Livy: The Chronicler of Rome's Grandeur

Introduction: The Life and Times of Titus Livius

Titus Livius, more commonly known as Livy, stands as one of ancient Rome’s most esteemed historians. Born in 59 BCE in Patavium (modern-day Padua, Italy), Livy witnessed the tumultuous transition from the Roman Republic to the Roman Empire under Augustus. His magnum opus, Ab Urbe Condita Libri (Books from the Foundation of the City), is a sprawling historical narrative that chronicles Rome’s origins, its rise to dominance, and its moral and political evolution. Though only a fraction of his original 142 books survive, Livy’s work remains a cornerstone of Roman historiography.

Early Life and Influences

Livy’s birthplace, Patavium, was a prosperous city in northern Italy known for its conservative values and strong republican sympathies. This environment likely influenced Livy’s admiration for Rome’s traditional virtues—virtues that he would later lament as declining in his own time. Unlike many Roman historians who engaged in politics or military service, Livy dedicated himself entirely to scholarship. Moving to Rome around 30 BCE, he found patronage under Emperor Augustus, who admired his literary prowess and moralistic tone.

Augustus’ reign marked a period of cultural revival, often termed the "Golden Age of Latin Literature." Livy’s writing flourished in this atmosphere, alongside contemporaries like Virgil and Horace. However, while Augustus promoted Livy’s work, the historian maintained a nuanced stance on Rome’s political shifts, subtly critiquing autocracy while celebrating Rome’s past glories.

The Scope and Structure of Ab Urbe Condita

Livy’s monumental work, Ab Urbe Condita, ambitiously sought to document Rome’s history from its mythical founding in 753 BCE to the reign of Augustus. Organized into 142 books, only Books 1–10 and 21–45 survive in full, with fragments and summaries (called Periochae) preserving the outlines of the rest. His narrative blended legend, historical fact, and moral lessons, presenting Rome’s past as a series of exempla—models of virtue and vice for readers to emulate or avoid.

The first decade (Books 1–10) covers Rome’s early kings, the establishment of the Republic, and its struggles against neighboring powers. The third decade (Books 21–30) focuses on the Second Punic War, where Livy’s gripping account of Hannibal’s invasion and Rome’s resilience remains legendary. Later books delve into Rome’s expansion across the Mediterranean, internal political strife, and the eventual collapse of republican ideals.

Livy’s Historical Method: Between Myth and Reality

Livy’s approach to history was not purely academic; he prioritized storytelling and moral instruction over strict factual accuracy. He openly acknowledged the challenges of verifying early Roman history, writing, "Events before Rome was born or thought of have come down to us in old tales with more of the charm of poetry than of sound historical record." Despite this, he wove these legends into a coherent narrative, treating them as foundational to Rome’s identity.

