Ptolemy IV Philopator: The Man and His Dynasty

Ptolemy IV Philopator, known as Philopator, was a pharaoh of the Ptolemaic Kingdom who reigned from 221 BC until his death in 204/203 BC. Born to Ptolemy III Euergetes and his wife Berenice II, Philopator came to power at a young age amid a period of political upheaval that would define much of his reign.

Early Life and Accession

Born around 240 BC, Ptolemy Philopator was the eldest son of Ptolemy III and his primary wife Berenice II. From a young age, he was groomed for the throne amidst the complex political landscape of the Hellenistic world. His lineage traced back to Ptolemy I Soter, a general of Alexander the Great who founded the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Egypt after Alexander's death.

The reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus, his grandfather, had been marked by both prosperity and tension. Upon Ptolemy II’s death in 246 BC, Ptolemy III ascended the throne, bringing about a more assertive foreign policy aimed at territorial expansion and securing the kingdom’s wealth. Despite the successes under his father, the reign of Ptolemy III was also marred by internal strife, particularly the conflict with his younger brother and co-ruler Philip. When Philip was murdered in 222 BC, leaving only Ptolemy IV and his younger siblings to inherit the throne, the young Philopator became pharaoh at the age of about thirteen.

Administration and Foreign Policy

Upon his accession, Philopator faced a multifaceted set of challenges. These included maintaining stability within Egypt, managing the intricate diplomacy required to navigate the Hellenistic world, and ensuring the financial health of the state.

The administrative structures of the time were elaborate and extensive. Philopator inherited a bureaucracy that oversaw the vast lands of the Ptolemaic Empire, including control over the Nile valley, coastal regions, and various colonies established by earlier Ptolemies. Central to this system was the role of the satrapes, local governors responsible for administration and taxation. However, reports from the period suggest that these officials often abused their power, leading to unrest among the populace and neighboring kingdoms.

Philopator’s administration sought to address these issues through a combination of direct intervention and diplomatic efforts. For example, in the early years of his reign, he focused on establishing his authority by engaging in military campaigns aimed at securing Egypt’s borders. One notable campaign was against the Seleucid Empire, particularly targeting Syria and Palestine. While these military ventures often yielded mixed results, they demonstrated the Ptolemaic commitment to maintaining a strong defense posture.

Internally, Philopator took steps to improve administration and reduce corruption. He may have implemented reforms in the tax collection process and sought to centralize certain aspects of government. Nonetheless, the effectiveness of these changes remains debatable, given the limited sources available and the recurring complaints from Greek citizens living in Ptolemaic territories.

