Gaius Flaminius: The Controversial Tribune and General of Republican Rome

Introduction: A Polarizing Figure in Roman History

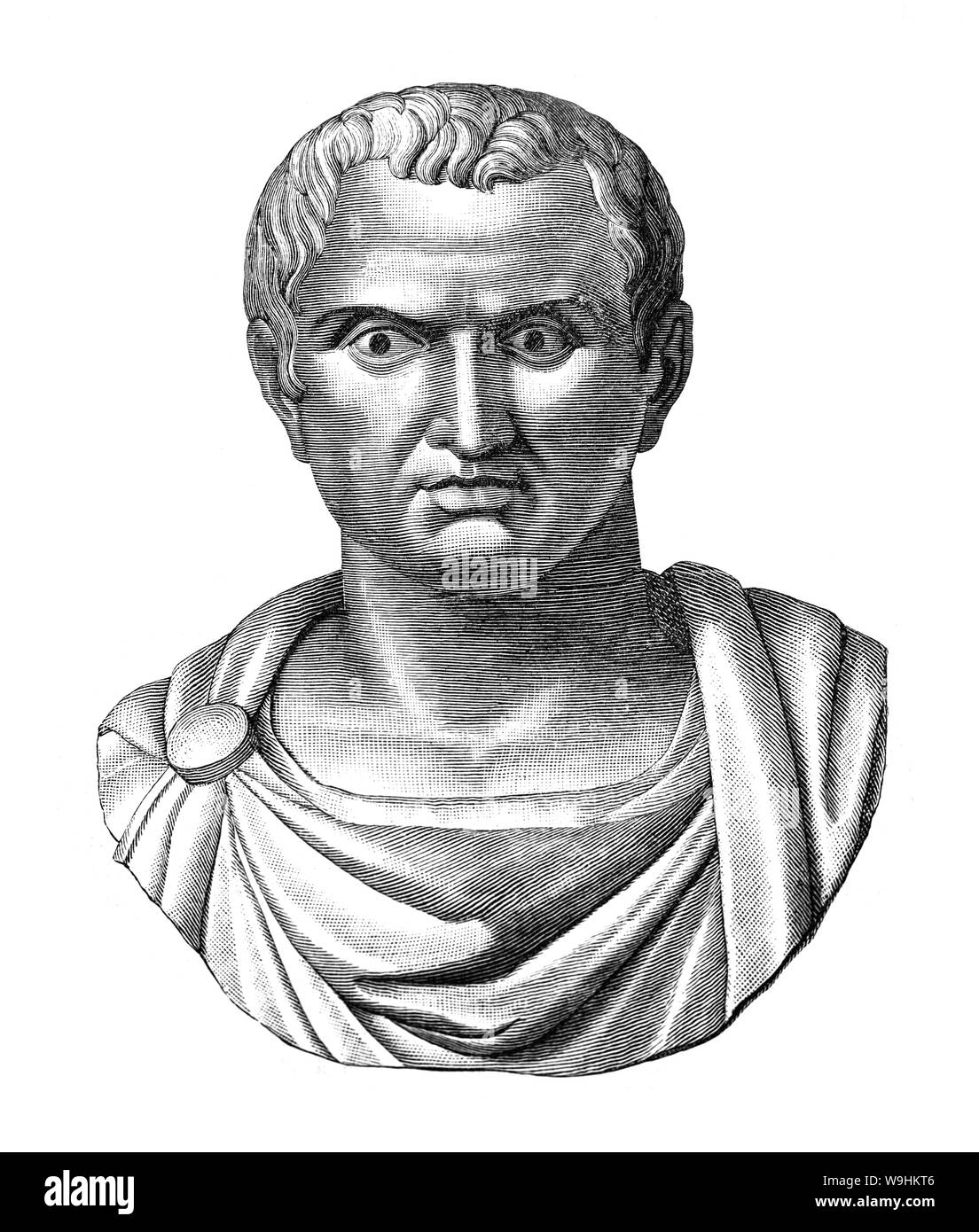

Gaius Flaminius remains one of the most intriguing and debated figures of the Roman Republic. A man of populist leanings and bold reforms, he challenged the conservative aristocracy while serving as both tribune and consul. His controversial policies and eventual demise at the Battle of Lake Trasimene during the Second Punic War secured his place in history as a figure of both admiration and criticism.

