The Evolution of Film Stock: A Journey Through Cinematic History

Introduction: The Birth of Film Stock

The history of film stock is a fascinating tale of innovation, creativity, and technological advancement. From its humble beginnings in the late 19th century to its near-obsolescence in the digital age, film stock has played a crucial role in shaping the art of cinema. Before digital sensors and high-resolution video, filmmakers relied on celluloid—a flexible, light-sensitive material that captured moving images through chemical reactions. This article explores the origins, development, and cultural impact of film stock, tracing its journey from laboratory experiments to Hollywood’s golden era and beyond.

The Early Days: Celluloid and the First Motion Pictures

The story of film stock begins in the 1880s with the invention of celluloid by John Wesley Hyatt. Originally designed as a substitute for ivory in billiard balls, celluloid’s transparent and flexible properties made it an ideal medium for capturing motion. By the 1890s, George Eastman’s Kodak company began producing celluloid film rolls, enabling pioneers like Thomas Edison and the Lumière brothers to create the first motion pictures.

Early film stock was highly flammable, prone to degradation, and limited in sensitivity to light. The nitrate-based film used in silent movies was notorious for its instability—many early films were lost to decomposition or accidental fires. Despite these challenges, filmmakers embraced the medium, experimenting with storytelling techniques that laid the foundation for modern cinema.

The Rise of Safety Film and Standardization

In the 1920s, the film industry faced a crisis as nitrate film’s dangers became undeniable. Fires caused by highly combustible reels led to tragic accidents, including the 1926 destruction of a significant portion of actor Rudolph Valentino’s filmography. The solution came in the form of safety film—cellulose acetate-based stock that was far less flammable and more stable over time.

With the introduction of sound in the late 1920s, film stock needed further refinement. The optical soundtracks required precise synchronization and finer grain structure, prompting manufacturers like Kodak and Agfa to improve emulsion quality. By the 1930s, standardized film formats and improved stock allowed for richer contrast, sharper images, and more reliable color reproduction—essential for the golden age of Hollywood.

