Virgil: The Mastermind of Roman Literature

Introduction: The Life and Legacy of Virgil

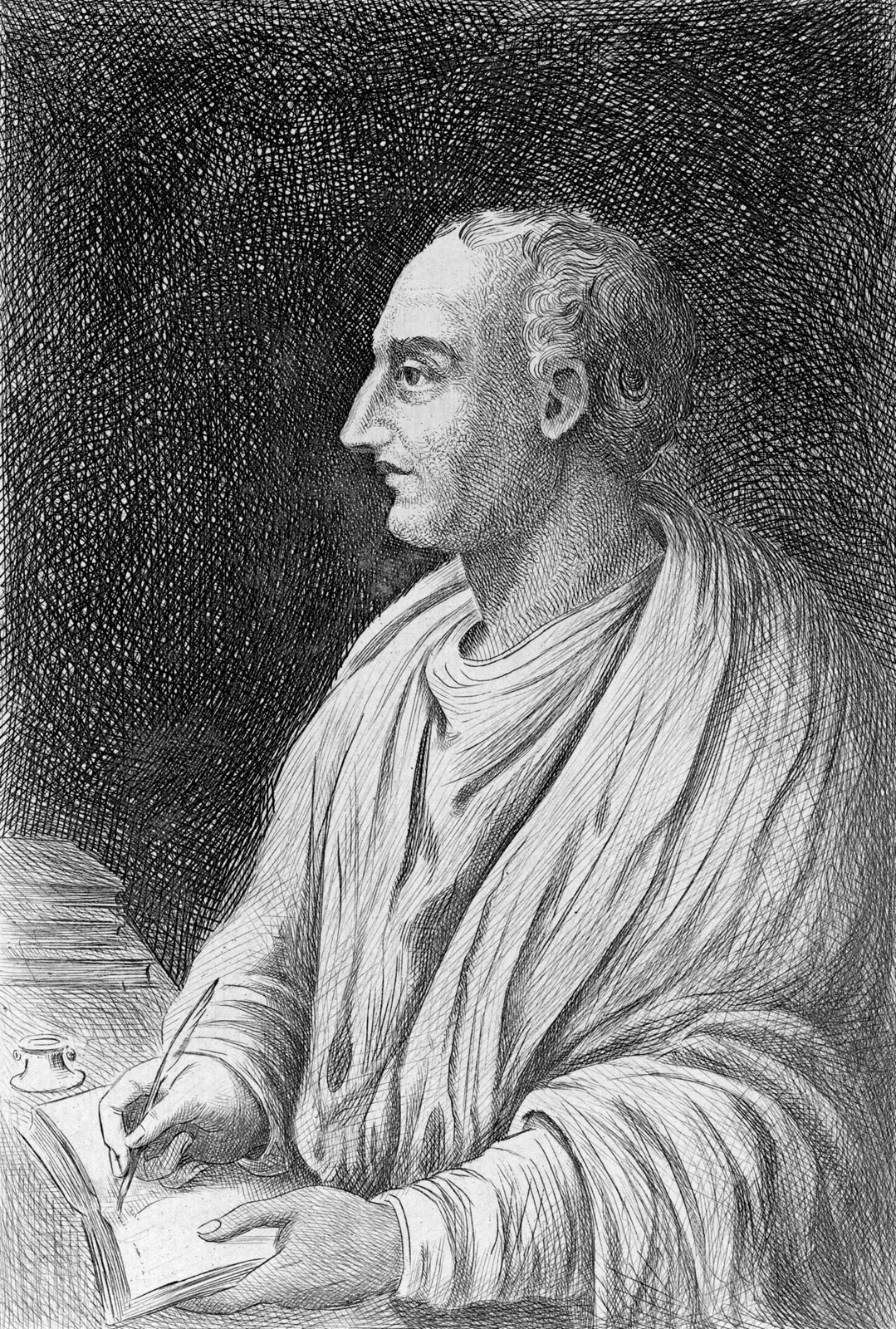

Publius Vergilius Maro, known simply as Virgil (or Vergil), stands as one of the greatest poets of ancient Rome. Born on October 15, 70 BCE, near Mantua in northern Italy, Virgil’s works have left an indelible mark on Western literature. His epic poem, The Aeneid, not only shaped Roman identity but also influenced countless writers, artists, and thinkers over the centuries. From Dante to Milton, Virgil’s voice echoes through time, embodying the ideals of Rome and the human experience.

Virgil’s life coincided with a transformative period in Roman history—the collapse of the Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire under Augustus. His works reflect the tensions between tradition and change, between the rural past and the urban future. To understand Virgil is to grasp the soul of Rome itself.

Early Life and Influences

Virgil was born into a modest rural family in the village of Andes, near Mantua. His upbringing in the Italian countryside deeply influenced his pastoral sensibilities, later showcased in his early works. Though little is known about his parents, it is believed they were small landowners, giving Virgil exposure to the rhythms of agricultural life that permeate his poetry.

