefen wir Monods Beitrag zur Allosterie-Theorie, seine philosophischen Schriften und sein bleibendes Vermächtnis für die moderne Wissenschaft.

Luis Alvarez: Nobel Laureate and Physics Pioneer

Luis Walter Alvarez (1911–1988) was an American experimental physicist whose groundbreaking work revolutionized particle physics. Known for his hydrogen bubble chamber invention, Alvarez's contributions earned him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1968. His legacy spans nuclear research, radar technology, and even the theory behind dinosaur extinction.

Early Life and Education

Born on June 13, 1911, in San Francisco, California, Alvarez was the son of physician Walter C. Alvarez and Harriet Smyth. His academic journey began at the University of Chicago, where he earned:

- Bachelor of Science (B.S.) in 1932

- Master of Science (M.S.) in 1934

- Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in 1936

After completing his studies, Alvarez joined the faculty at the University of California, Berkeley in 1936, where he would spend most of his career.

Major Scientific Contributions

Pioneering the Hydrogen Bubble Chamber

Alvarez's most famous invention, the hydrogen bubble chamber, transformed particle physics. This device allowed scientists to observe the tracks of subatomic particles, leading to the discovery of numerous resonance particles. Key features included:

- A 7-foot-long chamber filled with liquid hydrogen

- Millions of particle interaction photos captured and analyzed

- Discovery of over 70 new particles

His work earned him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1968 for "decisive contributions to elementary particle physics."

World War II and Radar Technology

During World War II, Alvarez contributed to critical military technologies at the MIT Radiation Laboratory (1940–1943), including:

- Development of radar systems for bombing accuracy

- Microwave beacons and ground-controlled landing systems

- Work on the Manhattan Project (1943–1945), where he helped design the implosion mechanism for the atomic bomb

His innovations in radar technology significantly improved Allied bombing precision.

Inventions and Discoveries

Key Innovations Beyond Particle Physics

Alvarez's inventive spirit extended beyond particle physics. Notable contributions include:

- The first proton linear accelerator (1947), a foundational tool for nuclear research

- Development of the charge exchange acceleration concept, leading to the Tandem Van de Graaff generator

- Early work on K-electron capture (1937–1938) and the measurement of the neutron's magnetic moment with Felix Bloch (1939)

The Dinosaur Extinction Theory

In 1980, Alvarez and his son, geologist Walter Alvarez, proposed a revolutionary theory: that a massive asteroid impact caused the extinction of the dinosaurs. Their evidence included:

- A global layer of iridium, a rare element abundant in asteroids

- The later discovery of the Chicxulub crater in Mexico, confirming their hypothesis

This theory reshaped paleontology and remains a cornerstone of modern geology.

Legacy and Honors

Alvarez's impact on science and technology earned him numerous accolades, including:

- Induction into the National Inventors Hall of Fame

- Membership on the President's Science Advisory Committee (1971–1972)

- Recognition as a brilliant experimental physicist in Hispanic Heritage contexts

His work continues to influence modern particle detectors, such as those used at CERN, and his asteroid impact theory remains a foundational concept in geology.

Conclusion (Part 1)

Luis Alvarez's contributions to physics, technology, and geology have left an indelible mark on science. From his Nobel Prize-winning bubble chamber to his groundbreaking dinosaur extinction theory, his legacy endures in research and innovation worldwide. In the next section, we will explore his later career, collaborations, and the lasting impact of his discoveries.

Collaborations and Major Projects

Throughout his career, Luis Alvarez collaborated with leading scientists, blending experimental physics with innovative engineering. His partnerships advanced nuclear research, radar technology, and particle detection.

Work with Ernest Lawrence and the Radiation Lab

At UC Berkeley's Radiation Lab, Alvarez worked under Ernest Lawrence, a pioneer in particle accelerators. Together, they developed:

- The cyclotron, an early particle accelerator

- Techniques for high-energy physics experiments

- Advancements in cosmic ray research, including the discovery of the "East-West effect"

These collaborations laid the groundwork for Alvarez's later achievements in particle physics.

