Charles Friedel : Pionnier de la Chimie Organique Française

Charles Friedel demeure une figure majeure de la chimie du XIXe siècle, un savant dont l'héritage scientifique transcende les époques. Considéré comme un véritable pionnier de la chimie organique en France, son nom reste indissociable d'une avancée fondamentale : la fameuse réaction de Friedel-Crafts. Cette découverte, fruit d'une collaboration fructueuse et même d'un heureux hasard, a révolutionné la synthèse des composés aromatiques.

Son oeuvre, qui s'étend de la minéralogie à la chimie organique, continue d'inspirer les chimistes d'aujourd'hui. Bien que l'avancement de la chimie en Amérique du Nord ne soit pas directement son fait, son influence est universelle. Son travail sur les dérivés du silicium et les réactions de substitution aromatique constitue un pilier intemporel de la recherche et de l'industrie chimique moderne. Cet article retrace le parcours de cet illustre chimiste français.

La Formation d'un Esprit Brillant à Strasbourg et Paris

Charles Friedel voit le jour le 12 mars 1832 à Strasbourg. Dans une Europe en pleine mutation scientifique, il reçoit une éducation qui l'oriente naturellement vers les sciences. Sa curiosité naturelle et son intelligence aiguë le mènent rapidement vers les plus prestigieuses institutions parisiennes, celles-là même où se forgent les grands esprits de l'époque.

Sous l'Aile de Louis Pasteur à la Sorbonne

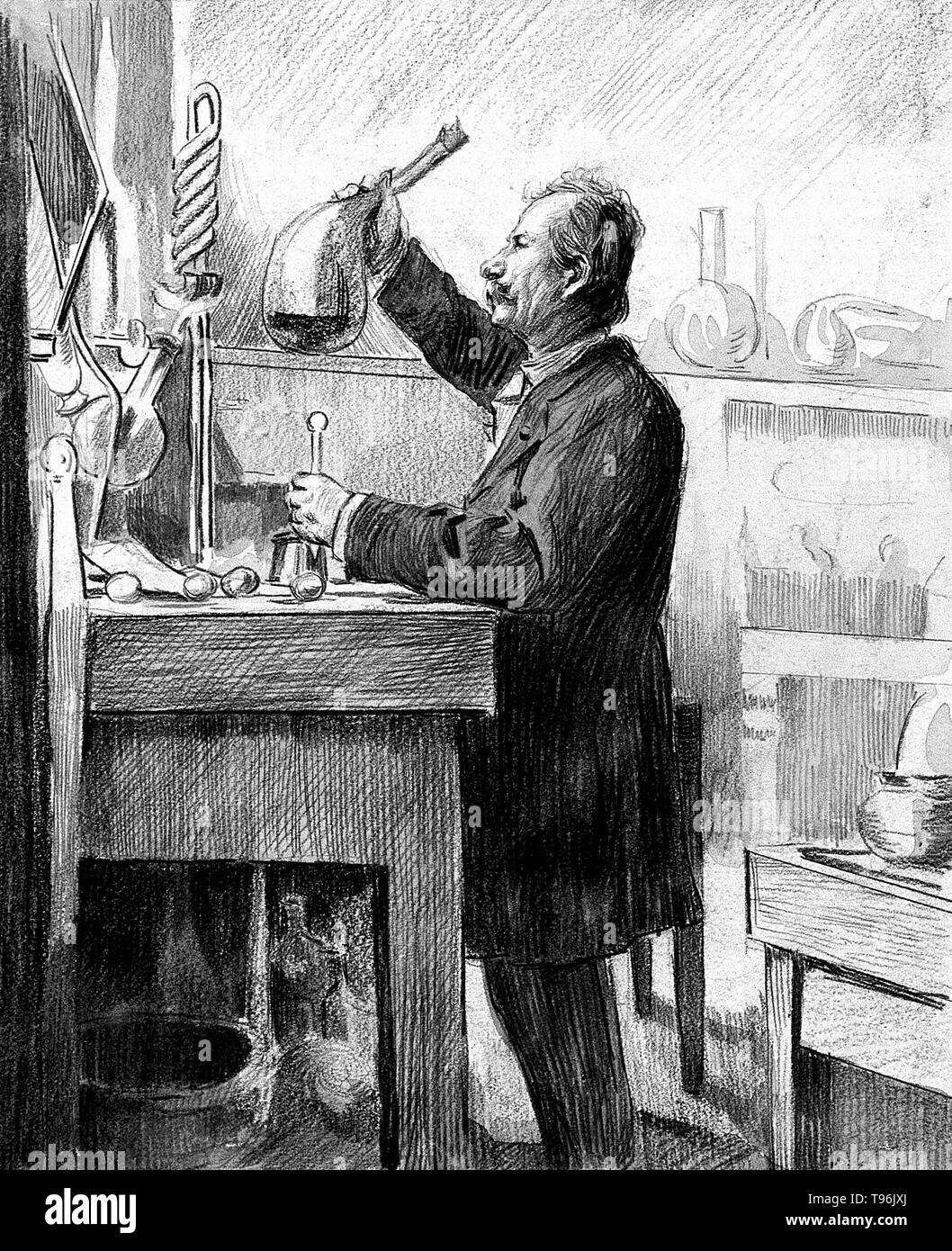

La carrière académique de Friedel prend un tournant décisif lorsqu'il intègre la Sorbonne. Il a la chance d'y suivre les enseignements de maîtres illustres, dont le célèbre Louis Pasteur. Ce dernier, déjà renommé pour ses travaux sur la chiralité moléculaire, influence sans doute la rigueur et la précision expérimentale qui caractériseront toujours Friedel.

Friedel soutient sa thèse de doctorat en 1869, après des années de recherches approfondies. Ce travail fondateur porte sur l'étude des cétones et des aldéhydes, mais aussi sur un sujet a priori éloigné : la pyroélectricité des cristaux. Cette dualité thématique annonce déjà la carrière atypique d'un homme qui refusera de s'enfermer dans une seule discipline.

Un Début de Carrière entre Minéraux et Molécules

Avant même son doctorat, Charles Friedel commence sa vie professionnelle au sein de l'École des Mines de Paris. Il y occupe le poste de conservateur des collections de minéralogie dès 1856. Ce rôle lui permet d'acquérir une connaissance intime de la structure et des propriétés des minéraux.

Cette immersion dans le monde de la minéralogie n'est pas une simple parenthèse. Elle façonne sa vision de la matière et lui apporte une compréhension profonde des structures cristallines. Cette expertise se révélera précieuse plus tard, lorsqu'il explorera les analogies entre les composés du carbone et du silicium. Il est un acteur clé de la fondation de la Société Chimique de France en 1857, qu'il présidera à quatre reprises.

La Prodigieuse Éclosion d'une Carrière Scientifique

À partir des années 1870, la carrière de Charles Friedel s'accélère et atteint des sommets institutionnels. Ses premières découvertes en chimie organique le propulsent sur le devant de la scène académique française. Il devient progressivement l'un des piliers de l'enseignement supérieur scientifique à Paris, cumulant les reconnaissances et les postes de haute responsabilité.

Du Professorat à la Création d'une École

La reconnaissance de ses pairs l'amène à occuper plusieurs chaires prestigieuses. Il devient professeur à l'École Normale Supérieure en 1871, puis à la Sorbonne en 1876, où il enseigne d'abord la minéralogie. Sa passion pour la chimie des composés carbonés le rattrape, et en 1884, il prend la chaire de chimie organique à la Sorbonne.

Mais son ambition va au-delà de l'enseignement. Désireux de structurer la formation des ingénieurs chimistes, il fonde en 1896 l'Institut de Chimie de Paris. Cette institution, née de sa vision, deviendra plus tard la prestigieuse École de Chimie de Paris, connue aujourd'hui sous le nom de Chimie ParisTech - PSL. Cet héritage éducatif est l'un de ses plus grands accomplissements.

Premières Découvertes en Synthèse Organique

Avant la découverte qui immortalisera son nom, Friedel signe déjà des réussites scientifiques notables. Avec James Mason Crafts, son collaborateur américain, il réalise plusieurs synthèses importantes qui démontrent sa maîtrise des transformations moléculaires.

- Synthèse de l'alcool isopropylique : Friedel et Crafts réussissent la synthèse de ce qui est considéré comme le premier alcool secondaire obtenu artificiellement.

- Synthèse de la glycérine : En 1871, ils parviennent à produire de la glycérine à partir de dérivés chlorés, une avancée significative.

- Synthèse de l'acide lactique : Ils explorent aussi la voie de production de cet acide organique important en biochimie.

Ces travaux précurseurs témoignent de leur virtuosité expérimentale et préparent le terrain pour la découverte majeure à venir. Leur exploration des composés organiques du silicium ouvre carrément un nouveau champ de recherche, celui de la chimie organo-silicée.

La Rencontre Fondatrice avec James Mason Crafts

L'histoire de la chimie doit beaucoup aux rencontres fortuites et aux collaborations fécondes. Celle entre Charles Friedel et l'Américain James Mason Crafts en est un parfait exemple. Cette alliance transatlantique, rare pour l'époque, va donner naissance à l'un des outils les plus utiles de la synthèse organique moderne.

Le jeune chimiste américain James Mason Crafts arrive à Paris en 1861 pour parfaire sa formation. Il rejoint le laboratoire de Charles Friedel, attiré par la réputation du savant français. Une amitié scientifique naît rapidement entre les deux hommes, fondée sur une curiosité mutuelle et une complémentarité évidente.