Early Life and Political Beginnings

Little is known about Gaius Flaminius’s early life, but historical records place him as a rising political force by the late 3rd century BCE. Hailing from a plebeian family, he emerged as a champion of the common people, distinguishing himself from the elite patrician class that had traditionally dominated Roman politics. His career began with his election as tribune of the plebs in 232 BCE, where he would introduce one of his most contentious reforms.

The Flaminian Land Law: A Populist Gamble

As tribune, Flaminius proposed and passed a law distributing conquered Gallic lands (Ager Gallicus) to Roman citizens, particularly landless plebeians. This move, known as the Lex Flaminia de Agro Gallico, provoked fierce opposition from the Senate. The aristocracy viewed it as a dangerous precedent that undermined their control over public land (ager publicus) and challenged their economic dominance. Despite their resistance, Flaminius pushed the law through, solidifying his reputation as a populist leader.

Rising Through the Cursus Honorum

Flaminius’s career continued to ascend despite—or perhaps because of—his defiance of the senatorial elite. He served as praetor in 227 BCE, overseeing the newly established province of Sicily, and later became consul for the first time in 223 BCE. His consulship would be marked by further controversy, particularly concerning his military command against the Insubres, a Gaulish tribe.

The Consulship and Conflict with the Senate

During his first consulship, Flaminius led a campaign against the Insubres in northern Italy. His aggressive tactics, including crossing the Po River against senatorial advice, led to initial success. However, his opponents in Rome later tried to revoke his command, accusing him of acting without proper consultation. The Senate even dispatched letters attempting to recall him, but legend claims Flaminius ignored them, claiming he would open them only after victory. His triumph over the Insubres earned him a celebration in Rome, though the Senate denied him a full triumph, granting instead an ovation—a lesser honor.

Censorship and the Via Flaminia

In 220 BCE, Flaminius was elected censor, a prestigious position with significant influence over public morals and infrastructure. His most lasting contribution in this role was the construction of the Via Flaminia, a major Roman road stretching from Rome to Ariminum (modern Rimini). This highway facilitated trade and military movement, integrating northern Italy more closely with the heart of the Republic. The road also served as a symbol of his commitment to public works that benefited the broader population.

Political Opposition and Second Consulship

Flaminius’s populist policies and disregard for senatorial tradition made him a polarizing figure. The aristocracy viewed him as a demagogue who threatened the established order, while the plebeians saw him as a defender of their interests. By 217 BCE, the Second Punic War was in full swing, and Rome faced the existential threat of Hannibal’s invasion. Despite—or perhaps because of—his contentious reputation, Flaminius was elected consul for a second time, alongside Gnaeus Servilius.

The Fateful Campaign Against Hannibal

Flaminius’s second consulship would be defined by disaster. Tasked with confronting Hannibal, he took command of the Roman forces in central Italy. Unlike his colleague Servilius, who was stationed farther north, Flaminius acted independently and pursued an aggressive strategy against the Carthaginian general. His decisions, including refusing to wait for reinforcements, have been heavily criticized by ancient historians like Livy and Polybius, who painted him as reckless.

