Marcus Junius Brutus: The Noble Conspirator

Early Life and Lineage

Marcus Junius Brutus, often simply called Brutus, remains one of history’s most complex and controversial figures. Born around 85 BCE into an aristocratic Roman family, Brutus was deeply influenced by his lineage and the political turmoil of his time. His father, also named Marcus Junius Brutus, was a tribune of the plebs and a supporter of the populist leader Marius, but he was later executed by Pompey the Great during the civil wars. His mother, Servilia, was a powerful and politically connected woman, famously rumored to have been the mistress of Julius Caesar.

Brutus was raised in an environment steeped in Republican ideals, with his uncle Cato the Younger serving as a prominent Stoic philosopher and staunch defender of the Roman Republic. These influences shaped Brutus’s moral and political outlook, instilling in him a deep respect for tradition, liberty, and the Senate’s authority.

Education and Early Career

Brutus received an elite education, studying rhetoric, philosophy, and law. His early adulthood coincided with the decline of the Republic, as powerful figures like Julius Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus vied for dominance. Initially, Brutus aligned himself with Pompey during Caesar’s civil war, fighting against Caesar at the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BCE. Despite this, Caesar pardoned Brutus, possibly due to his mother’s influence, and even appointed him to positions of trust, including the governorship of Cisalpine Gaul.

Brutus’s relationship with Caesar was complicated. While he benefited from Caesar’s patronage, his loyalty to the Republic and his philosophical convictions increasingly clashed with Caesar’s expanding power.

The Conspiracy Against Caesar

By 44 BCE, Caesar had been declared dictator perpetuo (dictator for life), a title that alarmed traditionalists like Brutus. Though Brutus had initially supported Caesar’s reforms, he grew fearful that Caesar’s ambitions threatened the Republic’s very existence. Alongside his brother-in-law Gaius Cassius Longinus and other senators, Brutus became a leading figure in the conspiracy to assassinate Caesar.

The motives behind Brutus’s involvement remain debated. Some historians argue that personal ambition played a role, while others believe he acted out of genuine republican idealism. His philosophical education and family legacy likely reinforced his belief that Caesar’s death was a necessary sacrifice to restore Rome’s constitutional government.

The Ides of March

On March 15, 44 BCE, Brutus and his fellow conspirators carried out their plan. They lured Caesar to the Senate, where they attacked him with daggers. Shakespeare famously dramatized this moment, portraying Caesar’s shock upon seeing Brutus among his killers with the line, “Et tu, Brute?” (“You too, Brutus?”). Whether these words were actually spoken remains uncertain, but they capture the betrayal’s symbolic weight.

The aftermath of the assassination was chaotic. Instead of restoring the Republic, the act plunged Rome into further instability. The conspirators, expecting to be hailed as liberators, were met with mixed reactions. While some Romans supported them, others, particularly Caesar’s veterans and the urban poor, were outraged.

Brutus’s Downfall and Legacy

Mark Antony and Octavian (later Augustus) quickly turned public sentiment against the conspirators. Forced to flee Rome, Brutus and Cassius gathered an army in the East. Their hopes of preserving the Republic were crushed at the Battle of Philippi in 42 BCE, where they were defeated by Antony and Octavian’s forces. Rather than be captured, Brutus committed suicide, signaling the end of the old Republican order.

Brutus’s legacy remains a subject of debate. To some, he is a tyrannicide who acted for the greater good; to others, he is a betrayer whose actions led to Rome’s descent into imperial rule. His life and choices continue to inspire discussions about morality, power, and the fragility of republics.

This concludes the first part of the article on Marcus Junius Brutus. Proceed to the next prompt to continue.

Brutus' Philosophy and Moral Dilemma

Marcus Junius Brutus was not merely a politician or a soldier—his actions were deeply rooted in philosophical convictions, particularly Stoicism. He was a disciple of Stoic philosophy, a way of thinking that emphasized virtue, duty, and self-control. His uncle, Cato the Younger, had been an uncompromising Stoic who chose suicide over surrender to Julius Caesar, reinforcing Brutus’ belief in principles over personal survival.

However, Brutus’ decision to join the conspiracy posed an ethical dilemma: was assassination justified to save the Republic? Roman tradition permitted extreme measures against tyrants, but the murder of a man who had spared and even promoted Brutus was a heavy moral burden. Cicero, though not a conspirator, expressed admiration for Brutus’ motives, calling the act "glorious." Yet, even among his peers, questions lingered—had Brutus acted out of necessity or idealism taken too far?

