Charles Friedel : Pionnier de la Chimie Organique Française

Charles Friedel demeure une figure majeure de la chimie du XIXe siècle, un savant dont l'héritage scientifique transcende les époques. Considéré comme un véritable pionnier de la chimie organique en France, son nom reste indissociable d'une avancée fondamentale : la fameuse réaction de Friedel-Crafts. Cette découverte, fruit d'une collaboration fructueuse et même d'un heureux hasard, a révolutionné la synthèse des composés aromatiques.

Son oeuvre, qui s'étend de la minéralogie à la chimie organique, continue d'inspirer les chimistes d'aujourd'hui. Bien que l'avancement de la chimie en Amérique du Nord ne soit pas directement son fait, son influence est universelle. Son travail sur les dérivés du silicium et les réactions de substitution aromatique constitue un pilier intemporel de la recherche et de l'industrie chimique moderne. Cet article retrace le parcours de cet illustre chimiste français.

La Formation d'un Esprit Brillant à Strasbourg et Paris

Charles Friedel voit le jour le 12 mars 1832 à Strasbourg. Dans une Europe en pleine mutation scientifique, il reçoit une éducation qui l'oriente naturellement vers les sciences. Sa curiosité naturelle et son intelligence aiguë le mènent rapidement vers les plus prestigieuses institutions parisiennes, celles-là même où se forgent les grands esprits de l'époque.

Sous l'Aile de Louis Pasteur à la Sorbonne

La carrière académique de Friedel prend un tournant décisif lorsqu'il intègre la Sorbonne. Il a la chance d'y suivre les enseignements de maîtres illustres, dont le célèbre Louis Pasteur. Ce dernier, déjà renommé pour ses travaux sur la chiralité moléculaire, influence sans doute la rigueur et la précision expérimentale qui caractériseront toujours Friedel.

Friedel soutient sa thèse de doctorat en 1869, après des années de recherches approfondies. Ce travail fondateur porte sur l'étude des cétones et des aldéhydes, mais aussi sur un sujet a priori éloigné : la pyroélectricité des cristaux. Cette dualité thématique annonce déjà la carrière atypique d'un homme qui refusera de s'enfermer dans une seule discipline.

Un Début de Carrière entre Minéraux et Molécules

Avant même son doctorat, Charles Friedel commence sa vie professionnelle au sein de l'École des Mines de Paris. Il y occupe le poste de conservateur des collections de minéralogie dès 1856. Ce rôle lui permet d'acquérir une connaissance intime de la structure et des propriétés des minéraux.

Cette immersion dans le monde de la minéralogie n'est pas une simple parenthèse. Elle façonne sa vision de la matière et lui apporte une compréhension profonde des structures cristallines. Cette expertise se révélera précieuse plus tard, lorsqu'il explorera les analogies entre les composés du carbone et du silicium. Il est un acteur clé de la fondation de la Société Chimique de France en 1857, qu'il présidera à quatre reprises.

La Prodigieuse Éclosion d'une Carrière Scientifique

À partir des années 1870, la carrière de Charles Friedel s'accélère et atteint des sommets institutionnels. Ses premières découvertes en chimie organique le propulsent sur le devant de la scène académique française. Il devient progressivement l'un des piliers de l'enseignement supérieur scientifique à Paris, cumulant les reconnaissances et les postes de haute responsabilité.

Du Professorat à la Création d'une École

La reconnaissance de ses pairs l'amène à occuper plusieurs chaires prestigieuses. Il devient professeur à l'École Normale Supérieure en 1871, puis à la Sorbonne en 1876, où il enseigne d'abord la minéralogie. Sa passion pour la chimie des composés carbonés le rattrape, et en 1884, il prend la chaire de chimie organique à la Sorbonne.

Mais son ambition va au-delà de l'enseignement. Désireux de structurer la formation des ingénieurs chimistes, il fonde en 1896 l'Institut de Chimie de Paris. Cette institution, née de sa vision, deviendra plus tard la prestigieuse École de Chimie de Paris, connue aujourd'hui sous le nom de Chimie ParisTech - PSL. Cet héritage éducatif est l'un de ses plus grands accomplissements.

Premières Découvertes en Synthèse Organique

Avant la découverte qui immortalisera son nom, Friedel signe déjà des réussites scientifiques notables. Avec James Mason Crafts, son collaborateur américain, il réalise plusieurs synthèses importantes qui démontrent sa maîtrise des transformations moléculaires.

- Synthèse de l'alcool isopropylique : Friedel et Crafts réussissent la synthèse de ce qui est considéré comme le premier alcool secondaire obtenu artificiellement.