Cultural Patronage and Challenges

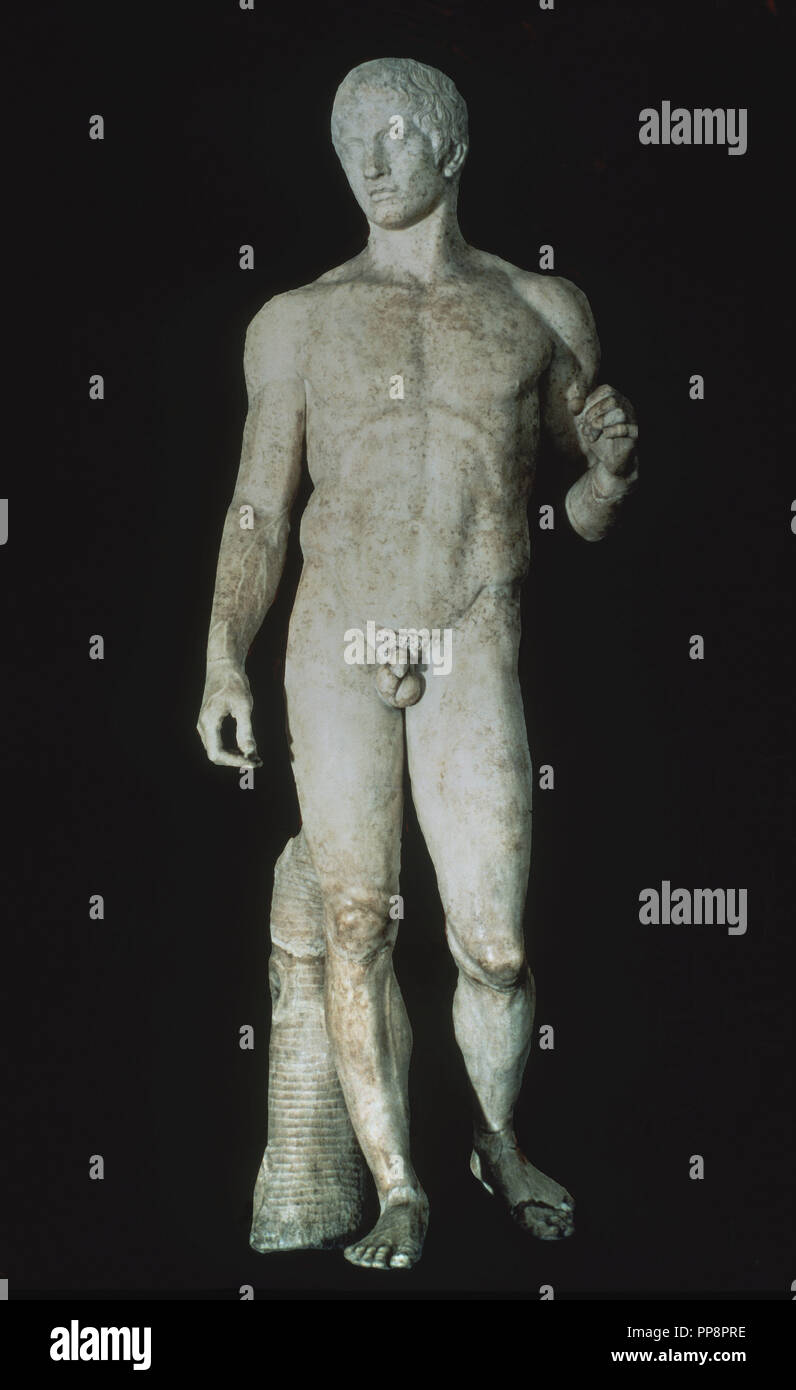

Philopator’s reign is marked by significant cultural patronage, particularly in the fields of art, politics, and literature. He continued the tradition of supporting Greek culture and art, which had been fostered by his predecessors. The royal court attracted numerous artists, poets, and scholars, making Alexandria a vibrant center of learning and creativity.

A notable example of this cultural engagement is the construction and ornamentation of the temples, especially the famous temple of Philae dedicated to Isis. The presence of such artistic endeavors not only reflected the wealth and grandeur of the Ptolemaic dynasty but also served a political function, demonstrating their divine favor and connection to Egyptian traditions.

Despite these outward displays of cultural prosperity, Philopator’s reign faced significant challenges. One major issue was the increasing dissatisfaction among the Greek population over the economic policies of the Ptolemaic rule. The imposition of heavy taxes and the perceived exploitation of Greek citizens by the royal administration sparked discontent, leading to periodic unrest and rebellion.

An additional challenge was the growing power of the priestly class, particularly those associated with temples like Philae. These religious authorities increasingly held influential positions and wielded considerable influence over the governance of both the state and society. Their power base often competed with that of the pharaoh and his administration, creating tensions that could be exploited by political adversaries.

A significant turning point in Philopator’s reign came in the form of political intrigue and the rise of his younger brother Arsinoe III. Arsinoe, who was married to the powerful general Apion, began to wield considerable political influence. This situation reached a critical juncture when Arsinoe conspired to depose Philopator, leading to a period of intense civil unrest.

The conflict with Arsinoe and her supporters ultimately culminated in a series of dramatic events that reshaped the political landscape of the Ptolemaic kingdom. Arsinoe’s attempts to seize control highlighted the underlying tensions within the dynastic succession and the broader social and political structures of the era. These events serve as a stark reminder of the delicate balance of power that existed during Ptolemaic times and the potential for upheaval even among stable ruling families.

The Political Intrigue and Conspiracies

The political intrigue surrounding Philopator reached new heights with the rise of Arsinoe III and her husband, the general Apion. Arsinoe’s ambitions were not confined to power; she sought to undermine Philopator’s rule directly. Arsinoe’s involvement in a conspiracy against Philopator was rooted in personal grievances and strategic interests. According to contemporary sources, Arsinoe resented her position as one of many wives while Philopator favored other concubines, particularly Agathoclea, a woman who would later play a significant role in the events leading up to Philopator’s downfall.