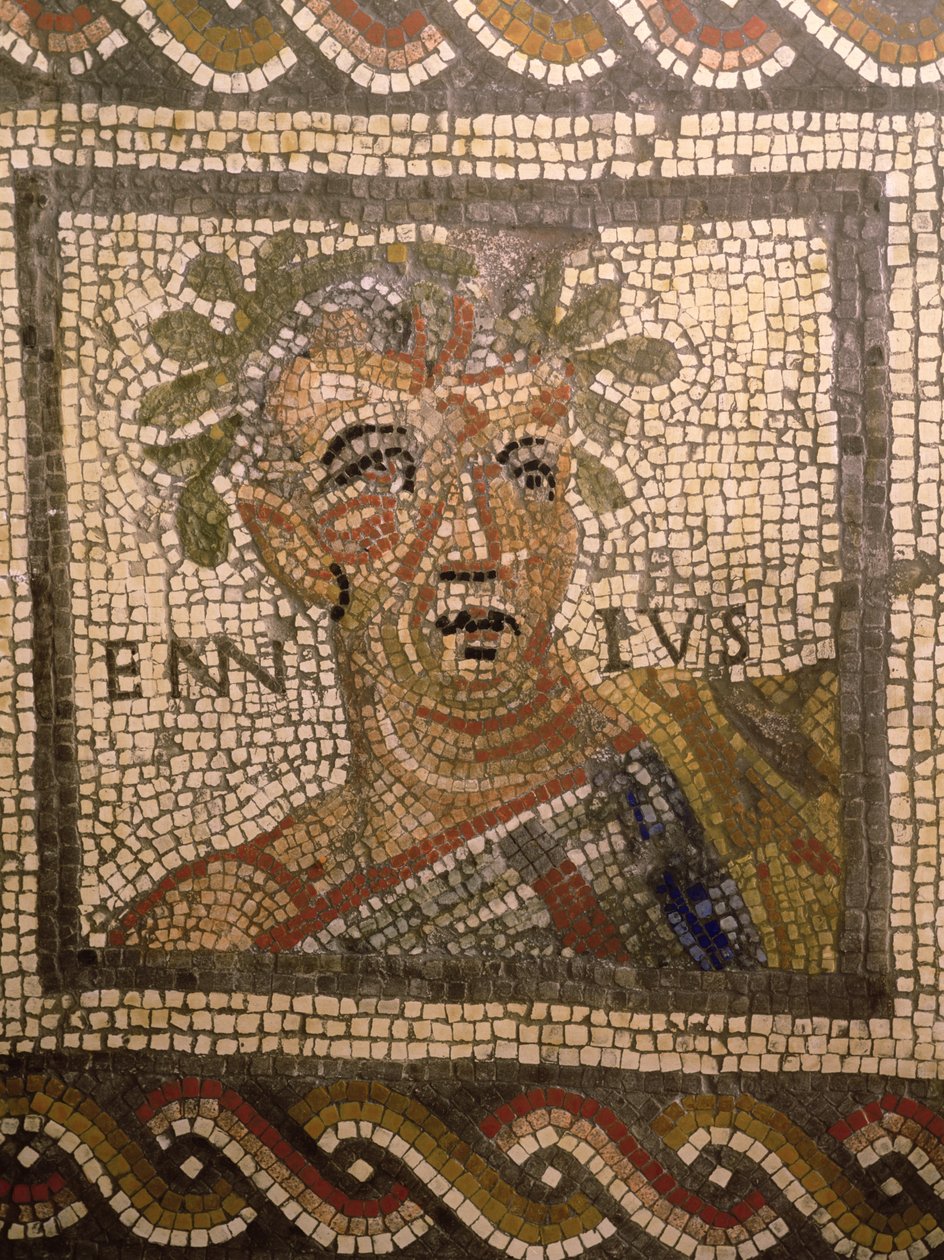

His reliance on earlier sources—such as Fabius Pictor, Polybius, and Annalists—was selective, often favoring dramatic or didactic elements. While modern historians critique Livy for occasional inaccuracies and biases, his work provides invaluable insight into how Romans viewed their heritage. His vivid portrayals of figures like Romulus, Horatius Cocles, and Cincinnatus became iconic, shaping Rome’s self-image for centuries.

Themes and Moral Lessons in Livy’s Work

A central theme in Livy’s history is the interplay of virtue and decline. He idealized Rome’s early days as a time of frugality, piety, and self-sacrifice, contrasting it with the moral decay he perceived in the late Republic. Stories like that of Lucretia—whose rape and suicide symbolized the consequences of tyranny—reinforced the importance of honor and accountability.

Livy also emphasized the role of Fortune (Fortuna) in shaping Rome’s destiny. While Rome’s greatness seemed preordained, its survival depended on the virtues of its leaders and citizens. His account of the Second Punic War, for instance, highlights both Hannibal’s brilliance and Rome’s tenacity, ultimately attributing victory to Roman resilience and divine favor.

Livy’s Legacy and Influence

Though Livy’s work was incomplete even in antiquity, his impact endured. Later Roman historians, including Tacitus, drew inspiration from his style and themes. During the Renaissance, scholars like Petrarch and Machiavelli revisited Livy’s texts, extracting political and ethical lessons for their own eras. His narratives of republican glory even influenced the founders of modern democracies, including the framers of the United States Constitution.