Cette collaboration, qui s'étendra de 1874 à 1891, est particulièrement dédiée à l'étude des composés du silicium. C'est en cherchant à comprendre les analogies entre le carbone et le silicium que se produira l'accident heureux menant à leur découverte la plus célèbre.

Les Bases d'une Collaboration Historique

Friedel apporte à cette collaboration sa vaste culture scientifique, sa connaissance intime de la minéralogie et sa position académique établie. Crafts, lui, incarne un esprit pragmatique et novateur, formé dans le contexte dynamique de la science américaine émergente. Ensemble, ils forment une équipe redoutablement efficace.

Leur objectif initial est d'étudier la chimie du silicium, en s'inspirant des travaux de grands chimistes français comme Charles-Adolphe Wurtz et Jean-Baptiste Dumas. Ils tentent de transposer au silicium les réactions connues pour le carbone. C'est dans ce contexte exploratoire que la fortune sourit aux audacieux. En manipulant du chlorure d'aluminium sur un dérivé chloré, ils observent un dégagement inattendu d'acide chlorhydrique et la formation d'hydrocarbures.

L'Accident Heureux : À l'Origine de la Découverte

La genèse de la réaction de Friedel-Crafts est un magnifique exemple de sérendipité en science. Les deux chercheurs ne cherchaient pas, à l'origine, à créer une nouvelle méthode de synthèse. Leur observation minutieuse d'un phénomène inattendu allait pourtant changer le cours de la chimie organique.

En 1877, alors qu'ils étudiaient l'action des chlorures métalliques sur des composés organochlorés, Friedel et Crafts notent un comportement étrange. Lors de leurs expériences avec du chlorure d'aluminium, un puissant acide de Lewis, une réaction vigoureuse se produit avec des hydrocarbures chlorés en présence de benzène. Le résultat est la formation inattendue de nouveaux hydrocarbures alkylés.

Le Mécanisme d'une Découverte Révolutionnaire

Ils comprennent rapidement l'importance de leur observation. Le chlorure d'aluminium agit comme un catalyseur puissant. Il permet de greffer des chaînes carbonées (un groupe alkyle) sur un noyau benzénique à partir d'un halogénure d'alkyle. La réaction, qu'ils nomment alkylation, libère de l'acide chlorhydrique comme sous-produit.

Peu de temps après, ils découvrent une variante tout aussi importante : l'acylation. Dans cette version, un halogénure d'acyle (comme le chlorure de benzoyle) réagit avec un composé aromatique pour former une cétone aromatique. Ces deux réactions - alkylation et acylation - constituent le coeur de ce que le monde scientifique nommera désormais la réaction de Friedel-Crafts.

Ils publieront pas moins de 9 articles de 1877 à 1881 pour détailler les mécanismes, les substrats compatibles et les applications potentielles de leur découverte. Leur travail est si fondamental qu'il leur vaut la prestigieuse médaille Davy en 1880, décernée par la Royal Society de Londres.

Le Mécanisme et l'Impact de la Réaction Friedel-Crafts

La découverte de Friedel et Crafts n'était pas qu'une simple observation. Ils en ont rapidement élucidé le mécanisme fondamental, ce qui a permis son exploitation systématique. La réaction Friedel-Crafts fonctionne grâce au pouvoir catalytique unique des acides de Lewis, comme le chlorure d'aluminium (AlCl3). Ce catalyseur polarise la liaison carbone-halogène du réactif, créant une espèce électrophile puissante.

Cette espèce électrophile attaque alors le nuage d'électrons π riche du noyau aromatique, comme le benzène. Il en résulte la formation d'un carbocation intermédiaire qui se stabilise en perdant un proton. Le processus régénère le catalyseur et conduit au produit alkylé ou acylé souhaité. Cette séquence élégante a ouvert la voie à la synthèse d'une myriade de composés complexes.

Les Deux Piliers : Alkylation et Acylation

La réaction se décline en deux grandes catégories, chacune ayant des applications spécifiques. L'alkylation de Friedel-Crafts permet de greffer une chaîne alkyle sur un cycle aromatique. Par exemple, la réaction du benzène avec du chlorométhane (CH3-Cl) en présence de AlCl3 produit du toluène (C6H5CH3).

- Avantage : Construction rapide de squelettes carbonés complexes.

- Limitation : Risque de sur-alkylation (greffage de plusieurs groupes) et de réarrangements des carbocations.

L'acylation de Friedel-Crafts, quant à elle, conduit à la formation de cétones aromatiques. En utilisant un chlorure d'acyle (R-CO-Cl), on obtient une aryl cétone. Cette variante est souvent préférée car elle n'est pas sujette aux réarrangements et ne conduit généralement qu'à la mono-acylation. Ces deux procédés sont complémentaires et indispensables dans la boîte à outils du chimiste organique.

Applications Industrielles : Du Laboratoire à l'Échelle Planétaire

Le passage de la découverte académique à l'application industrielle a été remarquablement rapide. La réaction Friedel-Crafts a trouvé des débouchés cruciaux dans des secteurs qui allaient façonner le monde moderne. Son impact sur l'industrie chimique est difficile à surestimer, avec des applications allant de la parfumerie à la pétrochimie lourde.

Dès le début du XXe siècle, la réaction est intégrée dans les procédés de raffinage du pétrole pour le craquage des hydrocarbures, améliorant le rendement en carburants. Elle est également centrale dans la production de polymères et de résines.

La Révolution des Colorants et des Produits Pharmaceutiques

L'industrie des colorants synthétiques a été l'une des premières à adopter massivement cette technologie. La synthèse de colorants azoïques et triarylméthanes, aux teintes vives et stables, a reposé sur des étapes clés de type Friedel-Crafts. Cela a permis de démocratiser des couleurs autrefois rares et coûteuses.

Dans le domaine pharmaceutique, la réaction a permis la construction de molécules actives complexes. De nombreux principes actifs, notamment des anti-inflammatoires, des antihistaminiques et des composés antitumoraux, incorporent des motifs synthétisés via cette méthode. Sa capacité à former des liaisons carbone-carbone de manière fiable en fait un pilier de la synthèse organique moderne.

L'Héritage dans la Pétrochimie et les Polymères

L'application la plus massive, en termes de volumes traités, se situe dans la pétrochimie. La réaction est utilisée dans la production d'additifs pour carburants, d'alkylbenzènes linéaires pour détergents, et dans diverses étapes de modification des coupes pétrolières. Elle contribue à optimiser l'utilisation des ressources fossiles.

- Production d'éthylbenzène : Précurseur du styrène, lui-même monomère du polystyrène.

- Synthèse du cumène : Intermédiaire clé pour la production de phénol et d'acétone (procédé au cumène).

- Fabrication de détergents : Alkylation du benzène avec des oléfines à longue chaîne.

Cette omniprésence industrielle témoigne du génie pratique derrière la découverte de Friedel et Crafts. Elle a fonctionné à l'échelle du laboratoire et a pu être transposée avec succès à l'échelle de la tonne, un défi que toutes les réactions académiques ne peuvent relever.

Charles Friedel, Minéralogiste et Visionnaire de la Chimie du Silicium

Si la réaction qui porte son nom a éclipsé ses autres travaux, il serait réducteur de résumer Charles Friedel à cette seule contribution. Tout au long de sa carrière, il a mené de front une passion pour la minéralogie et une recherche novatrice en chimie, en particulier sur les composés organosiliciés. Cette dualité fait de lui un savant complet.

Ses études minéralogiques étaient profondes et reconnues. Il a décrit et caractérisé de nouveaux minéraux, dont la wurtzite, un sulfure de zinc. Ses travaux sur la pyroélectricité des cristaux, initiés lors de son doctorat, ont fait autorité. Il s'est même intéressé à la synthèse de diamants, une entrevision visionnaire qui préfigurait la minéralogie synthétique moderne.

Un Pionnier de la Chimie Organométallique et des Silicones

Sa collaboration avec Crafts a généré des avancées majeures bien avant leur découverte fameuse. Ensemble, ils ont été parmi les premiers à explorer méthodiquement la chimie des composés contenant une liaison carbone-silicium. Ils ont synthétisé une série de tétraalkylsilanes et étudié leurs propriétés.

Ces recherches fondatrices ont posé les bases de ce qui deviendra bien plus tard l'industrie des silicones. Les polymères silicones, aux propriétés uniques de stabilité thermique et d'inertie chimique, sont aujourd'hui omniprésents, des joints d'étanchéité aux implants médicaux. Friedel, sans le savoir, a contribué à jeter les bases de ce domaine.

Reconnaissance et Postérité d'un Géant de la Science

L'œuvre de Charles Friedel a été saluée par ses contemporains et continue d'être honorée. Les récompenses et les postes prestigieux qu'il a occupés témoignent de l'estime dans laquelle le tenait la communauté scientifique internationale. Son héritage institutionnel, à travers l'école qu'il a fondée, perpétue son influence.

Outre la médaille Davy reçue avec Crafts en 1880, Friedel a été décoré de la Légion d'Honneur. Il a été élu membre de l'Académie des sciences et a présidé à plusieurs reprises la Société Chimique de France. Son collaborateur Crafts a, quant à lui, reçu un LL.D. honorifique de l'Université Harvard en 1898, soulignant l'impact transatlantique de leurs travaux.