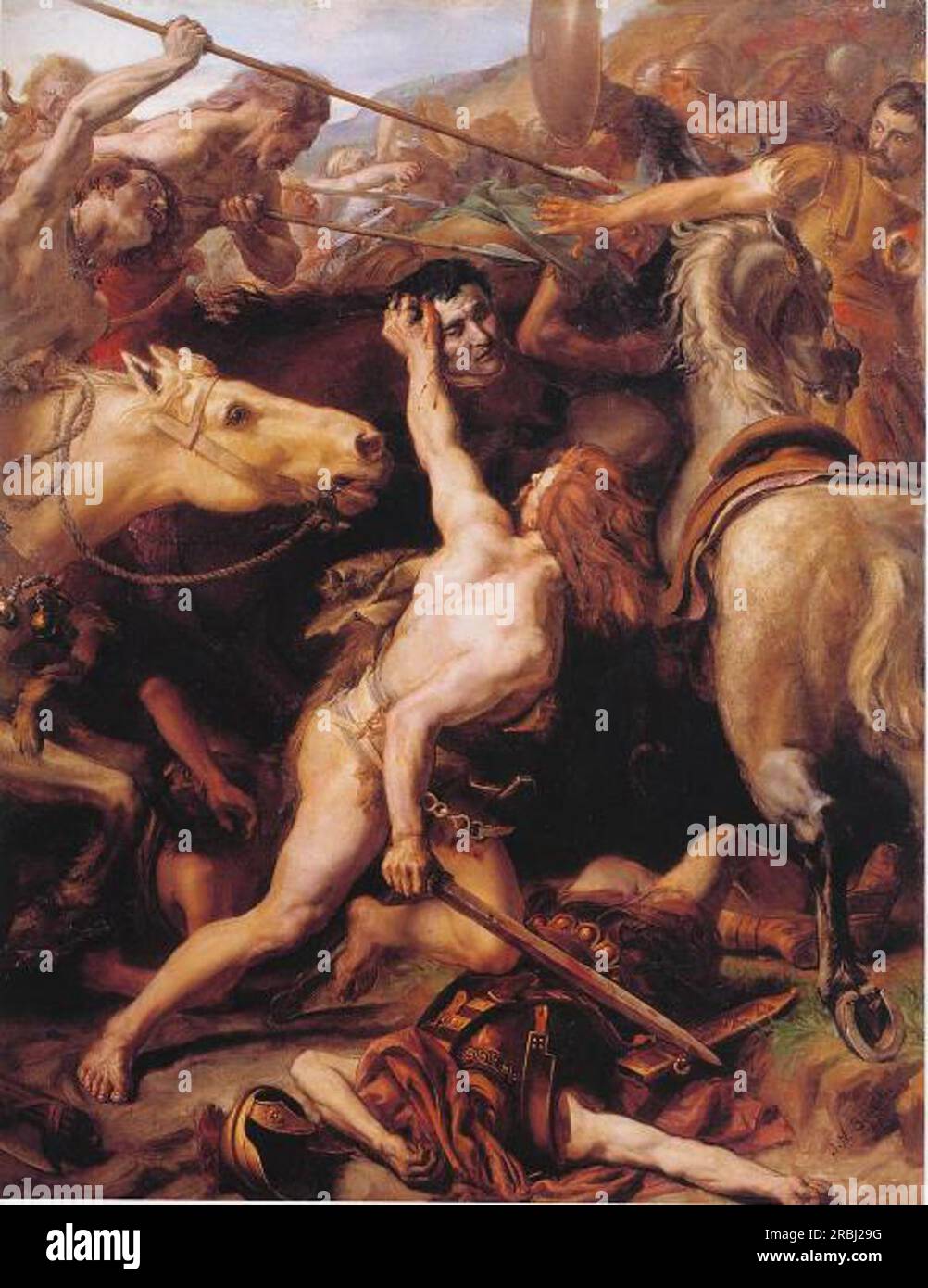

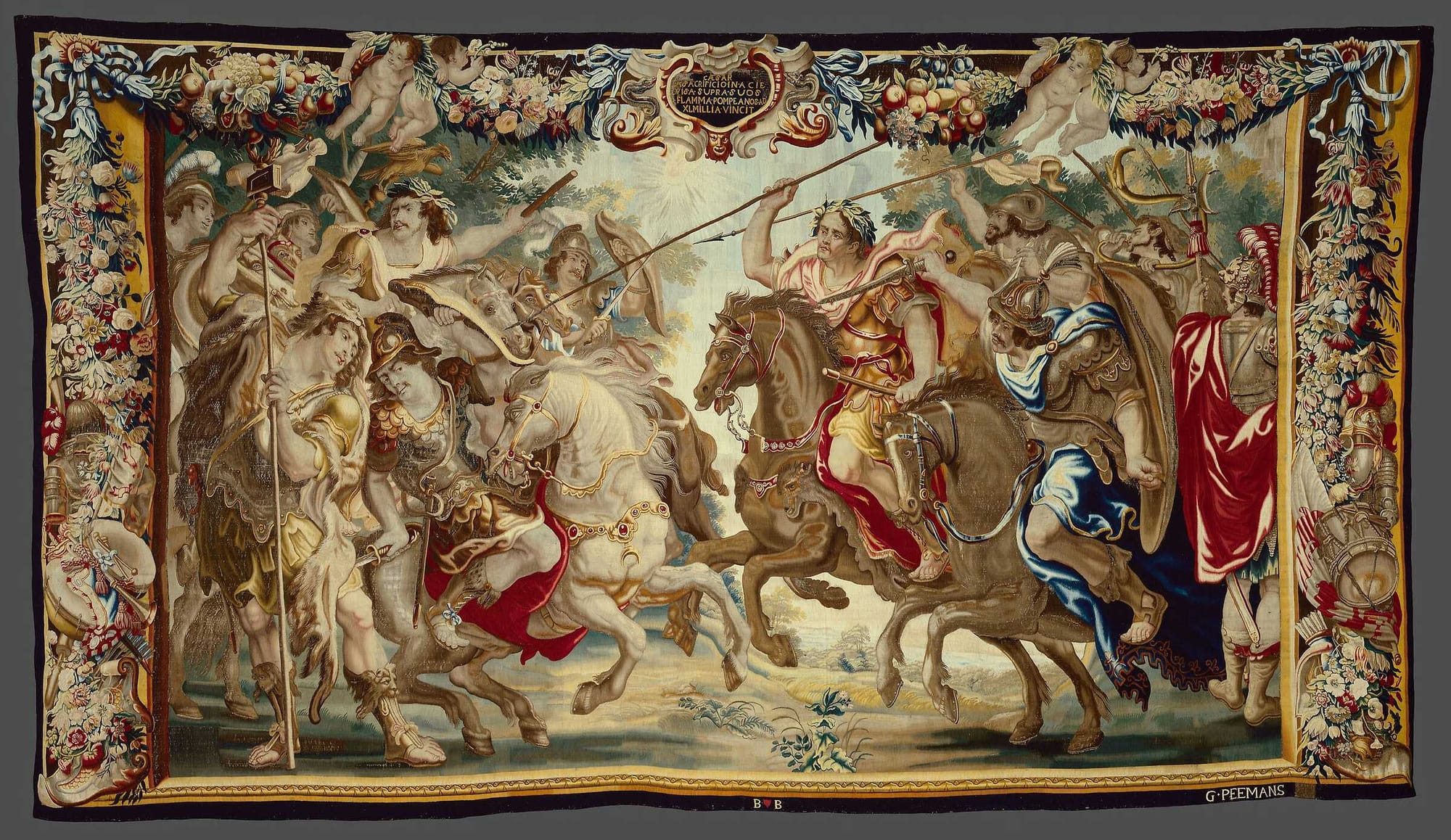

The Ambush at Lake Trasimene

In June 217 BCE, Hannibal lured Flaminius into a trap at Lake Trasimene. The Roman army marched into a narrow pass along the lake’s shore, where Carthaginian forces lay hidden in the hills. As the fog lifted, Hannibal’s troops ambushed Flaminius’s legions, cutting off escape routes. The battle was a massacre. Thousands of Romans, including Flaminius himself, perished. His death and the annihilation of his army sent shockwaves through Rome, marking one of the worst defeats in Republican history.