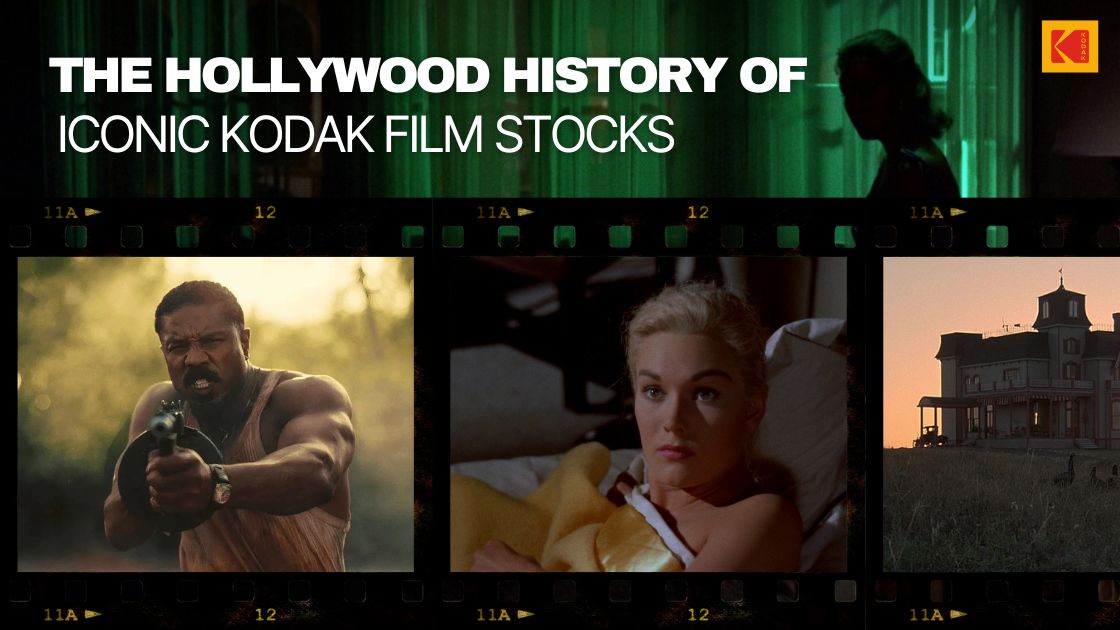

Technicolor and the Color Revolution

While black-and-white cinematography dominated early cinema, experiments with color film began as early as the 1900s. The most famous breakthrough came with Technicolor’s three-strip process in the 1930s, which used multiple layers of emulsion to capture vibrant hues. Classics like The Wizard of Oz (1939) and Gone with the Wind (1939) showcased the breathtaking possibilities of color on celluloid.

However, Technicolor was expensive and labor-intensive, leading to the development of single-strip color films in the 1950s. Eastmancolor, introduced by Kodak, democratized color cinematography, making it accessible to more filmmakers. This shift coincided with Hollywood’s battle against television, as studios used color and widescreen formats to lure audiences back to theaters.

Grain, Speed, and the Art of Cinematography

Film stock is classified by its sensitivity to light, known as "speed." Early films had low ISO (light sensitivity), requiring extensive lighting setups. The development of faster films in the mid-20th century revolutionized cinematography, allowing for naturalistic lighting in films like The French Connection (1971) and Taxi Driver (1976).

The texture of film grain also became an artistic choice—grittier films like those of the French New Wave embraced visible grain for realism, while Hollywood epics prioritized fine-grain stock for clarity. Directors and cinematographers began selecting film stocks based on aesthetic preferences, further deepening the connection between technology and artistry.

Conclusion of Part One

The first century of film stock was marked by rapid innovation, from flammable nitrate strips to the vibrant Technicolor era. As technology evolved, so did the language of cinema, with filmmakers using different stocks to evoke mood, texture, and atmosphere. In the next part, we will explore the decline of film in the digital age, the nostalgic resurgence of celluloid, and its enduring legacy in modern filmmaking.

The Decline and Nostalgic Resurgence of Film Stock

The late 20th century saw the rise of digital technology, threatening the existence of traditional film stock. With the advent of digital cameras, editing software, and computer-generated imagery (CGI), filmmakers began questioning the necessity of celluloid. Studios and cinematographers were lured by the convenience of digital workflows—no more expensive film processing, no cumbersome reels, and instant playback. By the early 2000s, major studios started adopting digital cinematography, and in 2011, Kodak, the iconic film manufacturer, filed for bankruptcy, signaling the near-end of an era.

The Digital Takeover: A Revolution in Filmmaking

The transition to digital was swift and decisive. Directors like George Lucas and James Cameron championed digital filmmaking, using high-definition cameras for films like Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones (2002) and Avatar (2009). Digital projection replaced 35mm prints in theaters, and by 2013, major Hollywood studios ceased distributing films on celluloid altogether. The cost advantages were undeniable—digital files eliminated the need for physical prints, reducing distribution expenses and piracy risks.

However, digital wasn't without its critics. Purists argued that the organic texture of film, with its subtle grain and deep color richness, couldn't be replicated by pixels. Cinematographers like Roger Deakins (Blade Runner 2049) and Christopher Nolan (Dunkirk) publicly advocated for the preservation of film, insisting that it offered a unique aesthetic that enhanced storytelling. Debates raged in the industry—was digital merely a more efficient tool, or was it eroding the art form?

The Unexpected Comeback: Why Film Never Really Died

Despite digital dominance, film stock experienced an unexpected resurgence in the 2010s. Filmmakers and studios began realizing that celluloid wasn't just a technical relic—it was a creative choice. The nostalgic warmth of film stock became a selling point for prestige projects. Quentin Tarantino, a vocal celluloid advocate, shot The Hateful Eight (2015) on 70mm Ultra Panavision, while J.J. Abrams used IMAX film for Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015). Even younger directors, like Damien Chazelle (La La Land), opted for film to evoke a classic cinematic atmosphere.

