Maecenas: The Influential Patron of the Augustan Age

The Life and Legacy of Gaius Maecenas

Gaius Maecenas, a name synonymous with artistic patronage, was a wealthy Roman statesman and diplomat who played a pivotal role in shaping the cultural landscape of the Augustan Age. Born around 70 BCE into an aristocratic Etruscan family, Maecenas rose to prominence as a close confidant of Emperor Augustus, using his influence and resources to support the greatest poets and writers of his time. His legacy as a benefactor of the arts endures to this day, with the term "maecenas" now commonly used to describe generous patrons of culture and literature.

Early Life and Political Career

Little is known about Maecenas' early years, but historical records indicate he came from a noble Etruscan lineage that claimed descent from the ancient kings of Rome. His family's wealth and status provided him with the means to establish himself in Roman political circles. As civil wars tore through the late Republic, Maecenas aligned himself with Octavian (later Augustus), forming a bond that would shape both men's futures.

During the turbulent years following Julius Caesar's assassination, Maecenas emerged as one of Octavian's most trusted advisors. He played crucial diplomatic roles, including negotiating the marriage between Octavian and Scribonia to seal an alliance with Sextus Pompey. His political acumen and discretion made him invaluable to the future emperor, though Maecenas notably never sought official political titles for himself, preferring to operate behind the scenes.

Maecenas as Augustus' Advisor

As Augustus consolidated power and transformed the Roman Republic into an empire, Maecenas served as a key administrator. For nearly a decade (approximately 36-27 BCE), he essentially governed Rome and Italy while Augustus was away on military campaigns. His ability to maintain stability and order during this period demonstrates his political skill and the trust Augustus placed in him.

The Diplomat and Problem Solver

Maecenas was frequently called upon to handle delicate diplomatic situations. When relations between Octavian and Mark Antony deteriorated, Maecenas helped negotiate the important Treaty of Tarentum in 37 BCE, which temporarily preserved their alliance. Even after Augustus became emperor, Maecenas continued to advise on foreign policy and domestic affairs, though his influence waned in later years due to political intrigues surrounding the imperial succession.

Patronage of the Arts

While Maecenas' political contributions were significant, it is his cultural legacy that cemented his place in history. Recognizing the importance of art and literature in legitimizing and celebrating the new Augustan regime, Maecenas assembled an extraordinary circle of writers who would produce some of the most enduring works of Latin literature.