Legacy and Historical Interpretation

Gaius Flaminius’s legacy remains fiercely debated. Ancient historians, often writing from an aristocratic perspective, condemned him for his populism and alleged hubris. Modern scholars, however, offer a more nuanced view. While acknowledging his strategic missteps, many recognize his contributions to Roman infrastructure and his challenge to a stagnant political elite. His career underscores the tensions between plebeian and patrician interests in the evolving Republic.

Conclusion of Part One: A Prelude to Rome’s Greatest Crisis

Flaminius’s life and death set the stage for one of Rome’s darkest hours. His defeat at Lake Trasimene left the Republic vulnerable, forcing it to turn to emergency measures and new leaders, including Quintus Fabius Maximus. In the next section, we will explore the broader implications of Flaminius’s policies, the aftermath of his defeat, and how his legacy influenced the trajectory of the Second Punic War and Roman political development.

The Aftermath of Lake Trasimene: Rome in Crisis

The catastrophic defeat at Lake Trasimene sent Rome into a state of panic. News of Flaminius’s death and the destruction of an entire consular army reached the city, igniting fears that Hannibal might march on Rome itself. The Senate swiftly declared a state of emergency (justitium), suspending normal government functions. In an unprecedented move, the Romans appointed Quintus Fabius Maximus as dictator, tasking him with the defense of the Republic. Fabius’s strategy of avoiding direct confrontation—later dubbed the "Fabian strategy"—stood in stark contrast to Flaminius’s aggressive approach, highlighting the deep divide in Roman military thinking.

The Political Fallout and Scapegoating of Flaminius

In the wake of the disaster, Flaminius’s reputation suffered immense damage. Senatorial historians, particularly those aligned with the aristocracy, placed the blame squarely on his shoulders. They accused him of neglecting religious omens, ignoring military precautions, and allowing his personal ambition to cloud his judgment. Livy’s account, written centuries later, famously depicted Flaminius as arrogant and impious, claiming he disregarded unfavorable auspices before battle. Modern historians, however, question the reliability of these narratives, suggesting they reflect political grudges rather than objective facts.

Religious Condemnation and the Sibylline Books

The Roman elite weaponized religious tradition to discredit Flaminius further. Consulting the Sibylline Books—Rome’s sacred prophetic texts—the Senate claimed that the defeat was divine punishment for Flaminius’s disregard of religious rites. This narrative reinforced the idea that his populist policies had angered the gods. A series of expiatory rituals were performed, including the controversial sacrifice of a Gallic and Greek couple in the Forum Boarium, intended to appease the deities. Whether these rites were genuine attempts to atone or political theater remains debated.

Flaminius’s Policies Revisited: Progress Versus Provocation

Despite his vilification, Flaminius’s policies had long-term impacts that shaped Rome’s socio-political landscape. The distribution of land under the Lex Flaminia alleviated urban poverty and strengthened the Roman peasantry, which formed the backbone of the Republic’s military. Meanwhile, the Via Flaminia became a vital artery for commerce and troop movements, contributing to Rome’s economic and territorial expansion. His censorship also saw the construction of the Circus Flaminius, a public venue that enhanced civic life in Rome. These achievements complicate the one-dimensional portrayal of Flaminius as a reckless demagogue.

Contrasting Leadership: Flaminius vs. Fabius Maximus

The divergent strategies of Flaminius and Fabius Maximus underscored a fundamental tension in Roman military doctrine. Where Flaminius favored decisive action, Fabius advocated patience and attrition. While Fabius’s tactics earned him the epithet "Cunctator" (the Delayer), they also faced criticism for perceived cowardice. The contrast between the two men became a recurring theme in Roman historiography, framing broader debates about risk-taking versus caution in warfare. Over time, Rome would synthesize both approaches, adopting flexibility as a hallmark of its military success.

