Mark Antony: The Rise of a Roman Legend

Early Life and Family Background

Mark Antony was born in 83 BC into a prominent Roman family. His father, Marcus Antonius Creticus, was a praetor who died when Antony was young. His mother, Julia, came from the distinguished Julia gens, making him a relative of Julius Caesar. This noble lineage would play a crucial role in shaping his future.

Antony grew up in a turbulent period of Roman history, witnessing political instability and civil wars. His early years were marked by financial difficulties after his father's death, but his family connections helped him secure opportunities in public life. He received a typical aristocratic education, studying rhetoric and military tactics.

Military Career Beginnings

Antony first gained military experience under Aulus Gabinius in Syria and Egypt. His bravery and leadership skills quickly became apparent, earning him recognition among his peers. He distinguished himself in various campaigns, including the restoration of Ptolemy XII to the Egyptian throne.

These early military successes established Antony's reputation as a capable commander. His ability to inspire loyalty among his troops would become one of his greatest strengths throughout his career. The experience in Egypt also gave him his first exposure to the Ptolemaic dynasty, which would later play a significant role in his life.

Alliance with Julius Caesar

Antony's career took a dramatic turn when he became one of Julius Caesar's most trusted lieutenants during the Gallic Wars. His military prowess and loyalty endeared him to Caesar, who recognized his potential. Antony served as Caesar's cavalry commander and played crucial roles in several battles.

During the civil war between Caesar and Pompey, Antony proved himself indispensable. He commanded Caesar's left wing at the decisive Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BC, where Pompey's forces were defeated. This victory cemented Caesar's power in Rome and elevated Antony's status as one of the most important figures in the Roman Republic.

Political Career in Rome

With Caesar's victory, Antony entered the political arena as one of Rome's most powerful men. He served as Caesar's Master of the Horse (second in command) and later as consul. Antony's political skills were tested as he navigated the complex world of Roman politics, balancing various factions and interests.

However, Antony's time in Rome was not without controversy. His lavish lifestyle and political maneuvers made him enemies among the conservative senators. His relationship with Caesar remained strong, but tensions began to emerge with other members of Caesar's circle, including Octavian, Caesar's adopted heir.

The Ides of March and Aftermath

The assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BC marked a turning point in Antony's life. As consul, he took control of the situation, delivering a famous funeral oration that turned public opinion against the conspirators. Antony skillfully positioned himself as Caesar's political heir, gaining control of his papers and much of his wealth.

In the chaotic aftermath of Caesar's death, Antony found himself in a power struggle with the conspirators and with Octavian. The formation of the Second Triumvirate with Octavian and Lepidus in 43 BC was a strategic move to consolidate power and defeat Caesar's assassins. This alliance would dominate Roman politics for the next decade.

The Battle of Philippi

The Triumvirate's forces met the armies of Brutus and Cassius at Philippi in 42 BC. Antony played a leading role in the campaign, demonstrating his military genius in two decisive battles. The victory at Philippi effectively ended the Republican cause and eliminated the last major opposition to the Triumvirate's rule.

After Philippi, the Triumvirs divided the Roman world among themselves. Antony took control of the eastern provinces, where he would spend most of the next decade. This period marked the beginning of his famous relationship with Cleopatra VII of Egypt, which would have profound consequences for his career and Roman history.

Antony in the East

Antony's administration of the eastern provinces was a mix of successes and controversies. He reorganized client kingdoms, settled veterans, and prepared for campaigns against Parthia. His relationship with Cleopatra became increasingly public, and he acknowledged their children, creating tensions with Rome.

The Parthian campaign of 36 BC proved disastrous, damaging Antony's military reputation. Meanwhile, his relationship with Octavian deteriorated, as both men positioned themselves for a final confrontation. The stage was set for one of the most dramatic conflicts in Roman history, which would determine the future of the Mediterranean world.

Antony and Cleopatra: A Political and Personal Alliance

The relationship between Mark Antony and Cleopatra VII of Egypt was more than a passionate romance—it was a calculated political alliance that reshaped the Mediterranean world. After his defeat at the Battle of Philippi, Antony traveled to the East to secure Rome’s territories and gather resources for future campaigns. It was in Tarsus, in 41 BC, that he first summoned Cleopatra, seeking her support against the Parthian Empire.