Manhattan Project Contributions

During World War II, Alvarez joined the Manhattan Project, working at Chicago Pile-2 and Los Alamos. His key contributions included:

- Designing the implosion mechanism for the atomic bomb

- Developing a device to measure the Hiroshima blast's energy

- Improving reactor detection methods for military applications

His work was critical to the project's success and post-war nuclear research.

Later Career and Impact on Modern Physics

After World War II, Alvarez returned to UC Berkeley, where he led groundbreaking projects in particle physics and beyond.

The Bevatron and High-Energy Physics

Alvarez played a pivotal role in the development of the Bevatron, a powerful particle accelerator with:

- 6 billion electron volts (6 GeV) of energy

- Capability to produce antiprotons and other exotic particles

- Applications in nuclear theory and particle discovery

This machine enabled experiments that deepened our understanding of subatomic particles.

Cosmic Ray Research and Balloon Experiments

In his later years, Alvarez shifted focus to cosmic ray studies, conducting experiments using high-altitude balloons. His research included:

- Measuring cosmic ray fluxes at different altitudes

- Investigating high-energy particle interactions in the atmosphere

- Contributing to early space physics research

These studies bridged particle physics and astrophysics, influencing future space missions.

Alvarez’s Influence on Technology and Industry

Beyond academia, Alvarez's inventions had practical applications in industry and defense.

Radar and Aviation Advancements

His wartime radar developments had lasting impacts on aviation and navigation:

- Ground-controlled landing systems for aircraft

- Microwave beacons for precision bombing

- Improvements in air traffic control technology

These innovations enhanced safety and efficiency in both military and civilian aviation.

Medical and Industrial Applications

Alvarez's work also extended to medical and industrial fields:

- Development of radio distance/direction indicators

- Contributions to nuclear medicine through isotope research

- Advancements in industrial radiography for material testing

His inventions demonstrated the broad applicability of physics in solving real-world problems.

Personal Life and Legacy

Outside the lab, Alvarez was known for his curiosity, creativity, and dedication to science.

Family and Personal Interests

Alvarez married Geraldine Smithwick in 1936, and they had two children, Walter and Jean. His son, Walter, became a renowned geologist and collaborator on the dinosaur extinction theory. Alvarez's hobbies included:

- Amateur radio operation

- Photography, which aided his scientific documentation

- Exploring archaeology and ancient civilizations

His diverse interests reflected his interdisciplinary approach to science.

Honors and Recognition

Alvarez received numerous awards, including:

- The Nobel Prize in Physics (1968)

- Induction into the National Inventors Hall of Fame

- Membership in the National Academy of Sciences

His legacy endures in modern physics, from CERN's particle detectors to ongoing research on asteroid impacts.

Conclusion (Part 2)

Luis Alvarez's career was marked by innovation, collaboration, and a relentless pursuit of discovery. His work in particle physics, radar technology, and geological theory reshaped multiple fields. In the final section, we will explore his lasting influence on science and the continued relevance of his theories today.

Alvarez’s Enduring Impact on Science

The legacy of Luis Alvarez extends far beyond his lifetime, influencing modern physics, technology, and even our understanding of Earth's history. His innovations continue to shape research and industry today.

Modern Particle Physics and CERN

Alvarez’s hydrogen bubble chamber revolutionized particle detection, paving the way for advanced technologies used at institutions like CERN. Key contributions include:

- Inspiration for digital particle detectors in modern accelerators

- Development of automated data analysis techniques still used today

- Discovery of resonance particles, which expanded the Standard Model of physics

His methods remain foundational in experiments at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC).

The Alvarez Hypothesis and Geological Research

The asteroid impact theory proposed by Alvarez and his son Walter transformed paleontology. Recent developments include:

- Confirmation of the Chicxulub crater in the 1990s

- Ongoing drilling expeditions (2020s) studying the impact’s effects

- Expanded research on mass extinction events in Earth’s history

This theory remains a cornerstone of impact geology and planetary science.