Hannibal’s Psychological Warfare and Flaminius’s Role

Flaminius’s death served Hannibal’s broader strategy of psychological domination. By eliminating both consular armies (Flaminius’s at Trasimene and Servilius’s shortly after), Hannibal demonstrably proved Rome’s vulnerability. He deliberately spared non-Roman Italian allies captured in battle, releasing them to spread fear and undermine Roman hegemony. This tactic exploited the political fractures Flaminius himself had highlighted—divisions between Rome and its allies, and between the Senate and the plebeians. In this light, Flaminius’s downfall was not merely a tactical blunder but a symptom of structural weaknesses in the Republic.

Economic Reforms and Agrarian Tensions

Flaminius’s agrarian policies had far-reaching economic implications. By allocating land to landless citizens, he sought to halt the decline of the smallholding farmer class—a group critical to Rome’s militia-based army. However, this redistribution threatened the lucrative rents that wealthy senators earned from ager publicus. The backlash against Flaminius foreshadowed later conflicts, notably the Gracchan reforms a century later, which faced even bloodier resistance from the aristocracy. His career thus marks an early chapter in Rome’s struggle over land reform and economic inequality.

Military Tactics: Was Flaminius Truly Incompetent?

While ancient sources paint Flaminius as inept, a reassessment suggests his strategy was not without merit. Prior to Trasimene, he successfully campaigned against the Gauls. At Lake Trasimene, his decision to engage Hannibal may have been influenced by the need to protect allied territories from devastation—a political necessity as much as a military gamble. The ambush succeeded partly due to terrain and Hannibal’s brilliance, not solely Flaminius’s errors. Critics also overlook that other Roman generals, including the revered Scipio Africanus, later adopted aggressive tactics against Hannibal with success.

The Cultural Legacy: Flaminius in Literature and Ideology

Beyond politics and war, Flaminius became a symbol in Roman cultural memory. Conservative writers like Cicero used his story to warn against popularis (populist) leaders. Conversely, reformers invoked his name to justify challenging senatorial authority. Renaissance and Enlightenment thinkers, fascinated by republicanism, debated his legacy anew. Niccolò Machiavelli referenced him in "Discourses on Livy," analyzing the perils of ignoring public opinion—a nuanced critique that transcended ancient prejudices.

Archaeology and the Via Flaminia Today

Modern archaeology validates Flaminius’s infrastructural vision. Sections of the Via Flaminia, now incorporated into Italian highways like the SS3, remain in use. Excavations reveal milestones bearing his name and the sophisticated engineering of bridges and tunnels. These physical remnants counterbalance the literary vilification, attesting to his practical governance. Tourist paths along the ancient route, dubbed the "Cammino dei Sette Acquedotti," attract history enthusiasts retracing the road Flaminius built.

Conclusion of Part Two: A Legacy Re-examined

Flaminius’s story is a mosaic of ambition, reform, and tragedy. His defeat became a cautionary tale, yet his contributions endured in Rome’s roads, laws, and political discourse. The final section will explore how later generations weaponized or rehabilitated his memory, the lessons drawn from his clash with Hannibal, and his place in the pantheon of Republican leaders who shaped Rome’s destiny.

Flaminius in the Annals of Roman Political Thought

The figure of Gaius Flaminius became a touchstone in Rome's political discourse for centuries after his death. Republican-era thinkers repeatedly invoked his career when debating the limits of popular power and senatorial authority. Cicero, while wary of demagogues, acknowledged Flaminius's genuine concern for the plebs in his treatise *De Officiis*. Meanwhile, radical reformers like Gaius Gracchus deliberately echoed Flaminius's rhetoric when proposing their own agrarian laws. This ideological battle ensured Flaminius remained relevant long after the Punic Wars ended—an enduring symbol of class conflict in Roman constitutional debates.

The Fabian Myth and Flaminius's Rehabilitation

As Rome's confrontation with Hannibal continued, the Senate's preferred narrative increasingly contrasted Fabius Maximus's caution with Flaminius's recklessness. Yet cracks in this dichotomy appeared even in antiquity. Historians noted that Fabius's strategy of delay couldn't win the war—only Scipio Africanus's aggression ultimately defeated Carthage. By the late Republic, some thinkers argued Flaminius had been partly vindicated: Rome needed both prudent defense and bold offense. The poet Ennius captured this balanced view in his verse: *"Unus homo nobis cunctando restituit rem... non ponebat enim rumores ante salutem"* (One man by delaying restored the state... yet one cannot always put safety before action).

