Praxiteles: The Revolutionary Sculptor of Ancient Greece

Introduction: The Master of Marble and Human Form

Praxiteles, one of the most celebrated sculptors of ancient Greece, redefined classical art with his innovative approach to the human form. Active during the 4th century BCE, his work marked a departure from the rigid idealism of earlier Greek sculpture, introducing a softer, more naturalistic style that emphasized grace, emotion, and sensuality. Praxiteles’ mastery of marble and bronze transformed the way gods, goddesses, and mortals were depicted, leaving an indelible mark on Western art history.

This article explores the life, artistry, and enduring legacy of Praxiteles, focusing on his most famous works, the techniques that set him apart, and his influence on subsequent generations of artists.

The Life and Times of Praxiteles

Little is known about Praxiteles’ personal life, a common challenge when studying ancient artists. Historical records suggest he was born around 395 BCE, possibly in Athens, into a family of sculptors. His father, Cephisodotus the Elder, was also a renowned artist, indicating that Praxiteles may have learned his craft through a traditional apprenticeship within his family.

The 4th century BCE was a period of transition in Greek art and society. The city-states were recovering from the Peloponnesian War, and there was a growing interest in individualism and emotional expression, themes that Praxiteles would later embody in his sculptures. Unlike the heroic and austere figures of the High Classical period, Praxiteles’ work embraced a more intimate and humanized approach, making his art relatable to the people of his time.

Revolutionizing Greek Sculpture: Style and Technique

Praxiteles’ style is characterized by several key innovations that distinguished him from his predecessors:

1. Naturalism and Sensuality

While earlier Greek sculptors focused on idealized, flawless representations of the human form, Praxiteles introduced a sense of realism and vulnerability. His figures seemed to breathe and move, with delicate curves and lifelike flesh. One of his most groundbreaking contributions was his depiction of the human body in relaxed, natural poses, often with a subtle “S-curve” stance known as contrapposto.

2. The Use of Marble

Praxiteles was a master of marble, a material that allowed him to achieve unprecedented levels of detail and softness in his sculptures. While bronze was still widely used during his time, he preferred marble for its ability to capture the play of light and shadow, enhancing the lifelike quality of his figures. His skill in carving flowing drapery and delicate facial expressions set new standards for sculptural craftsmanship.

3. Emotional Expression

Breaking away from the stoic expressions of earlier Greek statues, Praxiteles infused his works with emotion. His figures often conveyed a sense of introspection, tenderness, or even melancholy, making them more relatable to viewers. This focus on inner life was revolutionary in a tradition that had previously prioritized grandeur and detachment.

Famous Works of Praxiteles

Although many of Praxiteles’ original sculptures have been lost to time, Roman copies and written accounts provide insight into his most celebrated creations. Below are some of his most influential works:

1. The Aphrodite of Knidos

Perhaps his most famous work, the *Aphrodite of Knidos*, was the first large-scale Greek sculpture to depict a fully nude goddess. This daring representation shocked and fascinated audiences, as it broke conventions by showing Aphrodite in a vulnerable, humanized state. The sculpture was renowned for its beauty and sensuality, reportedly inspiring admiration and even infatuation among viewers.