The conspiracy involved a series of well-planned actions designed to destabilize Philopator’s rule. Arsinoe orchestrated a false plot involving an alleged uprising among the troops stationed outside Alexandria. This ruse was intended to provoke Philopator into taking decisive action, thereby providing an excuse for dismissing high-ranking administrators and consolidating power for herself and Apion.

When the supposed revolt was quashed, Philopator was left in a weakened position. The episode marked a turning point in Philopator’s life, highlighting the internal strife within the palace and the manipulation of power dynamics. As tensions escalated, Philopator found himself boxed in, both politically and personally. The situation was further complicated by the influence of Agathoclea, who reportedly encouraged Philopator to move against Arsinoe and Apion.

Philopator, possibly motivated by both personal vindication and political necessity, ordered the execution of Arsinoe in 217 BC. This act marked a significant shift in his reign, as it demonstrated his willingness to make drastic decisions and signaled the end of Arsinoe’s ambitions. However, the aftermath of Arsinoe’s execution was fraught with consequences. The move ignited widespread outrage among the populace, particularly among the Greeks, who viewed the act as an arbitrary and harsh punishment. This backlash contributed to growing instability within the kingdom.

Royal Favoritism and Domestic Policy

Philopator’s reign was marked by a series of high-profile appointments and patronages, particularly favoring Agathoclea and other members of the royal household. Agathoclea’s rise to prominence can be attributed to several factors, including her close relationship with the king and her ability to maneuver within the complex political landscape. She was not only a trusted advisor but also played a crucial role in managing the royal finances and overseeing some of the key decisions made during Philopator’s reign.

One of Agathoclea’s most notable contributions was the construction of the Serapeum, a massive temple dedicated to Serapis. This project was part of a broader program of religious and cultural patronage that sought to consolidate the king’s divine image. The serapeum became a symbol of the Ptolemaic dynasty’s commitment to blending Hellenic and Egyptian religious practices, reflecting the dynasty’s attempt to legitimize its rule and strengthen its bond with the Egyptian people.

Agathoclea’s influence extended beyond religious projects. She was instrumental in shaping the royal court and its policies, often serving as a mediator between the king and his subjects. Her ability to navigate the complexities of royal politics earned her favor, but it also made her a target of criticism from other factions within the kingdom. Critics accused her of amassing wealth and power at the expense of the common good, leading to accusations of corruption and mismanagement.

Despite the growing backlash against Agathoclea and her growing importance, Philopator remained largely indifferent to public sentiment. His personal relationship with Agathoclea and his trust in her advice overshadowed any concerns about her influence. This dynamic reflected a broader trend within the Ptolemaic administration, where personal relationships and family connections often trumped broader public interests.

Military Campaigns and Diplomacy

Philopator’s reign saw continued engagement in military campaigns aimed at securing and expanding the Ptolemaic sphere of influence. One of the most significant ventures was the campaign against the Seleucid Empire, specifically the conflict for control of Coele-Syria. This region, situated along the eastern border of the Ptolemaic territories, was a strategic focal point due to its proximity to other major powers such as the Seleucids and the Armenians. Control over Coele-Syria not only secured a buffer zone but also provided access to vital resources and trade routes.

The Ptolemaic army, under the command of Ptolemy Apion, conducted several campaigns to subdue the Seleucid presence in Coele-Syria. These campaigns were initially successful, leading to the capture of several cities and the displacement of Seleucid influences in the region. However, the prolonged nature of these wars brought significant military and financial burdens to the Ptolemaic state. The demands placed on the military and the resources required for sustained warfare led to increased taxation, further exacerbating the already strained relations with the Greek populations.

In response to these challenges, Philopator attempted to manage the kingdom’s external threats through a combination of military might and diplomatic maneuvers. He recognized the need for allies, both within and beyond the empire, to counterbalance the power of the Seleucids. Diplomatic efforts included forming alliances with local rulers and negotiating agreements with neighboring states. For instance, Philopator established a positive relationship with Artaxias, the founder of the Armenian Empire, fostering a strategic alliance that helped to mitigate Seleucid pressures from the north.

Nevertheless, the military campaigns and diplomatic efforts took their toll. By the late stages of Philopator’s reign, the kingdom was burdened with the costs of ongoing warfare, including the maintenance of large armies and the procurement of supplies. Economic strain inevitably impacted the everyday lives of Egyptians and Greeks alike, leading to further discontent and unrest.