Alvarez’s Influence on Technology and Innovation

Beyond theoretical science, Alvarez’s inventions had practical applications that persist in modern technology.

Advancements in Accelerator Technology

His work on particle accelerators led to breakthroughs such as:

- The Tandem Van de Graaff generator, used in nuclear research

- Early proton linear accelerators, precursors to today’s medical and industrial machines

- Improvements in beam focusing and particle collision techniques

These innovations are critical in fields like cancer treatment and materials science.

Radar and Aviation Legacy

Alvarez’s wartime radar developments had lasting effects on aviation and defense:

- Ground-controlled landing systems now standard in airports worldwide

- Precision navigation tools for military and commercial aircraft

- Foundational work for modern air traffic control

His contributions enhanced safety and efficiency in global aviation.

Alvarez’s Role in Education and Mentorship

As a professor at UC Berkeley, Alvarez mentored generations of physicists, fostering a culture of innovation.

Training Future Scientists

His leadership in the Radiation Lab and Bevatron project involved:

- Supervising dozens of graduate students who became leading researchers

- Collaborating with hundreds of engineers and technicians

- Establishing interdisciplinary research teams in particle physics

Many of his students went on to win prestigious awards, including Nobel Prizes.

Public Engagement and Science Advocacy

Alvarez was a vocal advocate for science education and policy:

- Served on the President’s Science Advisory Committee (1971–1972)

- Promoted STEM education in schools and universities

- Encouraged public understanding of complex scientific concepts

His efforts helped bridge the gap between academia and society.

Challenges and Controversies

Like many pioneers, Alvarez faced skepticism and debate over his theories.

Initial Skepticism of the Impact Theory

The dinosaur extinction hypothesis was initially met with resistance:

- Critics argued for volcanic activity as the primary cause

- Debates persisted until the Chicxulub crater was discovered

- Modern consensus now supports the asteroid impact model

This controversy highlights the importance of evidence-based science.

Ethical Debates in Nuclear Research

Alvarez’s work on the Manhattan Project raised ethical questions:

- Concerns about the moral implications of nuclear weapons

- Debates on the responsibility of scientists in military applications

- Discussions on nuclear disarmament and global security

These issues remain relevant in today’s scientific community.

Final Thoughts: The Legacy of Luis Alvarez

Luis Alvarez’s life and work exemplify the power of curiosity, innovation, and collaboration. His contributions to particle physics, technology, and geological theory have left an indelible mark on science.

Key Takeaways

- Nobel Prize in Physics (1968) for the hydrogen bubble chamber

- Pioneering the asteroid impact theory for dinosaur extinction

- Inventions that advanced radar technology and particle accelerators

- Mentorship of future scientists and advocacy for STEM education

A Lasting Influence

From CERN’s particle detectors to ongoing research on mass extinctions, Alvarez’s ideas continue to inspire. His interdisciplinary approach reminds us that science is not just about discovery—it’s about solving real-world problems and expanding human knowledge. As we look to the future, his legacy serves as a testament to the enduring impact of bold, innovative thinking.

In the words of Alvarez himself:

"The most important thing in science is not so much to obtain new facts as to discover new ways of thinking about them."