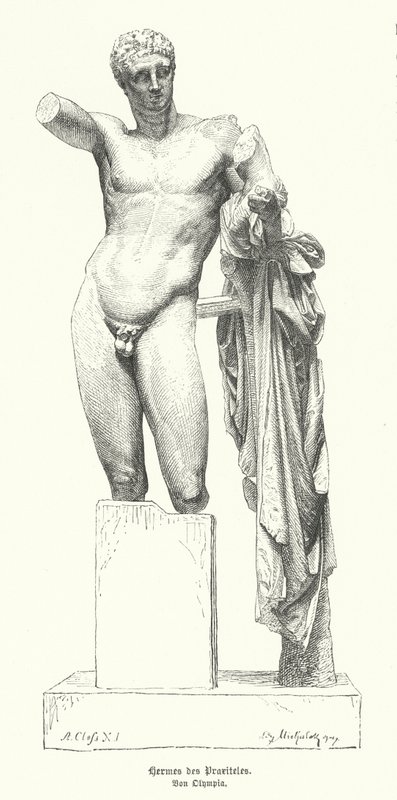

2. Hermes and the Infant Dionysus

This marble statue, discovered in the ruins of the Temple of Hera at Olympia in 1877, is one of the few surviving works possibly attributed to Praxiteles. It depicts Hermes holding the infant Dionysus in a playful, affectionate pose. The intricate detailing of Hermes’ musculature and the delicate treatment of the infant’s form exemplify Praxiteles’ mastery.

3. Apollo Sauroktonos

The *Apollo Sauroktonos* (Apollo the Lizard-Slayer) is another notable work, showcasing Praxiteles’ ability to capture movement and youthfulness. The statue depicts the god Apollo leaning against a tree, preparing to strike a lizard with an arrow. The relaxed pose and playful theme were a departure from the typical heroic depictions of gods.

Praxiteles’ Legacy and Influence

Praxiteles’ innovations did not go unnoticed. His emphasis on naturalism and emotion influenced generations of Hellenistic sculptors and later Roman artists. Even Renaissance masters such as Michelangelo studied his techniques, particularly his ability to make marble appear soft and animate.

Despite the loss of many originals, Roman copies ensured that Praxiteles’ style endured, allowing modern audiences to appreciate his contributions. His work remains a cornerstone of classical art, celebrated for its humanity, elegance, and timeless beauty.

(To be continued in Part 2, where we will delve deeper into the historical context of Praxiteles' work, controversies surrounding his sculptures, and their impact on modern art.)

The Historical Context of Praxiteles’ Work

To fully understand Praxiteles' contributions to ancient Greek art, it is essential to examine the cultural and political landscape of his time. The 4th century BCE was a period of profound transformation in Greece, marked by shifting artistic tastes and the rise of new philosophical ideas.

1. The Aftermath of the Peloponnesian War

The devastating Peloponnesian War (431–404 BCE) had left Athens weakened, both economically and politically. The loss of the conflict to Sparta created an atmosphere of introspection, influencing art to shift from overtly heroic depictions to more nuanced, personal expressions. Praxiteles' sculptures, with their emphasis on grace and subtle emotion, resonated with a society seeking solace and beauty in times of upheaval.

2. The Rise of Individualism in Art

Prior to the 4th century BCE, Greek sculpture was dominated by idealized representations meant to embody universal virtues—strength, wisdom, and divine perfection. However, the increasing influence of philosophers like Plato and Aristotle encouraged a deeper exploration of individual character and human vulnerability. Praxiteles embodied this shift by sculpting gods and mortals with relatable emotions, flaws, and sensuality, bridging the gap between the divine and the human.

3. The Evolving Role of Religion and Beauty

Religion in ancient Greece was intertwined with daily life, yet the perception of gods and goddesses was evolving. No longer distant and austere, deities were increasingly seen as approachable and even flawed—much like humans. Praxiteles' *Aphrodite of Knidos*, with its unabashed celebration of the female nude, reflected this changing relationship between worship and artistic representation. Beauty was no longer just an abstract ideal; it became something personal, tactile, and emotional.

Controversies and Scandals Surrounding Praxiteles’ Work

Despite his acclaim, Praxiteles’ sculptures were not without controversy. His bold innovations often shocked his contemporaries and sparked debates about propriety and artistic freedom.

1. The Nudity of the Aphrodite of Knidos

The *Aphrodite of Knidos* was revolutionary not just for its technical brilliance but also for its unprecedented portrayal of a goddess in the nude. Before Praxiteles, female figures were typically depicted clothed, with male nudes dominating Greek sculpture. According to ancient sources, Aphrodite’s exposed form was so lifelike and alluring that it reportedly caused scandal and public fascination in equal measure. Some accounts even claim that a young man became so obsessed with the statue that he attempted to defile it—a story that underscores its powerful impact.