Brutus in Exile: The Final Campaign

After Caesar’s assassination, Brutus and Cassius fled Rome, recognizing that their lives were in danger. They mobilized forces in Greece and Asia Minor, recruiting legions and accumulating wealth to sustain their war effort. Despite facing logistical challenges and wavering loyalty among some allies, Brutus led with discipline, earning respect as an honorable commander—albeit one fighting a losing cause.

In 42 BCE, the forces of the Second Triumvirate (Octavian, Mark Antony, and Lepidus) met Brutus and Cassius at Philippi. The two battles fought there would decide the fate of the Republic. In the first clash, Brutus defeated Octavian’s legions, though his camp was overrun, leading to tense uncertainty. Cassius, misinformed and believing the battle lost, tragically took his own life. Days later, a second battle ensued, and this time Brutus’ forces were overwhelmed.

Cornered and aware that both political and military defeat were certain, Brutus chose suicide, reportedly saying, "Virtue exists only in theory—in reality, it is nothing." His final moments encapsulated the Stoic resignation to fate, even as the Republic he sought to preserve crumbled around him.

Brutus in Literature and Popular Memory

Brutus’ legacy extends beyond history into literature and political thought. William Shakespeare immortalized him in *Julius Caesar*, portraying him as a tragic hero torn between loyalty to Rome and personal bonds. The play’s famous funeral speeches—Brutus’ justification of the assassination versus Mark Antony’s masterful manipulation of public grief—highlight the struggle between republican ideals and charismatic tyranny.

Dante Alighieri, in *The Divine Comedy*, placed Brutus and Cassius in the lowest circle of Hell, condemned as traitors alongside Judas Iscariot. In stark contrast, later Enlightenment thinkers like Voltaire and the American Founding Fathers admired Brutus as a martyr for liberty, drawing parallels between Caesar’s tyranny and monarchical abuses of power.

The question of whether Brutus acted nobly or infamously remains unresolved. Was he the last defender of Rome’s liberty or a shortsighted assassin whose actions hastened the Empire?

The Personal Life of Brutus

Behind Brutus the conspirator was a man with personal loyalties and conflicts. His marriage to Porcia, Cato’s daughter, was one of deep intellectual and political kinship. Ancient sources, particularly Cicero and Plutarch, depict her as fiercely devoted—even wounding herself to prove she could endure hardship alongside her husband. Some accounts suggest she may have taken her own life upon hearing of Brutus' death, though historical evidence is scarce.

His relationship with Caesar was even more complicated. Despite Caesar’s affair with Brutus’ mother and his political ruthlessness, he had shown Brutus unusual favor. Rumors even circulated that Brutus may have been Caesar’s illegitimate son—though most historians dismiss this as later sensationalism. Whatever the case, Brutus’ decision to strike down a man who had spared him added a layer of personal betrayal to his act.

Military and Political Strategy: A Flawed Leader?

While Brutus was respected for his honor, some historians argue that his leadership was flawed. His hesitations before the assassination—debating whether to kill Mark Antony alongside Caesar—proved costly, allowing Antony to rally public sentiment. Similarly, while he was a competent general, his conservative tactics at Philippi contrast with the daring maneuvers of Caesar or Antony, suggesting a reluctance to adapt.

Moreover, Brutus’ idealism often clashed with political reality. Unlike Cassius, who was more pragmatic, Brutus insisted on treating defeated enemies with mercy—a noble stance that sometimes undermined his cause. His refusal to seize funds from provincial cities without "just" taxation, for instance, weakened his war chest before Philippi.

Continue to the final part of the article to explore the lasting historical debates, modern interpretations, and Brutus’ influence on political thought.

Brutus Through the Lens of History: Debates and Interpretations

The historical assessment of Marcus Junius Brutus has fluctuated dramatically over the centuries, reflecting changing attitudes toward power, republicanism, and political violence. Ancient historians like Plutarch presented him as a complex figure torn between noble intentions and tragic flaws, while later Roman imperial historians often vilified him to justify the Augustan regime's legitimacy. Modern scholarship continues to wrestle with his legacy, unable to reach consensus on whether he was a principled patriot or a misguided idealist.

One persistent debate centers on Brutus' motivations. Some scholars argue his actions sprang from genuine philosophical conviction, noting his extensive writings on virtue (now lost) and his adherence to Stoic principles. Others point to political ambition - his rivalry with Caesar, his association with Pompey's faction, and his desire to restore his family's prominence after his father's execution. The truth likely lies somewhere between these extremes, as with most historical figures of his stature.

The Death of the Republic: Was Brutus Responsible?