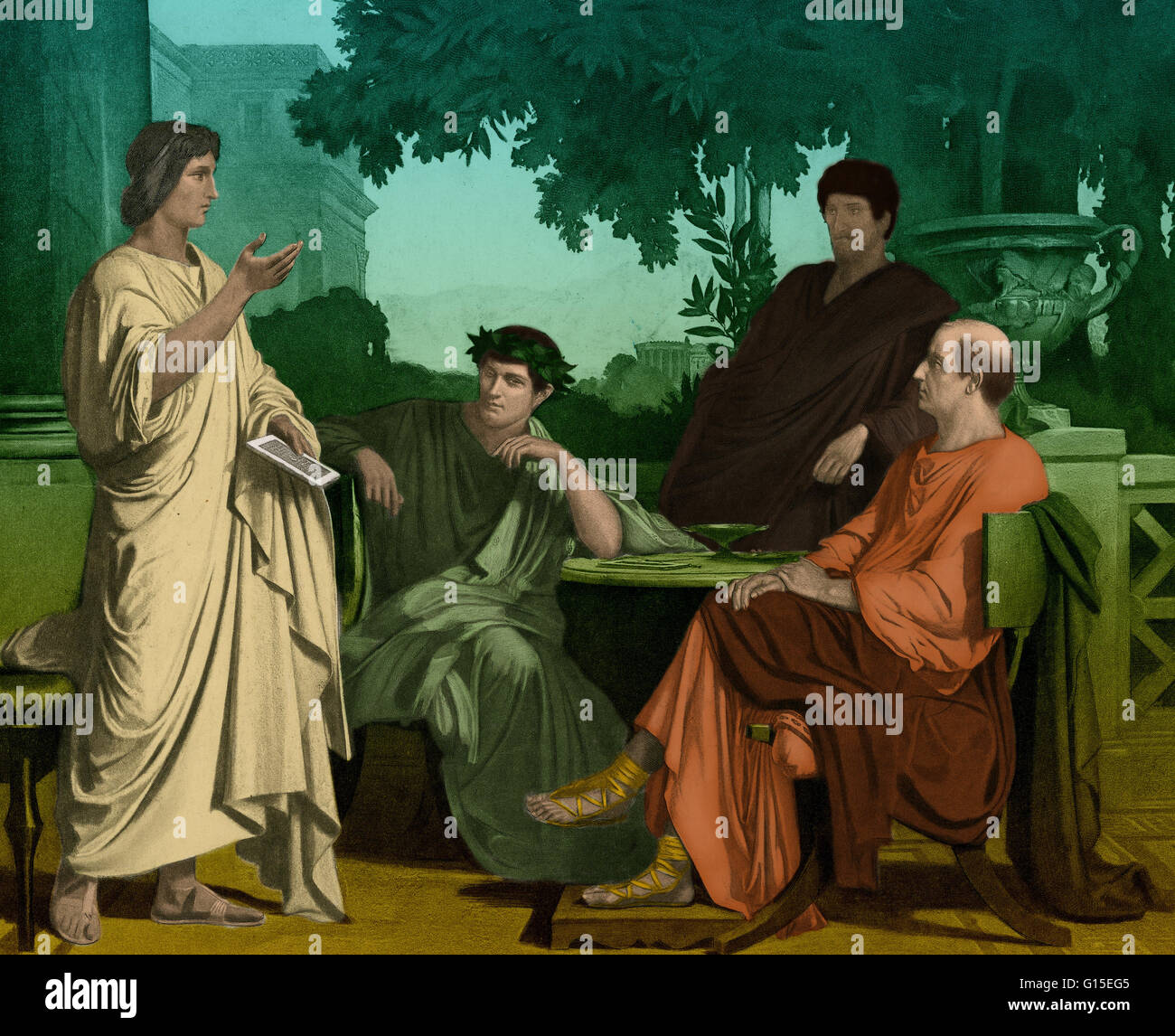

The Augustan Literary Circle

Maecenas' patronage was not merely financial support; he provided a stimulating intellectual environment where poets could thrive. His estate on the Esquiline Hill became a hub of literary activity, where writers exchanged ideas and refined their craft. His approach to patronage was both generous and discreet - he provided material support without demanding overt political propaganda in return.

His circle included luminaries such as Virgil, Horace, and Propertius, whose works helped shape Latin literature and define the cultural achievements of Augustus' reign. This deliberate cultivation of artistic talent served to burnish the image of the new imperial regime while advancing Roman literary culture to new heights.

Virgil and the Aeneid

Maecenas' most famous protegé was undoubtedly Publius Vergilius Maro (Virgil). He likely introduced Virgil to Augustus and supported the poet throughout his career. Virgil's magnum opus, the Aeneid, became the national epic of Rome, linking Augustus' rule to the legendary past and providing ideological support for the new political order. The poem's emphasis on duty, piety, and Rome's divine destiny aligned perfectly with Augustus' vision for Roman society.

Horace: From Freedman's Son to Celebrated Poet

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (Horace) represents another success story of Maecenas' patronage. The son of a freedman, Horace might have struggled to establish himself without Maecenas' support. After introducing him to Augustus, Maecenas gifted Horace a farm in the Sabine hills, providing the poet with financial security and the perfect environment to write. Horace's odes and satires, often dedicated to his patron, remain masterpieces of Latin literature.

Maecenas' Influence on Augustan Cultural Policy

Beyond supporting individual artists, Maecenas helped shape the broader cultural policies of the Augustan Age. Recognizing that art could serve political ends while maintaining aesthetic integrity, he fostered an environment where literature flourished without becoming mere propaganda. This delicate balance contributed to the enduring quality of Augustan literature, which continues to be admired centuries later.

His influence extended to architectural projects and public works as well. The Augustan building program, which transformed Rome from a city of brick to marble, benefitted from Maecenas' guidance. His own estate on the Esquiline Hill was renowned for its elegance and gardens, setting standards for elite residential architecture.

The Personal Life of Maecenas

Contemporaries described Maecenas as a man of refined tastes and sometimes controversial habits. His luxurious lifestyle and fashionable dress attracted criticism from more conservative Romans. He married Terentia, a beautiful woman whose purported affairs became the subject of gossip in Roman society. Despite these personal challenges, Maecenas maintained his position at court until his final years.