Military Reforms Inspired by Disaster

The tactical lessons of Lake Trasimene directly influenced Rome's military evolution. Recognizing how Hannibal exploited traditional manipular formations, Rome began experimenting with more flexible cohort structures. The disaster also prompted changes in command protocols—consuls were discouraged from operating independently without coordination, a criticism often levied against Flaminius. Most significantly, the Republic developed the concept of *provocatio* (right of appeal) for soldiers, giving them legal protections against commanders' rash decisions—a reform some scholars link to popular outrage over Flaminius's perceived waste of lives.

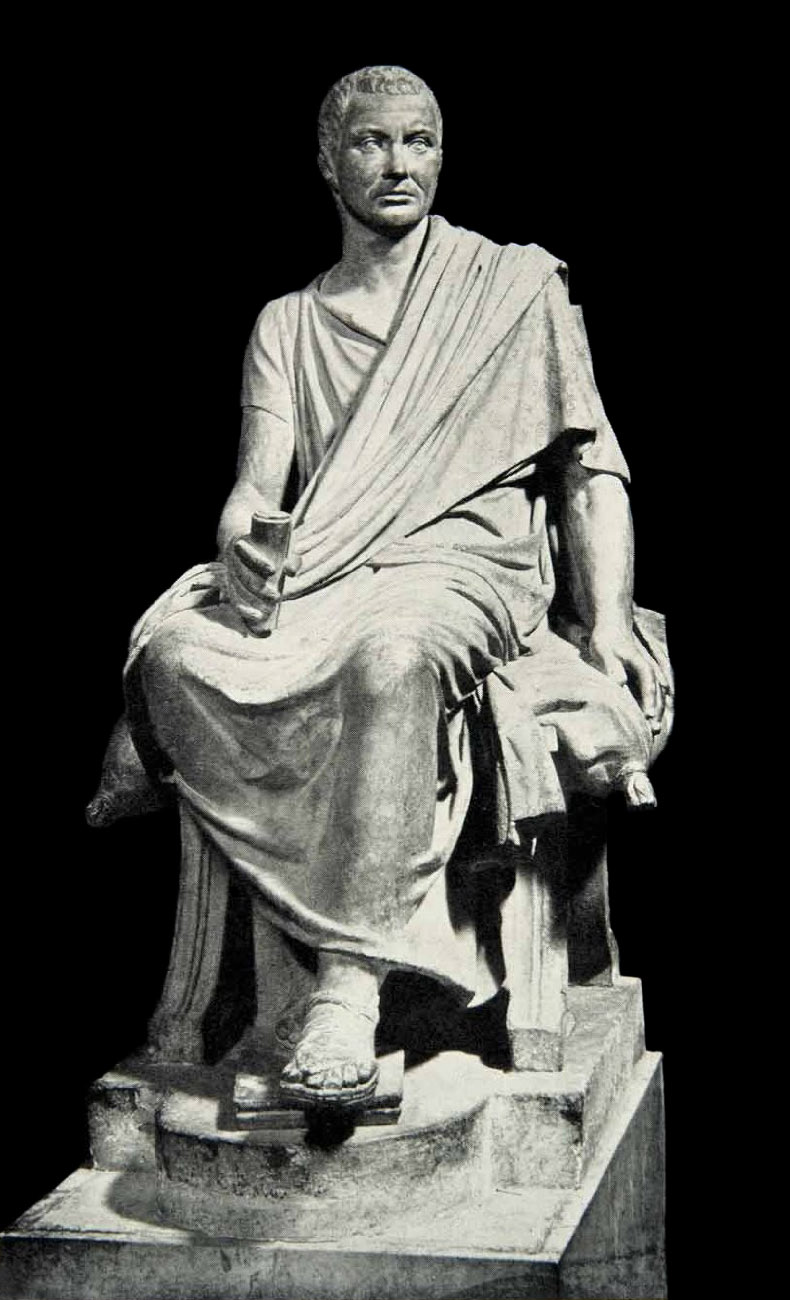

Flaminian Traditions in the Imperial Era

Under Augustus, Flaminius's legacy underwent symbolic rehabilitation. The first emperor recognized the propaganda value of associating his reign with popular builders rather than aristocratic warriors. Augustus restored the Circus Flaminius and expanded the Via Flaminia northward to Ravenna, deliberately acknowledging its founder. Later emperors like Trajan would follow this model, using Flaminius's infrastructure as prototypes for their own vast construction programs. The road became so iconic that Roman itineraries measured distances *"a Milliario Aureo ad Flaminiam"* (from the Golden Milestone to the Flaminian Way).

Christianization and the Via Flaminia's New Purpose

With Christianity's rise, the route Flaminius built took on spiritual significance. Pilgrims traveling to Rome from the Adriatic coast followed his highway, which became dotted with churches and waystations. The martyrdom of St. Felix along the Via Flaminia in 303 CE further sanctified the road. Remarkably, this Christian adoption inverted the road's original martial purpose—where legions once marched to conquest, now penitents walked toward salvation. The Basilica of San Silvestro near the original Flaminian Gate stands as testimony to this transformation.

Medieval Reinterpretations and Dante's Allegory

Medieval chroniclers recast Flaminius as a tragic exemplar of pride. Dante Alighieri immortalized this view in *Divine Comedy*'s *Inferno*, where Flaminius appears among those damned for warmongering—a striking departure from classical portrayals. Contrastingly, republican city-states like Florence celebrated him as an early opponent of tyranny. This dual interpretation reflected medieval Italy's political fractures, with Guelphs and Ghibellines selectively invoking Roman history to justify their factions.