Cleopatra, however, was no passive pawn. She arrived in a lavish procession, embodying the goddess Isis, and immediately captivated Antony. Their union combined Egyptian wealth with Roman military power, creating an uneasy but formidable coalition. Over time, their bond deepened into both a personal love affair and a strategic partnership. Antony provided military protection for Egypt, while Cleopatra financed his political ambitions in Rome. Together, they envisioned a Greco-Roman-Egyptian empire that could rival Octavian’s growing dominance.

Yet their relationship scandalized Rome. Antony’s reputed abandonment of Roman virtues in favor of "Eastern decadence" was weaponized by Octavian’s propaganda. When Antony formally recognized Cleopatra’s children—including twins Alexander Helios and Cleopatra Selene—and granted them territories, it fueled accusations of disloyalty to Rome.

The Donations of Alexandria (34 BC): A Fatal Gamble?

A pivotal moment came in 34 BC when Antony staged the so-called **Donations of Alexandria**—a grand ceremony where he declared Cleopatra and Caesarion (her son with Julius Caesar) as rulers of Egypt, Cyprus, and parts of Syria. He also distributed Roman-controlled lands to their children, including Armenia, which he had recently conquered.

This move was politically explosive. To the Roman Senate, it appeared as though Antony was handing over Roman territory to a foreign queen and her heirs. Octavian seized on this, portraying Antony as a traitor who had "gone native" and abandoned Rome for an Egyptian dynasty. The propaganda war intensified, with Octavian positioning himself as the defender of Roman tradition against Antony’s supposed Oriental excesses.

The Breakdown of the Triumvirate

By the mid-30s BC, the alliance between Octavian, Antony, and Lepidus had nearly dissolved. The Triumvirate, initially created to avenge Caesar’s death, had outlived its purpose. Lepidus, the weakest of the three, had already been sidelined. The real struggle was now between Antony and Octavian—two men with competing visions for Rome.

Octavian skillfully undermined Antony’s reputation in Rome, using his alliance with Cleopatra to portray him as an enemy of the Republic. Antony retaliated by accusing Octavian of illegally seizing power and disrespecting Caesar’s legacy. The final rupture came when Octavian obtained Antony’s will (possibly through theft or forgery), which allegedly named Cleopatra’s children as his heirs and requested burial in Egypt. This was the last straw for the Roman elite.

In 32 BC, Octavian declared war—not on Antony, but on Cleopatra, framing the conflict as Rome versus an Eastern threat. The Senate stripped Antony of his titles, and Italy swore an oath of allegiance to Octavian. The stage was set for the definitive clash between East and West.