As Augustus centralized power and began planning for succession, Maecenas' influence gradually declined. The exact circumstances of his fall from favor remain unclear, though ancient sources suggest his wife may have been involved in court intrigues. He died in 8 BCE, leaving behind no heirs but an unparalleled cultural legacy.

The Enduring Concept of the Maecenas

The model of patronage established by Maecenas became the gold standard for supporting the arts. His approach - identifying talent, providing sustained support, and allowing creative freedom - proved remarkably effective. While many rulers and wealthy individuals have patronized artists throughout history, few have matched Maecenas' combination of generosity, discernment, and lasting impact.

Today, cultural benefactors across the world are still referred to as "maecenases," a testament to his lasting influence. The link between wealth, power, and artistic creation that he embodied continues to shape how societies support their cultural heritage.

Maecenas' Impact on Roman Literary Culture

The circle of writers supported by Maecenas didn't merely produce great works—they fundamentally transformed Latin literature and established canonic forms that would influence Western literature for centuries. This cultural flowering, often called the "Golden Age of Latin Literature," owes much to Maecenas' discerning patronage and his ability to create an environment where artistic innovation could thrive under imperial favor without sacrificing artistic integrity.

Fostering Literary Innovation

Maecenas demonstrated exceptional judgment in identifying poets whose talents could both shape literary culture and subtly advance Augustus' political agenda. Unlike crude propagandists, the poets in his circle approached their themes with nuance and artistry. Virgil's Georgics, for instance, celebrated rural Italian life while promoting Augustus' agricultural policies, yet its poetic excellence transcended its contemporary political context.

Horace's Carmen Saeculare, commissioned for Augustus' Secular Games in 17 BCE, similarly fulfilled an official function while achieving lasting artistic merit. This ability to balance political purpose with poetic excellence was characteristic of Maecenas' approach to patronage—he understood that lasting influence required works that surpassed immediate utilitarian goals.

The Mechanics of Maecenas' Patronage

Modern scholars have pieced together how Maecenas' patronage system operated. Unlike earlier Roman aristocratic patrons who supported clients in exchange for direct services, Maecenas offered support without overt demands. His gifts often took forms that enabled creative work—country estates, financial stipends, access to elite circles, and particularly precious gifts like the famed wine jars he sent to Horace.

The Sabine Farm: A Model of Patronage

Horace's Sabine farm, gifted by Maecenas around 33 BCE, exemplifies this sophisticated approach. Located about 30 miles northeast of Rome in the valley of the Licenza river, this property provided Horace with economic independence (yielding about 80,000 sesterces annually) and an idyllic retreat from urban life. In his Satires and Epistles, Horace describes the farm as a sanctuary where he could write free from distraction, yet close enough to Rome to maintain his connections.

Archaeological excavations at what is believed to be Horace's villa reveal a modest but comfortable estate with a working farm, baths, and quarters for writing—physical evidence of the material conditions Maecenas provided to foster creativity. This model of patronage proved so effective that it inspired later Roman emperors and Renaissance patrons alike.

Political Dimensions of Literary Patronage

While avoiding heavy-handed propaganda, Maecenas' circle did contribute to Augustus' cultural program. Several key themes emerged in their works that aligned with Augustan policies: celebration of Roman origins (Virgil's Aeneid), praise of rural Italian virtues (Virgil's Georgics), and promotion of traditional Roman values (Horace's Odes). These works helped legitimize Augustus' rule by connecting it to Roman tradition while skillfully avoiding clumsy flattery that might undermine their literary credibility.

The Subtle Art of Political Poetry

Examining Horace's work reveals sophisticated engagement with Augustan ideology. His Odes 3.14 celebrating Augustus' return from Spain in 24 BCE manages to praise the emperor while maintaining poetic independence. Similarly, Virgil's depiction of Aeneas in the Aeneid provided Augustus with a mythical ancestor whose qualities of piety and leadership mirrored those Augustus wished to project. Maecenas demonstrated remarkable skill in facilitating this cultural production that served political ends without compromising artistic quality—a balancing act few patrons have achieved so successfully.