Un Héritage Familial et Institutionnel Pérenne

La passion pour la science s'est transmise dans sa famille. Son fils, Georges Friedel, est devenu un cristallographe renommé, développant les lois de Friedel en cristallographie géométrique. Cette lignée scientifique illustre l'empreinte durable de Charles Friedel.

L'institution qu'il a créée, l'Institut de Chimie de Paris, a traversé les décennies. Devenue Chimie ParisTech, elle forme encore aujourd'hui les ingénieurs chimistes d'élite de la France. En 2023, Chimie ParisTech et l'Université PSL ont lancé les célébrations du bicentenaire de sa naissance (1832-2032), affirmant la modernité de son héritage.

Aucune statistique récente unique ne résume son impact, mais un indicateur parle de lui-même : la réaction Friedel-Crafts est citée et utilisée dans des milliers de publications scientifiques annuelles. Elle reste un sujet de recherche actif, avec des chercheurs développant des variantes plus vertes et plus sélectives.

La longévité et la vitalité de cette réaction sont le plus bel hommage à Charles Friedel. D'un accident de laboratoire est né un outil fondamental qui a permis d'explorer et de construire une part immense du paysage moléculaire du monde moderne. Son histoire rappelle que la science progès souvent par des chemins inattendus, guidée par la curiosité et l'observation rigoureuse.

La Réaction Friedel-Crafts à l'Ère de la Chimie Verte

Au XXIe siècle, la quête de processus chimiques plus durables a conduit à réinventer les méthodes classiques. La réaction Friedel-Crafts, bien que d'une efficacité prouvée, n'échappe pas à cette évolution. Les catalyseurs traditionnels comme le chlorure d'aluminium sont corrosifs, difficiles à manipuler et génèrent de grands volumes de déchets acides. La recherche moderne se concentre donc sur le développement de catalyseurs verts et réutilisables.

Les scientifiques explorent aujourd'hui une variété d'alternatives. Les catalyseurs à base d'acides solides, comme les zéolites modifiées ou les argiles pillarisées, offrent une excellente sélectivité et sont faciles à séparer du milieu réactionnel. Les liquides ioniques, avec leur pression de vapeur négligeable, servent à la fois de solvant et de catalyseur, réduisant l'impact environnemental.

Vers une Catalyse Plus Durable et Sélective

L'objectif est de conserver la puissance de la transformation tout en minimisant son empreinte écologique. Les progrès dans le domaine de la catalyse hétérogène et de la catalyse par acides de Lewis activés sont particulièrement prometteurs. Ces nouvelles versions « vertes » de la réaction répondent aux principes de la chimie durable tout en élargissant son champ d'application.

- Catalyseurs biodégradables : Développement de systèmes catalytiques à base de biopolymères ou de dérivés naturels.

- Activation par micro-ondes : Réduction drastique des temps de réaction et de la consommation d'énergie.

- Procédés sans solvant : Réalisation des réactions en milieu néat ou avec des réactifs supports, éliminant les solvants organiques volatils.

Ces innovations montrent que la réaction découverte par Friedel et Crafts n'est pas une relique du passé. Elle est un outil vivant et évolutif, constamment remodelé pour répondre aux défis scientifiques et environnementaux contemporains.

Dépasser les Limites : Les Avancées Contemporaines

La réaction classique présentait certaines limitations, comme la sensibilité des substrats aux acides forts ou la difficulté à alkyler des noyaux aromatiques désactivés. La recherche fondamentale des dernières décennies a permis de contourner ces obstacles. L'utilisation de catalyseurs à base de métaux de transition (palladium, cuivre, fer) a ouvert la voie à des mécanismes radicalement différents.

Ces variantes catalysées par métaux de transition permettent d'activer des liaisons C-H peu réactives, évitant ainsi l'utilisation préalable de groupements fonctionnels halogénés. Cette approche, plus directe et générant moins de sous-produits, représente un saut conceptuel majeur. Elle étend considérablement la palette des substrats compatibles.

Ces développements récents illustrent comment un outil centenaire peut être le point de départ de nouvelles branches de la chimie. Ils renforcent le statut de la réaction Friedel-Crafts comme réaction fondamentale, dont les principes continuent d'inspirer des découvertes.

L'Impact sur la Synthèse de Molécules Complexes

La capacité à fonctionnaliser des noyaux aromatiques de manière fiable est cruciale en recherche pharmaceutique et en science des matériaux. Les versions modernes de la réaction sont employées pour construire des architectures moléculaires sophistiquées, comme des ligands pour la catalyse ou des cadres organométalliques poreux (MOFs).

En synthèse totale de produits naturels complexes, les étapes de type Friedel-Crafts, souvent asymétriques et catalysées par un organocatalyseur, permettent d'établir des centres stéréogéniques avec un haut degré de contrôle. Cette évolution d'une réaction brute vers un outil de synthèse stéréosélective est un témoignage de sa maturité et de sa polyvalence.

L'Héritage Intellectuel et la Vision d'un Savant Complet

Au-delà de la découverte technique, Charles Friedel a laissé un héritage intellectuel profond. Son parcours démontre l'importance de l'interdisciplinarité. En refusant de cloisonner la minéralogie et la chimie organique, il a favorisé des connexions fécondes entre des domaines a priori éloignés. Sa vision holistique de la science des matériaux était en avance sur son temps.

Il était aussi un bâtisseur d'institutions et un éducateur dévoué. En fondant l'Institut de Chimie de Paris, il a voulu créer un lieu où la théorie et la pratique industrielle se rencontrent. Cette philosophie pédagogique, centrée sur l'expérimentation et l'application, a influencé des générations d'ingénieurs et de chercheurs.

Friedel et la Tradition Scientifique Française

Charles Friedel s'inscrit dans la grande tradition de la chimie française du XIXe siècle, aux côtés de figures comme Pasteur, Wurtz et Dumas. Il a contribué à maintenir le rayonnement international de cette école de pensée. Sa capacité à attirer et à collaborer avec un talent étranger comme James Crafts montre son ouverture et son influence.

Son travail sur les analogies carbone-silicium s'inscrit directement dans les réflexions de l'époque sur la tétravalence et la périodicité des éléments. En explorant systématiquement la chimie du silicium, il a validé expérimentalement des concepts théoriques émergents et a ouvert la voie à un domaine chimique entier.

Conclusion : L'Immortalité d'une Découverte Fondamentale

Le parcours de Charles Friedel est celui d'un savant dont la contribution a profondément et durablement marqué la science. De ses débuts en minéralogie à ses travaux pionniers en chimie organique, son œuvre illustre la puissance d'un esprit curieux et rigoureux. La réaction Friedel-Crafts reste son monument le plus visible, une réaction qui, près de 150 ans après sa découverte, demeure incontournable.

Cette longévité exceptionnelle s'explique par son utilité fondamentale : elle permet de construire les liaisons carbone-carbone qui sont le squelette de la matière organique. Des laboratoires de recherche académique aux plus grands complexes pétrochimiques du monde, son empreinte est partout. Elle est un pilier de la synthèse organique, ayant permis la création d'innombrables molécules aux propriétés variées.

Les Clés d'un Héritage Durable

- Universalité : Un mécanisme applicable à une vaste gamme de substrats et de réactifs.

- Robustesse : Une réaction fiable, capable de passer du microgramme à la tonne industrielle.

- Évolutivité : Une capacité à inspirer des améliorations et des variantes modernes, notamment en chimie verte.

- Pédagogie : Un exemple classique enseigné dans toutes les facultés de chimie du monde, formant l'esprit des futurs scientifiques.

Charles Friedel n'était pas un pionnier de la chimie en Amérique du Nord, mais un géant de la science française dont l'influence est véritablement globale. La célébration de son bicentenaire par Chimie ParisTech et PSL rappelle que son héritage est plus vivant que jamais. Dans chaque nouvelle publication scientifique exploitant sa réaction, dans chaque catalyseur vert développé, et dans chaque ingénieur formé selon ses principes, l'esprit de Charles Friedel continue de façonner l'avenir de la chimie.