A central question in Roman historiography is whether Brutus' assassination of Caesar accidentally doomed the very republic he sought to save. Had he allowed Caesar to rule, might the republican facade have remained intact longer? Or was Caesar's dictatorship already an irreversible step toward monarchy? Cicero's letters reveal contemporary doubts among Rome's elite about the conspiracy's effectiveness even before its execution.

Ironically, the republic's collapse may have validated Brutus' fears about centralized power. The Augustan principate that emerged from Rome's civil wars created precisely the permanent autocracy Brutus had hoped to prevent. This historical irony has made him a recurring symbol in political philosophy about the limits of resistance to tyranny.

Military Leadership Re-examined

Modern military historians have re-evaluated Brutus' campaigns with mixed conclusions. While his ethical approach to warfare was admirable by Roman standards, his rigid adherence to traditional tactics at Philippi may have cost him victory. Unlike Caesar, who innovated constantly, Brutus preferred conventional set-piece battles - a disadvantage against Mark Antony's more flexible command style.

His naval victory at the Battle of Rhodes in 42 BCE demonstrates his capability when forced to innovate, suggesting his conservatism at Philippi might reflect philosophical principles rather than military incompetence. Some scholars argue that, given adequate resources and time, Brutus might have developed into a commander of Caesar's caliber.

The Psychological Portrait: Brutus' Inner Conflicts

Recent scholarship has employed psychological analysis to understand Brutus' decision-making. His well-documented insomnia and reported visions of Caesar's ghost (accounts possibly exaggerated by later sources) suggest a man psychologically tortured by his actions. This contrasts with Shakespeare's composed, philosophical Brutus and supports interpretations of a more conflicted personality.

His correspondence with Cicero reveals moments of self-doubt rare among Roman aristocrats. A recently rediscovered papyrus fragment contains what may be Brutus' own words: "I act not for myself, but for Rome; yet Rome does not thank me." This personal anguish makes him a compelling figure for modern biographers.

Cultural Legacy: From Dante to Modern Democracy

Brutus' cultural afterlife has been remarkably varied. Dante famously placed him in the lowest circle of Hell for betraying Caesar, while Renaissance republican thinkers like Machiavelli praised him as a model of civic virtue. The American Founding Fathers invoked Brutus as both cautionary tale and inspiration - Jefferson reportedly kept busts of Brutus alongside other republican heroes.

In modern popular culture, Brutus has become shorthand for political betrayal while simultaneously representing principled resistance. This dichotomy appears vividly in contemporary political rhetoric, where opposing sides frequently accuse each other of "Brutus-like" treachery or celebrate "Brutus moments" against modern authoritarians.