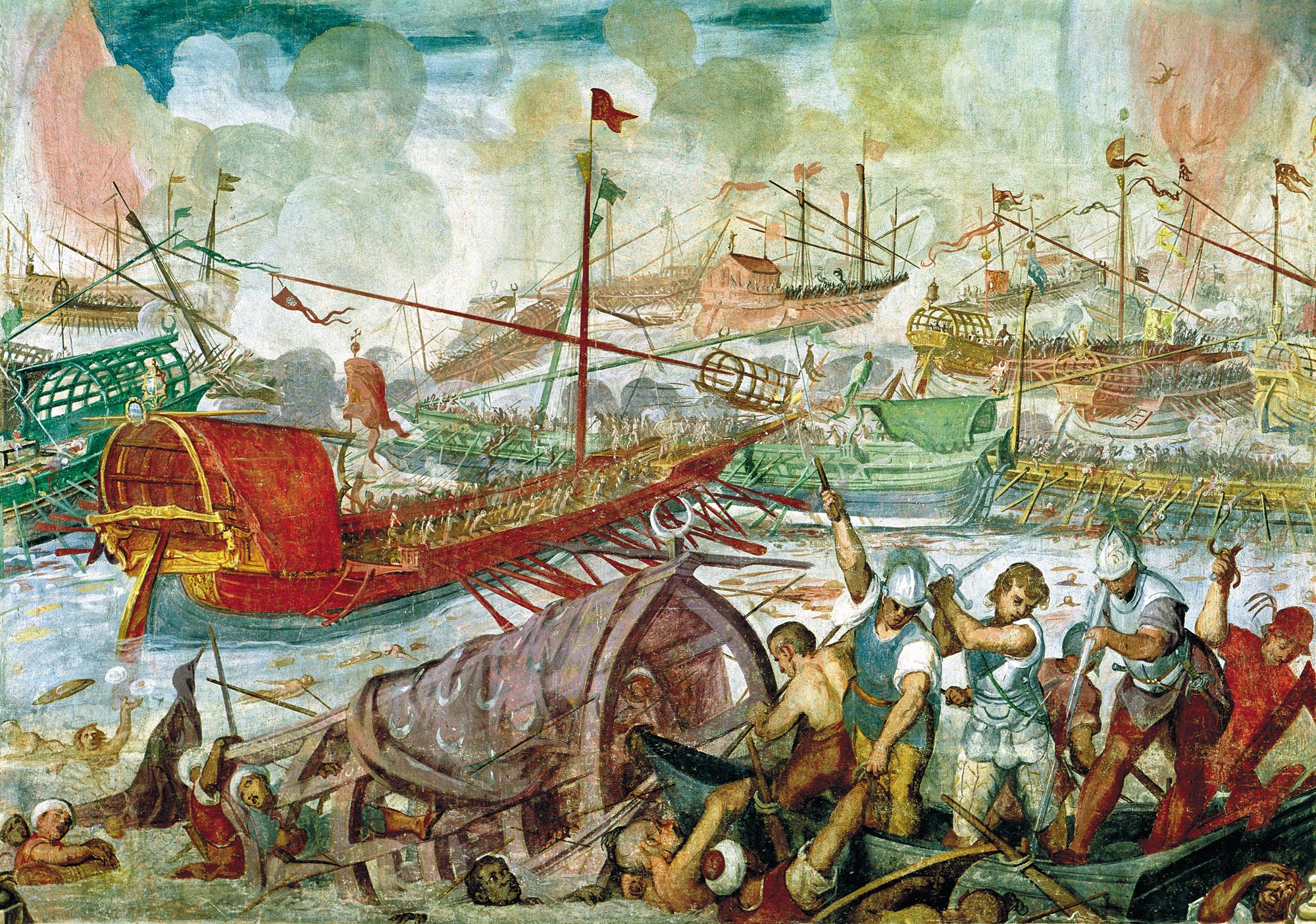

The Battle of Actium (31 BC): Antony's Downfall

The final confrontation took place near **Actium**, Greece, in September 31 BC. Antony and Cleopatra, leading a joint Roman-Egyptian fleet, faced Octavian’s forces under the command of the brilliant general Agrippa. Despite their numerical advantage, Antony’s forces suffered from poor coordination and desertions.

Historians debate whether Cleopatra’s sudden retreat during the battle was a tactical blunder or a premeditated decision. Regardless, Antony followed her, abandoning his fleet, which soon surrendered. The defeat was catastrophic, scattering their forces and leaving Egypt vulnerable.

The Last Stand in Alexandria

After Actium, Octavian pursued Antony and Cleopatra back to Alexandria. Instead of surrendering, Antony attempted a final, desperate resistance, but his remaining legions defected to Octavian. Believing Cleopatra had died (after a false rumor spread), Antony fell on his sword—only to later learn she was still alive. He was brought to her, where he died in her arms.

Cleopatra, facing the prospect of being paraded in Rome as a captive, committed suicide shortly afterward, possibly via an asp bite. With their deaths, Octavian became the undisputed ruler of Rome. He consolidated power, later taking the name **Augustus**, and transformed the Republic into the Roman Empire.

Legacy: The Posthumous Vilification of Antony

In death, Antony became a cautionary tale in Roman politics. Octavian (now Augustus) ensured that history remembered him as a once-great general who had been corrupted by power and foreign influence. Roman writers, most notably **Virgil** and **Horace**, portrayed him as a slave to Cleopatra’s seduction, a man who had forsaken Rome for a doomed love affair.

Yet historians today recognize Antony’s complex legacy. He was a brilliant military strategist, a charismatic leader, and a key figure in Rome’s transition from Republic to Empire. His romance with Cleopatra, though politically costly, remains one of history’s most legendary love stories. Modern interpretations, from Shakespeare’s *Antony and Cleopatra* to Hollywood depictions, have immortalized his dramatic life—often emphasizing the tragedy of a man torn between duty and passion.