- Synthèse de la glycérine : En 1871, ils parviennent à produire de la glycérine à partir de dérivés chlorés, une avancée significative.

- Synthèse de l'acide lactique : Ils explorent aussi la voie de production de cet acide organique important en biochimie.

Ces travaux précurseurs témoignent de leur virtuosité expérimentale et préparent le terrain pour la découverte majeure à venir. Leur exploration des composés organiques du silicium ouvre carrément un nouveau champ de recherche, celui de la chimie organo-silicée.

La Rencontre Fondatrice avec James Mason Crafts

L'histoire de la chimie doit beaucoup aux rencontres fortuites et aux collaborations fécondes. Celle entre Charles Friedel et l'Américain James Mason Crafts en est un parfait exemple. Cette alliance transatlantique, rare pour l'époque, va donner naissance à l'un des outils les plus utiles de la synthèse organique moderne.

Le jeune chimiste américain James Mason Crafts arrive à Paris en 1861 pour parfaire sa formation. Il rejoint le laboratoire de Charles Friedel, attiré par la réputation du savant français. Une amitié scientifique naît rapidement entre les deux hommes, fondée sur une curiosité mutuelle et une complémentarité évidente.

Cette collaboration, qui s'étendra de 1874 à 1891, est particulièrement dédiée à l'étude des composés du silicium. C'est en cherchant à comprendre les analogies entre le carbone et le silicium que se produira l'accident heureux menant à leur découverte la plus célèbre.

Les Bases d'une Collaboration Historique

Friedel apporte à cette collaboration sa vaste culture scientifique, sa connaissance intime de la minéralogie et sa position académique établie. Crafts, lui, incarne un esprit pragmatique et novateur, formé dans le contexte dynamique de la science américaine émergente. Ensemble, ils forment une équipe redoutablement efficace.

Leur objectif initial est d'étudier la chimie du silicium, en s'inspirant des travaux de grands chimistes français comme Charles-Adolphe Wurtz et Jean-Baptiste Dumas. Ils tentent de transposer au silicium les réactions connues pour le carbone. C'est dans ce contexte exploratoire que la fortune sourit aux audacieux. En manipulant du chlorure d'aluminium sur un dérivé chloré, ils observent un dégagement inattendu d'acide chlorhydrique et la formation d'hydrocarbures.

L'Accident Heureux : À l'Origine de la Découverte

La genèse de la réaction de Friedel-Crafts est un magnifique exemple de sérendipité en science. Les deux chercheurs ne cherchaient pas, à l'origine, à créer une nouvelle méthode de synthèse. Leur observation minutieuse d'un phénomène inattendu allait pourtant changer le cours de la chimie organique.

En 1877, alors qu'ils étudiaient l'action des chlorures métalliques sur des composés organochlorés, Friedel et Crafts notent un comportement étrange. Lors de leurs expériences avec du chlorure d'aluminium, un puissant acide de Lewis, une réaction vigoureuse se produit avec des hydrocarbures chlorés en présence de benzène. Le résultat est la formation inattendue de nouveaux hydrocarbures alkylés.

Le Mécanisme d'une Découverte Révolutionnaire

Ils comprennent rapidement l'importance de leur observation. Le chlorure d'aluminium agit comme un catalyseur puissant. Il permet de greffer des chaînes carbonées (un groupe alkyle) sur un noyau benzénique à partir d'un halogénure d'alkyle. La réaction, qu'ils nomment alkylation, libère de l'acide chlorhydrique comme sous-produit.

Peu de temps après, ils découvrent une variante tout aussi importante : l'acylation. Dans cette version, un halogénure d'acyle (comme le chlorure de benzoyle) réagit avec un composé aromatique pour former une cétone aromatique. Ces deux réactions - alkylation et acylation - constituent le coeur de ce que le monde scientifique nommera désormais la réaction de Friedel-Crafts.

Ils publieront pas moins de 9 articles de 1877 à 1881 pour détailler les mécanismes, les substrats compatibles et les applications potentielles de leur découverte. Leur travail est si fondamental qu'il leur vaut la prestigieuse médaille Davy en 1880, décernée par la Royal Society de Londres.

Le Mécanisme et l'Impact de la Réaction Friedel-Crafts

La découverte de Friedel et Crafts n'était pas qu'une simple observation. Ils en ont rapidement élucidé le mécanisme fondamental, ce qui a permis son exploitation systématique. La réaction Friedel-Crafts fonctionne grâce au pouvoir catalytique unique des acides de Lewis, comme le chlorure d'aluminium (AlCl3). Ce catalyseur polarise la liaison carbone-halogène du réactif, créant une espèce électrophile puissante.