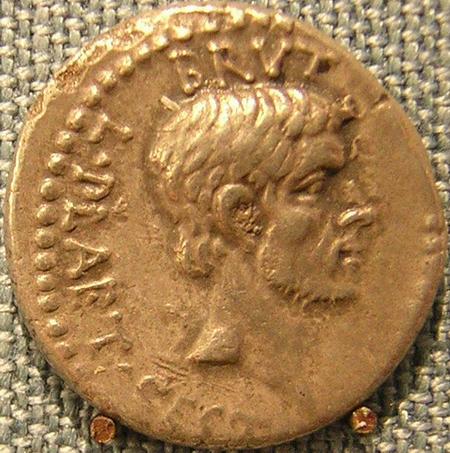

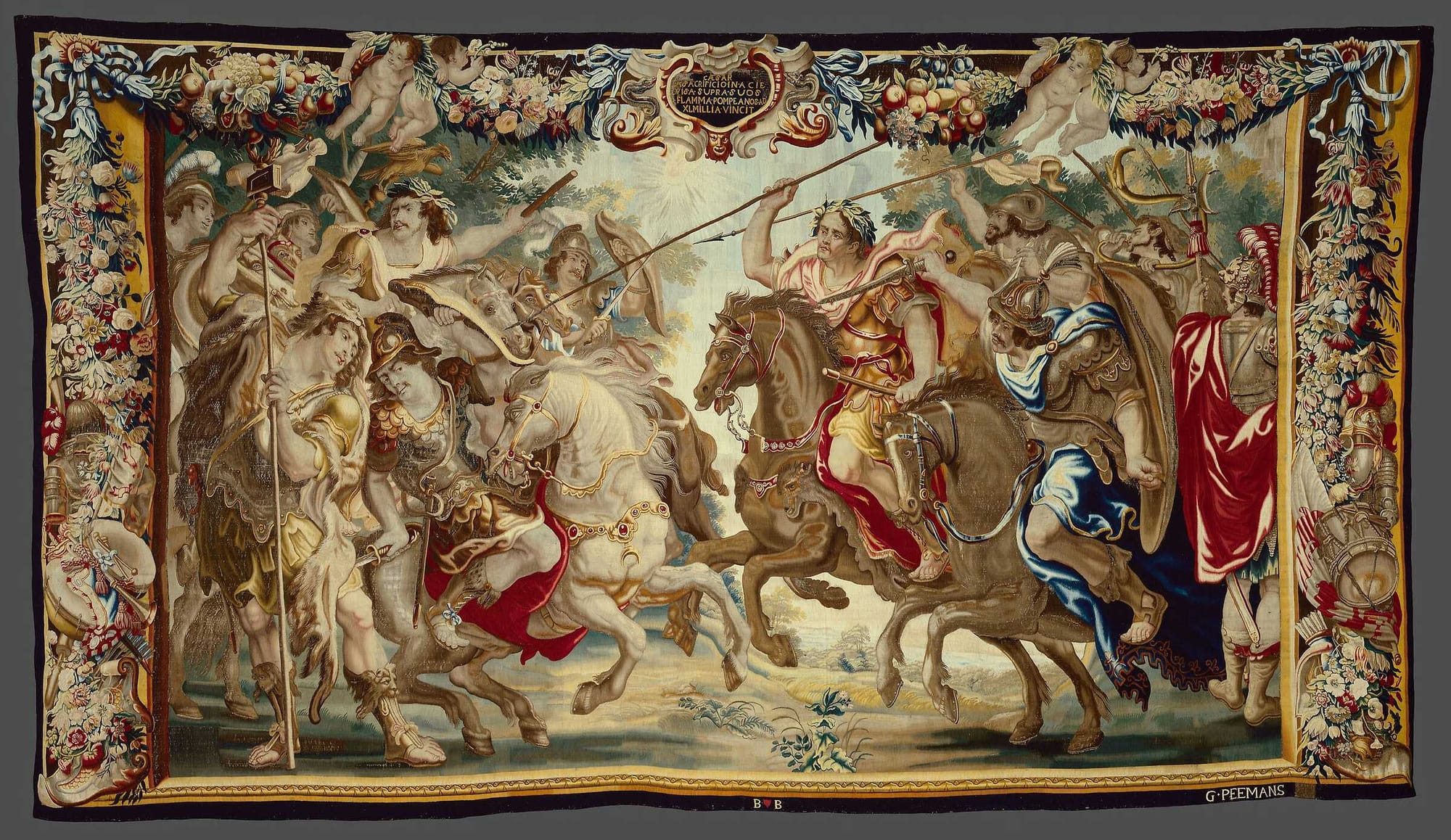

The Material Evidence: Coins and Artifacts

Archaeological discoveries continue to shed new light on Brutus. His famous "Ides of March" coin, minted in 42 BCE, remains one of antiquity's most politically charged artifacts. Featuring his portrait alongside two daggers and a liberty cap, it represents one of history's first uses of coinage as propaganda.

Recent excavations at Philippi have uncovered what may be remnants of Brutus' camp, including styluses and writing tablets that hint at his administrative style. A 2018 British Museum exhibition controversially displayed a dagger claimed (though not verified) to be one of the actual weapons used in Caesar's assassination.

Modern Political Parallels

In an era of democratic backsliding and rising authoritarianism, Brutus' dilemma has gained new relevance. Political theorists debate whether his example sanctions extra-constitutional action against dictators or warns against the unintended consequences of political violence.

Comparisons have been drawn between Brutus' Rome and contemporary threats to democratic institutions worldwide. The essential question remains: when, if ever, is the violent removal of a populist leader justified to preserve democratic norms? Brutus' story offers no easy answers but provides a framework for this perennial debate.

Final Judgment: Tyrant or Patriot?

Two millennia after his death, Marcus Junius Brutus continues to defy simple categorization. He embodied the contradictions of his time - a man of high principle who committed murder, a defender of law who broke sacred traditions, an aristocrat who championed republicanism. Perhaps his most enduring lesson is that political actions, even those undertaken with the noblest intentions, can produce unforeseen and irreversible consequences.

As historian Mary Beard observes, "Brutus reminds us that history's verdicts are never final, and that today's hero may be tomorrow's villain - and vice versa." In an age when political and moral certainties increasingly appear elusive, Brutus' complex legacy serves as both warning and inspiration for those who would seek to balance ideals with the messy realities of governance.

Comments