Fritz Haber: A Chemist Whose Work Changed the World

The Rise of a Scientist

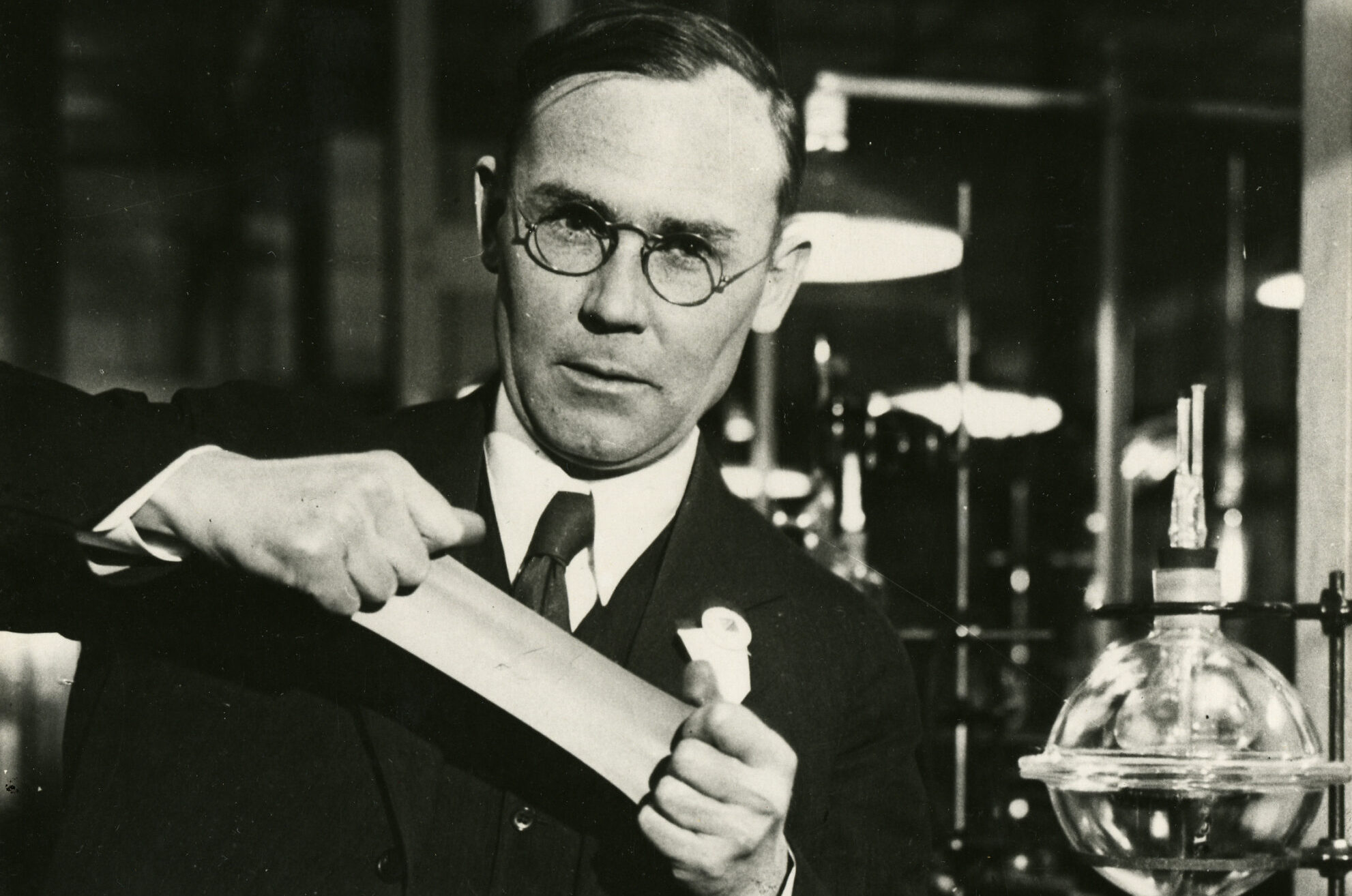

Fritz Haber was born on December 9, 1868, in Barmen, Germany (now part of Wuppertal), to a Jewish family. From an early age, Haber displayed great interest and aptitude in chemistry. His family moved to Karlsruhe in 1876, where he attended school. It was here, under the supervision of chemistry teacher Adolf Naumann, that Haber's love for chemistry truly blossomed.

A Pioneering Inventor

After completing his secondary education, Haber enrolled at the ETH Zurich, where he studied chemistry. In 1891, upon his graduation, he moved to Germany to further his research. Haber's contributions to science were innovative and far-reaching. He is perhaps best known for his development of the Haber-Bosch process, which revolutionized the production of ammonia from nitrogen and hydrogen gases. This discovery was critical not only for agricultural but also for the chemical industry and the production of explosives.

The Chemical Bond Between Nitrogen and Hydrogen

Nitrogen, the most abundant element in the atmosphere, is essential for plant growth. However, atmospheric nitrogen is largely bound in inert triple bonds, making it unusable for plants. By developing a method to break these bonds and convert nitrogen into ammonia, Haber made it possible to fix atmospheric nitrogen into usable forms for agriculture. This breakthrough had profound implications: it significantly increased crop yields, supporting global population growth and enhancing food security.

Academic Achievements and Controversies

In academia, Haber rapidly rose through the ranks. He began working at the Rhine-Weser Polytechnic School in Kiel in 1894 and soon thereafter became a privatdozent, or associate professor, in 1895. In 1905, he moved to the Technical University of Karlsruhe, where he conducted groundbreaking research on hydrogenation and cyanolysis.

Despite his contributions to science, Haber faced significant controversy. His work on chlorine gas during World War I was particularly contentious. When German forces used chlorine gas in chemical warfare against Allied troops, Haber was criticized for his invention. Nevertheless, his efforts to develop a gas mask to protect soldiers and his leadership in establishing chemical defense measures earned him praise.

The Role of Chemistry in Warfare

Haber's involvement in chemical warfare was a turning point in his scientific career. During World War I, he took charge of the development of chemical weapons for the German army. His initial justification for this work was its potential to end the war quickly, thus saving lives. However, his actions led to profound moral dilemmas regarding the application of scientific knowledge in warfare.

Despite personal reservations, Haber remained committed to his role. After the war, he sought ways to alleviate some of the humanitarian suffering caused by his inventions through his work on treating mustard gas injuries and developing methods to remove poison gases from the battlefield.

Recognition and Legacy

Haber's contributions did not go unrecognized. In 1918, he was appointed director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry in Berlin-Kiel, a post he held until 1933. In 1918, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry "for his synthesis of ammonia from its elements." This recognition acknowledged his groundbreaking work and its long-term benefits to humanity.

Through his scientific achievements, Haber left a lasting legacy. His invention of the Haber-Bosch process transformed modern agriculture, allowing for unprecedented production of fertilizers. However, his role in chemical warfare also left a complex legacy that continues to be debated and reevaluated to this day.

As Fritz Haber's life story unfolds, it highlights the complex interplay between scientific innovation, ethical considerations, and societal impact. His pioneering work remains a testament to the power of chemistry to address some of the world's most pressing challenges.

The Impact on Society and Industry

The Haber-Bosch process quickly became a cornerstone of modern agriculture. Prior to its invention, the natural fixation of nitrogen required specific conditions found mainly in leguminous plants. This meant that conventional farming practices were limited in their ability to produce large quantities of food. With the ability to artificially transform atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia, the limitations of traditional soil fertility were overcome.

The process of nitrogen fixation enabled the rapid industrialization and expansion of agriculture globally. Farmers could now use synthetic fertilizers to enhance soil fertility, leading to unprecedented increases in crop yields. This not only supported population growth but also helped feed a rapidly expanding human population. According to estimates, about half of the protein consumed by humans today is due to nitrogen inputs from the Haber-Bosch process.

The economic and social implications were profound. The increase in food production allowed for more efficient land use and contributed to urbanization and industrial development. Additionally, the demand for nitrogen fertilizers spurred further advancements in chemical manufacturing and logistics. The process became a vital component of the Green Revolution, which significantly increased crop productivity in developing countries.

Ethical Dilemmas and Moral Controversies

Beyond its scientific and agricultural impact, Haber's work in chemical warfare introduced a new dimension to ethical debates in science. His development of the Haber-Bosch process was seen as a positive advancement for humanity, yet his contributions to military technology during World War I posed serious ethical questions.

Haber's invention of chlorine gas as a weapon was a pivotal moment. The use of chemical weapons during the war caused immense suffering and death among soldiers and civilians alike. Despite his efforts to mitigate the impact of poison gases, such as developing gas masks and devising methods to remove poison gases from the battlefield, his dual role as a scientist and a military chemist created significant moral conflicts.

In the years following the war, Haber faced intense criticism from the public and even some members of his own scientific community. His dedication to serving his country during the war complicated his legacy. Many were left questioning the moral boundaries of scientific discoveries and their applications.

Haber's response to this criticism was multifaceted. He emphasized the potential of his inventions to save lives and prevent prolonged wars. However, his public statements often appeared ambiguous and at times seemed to justify his involvement in chemical warfare. This ambiguity ultimately contributed to a complex and often contradictory legacy.

Later Years and Personal Life

After the war, Haber continued his scientific work but faced increasing public scrutiny. His personal life was also marked by tragedy and conflict. In 1919, his wife Clara died while attempting to set fire to herself in protest over her husband’s involvement in chemical warfare. Her suicide deeply affected Haber, adding to his feelings of guilt and distress.

Despite his personal turmoil, Haber remained dedicated to scientific advancement. He continued to make significant contributions to chemistry, including his work on hydrogenation reactions, which were crucial for the production of fatty acids and oils used in soap and margarine production.

Throughout his later years, Haber grappled with the ethical implications of his work. He attempted to focus on peaceful applications of his discoveries, emphasizing their importance for societal progress. However, the shadow of his wartime activities persisted, influencing both his professional and personal life.

In 1933, with the rise of the Nazi regime, Haber, who was of Jewish ancestry, found himself in a precarious position. Fearing for his safety and that of his family, he attempted to emigrate to the United States but passed away in Basel, Switzerland, on January 29, 1934, after a series of heart attacks.

His passing marked the end of an era but left behind a rich legacy of scientific innovation mixed with ethical ambiguity. Haber's life and work continue to be subjects of extensive academic and popular interest, offering valuable insights into the dual nature of scientific discovery and its potential impacts on society.

Evaluation and Reflection

Reflecting on Fritz Haber's life, one sees a figure of immense scientific achievement and complexity. His Haber-Bosch process has had a transformative effect on agriculture and industry, impacting billions of people worldwide. But his involvement in chemical warfare brought him profound ethical challenges and personal despair.

Haber's story serves as a cautionary tale about the ethical responsibilities that accompany scientific discoveries. While his contributions to humanity are undeniable, his personal struggles highlight the potential for scientific advancements to have both beneficial and detrimental effects.