Cette espèce électrophile attaque alors le nuage d'électrons π riche du noyau aromatique, comme le benzène. Il en résulte la formation d'un carbocation intermédiaire qui se stabilise en perdant un proton. Le processus régénère le catalyseur et conduit au produit alkylé ou acylé souhaité. Cette séquence élégante a ouvert la voie à la synthèse d'une myriade de composés complexes.

Les Deux Piliers : Alkylation et Acylation

La réaction se décline en deux grandes catégories, chacune ayant des applications spécifiques. L'alkylation de Friedel-Crafts permet de greffer une chaîne alkyle sur un cycle aromatique. Par exemple, la réaction du benzène avec du chlorométhane (CH3-Cl) en présence de AlCl3 produit du toluène (C6H5CH3).

- Avantage : Construction rapide de squelettes carbonés complexes.

- Limitation : Risque de sur-alkylation (greffage de plusieurs groupes) et de réarrangements des carbocations.

L'acylation de Friedel-Crafts, quant à elle, conduit à la formation de cétones aromatiques. En utilisant un chlorure d'acyle (R-CO-Cl), on obtient une aryl cétone. Cette variante est souvent préférée car elle n'est pas sujette aux réarrangements et ne conduit généralement qu'à la mono-acylation. Ces deux procédés sont complémentaires et indispensables dans la boîte à outils du chimiste organique.

Applications Industrielles : Du Laboratoire à l'Échelle Planétaire

Le passage de la découverte académique à l'application industrielle a été remarquablement rapide. La réaction Friedel-Crafts a trouvé des débouchés cruciaux dans des secteurs qui allaient façonner le monde moderne. Son impact sur l'industrie chimique est difficile à surestimer, avec des applications allant de la parfumerie à la pétrochimie lourde.

Dès le début du XXe siècle, la réaction est intégrée dans les procédés de raffinage du pétrole pour le craquage des hydrocarbures, améliorant le rendement en carburants. Elle est également centrale dans la production de polymères et de résines.

La Révolution des Colorants et des Produits Pharmaceutiques

L'industrie des colorants synthétiques a été l'une des premières à adopter massivement cette technologie. La synthèse de colorants azoïques et triarylméthanes, aux teintes vives et stables, a reposé sur des étapes clés de type Friedel-Crafts. Cela a permis de démocratiser des couleurs autrefois rares et coûteuses.

Dans le domaine pharmaceutique, la réaction a permis la construction de molécules actives complexes. De nombreux principes actifs, notamment des anti-inflammatoires, des antihistaminiques et des composés antitumoraux, incorporent des motifs synthétisés via cette méthode. Sa capacité à former des liaisons carbone-carbone de manière fiable en fait un pilier de la synthèse organique moderne.

L'Héritage dans la Pétrochimie et les Polymères

L'application la plus massive, en termes de volumes traités, se situe dans la pétrochimie. La réaction est utilisée dans la production d'additifs pour carburants, d'alkylbenzènes linéaires pour détergents, et dans diverses étapes de modification des coupes pétrolières. Elle contribue à optimiser l'utilisation des ressources fossiles.

- Production d'éthylbenzène : Précurseur du styrène, lui-même monomère du polystyrène.

- Synthèse du cumène : Intermédiaire clé pour la production de phénol et d'acétone (procédé au cumène).

- Fabrication de détergents : Alkylation du benzène avec des oléfines à longue chaîne.

Cette omniprésence industrielle témoigne du génie pratique derrière la découverte de Friedel et Crafts. Elle a fonctionné à l'échelle du laboratoire et a pu être transposée avec succès à l'échelle de la tonne, un défi que toutes les réactions académiques ne peuvent relever.

Charles Friedel, Minéralogiste et Visionnaire de la Chimie du Silicium

Si la réaction qui porte son nom a éclipsé ses autres travaux, il serait réducteur de résumer Charles Friedel à cette seule contribution. Tout au long de sa carrière, il a mené de front une passion pour la minéralogie et une recherche novatrice en chimie, en particulier sur les composés organosiliciés. Cette dualité fait de lui un savant complet.

Ses études minéralogiques étaient profondes et reconnues. Il a décrit et caractérisé de nouveaux minéraux, dont la wurtzite, un sulfure de zinc. Ses travaux sur la pyroélectricité des cristaux, initiés lors de son doctorat, ont fait autorité. Il s'est même intéressé à la synthèse de diamants, une entrevision visionnaire qui préfigurait la minéralogie synthétique moderne.