Today, Livy is celebrated not merely as a historian but as a master storyteller who shaped Rome’s mythology and moral imagination. His blending of fact and legend invites readers to ponder how nations construct their identities through history—a question as relevant now as it was in Augustus’ Rome.

In the next section, we will delve deeper into Livy’s depiction of key historical events, examining how his literary techniques brought Rome’s past to life while advancing his moral and political vision.

Livy’s Depiction of Rome’s Defining Moments

Livy’s Ab Urbe Condita is particularly renowned for its vivid portrayal of pivotal events in Roman history. By blending historical records with rhetorical flair, he transformed dry chronicles into gripping narratives, ensuring that readers not only learned about Rome’s past but also felt its drama and moral weight. One striking example is his account of the foundation of Rome, intertwined with the legendary tale of Romulus and Remus. Livy presents the brothers’ struggle not merely as a power dispute but as a foundational moral lesson—emphasizing destiny versus ambition, unity versus discord—which would echo throughout Rome’s history.

The Early Republic: Heroism and Civic Virtue

A defining characteristic of Livy’s early books is his celebration of republican heroes whose virtues exemplified Rome's idealized past. One such figure was Lucius Junius Brutus, who expelled the last Roman king, Tarquin the Proud, and established the Republic. Livy immortalizes Brutus not just as a liberator but as a tragic figure who condemned his own sons to death for conspiring to restore the monarchy—a poignant illustration of duty over personal affection.

Similarly, his account of Horatius Cocles, the lone warrior who defended Rome’s bridge against the Etruscan army, became emblematic of patriotic sacrifice. Livy’s embellishments—such as Horatius’ dramatic plunge into the Tiber—served to elevate individual bravery into a national mythos. These tales were less about factual precision than about shaping collective memory, reinforcing ideals like virtus (courage) and pietas (duty).