Kodak, once on the brink of collapse, was revived in part due to Hollywood’s renewed interest. Major studios struck deals to ensure a steady supply of film stock, recognizing its irreplaceable qualities. Film schools continued to teach celluloid cinematography, ensuring that new generations of filmmakers understood its historical and artistic significance. The "film vs. digital" debate evolved—instead of a binary choice, it became a question of intention and aesthetic goals.

The Science Behind the Magic: How Film Stock Works

To appreciate film’s enduring appeal, it helps to understand how it captures light. Traditional film stock consists of a plastic base coated with layers of silver halide crystals suspended in gelatin. When exposed to light, these crystals undergo a chemical reaction, forming a latent image. During development, the exposed crystals convert into metallic silver, creating the negative. Color film has additional dye layers sensitive to red, green, and blue light, which are combined to produce a full-color image.

This chemical process gives film its organic, almost painterly quality. Unlike digital sensors, which capture rigid pixel grids, film’s grain structure is irregular, creating a texture that many find more lifelike. Dynamic range—the ability to retain detail in shadows and highlights—also differs between film and digital. Some argue that celluloid handles bright skies and dark interiors more naturally, though modern digital cameras are rapidly closing the gap.

Modern Hybrid Workflows: The Best of Both Worlds?

Rather than an all-or-nothing approach, many contemporary filmmakers blend analog and digital techniques. Directors shoot on film, then scan the negatives into digital intermediates for editing and visual effects. This hybrid workflow combines film’s rich aesthetic with digital’s precision and flexibility. Movies like Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019) and Tenet (2020) used this method, preserving the texture of celluloid while enjoying the conveniences of digital post-production.

Even outside Hollywood, independent filmmakers and artists are rediscovering film. Photographers continue to embrace analog for its tactile experience, while experimental filmmakers explore hand-painted and chemically altered celluloid. The "Lo-Fi" aesthetic, characterized by imperfect grain and light leaks, has gained a cult following in music videos and commercials, proving that film’s imperfections can be its greatest strength.

Conclusion of Part Two

Film stock may no longer be the industry standard, but it has secured its place as a powerful artistic medium. Its resurgence defied predictions, proving that nostalgia alone isn’t driving its revival—it’s the irreplaceable visual and emotional impact of celluloid. In the final part of this series, we’ll explore how film is preserved today, its role in restoration projects, and what the future holds for this storied medium.

Preserving the Past, Shaping the Future: Film Stock in the Modern Era

Film Restoration: Saving Cinema’s Legacy

As digital technology evolves, film archivists face a race against time to preserve deteriorating celluloid before it’s lost forever. Nitrate film, used before 1950, is highly flammable and chemically unstable—experts estimate over 75% of silent-era films have already decomposed. Institutions like the Library of Congress and the George Eastman Museum dedicate massive resources to scanning and restoring surviving prints using wet-gate scanners that minimize scratches. Landmark restorations, from Metropolis (1927) to Apocalypse Now (1979), demonstrate how photochemical techniques paired with digital tools can resurrect films for new generations.

The Challenges of Film Preservation

Beyond decay, archivists combat “vinegar syndrome”—a chemical breakdown in acetate film that emits a pungent odor while warping the image. Unlike digital files, which degrade uniformly through bit rot, film damage is unpredictable. Color fading, mold, and improper storage conditions compound the problem. The 2008 Universal Studios vault fire—which destroyed over 100,000 audio masters and film reels—underscored the fragility of physical media, prompting studios to implement decentralized archiving strategies combining film and digital backups.

Film Stock’s Role in Education and Craft

Despite digital dominance, prestigious film schools maintain celluloid programs as core curriculum. USC and NYU require students to shoot on 16mm film to understand light sensitivity, manual focus, and the discipline of limited takes. “Film demands intentionality,” says cinematographer Rachel Morrison (Black Panther), who learned on ARRI 35mm cameras. Workshops like the Maine Media Workshops’ “Film in the Digital Age” teach techniques like bleach bypass processing and hand-cranked Bolex filming. Even in animation, studios like Laika (Kubo and the Two Strings) blend stop-motion with 3D-printed film grain for texture.

