Alexandre Yersin: The Pioneering Scientist Who Conquered the Plague

Introduction: A Life of Exploration and Discovery

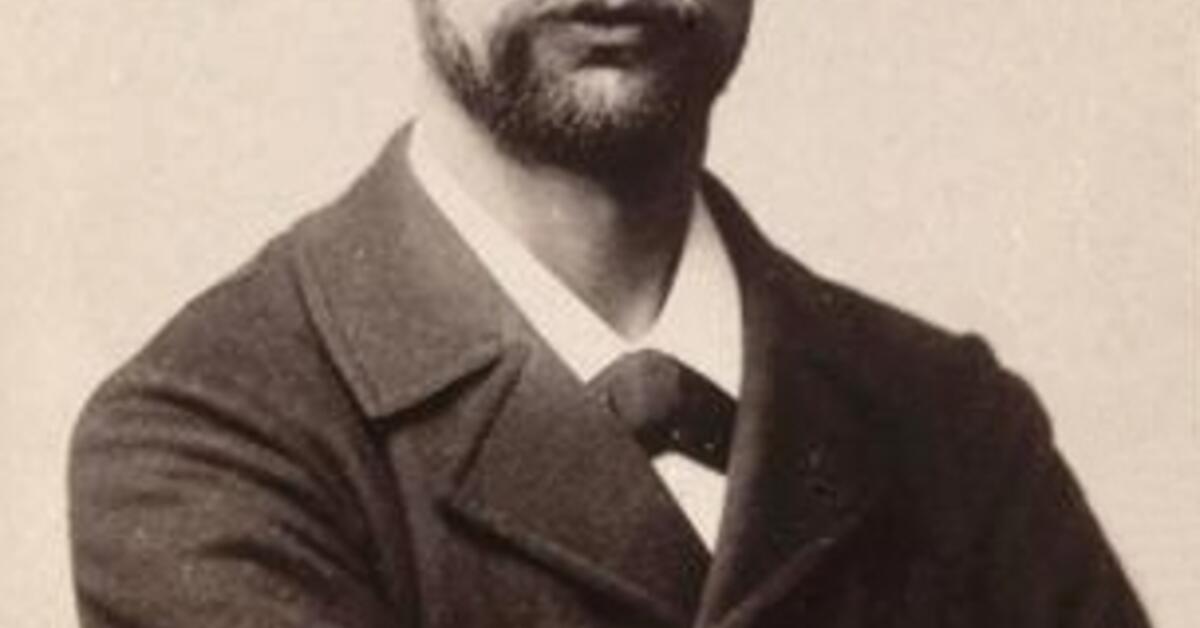

Alexandre Yersin was a Swiss-French physician, bacteriologist, and explorer whose groundbreaking work in microbiology saved countless lives. Born in 1863 in Aubonne, Switzerland, Yersin’s insatiable curiosity led him to contribute immensely to the fields of medicine, epidemiology, and even agriculture. Best known for his discovery of the bacterium responsible for the bubonic plague—Yersinia pestis, named in his honor—his legacy extends far beyond a single scientific achievement.

This first part of the article explores Yersin’s early life, education, and the pivotal discoveries that cemented his place in medical history.

Early Years and Academic Pursuits

Yersin’s journey began in the small town of Aubonne, where he was raised by his mother after his father’s untimely death. Despite financial struggles, his intellectual brilliance shone early, leading him to pursue medical studies in Germany and Switzerland. He later moved to France and enrolled at the prestigious Pasteur Institute in Paris, where he worked under the mentorship of Louis Pasteur and Émile Roux.

At the institute, Yersin quickly distinguished himself. He collaborated with Roux on research into diphtheria, co-discovering the diphtheria toxin, which became a cornerstone in the development of antitoxin therapies. His meticulous laboratory techniques and keen observational skills set the stage for his later groundbreaking work.