The Second Punic War: Livy’s Masterpiece of Suspense

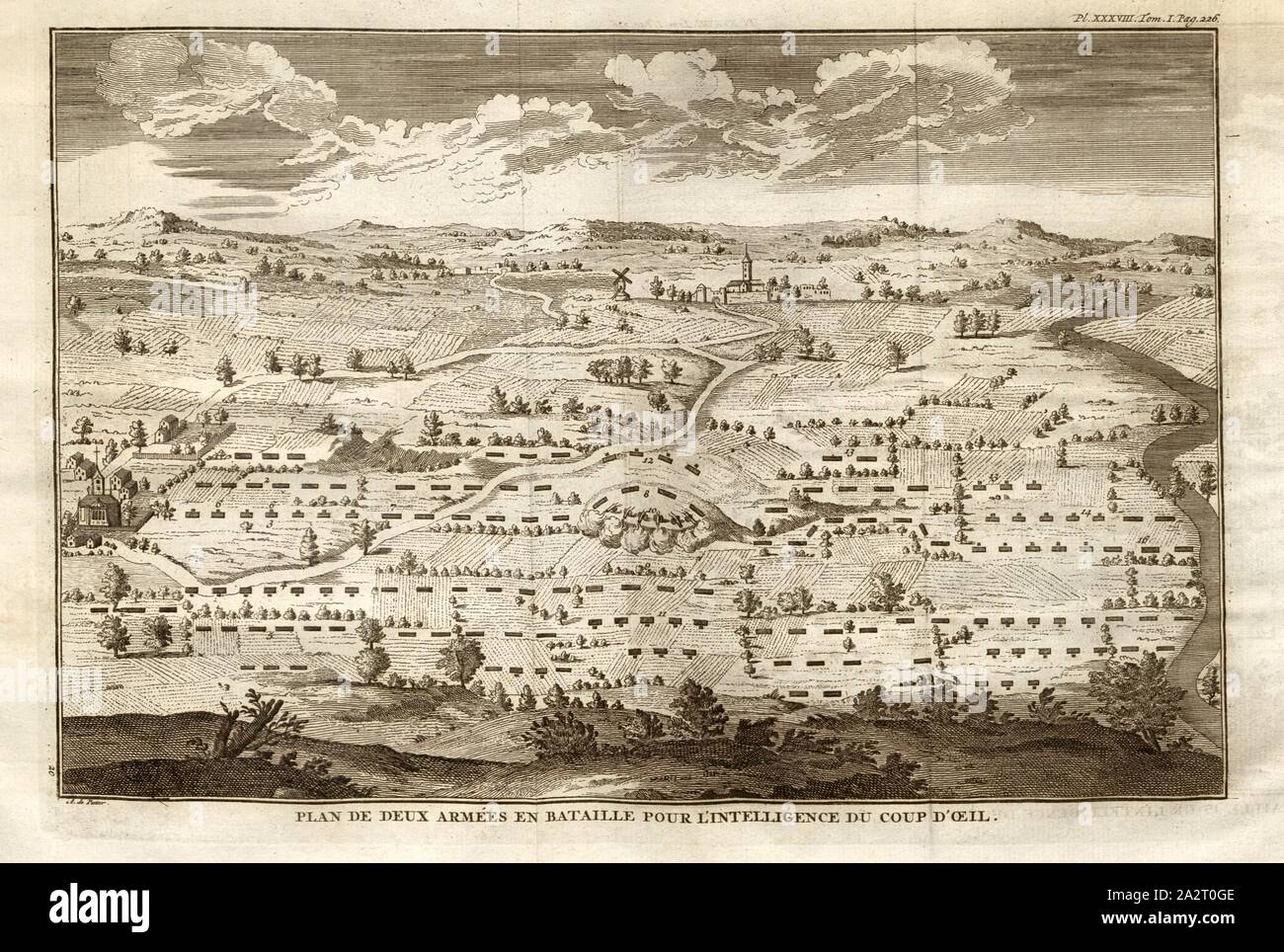

Among Livy’s most compelling narratives is his treatment of the Second Punic War (218–201 BCE), particularly Hannibal’s audacious crossing of the Alps and his near-destruction of Rome. Livy’s portrayal of Hannibal is remarkably nuanced; he admires the Carthaginian general’s genius yet underscores his flaws—excessive pride and cruelty—which ultimately thwarted his victories. The climactic Battle of Cannae (216 BCE), where Hannibal annihilated a numerically superior Roman force, is recounted with chilling detail, emphasizing both the horror of defeat and the resilience that followed.

Yet Livy’s true focus is Rome’s response to disaster. He meticulously documents how the Republic, even in its darkest hour, refused to negotiate peace, embodying the unwavering spirit of Senatus Populusque Romanus (SPQR). Scipio Africanus’ eventual triumph at Zama is framed as inevitable—not just due to military skill but because of Rome’s moral superiority. This dichotomy between Hannibal’s brilliance and Rome’s endurance allowed Livy to explore deeper themes of fate, perseverance, and divine justice.

Livy as a Literary Craftsman

Beyond his role as a historian, Livy was a master of rhetoric and narrative technique. His prose combined the grandeur of epic poetry with the precision of classical historiography. Unlike Thucydides, who prioritized factual rigor, or Tacitus, whose writing dripped with irony, Livy sought to inspire and moralize. For instance, he frequently employed direct speeches—fictional yet plausible dialogues—to reveal character motivations and heighten drama. The speech he attributes to Hannibal before Cannae, rallying his troops with reminders of past victories, is a literary invention but serves to humanize the enemy and deepen the narrative’s tension.

Livy also excelled in pacing and symbolism. In Book 1, the rape of Lucretia by Tarquin’s son is not just a crime but a catalyst for revolution, symbolizing the tyranny of kingship. Similarly, the tale of Cincinnatus—the farmer-dictator who saved Rome and willingly returned to his plow—is structured to contrast republican simplicity with later decadence. These stories functioned as moral parables, reinforcing Livy’s belief that history’s purpose was to teach virtue.