2. The Enigmatic Identity of Models

Another point of intrigue is whether Praxiteles used real-life models for his divine figures. Some historians speculate that the famous courtesan Phryne, who was also his lover, posed for the *Aphrodite of Knidos*. While there is no definitive proof, the idea further emphasizes how Praxiteles blurred the lines between sacred and profane, immortal and mortal.

3. The Debate Over Roman Copies

Many of Praxiteles’ original sculptures have been lost, and most surviving examples are Roman copies. This raises questions about how faithfully these reproductions captured his original style. Some scholars argue that Roman artists may have idealized or altered aspects of his work to suit their tastes, making it difficult to assess Praxiteles’ true techniques with absolute certainty.

Praxiteles and the Hellenistic Evolution of Art

Praxiteles’ influence extended well beyond his lifetime, serving as a bridge between the Classical and Hellenistic periods of Greek art. His emphasis on realism, emotion, and dynamic poses paved the way for later sculptors to explore even more expressive and dramatic compositions.

1. The Impact on Hellenistic Masters

Artists like Lysippos and Scopas took inspiration from Praxiteles’ naturalism but pushed it further into theatricality and exaggerated movement. The famous *Laocoön and His Sons*, a masterpiece of Hellenistic sculpture, owes much to Praxiteles’ ability to convey pain and tension through the human form.

2. The Spread of His Influence Across the Mediterranean

As Greek culture spread during the Hellenistic era, so did Praxiteles’ artistic legacy. His works were admired and replicated across the Mediterranean, from Alexandria to Rome, ensuring that his style remained influential for centuries. Even in distant regions, local sculptors adapted his techniques, blending them with their own traditions.

Rediscovery and Modern Interpretations

The rediscovery of Praxiteles’ works during the Renaissance reignited interest in his artistry, with later artists drawing from his innovations to shape Western art traditions.

1. The Renaissance Revival

Italian Renaissance sculptors, including Michelangelo, closely studied surviving Roman copies of Praxiteles’ works. The *Aphrodite of Knidos* became a touchstone for portrayals of female beauty, influencing iconic pieces like Botticelli’s *The Birth of Venus*. Michelangelo’s *David*, while more muscular, still reflects Praxiteles’ mastery of the human form in marble.

2. Modern Archaeology and Scholarly Debates

Excavations in the 19th and 20th centuries uncovered several potential Praxitelean works, such as the *Hermes and the Infant Dionysus*. However, debates persist over their authenticity. Advanced techniques like 3D scanning and material analysis now allow historians to study these sculptures in unprecedented detail, offering new insights into his workshop practices.

3. Praxiteles in Contemporary Art Discourse

Even today, Praxiteles remains a subject of fascination in art history. His ability to balance realism with idealism continues to inspire discussions about the role of beauty in art. Some modern artists reinterpret his works through a contemporary lens, examining themes of gender, power, and representation that were already subtly present in his sculptures.

(To be continued in Part 3, where we will explore the technical challenges Praxiteles faced, his lesser-known works, and his enduring cultural significance in the modern era.)

The Technical Mastery Behind Praxiteles’ Sculptures

Praxiteles’ genius lay not only in his artistic vision but also in his unparalleled technical skill. His ability to manipulate marble and bronze with such delicacy set him apart from his contemporaries and established techniques that would be studied for millennia.

1. The Challenge of Marble

Working with marble required extraordinary precision. Unlike bronze, which allowed for casting and corrections, marble was unforgiving—every strike of the chisel was permanent. Praxiteles mastered the art of undercutting, creating depth and lightness in details like cascading hair or clinging drapery. His ability to make stone appear weightless, as seen in the flowing robes of his *Aphrodite* statues, demonstrated his unrivaled control over the medium.

2. Innovations in Bronze

Though fewer of his bronze works survive, ancient historians praised them for their dynamic energy. Bronze allowed Praxiteles to experiment with more complex poses, such as figures in mid-motion—something marble often couldn’t support structurally. His bronzes likely employed the hollow-casting technique, reducing material use while maintaining durability.