Educated in Cremona, Milan, and finally Rome, Virgil studied rhetoric, philosophy, and Greek literature. Among his influences were the Hellenistic poets, particularly Theocritus, whose pastoral idylls inspired Virgil’s own Eclogues. Another significant mentor was the Epicurean philosopher Siro, whose teachings on peace and tranquility left a lasting impression on the young poet.

The Eclogues: Pastoral Dreams and Political Shadows

Virgil’s first major work, the Eclogues (or Bucolics), consists of ten pastoral poems written between 42 and 37 BCE. These poems idealize rural life, depicting shepherds engaged in poetic contests, serene landscapes, and mythological allusions. However, beneath their idyllic surface, the Eclogues reflect the political turmoil of Virgil’s time.

A particularly poignant example is Eclogue 1, which contrasts the lives of two shepherds: Tityrus, who enjoys peace thanks to divine intervention (often interpreted as Augustus’s protection), and Meliboeus, who is forced into exile due to land confiscations. The poem subtly addresses the real-world consequences of Rome’s civil wars, where veteran soldiers were given land seized from local farmers.

The Georgics: A Celebration of Labor and Nature

Following the success of the Eclogues, Virgil composed the Georgics (29 BCE), a didactic poem in four books dedicated to agriculture, viticulture, animal husbandry, and beekeeping. Commissioned by Maecenas, a close advisor to Augustus, the work was not purely practical—it was a poetic meditation on human labor and nature’s cycles.

Virgil transforms mundane farming techniques into profound reflections on life, death, and the struggle for order amidst chaos. The Georgics echoes themes of loss and renewal, particularly in its portrayal of the devastating effects of plague on livestock. The final section, focused on bees and their quasi-mythical resurrection, suggests hope amidst despair—an allegory for Rome’s resilience after years of civil war.

The Aeneid: Rome’s National Epic

Virgil’s magnum opus, The Aeneid, was commissioned by Augustus to provide Rome with a literary foundation myth rivaling Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. Composed between 29 and 19 BCE, the epic follows Aeneas, a Trojan hero who flees the burning ruins of Troy and embarks on a perilous journey to Italy, where he becomes the ancestor of the Roman people.

The poem’s first half mirrors the Odyssey, chronicling Aeneas’s wanderings and trials, including his tragic love affair with Dido, Queen of Carthage. The second half, resembling the Iliad, depicts brutal warfare between the Trojans and the native Latins. Yet, unlike Homer’s heroes, Aeneas is driven by duty (pietas)—his divine mission to found Rome outweighs personal desires.

Virgil’s Death and Unfinished Masterpiece

Virgil spent over a decade crafting The Aeneid, considering it incomplete by the time of his death in 19 BCE. According to legend, he requested the manuscript be burned, but Augustus intervened, ordering its preservation. The epic was published posthumously, instantly becoming a cornerstone of Roman literature.

Virgil’s final days were marked by illness, possibly contracted during travels to Greece. He was buried in Naples, where his tomb became a site of reverence. Later writers, including Dante, would immortalize him as a guide through the afterlife, cementing his status as the poet of human destiny.

Conclusion of Part One: The Poet’s Enduring Influence

Virgil’s works shaped not only Roman literature but also the cultural identity of the Western world. His exploration of themes—fate, duty, love, and sacrifice—resonates across centuries. In the next part of this article, we will delve deeper into The Aeneid's political significance, Virgil’s relationship with Augustus, and his lasting impact on medieval and Renaissance literature.

The Aeneid as Political Propaganda: Virgil and Augustus

Though The Aeneid is a literary masterpiece, it also served as a powerful tool of political propaganda. Commissioned by Augustus, Rome’s first emperor, the epic was designed to legitimize his rule by linking it to Rome’s mythical origins. Aeneas, the Trojan hero, embodies the virtues Augustus sought to promote—pietas (duty), gravitas (dignity), and iustitia (justice)—while his divine lineage (as the son of Venus) reinforced the Julian family’s claims to divine favor.

Throughout the poem, Virgil subtly reinforces Augustus’s authority. In Book VI, Aeneas journeys to the Underworld, where his father, Anchises, reveals a prophecy of Rome’s future greatness, culminating in the reign of Augustus. This passage not only legitimizes the emperor’s power but also presents him as the destined restorer of peace after decades of civil war. Similarly, the shield of Aeneas in Book VIII depicts key moments in Roman history, including Augustus’s victory at the Battle of Actium, blending myth and reality to craft a narrative of inevitable imperial triumph.