Enlightenment Reassessment

18th-century historians brought new scrutiny to Flaminius's story. Edward Gibbon, while critical of his military failure, praised his land reforms as proto-democratic in *The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire*. French revolutionaries later adopted this view, with Mirabeau citing Flaminius as a model for breaking aristocratic privilege. Simultaneously, military theorists like Clausewitz analyzed Lake Trasimene as a textbook case of terrain-based ambush—shifting focus from Flaminius's character to universal tactical principles.

Modern Historiography: Beyond Hero or Villain

Contemporary scholarship dismantles simplistic judgments of Flaminius. Archaeological evidence proves his infrastructure projects stabilized Italy's economy for generations. Demographic studies suggest his land distribution helped maintain Rome's military manpower pool despite horrific Punic War losses. New readings of Polybius reveal likely senatorial bias in accounts of divine omens—no contemporary records mention Flaminius ignoring sacrifices. Revisionist historians now posit that had he survived Trasimene, his career might have been remembered like Marius's: controversial but transformative.

The Flaminius Paradox: Populism and Patriotism

Flaminius embodies a central paradox of republican governance. His defiance of senatorial norms alienated elites, yet his policies strengthened Rome's long-term resilience. Modern parallels abound; leaders who prioritize immediate popular needs over institutional traditions often face backlash despite achieving substantive good. This tension remains germane in democracies today, making Flaminius's story not just a historical case study but a mirror for contemporary political dilemmas.

Conclusion: The Road That Outlasted the Man

Two millennia later, the physical legacy of Gaius Flaminius endures where reputations faded. Drivers on Italy's modern Strada Statale 3 retrace his engineered path through the Apennines. Tourists in Rome stroll past the reconstructed Temple of Mars where he allegedly ignored omens. Yet perhaps his truest monument is the enduring idea he represented—that leaders must sometimes challenge entrenched powers to serve broader interests. In death, Flaminius became more than a failed general; he transformed into an eternal question about the price of progress and who gets to write its history. As historians continue reassessing his life, one truth remains: Rome's greatest defeats often taught its most enduring lessons.

Comments