The legacy of Fritz Haber today is one of enduring reflection. As we continue to benefit from his chemical innovations, it is essential to also consider the broader implications and ethical questions they pose. Fritz Haber's journey provides a nuanced perspective on the intricate relationship between science and society, urging us to carefully weigh the potential consequences of our technological advancements.

Moral Reflections and Scientific Responsibility

The enduring relevance of Fritz Haber's legacy lies in the broader discussions it sparks about scientific responsibility and morality. As societies increasingly rely on technological advancements, the example of Haber underscores the need for scientists to critically evaluate the potential societal and ethical impacts of their work.

From a contemporary perspective, the Haber-Bosch process stands out not just as a technical triumph but as a case study in the dual-use nature of scientific discoveries. The process has been central to addressing global food security, but it also highlights the risks associated with technologies that have both civilian and military applications. This duality necessitates careful consideration and regulation to ensure that scientific progress aligns with ethical values.

Efforts to address the dual-use challenge have gained momentum since Haber's time. Organizations like the International Council for Science (ICSU) and the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) have developed guidelines and standards to help researchers navigate ethical dilemmas. These initiatives aim to promote responsible research and innovation by fostering open dialogue and international collaboration.

Public engagement and education play critical roles in shaping societal responses to scientific advancements. Initiatives like science communication programs in schools and public forums can help raise awareness about the ethical dimensions of scientific research. By involving the broader public in these discussions, scientists can better understand the concerns and expectations of society, thereby fostering trust and confidence in scientific endeavors.

Moreover, interdisciplinary approaches have become essential in addressing the multidimensional implications of scientific discoveries. Collaboration between ethicists, policymakers, and scientists can help develop frameworks that balance the benefits of technological advancements with the need for ethical considerations. This collaborative framework can guide researchers in making informed decisions that promote both innovation and social welfare.

Another key aspect is the need for transparency and accountability in scientific research. Publishing studies and sharing data openly can help build trust and enable peer review processes to identify potential ethical issues. Institutions and funding agencies can support this openness by implementing policies that reward scientists for responsible conduct of research.

The legacy of Fritz Haber has inspired ongoing debates about the roles and responsibilities of scientists in society. His story serves as a reminder that scientific progress is not just about technical mastery but also about upholding ethical standards. As new technologies emerge, such as genetically modified organisms (GMOs), artificial intelligence, and synthetic biology, the relevance of Haber’s lessons becomes even more pronounced.

In conclusion, Fritz Haber's life and work offer a complex and multifaceted narrative that encapsulates the tensions inherent in scientific advancement. His inventions have had a profoundly positive impact on global food security, yet his involvement in chemical warfare highlights the potential drawbacks of such breakthroughs. Today, as we strive to harness the power of science for the betterment of humanity, it is essential to learn from Haber’s story and approach scientific research with a strong ethical framework. Only through a balanced and responsible approach can we ensure that scientific progress truly benefits society as a whole.

Fritz Haber remains a symbol of scientific ingenuity and moral complexity, reminding us that the quest for knowledge must always be guided by a commitment to ethics and a deep understanding of the human consequences of our actions.

Hermann Staudinger: Pioneering Research in Macromolecular Chemistry

Life and Early Career

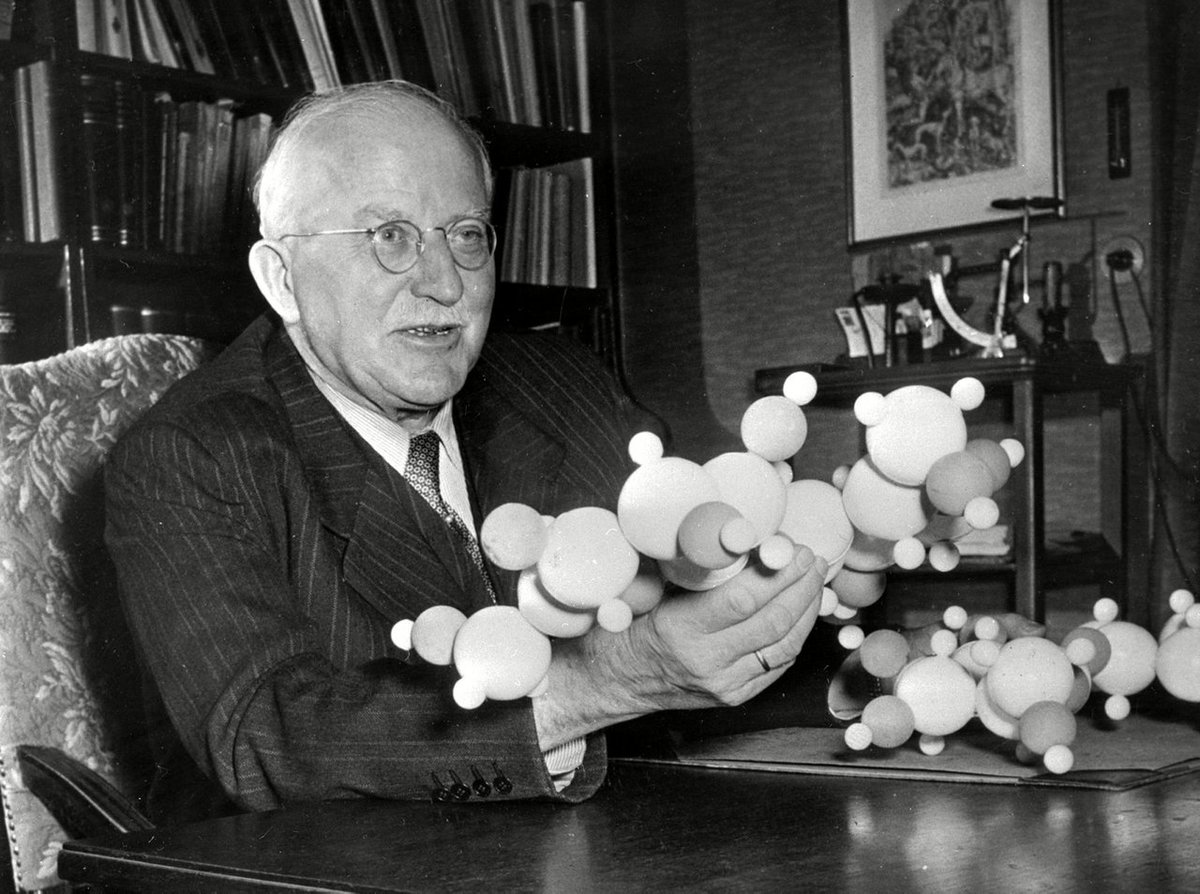

Hermann Staudinger, born on April 19, 1881, in Riezlern, Austria, was a groundbreaking organic chemist who laid the foundations of macromolecular science. His exceptional scientific contributions led to him being awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1953, which he shared with polystyrene pioneer Karl Ziegler. Staudinger's lifelong dedication to the study of large molecules, initially met with skepticism, eventually revolutionized the field of polymer chemistry.

Staudinger grew up in a family deeply rooted in engineering; his father ran a textile plant. This environment instilled in him a practical understanding of technology from an early age, which later proved invaluable in his chemical research. After completing his secondary education, Staudinger enrolled at the University of Innsbruck in 1900 to study chemistry and mathematics. Here, he laid the groundwork for his future academic endeavors.

His studies were not without challenges. At that time, the prevailing belief among chemists was that there was a hard limit to molecule size, known as the high molecular weight problem. Many doubted the existence of long-chain molecules because they lacked the empirical evidence needed to support such theories. Nevertheless, Staudinger believed in the potential of these large molecules and pursued his ideas with unwavering conviction.

In 1905, Staudinger earned his doctorate from the University of Berlin with a dissertation entitled "Studies on Indigo," under the supervision of Emil Fisher, a leading figure in the field of organic chemistry. This experience marked the beginning of his formal training in chemistry. Subsequently, he worked at several universities, including the University of Strasbourg (1907-1914) and the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (1914-1920), where he conducted pioneering research into the behavior of large molecules.

The Concept of Polymers

Staudinger's breakthrough came while he was a professor at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich. In 1920, during a lecture for one of his students, Hans Baeyer, Staudinger suggested that large molecules could be built up from repeated units or monomers. He hypothesized that these macromolecules had a vast array of potential applications, ranging from synthetic polymers like rubber and plastics to more complex materials with unique properties.

This concept was revolutionary because it fundamentally changed how chemists viewed the nature of materials. Prior to Staudinger’s proposal, molecules were considered to be rigid and finite structures, with each atom having a fixed place in a limited-sized chain. Through his research, Staudinger demonstrated that large molecules could exist and possess a wide range of properties due to their extended structure. His work opened up new avenues for the synthesis of novel polymers with specific characteristics tailored for various industrial applications.

To support his theory, Staudinger conducted experiments involving the analysis of macromolecules using ultracentrifuges. These instruments allowed precise measurements of molecular weights, providing irrefutable evidence for the existence of long-chain molecules. Over time, this experimental work solidified the scientific community's understanding of macromolecules.

Staudinger's theoretical framework and experimental techniques paved the way for numerous advancements in polymer chemistry. His hypothesis on macromolecules sparked extensive research into polymerization processes, enabling chemists to develop new methods for synthesizing polymers with desired properties. The discovery had profound implications for industries ranging from manufacturing and construction to healthcare and electronics.