Criticism and Historical Reliability

Livy’s methods have faced scrutiny, especially from modern historians who prioritize empirical evidence. His reliance on earlier annalists, many of whom wrote centuries after the events they described, introduced errors and inconsistencies. For example, his description of early Rome’s population size or military numbers often defies plausibility. Moreover, his patriotic bias led him to downplay Roman defeats or attribute them to moral failings rather than strategic blunders.

Yet these "flaws" also reveal Livy’s intent: he was less a scientific chronicler than a national storyteller. His histories were meant to unify Romans under a shared heritage, especially during Augustus’ cultural reforms. By emphasizing cyclical patterns of rise and decline, Livy subtly warned that without a return to traditional values, Rome risked repeating the chaos of the late Republic.

Livy’s Reception in Antiquity and Beyond

In his own time, Livy was hailed as a literary giant. The elder Pliny reportedly traveled to Rome just to hear him recite passages. Emperor Claudius was so influenced by Livy that he attempted to revive archaic Latin terms in official documents. However, as the Western Roman Empire collapsed, much of Ab Urbe Condita was lost—likely due to the sheer cost and effort of copying such a vast work during turbulent times.

The Renaissance revived interest in Livy, with humanists like Petrarch and Leonardo Bruni poring over his surviving texts. Niccolò Machiavelli’s Discourses on Livy (1531) treated his histories as a blueprint for governance, extracting lessons on republicanism, military strategy, and civic duty. Centuries later, America’s Founding Fathers, particularly John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, studied Livy to understand the dangers of tyranny and the virtues of balanced government.

Conclusion of Part Two: The Moral Historian

Livy’s genius lay in his ability to merge history with moral philosophy, creating a work that transcended its era. While scholars debate his accuracy, his narratives endure precisely because they capture universal truths about power, resilience, and human nature. His Rome—part historical reality, part aspirational ideal—continues to fascinate as both a cautionary tale and an inspiration.

In the final section, we will examine Livy’s philosophical outlook, his subtle critiques of Augustus’ regime, and his enduring legacy in literature and political thought.

Livy’s Philosophy: Between Republican Ideals and Imperial Reality

The tension between Livy's republican sympathies and his position within Augustus' Rome represents one of the most fascinating aspects of his work. While he enjoyed imperial patronage, his histories reveal a nuanced understanding of power that neither fully endorsed nor openly opposed the Principate. This subtle balancing act allowed him to celebrate Rome's past while commenting indirectly on its present.

The Shadow of Augustus

Livy began writing Ab Urbe Condita around 27 BCE, just as Augustus was consolidating power. Though he dedicated parts of his work to the emperor, scholars have long debated whether this reflected genuine admiration or political necessity. His portrayal of early republican heroes like Cincinnatus, who relinquished absolute power voluntarily, can be read as implicit commentary on contemporary politics.

Particularly telling is Livy's treatment of kingship throughout his narrative. His accounts of Rome's seven kings alternate between depicting some as benevolent leaders and others as tyrants, creating a thematic tension that reflected anxieties about concentrated power under Augustus. The story of the rape of Lucretia and the overthrow of the monarchy carried particular resonance during a time when Rome was transitioning from republic to empire.

Livy's Psychological Insight

What sets Livy apart from many ancient historians is his remarkable psychological depth. He didn't merely recount events; he explored the motivations, doubts, and inner conflicts of historical figures. His portrayal of Hannibal's march across the Alps, for instance, goes beyond military tactics to examine the Carthaginian general's complex character - his brilliance, his hubris, and his growing desperation.

This psychological approach is particularly evident in Livy's treatment of Roman women. Unlike many ancient historians who marginalized female figures, Livy gave prominent roles to women like Veturia (mother of Coriolanus) and the Sabine women, using them to explore themes of reconciliation, patriotism, and the intersection of private and public life.