Other Figures in Maecenas' Circle

While Virgil and Horace remain the most famous beneficiaries of Maecenas' patronage, his literary circle included other significant figures:

Propertius and Elegiac Poetry

The elegiac poet Sextus Propertius came to Maecenas' attention after publishing his first book of poems around 29 BCE. Though Propertius belonged to the circle and received patronage, his relationship with Maecenas appears more ambivalent than that of Virgil or Horace. His later poems (Books 3 and 4) show increasing engagement with national themes, possibly reflecting Maecenas' influence, though he never abandoned his hallmark erotic elegy style.

The Lost Voices

Ancient sources mention other writers supported by Maecenas whose works haven't survived, including Varius Rufus (who reportedly helped edit the Aeneid after Virgil's death), Domitius Marsus, and other lesser-known poets. The very loss of these works serves as a reminder of how much of ancient literature has disappeared, making Maecenas' successful cultivation of Virgil and Horace all the more significant to literary history.

Maecenas' Own Literary Pursuits

Less known today is that Maecenas himself wrote prose and possibly poetry. Ancient commentators mention his literary efforts, though with mixed reviews—Seneca the Younger criticized his affected style as "degenerate," while Tacitus noted his talent for writing state documents. Whatever their quality, his own literary attempts suggest a genuine personal engagement with the creative process that went beyond mere patronage.

Fragments of his prose works reveal an interest in eccentric topics like gemstones and fish, while some surviving verses display a distinctly unconventional style. This hands-on involvement with writing likely gave him special insight when evaluating others' work and may explain why he proved such an effective patron.

Financial Foundations of Maecenas' Patronage

The scale of Maecenas' cultural investments raises questions about their economic basis. As a wealthy Etruscan aristocrat, he inherited significant property, but his position as Augustus' advisor and the informal "minister of culture" would have brought additional resources. His privileged access to imperial favors and possibly a share of war booty after Actium provided means to fund his patronage activities.

The Economics of Literary Support

In Roman society, where few mechanisms existed for writers to profit directly from their works, patronage was essentially obligatory for serious literary production. Maecenas' system differed from others in its scale and sophistication. While exact figures are unavailable, Horace's Sabine farm likely represented a gift worth several hundred thousand sesterces—a sum comparable to the annual incomes of mid-level senators. Spread across multiple writers over decades, the total investment would have been enormous by ancient standards.

Maecenas and Augustan Propaganda

Modern scholars debate to what extent Maecenas consciously directed his circle's output toward supporting Augustus' regime. Earlier 20th century views tended to see the Augustan poets as essentially propagandists, while more recent scholarship emphasizes their creative independence. The truth likely lies between—Maecenas evidently created conditions where artists could produce work that aligned with Augustan interests without feeling constrained to produce blatant propaganda.

A New Model of Cultural Patronage

What set Maecenas apart was his understanding that cultural influence couldn't be commanded—it had to be cultivated. Rather than demanding specific works or themes, he supported talented writers whose natural inclinations tended toward subjects and values that complemented Augustus' reforms. This subtle approach resulted in literature that served political purposes while achieving artistic greatness—a rare combination in state-sponsored art.

The Decline of Maecenas' Influence

In his later years, Maecenas' position at Augustus' court began to wane, marking the gradual end of an extraordinary period of cultural patronage. Ancient sources suggest several factors contributed to this decline, including political intrigues surrounding the imperial succession and concerns about Maecenas' wife Terentia's alleged indiscretions. By 16 BCE, his role had diminished significantly, with power shifting to Agrippa and others in Augustus' inner circle.

A Changing Political Landscape

As Augustus consolidated his principate, the informal governance structures of the early years gave way to more formal administrative systems. Maecenas, who had thrived in the flexible power dynamics of the civil war period, found himself less suited to the emerging imperial bureaucracy. His preference for operating behind the scenes rather than holding official titles became increasingly incompatible with the evolving Augustan regime.

Lasting Contributions to Roman Architecture

Beyond literature, Maecenas left his mark on Rome's physical landscape. His vast estate on the Esquiline Hill pioneered new approaches to urban luxury living. He transformed what had been a necropolis into Rome's first private pleasure gardens—the Horti Maecenatis. These lavish grounds featured promenades, pavilions, and the first heated swimming pool in Rome, setting new standards for aristocratic residences that would influence imperial palace design.

The Architectural Innovator

Maecenas demonstrated particular interest in architectural advancement. His Esquiline complex included an unusual tower-like structure providing panoramic views of Rome—an early example of the Roman penchant for architectural spectacle. He may have also commissioned the Auditorium of Maecenas, a semi-subterranean hall whose purpose remains debated but which showcases sophisticated Roman construction techniques. These projects reflected the same refined aesthetic discernment he applied to literature.