Although the initial reception of Staudinger’s ideas was lukewarm, his persistence and rigorous experimentation ultimately won over even his skeptics. His vision of macromolecules not only revolutionized the field of polymer chemistry but also spurred advancements in related disciplines such as materials science and biochemistry.

Pioneering Contributions

Staudinger's work on macromolecules was far-reaching, encompassing a wide range of topics that expanded our understanding of material science. One area of significant contribution was the development of polymerization reactions. Through careful experimentation, Staudinger elucidated mechanisms for both addition and condensation polymerizations, providing chemists with tools to create polymers with diverse functionalities.

Addition polymerization involves the linkage of monomer units via chemical bonds between double or triple carbon-carbon bonds. Staudinger demonstrated that under appropriate conditions, simple molecules like ethylene could polymerize to form long chains of polyethylene. These findings were crucial for the development of plastic products such as films, bottles, and fibers.

Condensation polymerization, on the other hand, involves reactions where two or more molecules react with the elimination of small molecules like water or methanol. Staudinger's research showed that polyesters and polyamides could be synthesized through this mechanism. These compounds have applications in textiles, coatings, and adhesives.

Staudinger's insights extended beyond just the synthesis of polymers. He also made significant contributions to the understanding of the physical properties of macromolecules. Through his meticulous studies, he discovered that macromolecules could exhibit unique behaviors, such as entanglements and phase transitions, leading to phenomena like elasticity and viscosity.

The application of these discoveries was immense. For instance, the ability to produce synthetic rubber with elasticity similar to natural rubber transformed the tire industry, drastically reducing dependence on natural latex imports. Other industries, including packaging, textiles, and pharmaceuticals, also benefited from the enhanced understanding of polymer behavior.

Staudinger's interdisciplinary approach further distinguished his work. By integrating concepts from physics, engineering, and biology, he created a comprehensive framework for studying polymers. His research bridged gaps between traditional silos of chemistry, leading to more holistic solutions in material design.

Throughout his career, Staudinger maintained a relentless pursuit of knowledge. He collaborated extensively with other scientists and engineers, fostering a collaborative scientific community essential for advancing the field. These collaborations resulted in numerous publications and patents, cementing his legacy as a trailblazer in macromolecular chemistry.

Innovative Experimental Techniques

As Staudinger delved deeper into his research, he developed innovative experimental techniques to validate his hypotheses about macromolecules. One such method involved the use of ultracentrifugation, which allowed him to measure the molecular weights of polymers with unprecedented accuracy. By applying centrifugal forces, these devices could separate macromolecules based on their sizes, providing concrete evidence for their existence.

Another critical technique Staudinger employed was fractionation by solvent extraction. This method involved dissolving polymers in solvents with different polarities and gradually removing them to isolate fractions of varying molecular weights. This procedure helped refine his understanding of polymer structure and confirmed the presence of long-chain molecules.

Staudinger also utilized chromatography to analyze the components of polymers. Chromatographic separation techniques allowed him to identify and quantify the monomer units that comprised the macromolecules, further supporting his theory. These experiments provided tangible proof that large molecules could indeed be constructed from smaller monomers, laying the groundwork for the systematic exploration of polymer chemistry.

Moreover, Staudinger's work on rheology—a field concerned with the flow of deformable materials—was instrumental in understanding the physical properties of macromolecules. Rheological studies involved measuring the viscosity and elasticity of polymer solutions and melts, which revealed the unique behaviors of these molecules under various conditions.

Impact on Industrial Applications

The implications of Staudinger’s discoveries extended far beyond academic settings. They had transformative effects on various industrial processes, particularly in the production of synthetic polymers. One of the most notable outcomes was the creation of synthetic rubbers, which became crucial in World War II due to the disruption of natural rubber supplies from Asia.

During the war, many countries focused on developing synthetic alternatives to natural rubber. American companies like DuPont developed neoprene, a flexible synthetic rubber made from chloroprene, and other companies produced butyl rubber. German companies, influenced by Staudinger's theories, also developed similar materials to meet industrial demands.

Post-war, the development of synthetic polymers continued to boom. Companies worldwide began exploring new forms of polymerization and synthesis methods, leading to the proliferation of plastic products across various industries. Polyethylene, nylon, polyesters, and many other materials became staple commodities that reshaped everyday life.

The advent of plastic bags, disposable containers, and durable industrial components all benefited from Staudinger’s research. These innovations not only enhanced manufacturing efficiency but also provided more sustainable alternatives compared to earlier products. For instance, the development of high-strength fiber-reinforced composites has dramatically improved the performance of aerospace and automotive parts.

Furthermore, Staudinger's work laid the foundation for biocompatible polymers, which are now widely used in medical applications. Bioresorbable sutures, drug delivery systems, and artificial implants have all been developed thanks to the principles established by Staudinger. The field of biomaterials continues to advance, driven by ongoing innovations in polymer science.

Recognition and Legacy

Staudinger's groundbreaking work did not go unnoticed by the scientific community. In recognition of his contributions to chemistry, he received numerous awards and honors throughout his career. Most notably, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1953, alongside Karl Ziegler for their discoveries in the area of high-molecular-weight compounds. This accolade cemented his status as one of the giants in the field of organic chemistry.

Staudinger also held several prestigious positions during his lifetime. In 1920, he became a full professor at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich, where he would spend over three decades conducting groundbreaking research. Later in his career, he accepted a position at the University of Freiburg (1953-1966) and served as its rector from 1956 to 1961. These roles provided him platforms to mentor the next generation of chemists, ensuring that his vision lived on.

The impact of Staudinger's work extends beyond individual recognition. His theories and experiments formed the bedrock upon which an entire field of study was built. Thousands of chemists around the world followed in his footsteps, pushing the boundaries of what was possible with polymers. Today, macromolecular chemistry is a vibrant discipline with applications in areas ranging from nanotechnology to renewable energy.

Staudinger's legacy is not limited to science alone. His dedication to rigorous experimentation and his willingness to challenge prevailing paradigms have inspired countless researchers. His approach to tackling complex problems by combining theoretical insights with practical solutions remains an exemplary model for scientists today.

Awards and Honors

Beyond the Nobel Prize, Staudinger accumulated a substantial list of accolades that underscored his standing in the scientific community. In addition to the Nobel Prize, he received the Max Planck Medal (1952), the Faraday Medal (1955), and the Davy Medal (1962). These awards not only recognized his outstanding contributions but also highlighted his impact on both the theoretical and applied aspects of chemistry.

Staudinger's leadership and mentorship were also widely acknowledged. He played a pivotal role in fostering an environment conducive to innovation, nurturing a culture of inquiry and collaboration. Many of his students went on to make significant strides in their respective fields, carrying forward the torch of macromolecular research.

Staudinger's influence extended to international organizations as well. He was elected a foreign member of the Royal Society (1949) and served as a member of the German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina. These memberships attested to his global reputation in the sciences and underscored his contributions to the advancement of knowledge on a global scale.

Moreover, Staudinger's impact was also felt through his public lectures and writings. Despite his retiring personality, he found ways to communicate complex scientific ideas to a broader audience. His popular scientific writing and public talks helped bridge the gap between academia and society, inspiring both experts and laypeople alike.

Conclusion

Hermann Staudinger's journey from a skeptical environment to becoming a pioneering figure in macromolecular chemistry exemplifies the power of persistent scientific inquiry. His bold hypotheses and rigorous experimental methods paved the way for significant advancements in polymer science, impacting industries across the globe. His legacy continues to inspire chemists and materials scientists, ensuring that the importance of understanding and manipulating large molecules endures.

As we reflect on Staudinger's contributions, it becomes clear that his work represents not just a turning point but an entire era of chemical innovation. His dedication to challenging conventional wisdom and his commitment to evidence-based research laid the foundation for modern polymer chemistry, shaping the world we live in today.

Modern Relevance and Future Directions

Today, the foundational principles established by Staudinger continue to be relevant, driving new discoveries and technological advancements. Polymer science, once seen as a niche field, has become an integral part of contemporary research. Innovations in nanotechnology, biomedicine, and sustainable materials have all been influenced by Staudinger’s initial insights into macromolecular chemistry.

In nanotechnology, the control over molecular structure at the nanoscale has enabled the development of advanced materials with tailored properties. These materials find applications in electronics, where nanofabrication techniques rely heavily on precise manipulation of macromolecules. Similarly, in biotechnology, the integration of polymers into biomedical devices and therapies owes much to the principles pioneered by Staudinger.

The sustainability crisis has also seen the emergence of eco-friendly polymers. Research into biodegradable polymers that can replace conventional plastics is a direct result of the fundamental understanding of macromolecular chemistry. Bioplastics, derived from renewable resources, promise to reduce environmental impacts by providing sustainable alternatives to petrochemical-derived plastics.

Moreover, advances in computational chemistry now allow researchers to simulate and predict the behavior of complex macromolecules. Molecular dynamics simulations and quantum mechanical calculations have become essential tools for designing new polymers and understanding their properties. These techniques, built on the theoretical underpinnings established by Staudinger, are pushing the boundaries of what is achievable in material science.

Applications in Industry

The applications of macromolecular chemistry extend far beyond academic research. Industries such as pharmaceuticals, aerospace, and automotive have leveraged Staudinger’s discoveries to develop cutting-edge products. In the pharmaceutical sector, biodegradable polymers are used in drug delivery systems that control the release of medications over time. These systems can improve therapeutic efficacy and minimize side effects.