The Journey to Indochina and the Plague Breakthrough

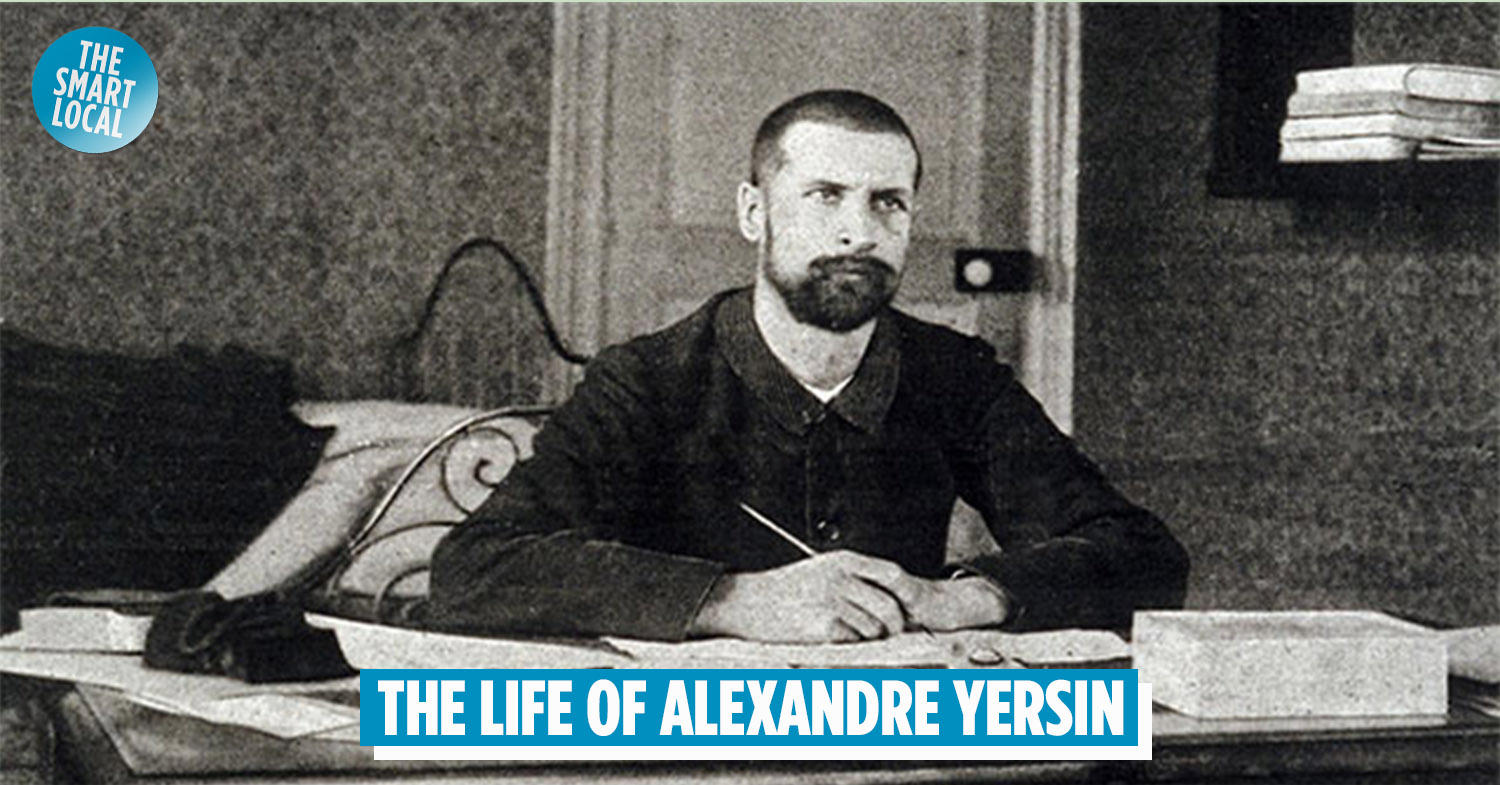

Restless and adventurous, Yersin longed to explore beyond Europe. In 1890, he joined the French Colonial Health Service and traveled to French Indochina (modern-day Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia). Stationed in Nha Trang, he combined his medical duties with exploration, becoming one of the first Europeans to traverse the Annamite Range—a rugged mountainous region dividing Vietnam and Laos.

In 1894, an outbreak of bubonic plague in Hong Kong drew Yersin’s attention. Scientists worldwide were scrambling to identify the cause, but Yersin’s approach proved decisive. Setting up a makeshift lab near the overcrowded hospitals, he examined the fluid from buboes (swollen lymph nodes) of infected patients. Using limited resources, he isolated and identified the rod-shaped bacterium responsible for the disease.

His discovery conflicted with the findings of Japanese scientist Kitasato Shibasaburō, who had also studied the plague. However, modern research confirmed Yersin’s work as accurate—the bacterium was later renamed Yersinia pestis in his honor.

Contributions Beyond the Plague: Agriculture and Public Health

Though his plague discovery was monumental, Yersin’s contributions didn’t stop there. Recognizing the economic struggles of rural Vietnamese communities, he introduced cash crops like rubber and quinine-producing cinchona trees to the region. His agrarian experiments transformed Nha Trang into an agricultural hub, improving local livelihoods.

Additionally, he established the Pasteur Institute in Nha Trang in 1895, later expanding its branches across Indochina. These institutes became vital centers for vaccine production and disease research, combating malaria, rabies, and smallpox.

A Legacy of Humility and Dedication

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Yersin shunned fame. He lived modestly, preferring the company of local farmers and fellow researchers over academic accolades. Even when nominated for the Nobel Prize, he reportedly showed little interest, focusing instead on practical scientific work.