Legacy and Death

As Philopator neared the end of his reign, the political and social tensions that characterized his rule began to weigh heavily on his health and mental well-being. Reports suggest that he suffered from a chronic illness that affected his mobility, often confining him to his bedchamber. This condition made governing from the heart of the Egyptian capital, Alexandria, increasingly challenging. The king became reliant on his advisors, particularly Agathoclea, whose counsel shaped many of his decisions in the latter years of his rule.

The final years of Philopator’s reign were marked by a series of dramatic events and conspiracies. Amid his ill health and the deteriorating political climate, two significant assassins emerged—one from inside the palace and another from the streets. These assassins, driven by personal vendettas and political intrigue, managed to enter the royal chamber where Philopator lay bedridden. They struck fatal blows, ending the life of the young pharaoh, who had ascended to the throne so precociously.

The manner of Philopator’s death and the sequence of events surrounding his demise fueled rumors and theories about the circumstances of his passing. Some accounts suggested that Agathoclea had a hand in orchestrating the assassination, although others posited that the king’s illness made him vulnerable to such an attack. Regardless of the precise details, Philopator’s untimely death marked the end of an era and set the stage for a new phase in Ptolemaic history.

With Philopator’s death in either 204 BC or 203 BC, the throne passed briefly to his infant son Ptolemy V Epiphanes (r. 203–180 BC), who continued to be under the regency of Agathoclea. The Ptolemaic dynasty, which had endured for centuries, would face numerous challenges in the coming decades, but Philopator’s tumultuous reign left a lasting legacy of political intrigue and internal strife.

In summary, Philopator’s rule was characterized by a complex interplay of political intrigue, military campaigns, and personal patronage. From the early struggles against internal rivals like Arsinoe III to the external pressures of the Seleucid Empire, Philopator navigated a treacherous path marked by both success and failure. While his achievements in cultural patronage and architecture were significant, his inability to address internal and external threats effectively left an indelible mark on the Ptolemaic kingdom. The events of his reign foreshadowed the broader challenges that would face subsequent pharaohs, ultimately contributing to the decline of the dynasty.

Okay, the user wants me to write the third part of the article about Ptolemy IV Philopator, focusing on his legacy and the broader implications of his reign. I need to make sure this section is around 1200 words without repeating the H1. Let me start by reviewing the previous parts to avoid repetition. The first part covered his early life, administration, and cultural aspects. The second part dealt with political intrigue, military campaigns, and his death.

Now, for the third part, the focus should be on his legacy, how his reign influenced the Ptolemaic dynasty, and his impact on the Hellenistic world. I should discuss the immediate aftermath of his death, the regency of Ptolemy V under Agathoclea, and the broader consequences of his policies. Also, the transition period under his son and the eventual decline of the dynasty.

I need to ensure that the content flows logically, connecting the points from the previous sections. Maybe start with the aftermath of his death, the regency, and then move to the long-term effects on the kingdom. Also, mention how his reign compared to other Ptolemies and the historical significance of his contributions and failures.

I should include details about the political instability after his death, the influence of Agathoclea, the economic strains, and how these factors contributed to the decline. Also, touch on the cultural achievements and how they were maintained or affected by the events of his reign.

Need to check for any historical inaccuracies. For example, Ptolemy V's regency under Agathoclea, the role of the priestly class, and the impact of the wars on the economy. Also, ensure that the legacy part highlights both positive and negative aspects, giving a balanced view.

I should also mention the dynastic issues that plagued the Ptolemies, the succession problems, and how Philopator's reign exemplified these. Maybe link his personal controversies to the broader trend of Ptolemaic rulers being more preoccupied with court politics than governance.

Finally, conclude with the overall significance of Philopator's reign in the context of Hellenistic history, emphasizing the challenges of ruling a multi-ethnic state and the complexities of balancing Greek and Egyptian traditions.

The Aftermath of Philopator’s Death and the Rise of Ptolemy V

The death of Ptolemy IV Philopator marked the beginning of a turbulent period for the Ptolemaic dynasty, as power vacuums and unresolved tensions threatened to destabilize the kingdom. Despite his early death at around 17 or 18 years old, Philopator’s reign had already left a legacy of political uncertainty, economic strain, and internal strife. His infant son, Ptolemy V Epiphanes, was too young to rule, and the throne fell into the hands of the powerful Agathoclea, who assumed the role of regent. Her influence over the young king would define the immediate years following Philopator’s death and set the stage for further instability in the Ptolemaic state.