The Concept of Roman Destiny

Central to Livy's worldview was the idea of Rome's manifest destiny (fata Romana). However, his conception differed significantly from later imperial propaganda. For Livy, Rome's greatness wasn't guaranteed by divine favor alone, but had to be continually earned through moral rectitude and adherence to traditional values.

This becomes clear in his treatment of pivotal moments like the aftermath of Cannae. Where a simplistic account might focus solely on military recovery, Livy emphasizes Rome's moral resilience - how the Senate rejected ransom offers for Roman prisoners, demonstrating that principles outweighed pragmatism. Such passages reveal Livy's belief that Rome's success depended on maintaining its collective character.

Livy's Influence on Western Thought

The reception of Livy's work has undergone remarkable transformations across different historical periods, reflecting changing attitudes toward history, republicanism, and national identity.

Medieval Rediscovery

During the Middle Ages, Livy was primarily known through epitomes and fragments. The complete surviving portions of his work were gradually rediscovered during the Renaissance, creating scholarly excitement comparable to the recovery of Greek classics. Petrarch's enthusiasm for Livy helped spark the humanist movement, with scholars scouring European monasteries for lost Livian manuscripts.

Machiavelli's Revolutionary Reading

The most consequential interpretation of Livy came from Niccolò Machiavelli, whose Discourses on Livy (1517) fundamentally reinterpreted the ancient historian's work. Where Livy saw moral examples, Machiavelli found political theory. His radical reading transformed Livy from a moralist into a strategist, extracting lessons about statecraft that would influence political thought for centuries.

Machiavelli's analysis particularly focused on Livy's accounts of constitutional crises, arguing they revealed deeper truths about power dynamics that transcended their historical context. This interpretation, while controversial, ensured Livy remained relevant in early modern political discourse.

Enlightenment and Revolutionary Reception

During the 18th century, Livy's work took on new significance for republican movements. The American Founding Fathers, particularly John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, frequently referenced Livy in their correspondence. The Federalist Papers contain numerous Livian allusions, using Roman history as a cautionary tale about the fragility of republican government.

In revolutionary France, Livy became equally important, though interpretations varied dramatically. Conservative classicists emphasized his themes of order and tradition, while radicals highlighted his accounts of popular resistance to tyranny.

The Modern Legacy

Today, Livy's influence extends far beyond classical studies. His narrative techniques have influenced historical writing and journalism, particularly his use of vivid details to bring events to life. The modern concept of "narrative history" owes much to Livy's approach.

Literary Adaptations

Livy's dramatic episodes have inspired countless adaptations, from Renaissance plays to modern novels and films. The story of Horatius at the bridge became a favorite subject for 18th-century painters, while the tragic tale of Lucretia has been reinterpreted in operas, poems, and psychological dramas.

Livy in Contemporary Historiography

Modern historians approach Livy with a dual perspective: appreciating his literary genius while acknowledging his limitations as a source. Archaeological discoveries have sometimes contradicted his accounts, yet his work remains invaluable for understanding Roman self-perception. Recent scholarship has focused particularly on:

- The construction of national identity in Livy's narrative

- Gender representation in his historical accounts

- The interplay between folklore and historical fact

- His influence on later nationalist historiographies

Conclusion: The Enduring Voice of Rome

Livy's true legacy lies not in the factual accuracy of his accounts, but in his profound understanding of how societies remember and interpret their past. Through his blending of myth and history, he created a national narrative that shaped Roman identity for centuries and continues to influence how we think about history's purpose.

His work stands as a monument to the power of storytelling - not just as entertainment, but as a means of preserving values, analyzing power, and understanding human nature. In an age when the study of humanities is often questioned, Livy's enduring relevance reminds us that the stories we tell about our past fundamentally shape our present and future.

More than two millennia after he wrote, Livy's voice still resonates - not merely as a chronicler of ancient Rome, but as one of the most profound explorers of what history means and why it matters.

/image%2F0994950%2F20231227%2Fob_6ee823_oip-le9zan7rfdbd9et6yb3f1whaet-w-246-h.7)

Comments