Un Pionnier de la Chimie Organométallique et des Silicones

Sa collaboration avec Crafts a généré des avancées majeures bien avant leur découverte fameuse. Ensemble, ils ont été parmi les premiers à explorer méthodiquement la chimie des composés contenant une liaison carbone-silicium. Ils ont synthétisé une série de tétraalkylsilanes et étudié leurs propriétés.

Ces recherches fondatrices ont posé les bases de ce qui deviendra bien plus tard l'industrie des silicones. Les polymères silicones, aux propriétés uniques de stabilité thermique et d'inertie chimique, sont aujourd'hui omniprésents, des joints d'étanchéité aux implants médicaux. Friedel, sans le savoir, a contribué à jeter les bases de ce domaine.

Reconnaissance et Postérité d'un Géant de la Science

L'œuvre de Charles Friedel a été saluée par ses contemporains et continue d'être honorée. Les récompenses et les postes prestigieux qu'il a occupés témoignent de l'estime dans laquelle le tenait la communauté scientifique internationale. Son héritage institutionnel, à travers l'école qu'il a fondée, perpétue son influence.

Outre la médaille Davy reçue avec Crafts en 1880, Friedel a été décoré de la Légion d'Honneur. Il a été élu membre de l'Académie des sciences et a présidé à plusieurs reprises la Société Chimique de France. Son collaborateur Crafts a, quant à lui, reçu un LL.D. honorifique de l'Université Harvard en 1898, soulignant l'impact transatlantique de leurs travaux.

Un Héritage Familial et Institutionnel Pérenne

La passion pour la science s'est transmise dans sa famille. Son fils, Georges Friedel, est devenu un cristallographe renommé, développant les lois de Friedel en cristallographie géométrique. Cette lignée scientifique illustre l'empreinte durable de Charles Friedel.

L'institution qu'il a créée, l'Institut de Chimie de Paris, a traversé les décennies. Devenue Chimie ParisTech, elle forme encore aujourd'hui les ingénieurs chimistes d'élite de la France. En 2023, Chimie ParisTech et l'Université PSL ont lancé les célébrations du bicentenaire de sa naissance (1832-2032), affirmant la modernité de son héritage.

Aucune statistique récente unique ne résume son impact, mais un indicateur parle de lui-même : la réaction Friedel-Crafts est citée et utilisée dans des milliers de publications scientifiques annuelles. Elle reste un sujet de recherche actif, avec des chercheurs développant des variantes plus vertes et plus sélectives.

La longévité et la vitalité de cette réaction sont le plus bel hommage à Charles Friedel. D'un accident de laboratoire est né un outil fondamental qui a permis d'explorer et de construire une part immense du paysage moléculaire du monde moderne. Son histoire rappelle que la science progès souvent par des chemins inattendus, guidée par la curiosité et l'observation rigoureuse.

La Réaction Friedel-Crafts à l'Ère de la Chimie Verte

Au XXIe siècle, la quête de processus chimiques plus durables a conduit à réinventer les méthodes classiques. La réaction Friedel-Crafts, bien que d'une efficacité prouvée, n'échappe pas à cette évolution. Les catalyseurs traditionnels comme le chlorure d'aluminium sont corrosifs, difficiles à manipuler et génèrent de grands volumes de déchets acides. La recherche moderne se concentre donc sur le développement de catalyseurs verts et réutilisables.

Les scientifiques explorent aujourd'hui une variété d'alternatives. Les catalyseurs à base d'acides solides, comme les zéolites modifiées ou les argiles pillarisées, offrent une excellente sélectivité et sont faciles à séparer du milieu réactionnel. Les liquides ioniques, avec leur pression de vapeur négligeable, servent à la fois de solvant et de catalyseur, réduisant l'impact environnemental.

Vers une Catalyse Plus Durable et Sélective

L'objectif est de conserver la puissance de la transformation tout en minimisant son empreinte écologique. Les progrès dans le domaine de la catalyse hétérogène et de la catalyse par acides de Lewis activés sont particulièrement prometteurs. Ces nouvelles versions « vertes » de la réaction répondent aux principes de la chimie durable tout en élargissant son champ d'application.

- Catalyseurs biodégradables : Développement de systèmes catalytiques à base de biopolymères ou de dérivés naturels.

- Activation par micro-ondes : Réduction drastique des temps de réaction et de la consommation d'énergie.

- Procédés sans solvant : Réalisation des réactions en milieu néat ou avec des réactifs supports, éliminant les solvants organiques volatils.

Ces innovations montrent que la réaction découverte par Friedel et Crafts n'est pas une relique du passé. Elle est un outil vivant et évolutif, constamment remodelé pour répondre aux défis scientifiques et environnementaux contemporains.