But beyond myth, Antony’s career raises enduring questions about loyalty, ambition, and the cost of power. Was he truly a traitor to Rome, or merely a victim of Octavian’s ruthless rise? Did Cleopatra manipulate him, or did they share a genuine partnership? These debates continue to fascinate historians and storytellers alike.

Next: Military Tactics, Personal Rivalries, and How History Judges Antony

The final section of this biography will examine Antony’s battlefield strategies, his rivalry with Octavian, and how modern scholarship evaluates his role in Roman history. Did his flaws outweigh his achievements? And how did his downfall shape the Roman Empire’s future?

Military Tactics and Leadership: The Art of War According to Antony

Mark Antony’s military career was marked by bold strategies, tactical brilliance, and a deep understanding of battlefield psychology. His campaigns, from Gaul to Egypt, showcased his ability to adapt to different terrains and enemies. Unlike many Roman generals of his time, Antony preferred aggressive, decisive engagements rather than prolonged sieges. His leadership style was charismatic—he often fought alongside his troops, earning their loyalty through personal bravery.

One of his most famous military feats was the **Battle of Philippi** (42 BC), where he outmaneuvered Brutus and Cassius despite being outnumbered. His ability to exploit the terrain and coordinate cavalry charges was instrumental in securing victory. However, his later campaigns, particularly the disastrous **Parthian War** (36 BC), revealed his strategic overreach. Antony underestimated the logistical challenges of fighting in the desert, leading to heavy losses.

Historians debate whether Antony’s military failures were due to poor planning or external factors. Some argue that his reliance on Cleopatra’s financial support made him vulnerable, while others point to his tendency to prioritize personal glory over long-term strategy. His rivalry with Octavian also played a role—Antony’s focus on Eastern campaigns left him politically isolated in Rome.

Antony vs. Octavian: A Clash of Visions

The competition between Antony and Octavian was not just a power struggle—it was a battle for Rome’s future. Octavian represented the disciplined, bureaucratic approach to governance, while Antony embodied the old Roman ideal of the warrior-statesman. Their rivalry escalated into a propaganda war, with Octavian painting Antony as a traitor corrupted by Cleopatra, and Antony accusing Octavian of betraying Caesar’s legacy.

The **Perusine War** (41–40 BC) was a turning point. Antony’s wife, Fulvia, and brother, Lucius, led a rebellion against Octavian, but their defeat weakened Antony’s position. Though he later reconciled with Octavian (via the Treaty of Brundisium), the alliance was fragile. By the time of Actium, their relationship had deteriorated beyond repair.

How History Remembers Antony: Hero or Villain?