In the aerospace and automotive industries, lightweight yet strong materials are crucial for reducing fuel consumption and improving safety. Advanced composite materials, composed of reinforced polymers, offer the required strength-to-weight ratio. Staudinger’s insights into the behavior of macromolecules under stress conditions help engineers design safer and more efficient vehicles.

The textile industry has also benefitted significantly from macromolecular research. The development of smart fabrics that respond to environmental stimuli, such as temperature or moisture, relies on the understanding of macromolecular interactions. These materials are not only functional but also sustainable, offering alternatives to traditional materials that may be harmful to the environment.

Innovation in Sustainable Materials

Sustainability is a key focus area in the development of new polymers. Researchers are increasingly looking to natural and renewable sources for producing biopolymers. Plant-based materials, such as cellulose, starch, and lignin, offer viable alternatives to petrochemical plastics. By optimizing these natural polymers and developing new synthesis methods, scientists aim to create materials that are both eco-friendly and performant.

Innovations in green chemistry are also driven by Staudinger's legacy. The principle of using less toxic and less hazardous substances in the synthesis of polymers is a direct outcome of his emphasis on rigorous experimentation and evidence-based research. Green materials, characterized by minimal waste and recyclability, align with the growing demand for environmentally responsible practices.

Furthermore, the development of new polymers for energy applications is another emerging area. Organic solar cells, for instance, rely on the manipulation of macromolecules to harvest sunlight efficiently. Staudinger's insights into polymer behavior under various conditions inspire new strategies for optimizing these devices, potentially revolutionizing renewable energy solutions.

Conclusion

Hermann Staudinger's contributions to macromolecular chemistry have had a lasting impact on almost every aspect of materials science and technology. From synthetic rubbers and plastics to advanced biodegradable materials and sustainable energy solutions, his foundational work continues to drive innovation and inspire future generations of scientists.

As we stand on the shoulders of his giants, it is evident that the journey of exploring macromolecules is far from over. New challenges continue to emerge, from developing more efficient polymers to addressing the environmental impact of materials. Staudinger's legacy serves as a reminder of the importance of persistent questioning and rigorous investigation in advancing our scientific knowledge.

Through his visionary ideas and relentless pursuit of understanding, Hermann Staudinger has left an immeasurable mark on the field of chemistry. His work not only paved the way for countless applications but also shaped our understanding of the molecular world. As we continue to push the boundaries of what is possible with polymers, we honor his legacy by building upon his foundational discoveries.

The First Law of Thermodynamics: Complete Guide

The First Law of Thermodynamics is a fundamental principle governing energy conservation. It states that the change in a system's internal energy equals the heat added plus the work done on the system. This law serves as the cornerstone for understanding energy transfer in physical and chemical processes.

Fundamental Principles and Modern Developments

This section explains the core concepts and recent advancements related to the First Law. We will explore its mathematical formulation and specific applications in modern science. Understanding these elements is crucial for grasping thermodynamics.

Mathematical Formulation and Energy Balance

The First Law of Thermodynamics is mathematically expressed as δU = δQ + δW. In this equation, U represents the internal energy of the thermodynamic system. The terms Q and W denote the heat transferred and the work done, respectively.

For systems involving volume change, work is often defined as W = -PδV. This specific formulation is essential for analyzing processes in control volumes, such as engines and turbines. The law ensures energy is neither created nor destroyed, only transformed.

Specific Heats and Energy Calculations

The concepts of specific heat at constant volume (Cv) and constant pressure (Cp) are direct derivatives of the First Law. These properties relate changes in internal energy (u) and enthalpy (h) to temperature changes. The equations Cv ≈ du/dT and Cp ≈ dh/dT are fundamental.

Calculating energy changes often involves integrating these specific heats. For example, the change in internal energy between two states is u2 - u1 = ∫ Cv dT. These integrals are vital for practical thermodynamic analysis.

Recent Developments in Chemical Thermodynamics

Modern applications of the First Law have expanded significantly into chemical thermodynamics. Since 2021, it has been integrated into theories of solutions and electrolytes. Pioneers like van 't Hoff, Ostwald, and Arrhenius built their work on this foundation.

Their research established the theory of ionic dissociation and osmotic pressure. Furthermore, statistical mechanics now applies the First Law to non-equilibrium and irreversible processes. This expands its relevance beyond classical, reversible systems.

Essential Historical Context

The historical development of thermodynamics provides critical insight into the First Law's significance. Its evolution is intertwined with the broader understanding of energy conservation. This context highlights its revolutionary impact on science.

The 19th Century and the Conservation of Energy

The First Law was first rigorously applied in thermochemistry during the 19th century. This occurred after scientists fully grasped the principle of energy conservation. Initially, chemists were the primary users, applying it within laboratory settings to understand heat changes in reactions.

At this stage, the Second Law of Thermodynamics, dealing with entropy, had not yet been formally introduced. The foundational work on the First Law set the stage for later physicists like Gibbs, Duhem, and Helmholtz. They would later develop the more complex concepts of entropy and free energy.

Early Applications and Foundational Explanations

The law proved powerful in explaining a wide range of phenomena. Early applications included electrolysis, electrode polarization, and the electrical double layer described by Helmholtz. In chemistry, it directly led to the establishment of thermochemistry as a distinct field.

It also provided the basis for developing theories of ideal and real gases. The famous Van der Waals equation is a key example of applying these principles to account for molecular interactions and finite molecular size in real gases.

The integration of the First Law into early chemical theory fundamentally changed how scientists viewed energy transformation in reactions, paving the way for modern chemical engineering.

Key Concepts and Terminology

Mastering the First Law requires familiarity with its associated terminology. These terms form the language used to describe energy interactions and system properties. A clear understanding is essential for advanced study.

- Internal Energy (U): The total energy contained within a system, encompassing kinetic and potential energy at the molecular level.

- Heat (Q): Energy transferred between a system and its surroundings due to a temperature difference.

- Work (W): Energy transferred by a force acting through a distance, such as expansion or compression work (often -PδV).

- Enthalpy (H): A property defined as H = U + PV, particularly useful for constant-pressure processes.

- Specific Heat (Cv, Cp): The amount of heat required to raise the temperature of a unit mass by one degree under constant volume or pressure.

These concepts are not isolated; they are interconnected through the First Law. For instance, the definition of enthalpy makes it exceptionally useful for analyzing flow processes and chemical reactions occurring at constant pressure, which are common in engineering applications.

Fundamental Gas Laws and Relationships

The behavior of ideal gases provides a straightforward application of thermodynamic principles. Several key gas laws, which are consistent with the First Law, describe these relationships. The following table summarizes the most critical ones.

| Law | Relationship | Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Boyle's Law | P ∝ 1/V | Constant Temperature (Isothermal) |

| Charles's Law | V ∝ T | Constant Pressure (Isobaric) |

| Avogadro's Law | V ∝ n | Constant Temperature & Pressure |

| Van der Waals Equation | (P + a/Vm2)(Vm - b) = RT | Corrects for molecular interactions and volume in real gases |

These laws collectively lead to the Ideal Gas Law (PV = nRT), a cornerstone equation in thermodynamics. The Van der Waals equation introduces corrections for real gas behavior, making it a more accurate model for many practical situations. Understanding these relationships is a direct application of the energy principles embedded in the First Law.

Modern Applications in Engineering Curricula

The First Law of Thermodynamics remains a cornerstone of engineering education. It is integrated into undergraduate and graduate programs for mechanical and chemical engineers. Modern courses emphasize energy analysis within control volumes and the behavior of real gases.

These applications are critical for designing efficient systems like turbines, compressors, and reactors. The fundamental equation δU = δQ + δW serves as the starting point for more complex analyses. Mastering this principle is essential for any career in energy systems or process engineering.

Control Volume Analysis for Flow Processes

Engineering applications frequently involve systems where mass flows across boundaries. This requires shifting from a closed system analysis to an open system or control volume approach. The First Law is reformulated to account for the energy carried by mass entering and exiting the system.

This leads to the concept of enthalpy (H = U + PV), which becomes the primary property of interest for flowing streams. Analyzing devices like nozzles, diffusers, and heat exchangers relies heavily on this control volume formulation. It provides a powerful tool for calculating work output, heat transfer, and overall system efficiency.

The ability to apply the First Law to control volumes is what separates thermodynamic theory from practical engineering design, enabling the calculation of performance for real-world equipment.

Real Gas Behavior and Equation of State

While the ideal gas law is a useful approximation, many engineering applications involve conditions where real gas effects are significant. The Van der Waals equation and other more complex equations of state correct for intermolecular forces and finite molecular volume.

Understanding these deviations is crucial for accurate calculations in high-pressure or low-temperature environments. The First Law provides the framework into which these real gas properties are inserted. This ensures energy balances remain accurate even when ideal gas assumptions break down.

- Compressibility Factor (Z): A multiplier used to correct the ideal gas law for real gas behavior (PV = ZRT).

- Principle of Corresponding States: Suggests that all gases behave similarly when compared at the same reduced temperature and pressure.

- Fugacity: A corrected "effective pressure" that replaces pressure in thermodynamic calculations for real gases.

Current Trends and Statistical Mechanics

The application of the First Law has expanded beyond classical thermodynamics into modern physics. It is now deeply integrated with statistical thermodynamics, which provides a molecular-level perspective. This branch connects macroscopic properties to the behavior of countless individual molecules.

Statistical mechanics applies the First Law to non-equilibrium states and irreversible processes. This is a significant advancement, as classical thermodynamics primarily focused on equilibrium and reversible paths. The focus has shifted towards understanding the extensivity of properties like entropy and free energy.