3. Tools and Workshop Practices

Archaeological evidence suggests Praxiteles’ workshop used drills, rasps, and abrasives to achieve smooth surfaces. His team may have employed pointing techniques (transferring measurements from a model), ensuring consistency in reproductions—a practice later adopted by Roman copyists. Interestingly, traces of pigment on some replicas indicate his sculptures were originally painted, adding lifelike hues to the stone.

Lesser-Known Works and Attributed Pieces

Beyond his famous masterpieces, Praxiteles created numerous sculptures that, while less documented, reveal the breadth of his talent. Many exist today only in fragments or secondhand accounts.

1. The Resting Satyr

This youthful, languid figure—leaning on a tree trunk with a playful expression—exemplifies Praxiteles’ skill in blending relaxation with latent energy. Multiple Roman copies exist, though the original’s location remains unknown.

2. Eros of Thespiae

A celebrated bronze statue housed in Thespiae, it was said to rival the beauty of the *Aphrodite of Knidos*. Ancient writers described Eros’s face as “bewitching,” capturing the god of love in a moment of tender contemplation.

3. The Artemis of Antikyra

A rare depiction of the virgin huntress in a softened, almost introspective pose—far from the rigid Artemis statues of earlier periods. Some scholars debate its attribution, but the delicate drapery work suggests Praxiteles’ influence.

The Mysterious Disappearance of Originals

The scarcity of Praxiteles’ authenticated originals raises enduring questions.

1. Lost to Time and Conflict

Many works likely perished in earthquakes, fires, or the destruction of pagan temples during Christianity’s rise. The *Aphrodite of Knidos* was reportedly moved to Constantinople but vanished after riots in the 5th century CE.

2. The Role of Roman Collectors

Roman elites prized Greek originals, often transporting them to Italy. Over centuries, improperly stored bronzes oxidized into oblivion, while marbles were repurposed as building material.

3. Forgery and Misattribution

The Praxitelean “brand” was so prestigious that later artists falsely credited works to him. Modern spectroscopy helps identify authentic pieces, such as verifying marble from Paros, his preferred quarry.

Sensuality vs. Sacredness: A Cultural Paradox

Praxiteles’ sensual depictions of gods sparked debates about piety versus artistry that still resonate today.

1. Divine Humanity

By showing deities in vulnerable states—Aphrodite bathing, Dionysus as a child—he humanized the divine. Conservative critics accused him of diminishing reverence, while others saw profundity in making gods relatable.

2. The Female Gaze in Ancient Art

The *Aphrodite of Knidos* was groundbreaking not just for its nudity but for its presumed audience: women. Some theories suggest the sculpture’s placement allowed ritual viewing by priestesses, subverting male-dominated artistic narratives.

3. Modern Parallels

Contemporary debates over artistic freedom versus cultural sensitivity mirror ancient tensions around Praxiteles’ work. His legacy reminds us that art’s power lies in its ability to provoke and comfort simultaneously.

Praxiteles in Popular Culture and Scholarship

From museums to movies, echoes of Praxiteles endure.

1. Museum Exhibitions

Recent exhibits, like the Louvre’s *Praxiteles Revisited*, use augmented reality to reconstruct lost works, allowing viewers to “see” originals through Roman copies.

2. Literary References

Novels like *The Sand-Reckoner* fictionalize his rivalry with Phidias, while poets from Ovid to Rilke have drawn inspiration from his sculptures’ emotional depth.

3. Digital Archaeology

Projects like the *Digital Sculpture Project* use laser scans to analyze tool marks, revealing how Praxitelean techniques influenced Roman workshops.

Conclusion: The Eternal Chisel

Praxiteles’ art transcended his era because it spoke to universal truths—the beauty of imperfection, the sacred in the everyday. His fusion of technical mastery and emotional honesty created a bridge between human and divine that still captivates. In museums worldwide, even as Roman copies, his works whisper secrets of marble and meaning, reminding us that true artistry is timeless. Whether through the provocative gaze of the *Aphrodite* or the playful mischief of *Hermes*, his legacy endures: not in stone alone, but in the endless dialogue between artist and observer across the ages.

Comments