The Death and Legacy of Maecenas

Maecenas died in 8 BCE, leaving behind no children—an unusual circumstance for a Roman aristocrat. In his will, he famously entrusted Augustus with care of "his Horace," showing the depth of personal connection underlying his patronage relationships. While his political role had diminished in his final years, his cultural legacy was already firmly established through the works he had nurtured.

The Posthumous Reputation

Ancient historians offered mixed assessments of Maecenas. Tacitus praised his administrative skills but criticized his luxurious lifestyle, while Seneca focused on perceived flaws in his character and literary taste. However, these critiques pale against the enduring impact of his cultural patronage—the very fact that later writers felt compelled to discuss him at length testifies to his significance.

Maecenas' Model in Later History

The Maecenas archetype—the wealthy, discerning patron who nurtures artistic genius—recurs throughout Western history. From medieval church patronage to Renaissance princes and modern philanthropists, cultural benefactors have looked to Maecenas as their model. The Medici family's support of Florentine artists during the Renaissance consciously emulated Maecenas' example, as did Louis XIV's cultivation of French arts.

From Antiquity to Modernity

The transition from aristocratic patronage to modern systems of arts funding represents one of history's great cultural shifts, yet Maecenas' basic principles remain relevant. Contemporary foundations like the Guggenheim or MacArthur programs adapt his model to modern contexts, proving the durability of his vision for supporting creative excellence.

Philosophical Underpinnings of Maecenas' Patronage

Beneath Maecenas' practical support of artists lay a coherent philosophy about culture's role in society. His approach synthesized several key ideas:

- The belief that great art benefits both creator and society

- Recognition that material security enables creative risk-taking

- Understanding that indirect influence proves more lasting than overt control

- Conviction that cultural achievements define civilizations more than military victories

These principles distinguished his patronage from mere conspicuous consumption or political manipulation.

Literary Depictions Through History

Maecenas' legend grew in later literature, often portrayed as the ideal enlightened patron. Dante places him in Limbo alongside other virtuous pagans in The Divine Comedy. Renaissance humanists frequently invoked his name when seeking patronage for their own work. Modern historical novels and dramas about Augustan Rome typically feature Maecenas as a pivotal supporting character—testament to his enduring dramatic appeal.

The Classical Tradition's Debt

Without Maecenas' intervention, crucial works of Latin literature might never have been written or survived. The Aeneid—a cornerstone of Western literary tradition—exists in significant part due to his support. This single contribution alone secured his place in cultural history, as Virgil's epic became a foundational text for European education until modern times.

Maecenas in Contemporary Scholarship

Modern classical scholarship continues to reassess Maecenas' legacy. Recent studies examine his Etruscan heritage's influence on his aesthetic sensibilities, his role shaping early imperial administration, and the networking aspects of his patronage system. Digitization projects now reconstruct his Esquiline gardens using archaeological data, offering new insights into how physical space supported his cultural activities.

Patronage Studies

The field of patronage studies frequently uses Maecenas as a benchmark for analyzing artistic support systems. Comparative analyses examine how his model differs from later systems like medieval church patronage or modern government arts funding. These studies confirm the remarkable efficiency of his approach—maximum cultural output from relatively modest (by imperial standards) investment.

Conclusion: The Eternal Patron

Twenty centuries after his death, Maecenas endures as the archetypal cultural benefactor. His genius lay in recognizing that supporting art required more than money—it demanded discernment to identify true talent, patience to allow creative development, and wisdom to avoid heavy-handed direction. In Virgil and Horace, he chose artists whose work would transcend their time, ensuring his own legacy by association.

The term "maecenas" remains current in multiple languages because it fills a permanent need—the designation of that rare combination of wealth, taste, and generosity that can elevate a society's cultural achievements. In an age where arts funding faces perpetual challenges, Maecenas' example reminds us that supporting creativity isn't mere charity, but an investment in civilization's future.

From the Augustan Age to our digital era, the story of Maecenas demonstrates how one visionary patron can alter the course of cultural history. His legacy lives not just in museum labels and footnotes, but in the very idea that enlightened patronage can produce works that outlast empires and inspire generations across millennia.

.jpg)

Comments