Agathoclea, already a controversial figure during Philopator’s reign, now found herself at the center of power. Her autocratic rule and perceived favoritism sparked protests and rebellions, particularly among the Greek population of Alexandria, who resented the increasing dominance of native Egyptian elites and the autocratic tendencies of the Ptolemaic court. The tension between Greek and Egyptian populations, a long-standing issue in the kingdom, reached a boiling point under her regency. This unrest was compounded by the economic hardships inherited from Philopator’s reign, including the burdens of war, heavy taxation, and the depletion of state resources.

One of the most significant consequences of Philopator’s short reign was the weakening of the Ptolemaic monarchy’s influence over its vast territories. The military campaigns in Coele-Syria had drained the kingdom’s finances and military strength, leaving the Ptolemaic administration vulnerable to external threats. The Seleucid Empire, which had long competed with Egypt for control of the Levant, seized the opportunity to assert dominance in the region. In 201 BC, the Seleucid king Antiochus III launched a full-scale invasion of Egypt, aiming to expel the Ptolemies from Syria and reclaim lost territories. This campaign, known as the Syrian War, would become one of the most defining conflicts of the Ptolemaic era and revealed the fragility of Philopator’s legacy.

The Syrian War exposed the Ptolemaic military’s inability to resist the Seleucids in the absence of a strong, experienced king. Ptolemy V, still a child, was unable to direct a coherent defense, and the Ptolemaic forces, already weakened by years of war and financial strain, were no match for Antiochus III’s disciplined and better-equipped army. The Seleucids advanced deep into Egyptian territories, capturing key cities and threatening to seize Alexandria itself. This crisis underscored the Ptolemaic dynasty’s dependence on external alliances and the growing instability of its internal political structure.

The Decline of Ptolemaic Power and the Role of the Priestly Class

The crisis fueled by Antiochus III’s invasion was not merely a military failure but also a sign of the broader decline of Ptolemaic rule. The dynasty’s reliance on centralized control, patronage of the royal court, and the fusion of Greek and Egyptian traditions had, over the decades, generated a deep divide between the ruling elite and the general populace. The priestly class, particularly the high priests of state temples, had grown increasingly powerful, often challenging the authority of the pharaoh and manipulating religious institutions to serve their own interests.

During Philopator’s reign, the growing influence of the priesthood had already begun to erode the Ptolemaic monarchy’s authority. By the time of Ptolemy V’s regency, this trend had escalated, with priests and temple officials functioning as de facto rulers in many regions of the kingdom. The construction of grand temples, such as the Serapeum, had solidified their status, and their control over religious festivals and rituals gave them immense social and political capital. This power was further amplified by the Ptolemaic practice of syncretism, which blended Greek and Egyptian religious practices. While this policy had initially served to legitimize Ptolemaic rule, it also enabled the priesthood to claim divine authority independent of the monarchy, creating a dangerous power dynamic.

The priestly class’s influence was particularly evident in the political maneuvering that followed Philopator’s death. Some priests, seeing an opportunity to weaken the regency of Agathoclea, supported rebellions against the central government. These insurrections, combined with the external threat posed by Antiochus III, placed Ptolemy V’s regency in a precarious position. The young king’s inability to assert his authority further emboldened the priesthood and other political factions, leading to a period of civil unrest that would persist for years.

Antiochus III’s invasion came to a critical turning point in 196 BC, when the Battle of Panium marked the Seleucids’ decisive victory over the Ptolemaic forces in Palestine. This defeat symbolized the end of Ptolemaic dominance in the Levant and forced the regent Agathoclea to negotiate with Antiochus III. In a desperate bid to preserve the kingdom, she signed the Treaty of Apamea, which ceded much of the Levant to the Seleucids and imposed heavy reparations on Egypt. The terms of this treaty not only weakened the Ptolemaic economy further but also undermined the moral authority of the monarchy, as it was seen as a humiliating concession to a foreign power.

Cultural and Intellectual Contributions Amidst Turmoil

Despite the political and military challenges, the Ptolemaic period under Philopator and his successors remained a golden age of cultural and intellectual achievement. The Library of Alexandria, founded during the reign of Ptolemy I Soter, had grown into one of the most significant centers of knowledge in the ancient world. Philopator’s reign, though marked by instability, saw continued investment in this institution, as well as the patronage of scholars, artists, and philosophers who sought to bridge Greek and Egyptian traditions.