His deep respect for Vietnamese culture and people set him apart from other colonial figures. Fluent in Vietnamese, he integrated into local communities, earning enduring admiration. Today, streets, schools, and hospitals in Vietnam bear his name, a testament to his lasting impact.

Conclusion of Part One

This first section has traced Alexandre Yersin’s early life, education, and his pivotal role in identifying Yersinia pestis. Yet, his story is far from over. In the next part, we’ll delve deeper into his later years, his influence on tropical medicine, and how his work continues to resonate in modern science.

(To be continued...)

The Later Years: Yersin’s Enduring Impact on Tropical Medicine

After his monumental discovery of Yersinia pestis, Alexandre Yersin continued his work with relentless dedication. His later years were marked by further scientific exploration, the establishment of key medical institutions, and a deepening connection with the land and people of Indochina. This second part of the article delves into his post-plague contributions, his role in shaping modern tropical medicine, and the personal philosophy that guided his remarkable life.

Establishing the Pasteur Institutes of Indochina

Yersin’s vision extended beyond laboratory discoveries—he sought to create sustainable systems for public health. Recognizing the rampant spread of infectious diseases in colonial Indochina, he spearheaded the creation of multiple Pasteur Institutes. Beginning with Nha Trang in 1895, he later expanded to Hanoi (1925) and Dalat (1936). These institutes were not mere research centers; they became lifelines for local populations.

The Nha Trang branch, in particular, emerged as a hub for vaccine production. Yersin oversaw the development of vaccines for rabies, smallpox, and cholera, ensuring they were affordable and accessible. His institutes also trained local medical professionals, fostering a new generation of Vietnamese scientists and doctors. Unlike many colonial administrators, Yersin believed in empowering indigenous communities rather than imposing foreign systems upon them.

Pioneering Work in Sericulture and Veterinary Medicine

Yersin’s curiosity wasn’t confined to human health. He saw agriculture as another avenue to improve livelihoods. Intrigued by sericulture (silkworm farming), he introduced advanced techniques to Vietnamese farmers, helping revitalize a struggling industry. His research on silkworm diseases prevented catastrophic outbreaks that could have devastated local economies.

Similarly, he tackled livestock health, studying cattle plagues and developing vaccines for animal diseases. His veterinary work ensured food security for rural populations, demonstrating his holistic approach to public welfare.

The Dalat Years: A Sanctuary for Science and Reflection

In 1915, Yersin moved to the highland city of Dalat, where the cooler climate better suited his health. There, he built a laboratory and continued his research, focusing on meteorology, astronomy, and botany. His passion for farming flourished—he experimented with new crops, including coffee, tea, and exotic fruits, transforming Dalat into an agricultural research center.

His home in Dalat, a modest wooden house surrounded by gardens, became a retreat for visiting scientists. Unlike the opulent residences of colonial officials, Yersin’s dwelling reflected his simplicity. He lived without extravagance, reinvesting his earnings into research and community projects.

A Reluctant Legend: Yersin’s Humility and Philosophy

Despite his achievements, Yersin remained strikingly humble. He declined high-ranking positions, including directorship offers from European institutions, preferring the solitude of his Indochinese labs. His correspondence reveals a man more interested in solving practical problems than chasing fame. In a letter to his mother, he wrote:

“What matters is not the recognition, but the work itself—the chance to alleviate suffering and uncover truth.”

This ethos defined his career. While contemporaries like Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch became household names, Yersin’s renown was quieter but no less profound. He rejected the racial prejudices of his time, treating Vietnamese colleagues as equals—a rarity in the colonial era.

The Nobel Controversy and Unfinished Research

Yersin was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine multiple times, yet he never won. Some historians speculate that his reluctance to engage in academic politics and his remote location in Indochina worked against him. Others argue that the Nobel Committee overlooked his broader contributions because they were spread across too many fields—bacteriology, agriculture, and public health.

In his final years, Yersin continued studying tetanus and malaria, hoping to develop new treatments. Though age slowed him, his mind remained sharp. He meticulously documented his observations, leaving behind unpublished manuscripts that hinted at unexplored breakthroughs.

Death and Posthumous Honors

Alexandre Yersin passed away on March 1, 1943, in Nha Trang at the age of 79. His funeral was attended by thousands—locals, scientists, and government officials alike. In a rare honor, the Vietnamese buried him on a hill overlooking the Pasteur Institute, a place he had cherished.

Today, Yersin’s legacy thrives. Vietnam celebrates him as a national hero; streets, schools, and even a university bear his name. The Pasteur Institutes he founded still operate, now under Vietnamese management, continuing his fight against infectious diseases.

Conclusion of Part Two

This section has explored Yersin’s later contributions, from institutional building to agricultural innovation, and the quiet philosophy that guided him. Yet, his influence extends further—into modern medicine, cultural memory, and even space exploration. The final part of this article will examine Yersin’s global legacy, his portrayal in popular culture, and why his work remains relevant in the 21st century.