Integration with Gibbs-Duhem and Gibbs-Helmholtz Equations

The First Law is not an isolated principle but part of a interconnected web of thermodynamic relationships. It forms the foundation for more advanced concepts like the Gibbs-Duhem equation, which relates changes in chemical potential for mixtures.

Similarly, the Gibbs-Helmholtz equation connects enthalpy and Gibbs free energy, which is crucial for predicting the temperature dependence of chemical reactions and phase equilibria. Mastering these interrelated equations is key for advanced work in materials science and chemical engineering.

These relationships also introduce critical concepts like chemical potential, fugacity, and activity. These terms allow thermodynamicists to quantitatively describe the behavior of components in mixtures, which is essential for designing separation processes and understanding chemical reaction equilibria.

Emerging Applications in Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics

One of the most exciting modern trends is the application of thermodynamic principles to systems far from equilibrium. This includes biological systems, nanotechnology, and complex materials. The First Law provides the essential energy accounting framework even when systems are evolving dynamically.

Research in this area seeks to understand how energy is transformed and transported in these complex environments. The goal is to extend the predictive power of thermodynamics beyond its traditional boundaries. This work has profound implications for developing new technologies and understanding biological energy conversion.

- Biological Energy Conversion: Analyzing metabolic pathways and ATP synthesis using thermodynamic principles.

- Materials Science: Designing new materials with specific thermal properties for energy storage and conversion.

- Environmental Engineering: Modeling heat and mass transfer in atmospheric and oceanic systems to understand climate dynamics.

Practical Implications and Problem-Solving Strategies

Successfully applying the First Law requires a systematic approach to problem-solving. Engineers and scientists must be adept at defining the system, identifying interactions, and applying the correct form of the energy balance. This practical skill is developed through extensive problem-solving practice.

The choice of system boundary—whether closed or open—dictates the specific form of the First Law equation used. Clearly identifying all heat and work interactions across this boundary is the most critical step. Omission of a single energy transfer term is a common source of error.

Step-by-Step Application Methodology

A reliable methodology ensures accurate application of the First Law across diverse scenarios. The following steps provide a robust framework for tackling thermodynamic problems systematically.

- Define the System: Clearly state what is included within your system boundary and whether it is a closed or control volume.

- Identify Initial and Final States: Determine the properties (P, V, T, etc.) at the beginning and end of the process.

- List All Energy Interactions: Account for every heat transfer (Q) and work (W) interaction crossing the boundary.

- Apply the Appropriate First Law Form: Write the equation ΔU = Q + W (closed) or the more complex energy rate balance for control volumes.

- Utilize Property Relations: Incorporate equations of state and property data (e.g., using steam tables or ideal gas relations) to solve for unknowns.

Adhering to this structured approach minimizes errors and builds a strong conceptual understanding. It transforms the First Law from an abstract equation into a powerful analytical tool.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Even experienced practitioners can encounter pitfalls when applying the First Law. Awareness of these common mistakes is the first step toward avoiding them. One major error involves incorrectly specifying the sign convention for heat and work.

Another frequent mistake is failing to account for all forms of work, especially subtle ones like shaft work or electrical work. Assuming constant specific heats when temperature changes are large can also lead to significant inaccuracies. Careful attention to detail and consistent use of a sign convention are essential for reliable results.

A deep understanding of the First Law's sign conventions—heat added to a system is positive, work done on a system is positive—is more important than memorizing equations for success in thermodynamic analysis.

The Relationship to Advanced Thermodynamic Concepts

The profound power of the First Law is unlocked when it is combined with the Second Law. Together, they form the complete framework for classical thermodynamics. The First Law concerns the quantity of energy, while the Second Law governs its quality and direction of processes.

This relationship gives rise to derived properties of immense importance. The combined laws lead directly to the definitions of Helmholtz Free Energy (A) and Gibbs Free Energy (G). These concepts are indispensable for predicting the spontaneity of chemical reactions and phase changes.

Entropy and the Combined Law Formulation

When the First Law (δU = δQ + δW) is merged with the definition of entropy (δS ≥ δQ/T), a more powerful combined statement emerges. For reversible processes, this is often written as dU = TdS - PdV. This formulation elegantly links all the fundamental thermodynamic properties.

It demonstrates that internal energy (U) is a natural function of entropy (S) and volume (V). This perspective is central to the development of thermodynamic potentials. These potentials are the workhorses for solving complex equilibrium problems in chemistry and engineering.

- Enthalpy (H=U+PV): Natural variables are entropy (S) and pressure (P); useful for constant-pressure processes.

- Helmholtz Free Energy (A=U-TS): Natural variables are temperature (T) and volume (V); useful for constant-volume systems.

- Gibbs Free Energy (G=H-TS): Natural variables are temperature (T) and pressure (P); most widely used for chemical/physical equilibria.

The combined First and Second Law formulation is the master equation from which nearly all equilibrium thermodynamic relations can be derived, making it the single most important tool for theoretical analysis.

Chemical Potential, Fugacity, and Activity

Extending the First Law to multi-component systems introduces the concept of chemical potential (μ). It is defined as the change in internal energy (or another potential) upon adding a particle, holding all else constant. The First Law for open systems must include a Σμidni term.

For real mixtures, the chemical potential is expressed using fugacity (for gases) or activity (for liquids and solids). These are "effective" concentrations that correct for non-ideal interactions. They allow the straightforward application of ideal-solution-based equations to complex, real-world mixtures.

This framework is essential for designing separation units like distillation columns and absorption towers. It also allows engineers to predict the equilibrium yield of chemical reactions in industrial reactors. Without the foundational energy accounting of the First Law, none of these advanced concepts would be possible.

Future Trajectories and Research Frontiers

The First Law of Thermodynamics continues to evolve and find new applications. Current research is pushing its boundaries in several exciting directions. These frontiers aim to address challenges in energy, sustainability, and complex systems science.

Researchers are developing more sophisticated equations of state that apply the First Law's energy balance with greater accuracy. They are also integrating thermodynamics with machine learning models to predict material properties. This synergy between fundamental law and modern computation is opening new avenues for discovery.

Non-Equilibrium Systems and Extended Frameworks

A major thrust in modern physics is the development of thermodynamics for systems persistently far from equilibrium. Classical equilibrium thermodynamics, while powerful, has limits. Researchers are formulating extended thermodynamic theories that retain the First Law's conservation principle.

These theories incorporate internal variables and rate equations to describe how systems evolve. Applications range from understanding the thermodynamics of living cells to modeling the behavior of complex fluids and soft matter. The core principle—that energy is conserved—remains inviolate, even as the mathematical framework grows more complex.

Energy Systems and Sustainability

In the face of global climate challenges, the First Law has never been more practically relevant. It is the fundamental tool for analyzing the efficiency and performance of all energy conversion technologies. Every advancement in renewable energy—from advanced photovoltaics to next-generation batteries—relies on rigorous First Law analysis.

- Energy Storage: Evaluating the round-trip efficiency of batteries, flywheels, and pumped hydro storage.

- Carbon Capture: Calculating the energy penalties associated with separating CO2 from flue gases or the atmosphere.

- Fuel Cells and Electrolyzers: Performing energy balances to optimize hydrogen production and utilization.

- Waste Heat Recovery: Applying First Law analysis to Rankine cycles and thermoelectric generators to reclaim lost energy.

Optimizing these systems for maximum efficiency directly contributes to reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The First Law provides the quantitative metrics needed to guide technological development and policy.

Conclusion and Final Key Takeaways

The First Law of Thermodynamics is far more than a historical scientific principle. It is a living, essential framework that underpins modern science and engineering. From its elegant mathematical statement δU = δQ + δW springs the ability to analyze, design, and optimize nearly every energy-related technology on the planet.

Its journey from 19th-century thermochemistry to the heart of statistical mechanics and non-equilibrium theory demonstrates its enduring power. The law’s integration with concepts like enthalpy, free energy, and chemical potential has created a rich and indispensable body of knowledge. Mastery of this concept is non-negotiable for professionals in a wide array of fields.

Essential Summary of Core Principles

To conclude, let's revisit the most critical points that define the First Law of Thermodynamics and its application.

- Energy Conservation is Absolute: Energy cannot be created or destroyed, only converted from one form to another. The total energy of an isolated system is constant.

- It Defines Internal Energy: The law quantifies internal energy (U) as a state function. The change in U depends only on the initial and final states, not the path taken.

- It Accounts for All Interactions: Any change in a system's internal energy is precisely accounted for by the net heat transferred into the system and the net work done on the system.

- It is the Foundation for Other Concepts: Enthalpy (H), specific heats (Cv, Cp), and the analysis of control volumes are all derived from the First Law.

- It is Universal and Unifying: The law applies equally to ideal gases, real gases, liquids, solids, chemical reactions, and biological systems. It provides a common language for energy analysis across all scientific disciplines.

Understanding these principles provides a powerful lens through which to view the physical world. It enables one to deconstruct complex processes into fundamental energy transactions.

A Foundational Tool for the Future

As we confront global challenges in energy, environment, and advanced technology, the First Law’s importance will only grow. It is the bedrock upon which sustainable solutions are built. Engineers will use it to design more efficient power grids and industrial processes.

Scientists will continue to rely on it as they explore the thermodynamics of quantum systems and novel materials. The principle of energy conservation remains one of the most well-tested and reliable concepts in all of science. Its continued application promises to drive innovation for generations to come.