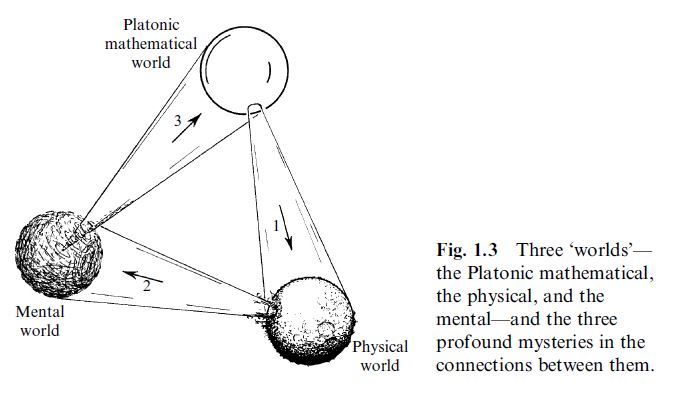

Sir Roger Penrose: Nobel Laureate and Revolutionary Physicist

Sir Roger Penrose, born August 8, 1931, is a pioneering English mathematician, mathematical physicist, and philosopher of science. In 2020, he earned the Nobel Prize in Physics for proving black hole formation as an inevitable outcome of general relativity. At 94 years old, Penrose remains a leading voice in cosmology, quantum gravity, and the nature of consciousness.

Groundbreaking Contributions to Physics

Penrose's work has reshaped our understanding of the universe. His theories combine deep mathematical insight with bold physical imagination.

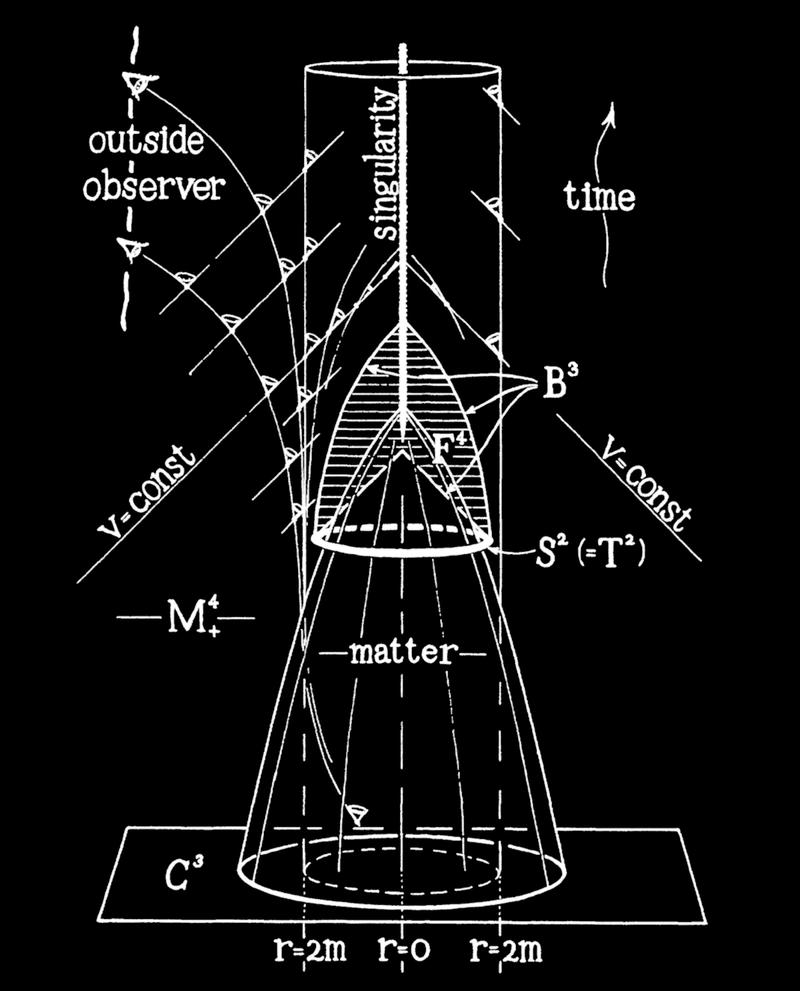

Black Hole Formation and Singularity Theorems

In the 1960s, Penrose revolutionized black hole physics. Working with Stephen Hawking, he developed singularity theorems proving that singularities—points of infinite density—must form in gravitational collapse.

"Spacetime singularities are not artifacts of idealized models but robust predictions of general relativity." — Roger Penrose