(To be continued...)

Alexandre Yersin's Eternal Legacy: A Bridge Between Centuries

From Plague to Pandemics: Yersin's Relevance in Modern Medicine

While Yersin identified Yersinia pestis in the 19th century, his methodologies remain shockingly relevant today. His approach—combining field epidemiology with laboratory precision—created the blueprint for modern outbreak responses. During the COVID-19 pandemic, scientists explicitly referenced his Hong Kong plague research as they grappled with viral transmission patterns.

The Pasteur Institutes he founded became crucial players in Vietnam's successful COVID containment strategy. Their rapid development of testing protocols mirrored Yersin's own crisis responses over a century earlier. Notably, researchers at these institutes sequenced SARS-CoV-2 variants faster than many Western counterparts—a direct lineage to Yersin's emphasis on decentralized scientific capacity.

Space Farms and Planetary Science: An Unexpected Legacy

Few know that Yersin's agricultural experiments still influence extraterrestrial research. NASA's Controlled Ecological Life Support System (CELSS) programs cite his tropical farming innovations as inspiration for closed-loop food production. His work on compact, high-yield crop rotations informs designs for Martian colony agriculture.

In 2021, Vietnamese researchers honored this connection by growing Yersin's drought-resistant coffee varietals aboard the International Space Station. The experiment succeeded—proving that his century-old agricultural insights could sustain future space explorers.

The Cultural Icon: Yersin in Vietnamese Consciousness

Unlike most colonial-era Europeans, Yersin enjoys near-mythic status in Vietnam. Elementary students learn his name alongside national heroes like Trần Hưng Đạo. His birthday (September 22) sees pilgrimages to his Nha Trang tomb, where locals leave offerings of fruit from trees he introduced.

This cultural adoption manifests in surprising ways:

- Yersin-themed cafes serve quinine-infused cocktails using his cinchona bark recipes

- A viral TikTok trend showcases "Yersin cosplay" with vintage lab coats and microscopes

- Vietnamese sci-fi writers cast him as a time-traveling protagonist curing future plagues

The government has petitioned UNESCO to recognize his Nha Trang residence as a World Heritage Site—an unprecedented honor for a foreign-born scientist.

Debates and Reassessments: The Colonial Context Reexamined

Recent scholarship has sparked nuanced debates about Yersin's colonial context. While he rejected racial hierarchies, his institutes undeniably operated within France's imperial framework. Some historians argue:

"Yersin represented a paradox—a man who genuinely loved Vietnam yet benefited from colonial structures. His veterinary vaccines increased livestock productivity that primarily served French rubber plantations."

Others counter that his grassroots focus and cultural integration transcended typical colonial dynamics. The controversy highlights how even progressive historical figures require contextual understanding.

Yersin's Scientific "Children": Tracing His Academic Lineage

The bacteriologist's mentorship created an unbroken chain of influence:

- Early Vietnamese Pasteur Institute trainees established the country's first medical schools

- Swiss proteges like Édouard Bugnion expanded tropical medicine research globally

- Modern plague researchers still use Yersin's original strain collections for comparative genomics

A 2023 study in The Lancet tracked over 12,000 active biomedical professionals who can trace their academic genealogy back to Yersin—a testament to institutional sustainability.

Future Horizons: Yersin-Inspired Innovations

Cutting-edge projects continue drawing from Yersin's interdisciplinary approach:

| Field | Innovation | Yersin Connection |

|---|---|---|

| Biodefense | Plague-resistant CRISPR modifications | Using his Y. pestis samples |

| Climate Adaptation | Drought-resistant coffee hybrids | Based on his Dalat cultivars |

| AI Epidemiology | Outbreak prediction algorithms | Modeled on his field notes |

The Pasteur Institute recently unveiled Project Yersinia 2.0—a digital twin of his research that uses machine learning to simulate hypothetical discoveries he might have made with modern tools.

Conclusion: The Timeless Scientist

Alexandre Yersin endures as perhaps history's most versatile applied scientist. Unlike contemporaries who specialized narrowly, his genius flowed freely between microscopes and crop fields, between European labs and Asian jungles. In an age of hyper-specialization, his example argues for the power of cross-disciplinary curiosity.

The COVID era revived global appreciation for his methods, while space-age adaptations of his agricultural work point to a legacy stretching into humanity's future. Whether through Vietnamese schoolchildren tending plague memorials or astronauts drinking coffee grown from his seeds, Yersin's spirit persists—a quiet force still shaping our world.

His final diary entry, written weeks before his death, perhaps says it best:

"The microscope shows us microbes, but true vision sees how all things connect."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1f/6b/1f6be1c6-ec72-46e3-86c8-38ae4038d098/stukeley.jpg)

Comments