The Ptolemaic rulers, including Philopator, were patrons of the arts and sciences, maintaining the tradition of commissioning grand architectural projects and supporting the study of mathematics, astronomy, and medicine. The Serapeum of Alexandria, dedicated to the god Serapis, was not only a religious site but also a hub for intellectual exchange, attracting scholars from across the Hellenistic world. While the political instability of the era may have disrupted some of these endeavors, the legacy of Ptolemaic cultural patronage endured well beyond Philopator’s reign.

Philopator’s own contributions to this cultural legacy were evident in his support for religious institutions and the construction of monuments. The grand temples dedicated to Serapis and Isis, including the Serapeum in Alexandria and the sanctuary at Philae, were emblematic of the Ptolemaic kings’ efforts to project stability, divine favor, and cultural synthesis. These structures not only served religious purposes but also reinforced the legitimacy of the Ptolemaic dynasty, which sought to present itself as both Greek and Egyptian in origin.

Philopator’s Legacy in the Context of the Ptolemaic Dynasty

In evaluating Philopator’s reign, it is essential to consider the broader context of the Ptolemaic dynasty’s struggles. The Ptolemies, descendants of Alexander the Great’s general Ptolemy I Soter, had inherited a vast and diverse empire that spanned from Egypt to the eastern Mediterranean. However, their rule was never entirely uncontested, as they faced persistent challenges from within their own court, the Greek population of Alexandria, and external powers such as the Seleucids, the Roman Republic, and the rising Carthaginian Empire.

Philopator’s reign, though marked by personal and political controversies, was emblematic of the Ptolemaic kings’ delicate balancing act between Greek and Egyptian traditions. His attempts to assert centralized authority, coupled with his patronage of Greek culture and architecture, reflected the dynasty’s efforts to maintain legitimacy in a multi-ethnic state. However, these strategies often exacerbated tensions rather than resolved them, contributing to the eventual decline of the Ptolemaic kingdom.

The legacy of Philopator’s reign also lies in the patterns of succession and regency that characterized the Ptolemaic dynasty. The assassination of Philopator under mysterious circumstances, the regency of Agathoclea, and the fragile rule of Ptolemy V set a precedent for the Ptolemaic succession crises that would follow. Subsequent pharaohs, including Ptolemy VI Philometor and Ptolemy VII Neos Philopator, would face similar challenges, with power struggles, external invasions, and internal instability becoming the norm rather than the exception.

Furthermore, Philopator’s reign serves as a microcosm of the broader Hellenistic world’s political and social dynamics. The Ptolemaic dynasty, like its counterparts in the Seleucid and Antigonid kingdoms, grappled with the complexities of ruling a multicultural empire while maintaining the illusion of centralized power. The tensions between native Egyptian populations and Greek settlers, the influence of the priesthood, and the interplay of religion and politics all played crucial roles in shaping the trajectory of the Ptolemaic state.

Conclusion: The End of an Era and the Memory of Philopator

Ultimately, Ptolemy IV Philopator’s reign, though brief and fraught with challenges, remains significant in the history of the Ptolemaic dynasty and the broader Hellenistic world. His early death marked the end of the dynasty’s first great period of stability, ushering in an era of decline and fragmentation that would culminate in the eventual Roman conquest of Egypt. Yet, his contributions to the cultural and architectural legacy of the Ptolemaic state endured, ensuring that even in the face of political turmoil, the Hellenistic world would remember the achievements and controversies of his reign.

The memory of Philopator, like that of his successors, was shaped by the historical narratives that followed. Later Ptolemaic rulers, including the enigmatic Cleopatra VII, would grapple with the same struggles of maintaining legitimacy, navigating succession crises, and resisting external pressures. While Philopator’s reign may not have offered long-term solutions to these challenges, it undeniably set the stage for the complex and often tragic history that would define the Ptolemaic Dynasty until its end.

In the end, Philopator’s story is not one of triumph but of the fragility of power in the Hellenistic world. His life, marked by personal ambition, court intrigue, and the burdens of royal rule, encapsulates the paradox of the Ptolemaic kings—figures who strove to unite Greek and Egyptian traditions in the service of an empire, yet continually faced the disunity and strife that defined their reign. As the Ptolemaic Dynasty moved ever closer to its fate under Roman rule, Philopator’s legacy remained a poignant reminder of the impermanence of power and the enduring complexities of governance in a multi-ethnic, multi-religious empire.

Comments