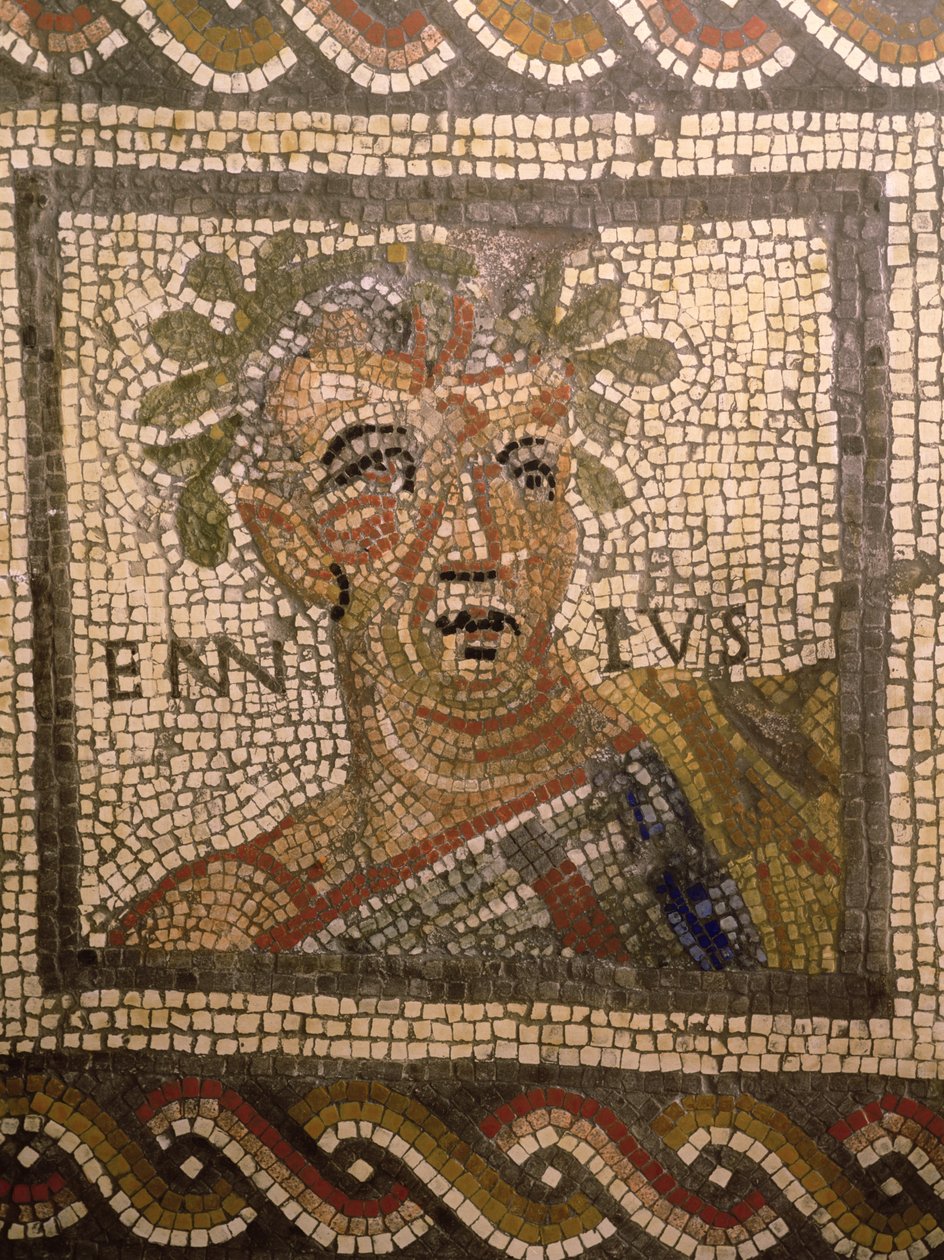

For centuries, Roman historians—largely influenced by Augustan propaganda—depicted Antony as a tragic figure who succumbed to vice. **Plutarch**, in *Life of Antony*, portrayed him as a man of contradictions: brave yet reckless, loyal yet easily swayed. Modern historians, however, offer a more nuanced view.

Recent scholarship suggests that Antony was a skilled politician who understood the importance of spectacle and loyalty. His alliance with Cleopatra was not just romantic but strategic—an attempt to create a Mediterranean superpower. His downfall was less about personal failings and more about the unstoppable rise of Octavian’s political machine.

Antony’s Cultural Legacy

From Shakespeare to Hollywood, Antony’s story has been retold countless times. **Shakespeare’s *Antony and Cleopatra*** immortalized him as a tragic hero, torn between love and duty. In film, actors like Richard Burton (*Cleopatra*, 1963) and James Purefoy (*Rome*, 2005) have brought his charisma to life.

Beyond entertainment, Antony’s life raises timeless questions:

- **Can love and power coexist?** His relationship with Cleopatra blurred the line between personal and political.

- **What is the cost of ambition?** His relentless pursuit of glory led to his undoing.

- **How does history judge losers?** Despite his defeat, his legacy endures.

Conclusion: The Man Behind the Myth

Mark Antony was neither a flawless hero nor a one-dimensional villain. He was a product of his time—a brilliant general, a flawed politician, and a man who dared to challenge Rome’s status quo. His alliance with Cleopatra, though ultimately doomed, reshaped the ancient world. His rivalry with Octavian marked the end of the Republic and the birth of the Empire.

In the end, Antony’s story is a reminder that history is written by the victors—but not always fairly. His legacy, like Rome itself, is complex, contradictory, and endlessly fascinating.

**Final Thought:**

*"Fortune favors the bold,"* wrote Virgil. Antony lived by this creed—and perished by it. His life remains a testament to the power of ambition, the weight of choices, and the price of greatness.

/image%2F0994950%2F20231227%2Fob_6ee823_oip-le9zan7rfdbd9et6yb3f1whaet-w-246-h.7)

Comments