The Economics of Film in the 21st Century

While blockbusters increasingly shoot digitally, film retains niche markets. Spike Lee’s Da 5 Bloods (2020) used 16mm for wartime flashbacks, while Barbie (2023) mixed 35mm and digital for hyper-saturated dreamscapes. Paradoxically, the scarcity of film stock has increased its prestige—directors like Nolan negotiate film processing clauses into studio contracts. Kodak now positions film as a luxury product, with 35mm color negative film costing 300% more than in 2000. Small-scale manufacturers like Film Ferrania cater to indie filmmakers, while boutique labs such as Cinelab and FotoKem keep photochemical processing alive.

The Vinyl Factor: Film’s Analog Renaissance

Just as vinyl records saw a resurgence among audiophiles, film photography has exploded in popularity. Fujifilm reported a 200% increase in Instax instant film sales from 2019-2023, while Kodak Alaris doubled production of consumer film stocks like Ektachrome. Social media hashtags (FilmIsNotDead, ShootFilm) showcase a new generation discovering analog’s tactile joys. Directors like Barry Jenkins (Moonlight) credit this revival with keeping film manufacturing viable: “Instagram photographers shooting $10 Kodak Gold are subsidizing Hollywood’s film supply.”

Technological Hybridization: The Next Frontier

Emerging technologies bridge the analog-digital divide. ARRI’s Texture Library scans real film grain to digitally overlay onto Alexa footage. Dehancer and FilmConvert plugins emulate specific stocks like Kodak Vision3 250D. Even AI enters the conversation—Google’s “Analog Diffusion” generates synthetic film grain patterns. Meanwhile, researchers at MIT are developing “Quantum Film,” nano-engineered sensors that mimic silver halide crystals for ultra-high-resolution imagery with organic textures.

The Eternal Debate: Authenticity vs. Replication

Purists argue digital emulation can’t replicate film’s serendipitous flaws—the slight fogging in overexposed highlights, grain clustering in shadows. Tests by the American Society of Cinematographers show that while ARRI’s digital grain comes close to 35mm, it lacks the microscopic randomness of chemical development. For restoration specialists like Grover Crisp at Sony Pictures, “Digital shines at repairing damage, but only photochemical prints preserve the original artistic intent.”

What Lies Ahead for Film Stock?

As streamlines push toward 8K resolution, some predict film’s ultimate demise given its theoretical resolution limit around 6K scans. Yet others counter that resolution isn’t everything—Oscar-winning cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema (Oppenheimer) insists IMAX 70mm film delivers resolution exceeding 12K through its organic grain structure. Looking forward, three paths emerge: film as a specialty format for auteurs, as a niche boutique product, or as a conceptual influence guiding digital aesthetics regardless of physical use.

Final Frame: A Lasting Imprint on Visual Culture

Film stock’s journey from revolutionary invention to endangered species to cultural artifact reflects cinema’s broader evolution. Whether used practically or philosophically, celluloid remains foundational to visual storytelling—its grain structure subconsciously cues audiences to interpret images as “cinematic.” From Tarantino’s nostalgic 35mm to Chloé Zhao’s digitally graded “film look” in Nomadland, the language of celluloid persists even as the medium transforms. Perhaps film’s ultimate legacy isn’t just preserved in vaults, but in how it shaped our collective visual imagination forever.

Epilogue: The Never-Ending Reel

As flickering projector lights give way to streaming pixels, one truth endures: film stock is more than emulsion on plastic—it’s the DNA of cinema itself. The next century will see film stocks archived, emulated, innovated, and perhaps even reinvented, but their impact on how we see the world remains immortal.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/film-photography-592347645-59e4d0609abed500119e7b14.jpg)

.webp)

Comments