Ambiguities in Virgil’s Message

Despite its overtly pro-Augustan elements, The Aeneid contains undercurrents of doubt and tragedy. Aeneas’s relentless pursuit of duty comes at a personal cost—his abandonment of Dido leads to her suicide, and his victory in Italy is achieved through brutal warfare. Some scholars argue that Virgil’s portrayal of suffering undermines the poem’s celebratory tone, suggesting a more complex, even critical, perspective on imperial power.

The ending of The Aeneid is particularly contentious. Instead of a triumphant conclusion, the epic closes with Aeneas killing Turnus in a fit of rage—an act that has been interpreted as both a necessary assertion of Roman dominance and a troubling moment of unchecked fury. This ambiguity invites readers to question whether Rome’s destiny justifies its violence, leaving Virgil’s own stance open to debate.

Virgil and the Cultural Landscape of Augustan Rome

Virgil was not an isolated literary figure but a central player in the cultural revival under Augustus. The emperor’s reign saw a concerted effort to promote Roman arts as a means of unifying the state and glorifying its leadership. Alongside contemporaries like Horace and Ovid, Virgil contributed to a golden age of Latin literature that celebrated Roman values while engaging with Greek traditions.

Maecenas, Virgil’s patron, played a crucial role in this movement. As Augustus’s chief cultural advisor, he supported poets who could articulate the regime’s ideals. The Georgics, with its themes of cultivation and order, mirrored Augustus’s agricultural reforms, while The Aeneid provided a mythic framework for the empire. This collaboration between poet and state was not mere coercion—Virgil’s works suggest a genuine belief in Rome’s potential, even as they hint at its costs.

The Role of Religion and Divinity

Divine intervention pervades Virgil’s works, reflecting the Roman worldview in which gods actively shaped human affairs. In The Aeneid, Jupiter’s prophecies and Venus’s interventions underscore the inevitability of Rome’s rise, while Juno’s relentless opposition introduces tension and conflict. These divine forces align with Augustus’s religious reforms, which sought to restore traditional piety and associate the emperor with sacred authority.

However, Virgil also explores the fragility of human agency. Aeneas often struggles between divine will and personal emotion, embodying the tension between fate and free will. This nuanced portrayal of divinity suggests that Virgil’s Rome, though blessed by the gods, was not immune to moral and existential dilemmas.

The Afterlife of Virgil in Ancient Rome

Virgil’s influence was immediate and profound. By the time of his death, he was already revered as Rome’s greatest poet. Schools adopted his works as essential texts, and public readings of The Aeneid became cultural events. The emperor himself reportedly quoted Virgil’s lines at key moments, reinforcing the connection between poetry and power.

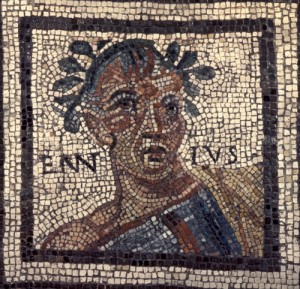

Yet Virgil’s legacy was not without controversy. Some critics, like the poet Propertius, acknowledged his genius while subtly mocking the monumental task of composing a Roman epic. Others questioned whether his portrayal of Aeneas was too idealized, lacking the flawed humanity of Homer’s heroes. Still, Virgil’s status as a literary icon remained unchallenged, and his works became foundational to Roman education.

The Legend of Virgil the Magician

In late antiquity and the Middle Ages, Virgil’s reputation took on a mythic dimension. Legends emerged portraying him as a magician or seer, capable of miraculous feats. The Sortes Vergilianae (“Virgilian Lots”) became a popular divination practice, where individuals would open The Aeneid at random and interpret its verses as prophecies. This quasi-mystical reverence blurred the line between poet and prophet, demonstrating how Virgil transcended his historical role to become a figure of legend.

Transmission and Preservation of Virgil’s Works

Virgil’s texts survived the collapse of the Western Roman Empire thanks to the efforts of medieval scribes and scholars. Monastic scriptoria meticulously copied his manuscripts, while commentators like Servius provided extensive analyses that shaped interpretations for centuries. The Carolingian Renaissance saw renewed interest in classical authors, with Virgil at the forefront, and by the High Middle Ages, his works were integral to European literary culture.

Notably, Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy (14th century) cemented Virgil’s role as the archetypal guide. In the poem, Virgil leads Dante through Hell and Purgatory, symbolizing the power of human reason—though, as a pagan, he cannot enter Paradise. This portrayal reflects the medieval view of Virgil as both a literary giant and a morally ambiguous figure, revered but not redeemed.

Conclusion of Part Two: A Bridge to Modernity

Virgil’s works bridged antiquity and modernity, influencing countless generations of writers, thinkers, and rulers. His blend of myth, politics, and philosophy ensured that his poetry remained relevant long after Rome’s fall. In the final part of this article, we will explore Virgil’s reception in the Renaissance, his impact on later literature, and his enduring presence in contemporary culture—from opera to political discourse.

Error: Response not valid

Comments