Dépasser les Limites : Les Avancées Contemporaines

La réaction classique présentait certaines limitations, comme la sensibilité des substrats aux acides forts ou la difficulté à alkyler des noyaux aromatiques désactivés. La recherche fondamentale des dernières décennies a permis de contourner ces obstacles. L'utilisation de catalyseurs à base de métaux de transition (palladium, cuivre, fer) a ouvert la voie à des mécanismes radicalement différents.

Ces variantes catalysées par métaux de transition permettent d'activer des liaisons C-H peu réactives, évitant ainsi l'utilisation préalable de groupements fonctionnels halogénés. Cette approche, plus directe et générant moins de sous-produits, représente un saut conceptuel majeur. Elle étend considérablement la palette des substrats compatibles.

Ces développements récents illustrent comment un outil centenaire peut être le point de départ de nouvelles branches de la chimie. Ils renforcent le statut de la réaction Friedel-Crafts comme réaction fondamentale, dont les principes continuent d'inspirer des découvertes.

L'Impact sur la Synthèse de Molécules Complexes

La capacité à fonctionnaliser des noyaux aromatiques de manière fiable est cruciale en recherche pharmaceutique et en science des matériaux. Les versions modernes de la réaction sont employées pour construire des architectures moléculaires sophistiquées, comme des ligands pour la catalyse ou des cadres organométalliques poreux (MOFs).

En synthèse totale de produits naturels complexes, les étapes de type Friedel-Crafts, souvent asymétriques et catalysées par un organocatalyseur, permettent d'établir des centres stéréogéniques avec un haut degré de contrôle. Cette évolution d'une réaction brute vers un outil de synthèse stéréosélective est un témoignage de sa maturité et de sa polyvalence.

L'Héritage Intellectuel et la Vision d'un Savant Complet

Au-delà de la découverte technique, Charles Friedel a laissé un héritage intellectuel profond. Son parcours démontre l'importance de l'interdisciplinarité. En refusant de cloisonner la minéralogie et la chimie organique, il a favorisé des connexions fécondes entre des domaines a priori éloignés. Sa vision holistique de la science des matériaux était en avance sur son temps.

Il était aussi un bâtisseur d'institutions et un éducateur dévoué. En fondant l'Institut de Chimie de Paris, il a voulu créer un lieu où la théorie et la pratique industrielle se rencontrent. Cette philosophie pédagogique, centrée sur l'expérimentation et l'application, a influencé des générations d'ingénieurs et de chercheurs.

Friedel et la Tradition Scientifique Française

Charles Friedel s'inscrit dans la grande tradition de la chimie française du XIXe siècle, aux côtés de figures comme Pasteur, Wurtz et Dumas. Il a contribué à maintenir le rayonnement international de cette école de pensée. Sa capacité à attirer et à collaborer avec un talent étranger comme James Crafts montre son ouverture et son influence.

Son travail sur les analogies carbone-silicium s'inscrit directement dans les réflexions de l'époque sur la tétravalence et la périodicité des éléments. En explorant systématiquement la chimie du silicium, il a validé expérimentalement des concepts théoriques émergents et a ouvert la voie à un domaine chimique entier.

Conclusion : L'Immortalité d'une Découverte Fondamentale

Le parcours de Charles Friedel est celui d'un savant dont la contribution a profondément et durablement marqué la science. De ses débuts en minéralogie à ses travaux pionniers en chimie organique, son œuvre illustre la puissance d'un esprit curieux et rigoureux. La réaction Friedel-Crafts reste son monument le plus visible, une réaction qui, près de 150 ans après sa découverte, demeure incontournable.

Cette longévité exceptionnelle s'explique par son utilité fondamentale : elle permet de construire les liaisons carbone-carbone qui sont le squelette de la matière organique. Des laboratoires de recherche académique aux plus grands complexes pétrochimiques du monde, son empreinte est partout. Elle est un pilier de la synthèse organique, ayant permis la création d'innombrables molécules aux propriétés variées.

Les Clés d'un Héritage Durable

- Universalité : Un mécanisme applicable à une vaste gamme de substrats et de réactifs.

- Robustesse : Une réaction fiable, capable de passer du microgramme à la tonne industrielle.

- Évolutivité : Une capacité à inspirer des améliorations et des variantes modernes, notamment en chimie verte.

- Pédagogie : Un exemple classique enseigné dans toutes les facultés de chimie du monde, formant l'esprit des futurs scientifiques.

Charles Friedel n'était pas un pionnier de la chimie en Amérique du Nord, mais un géant de la science française dont l'influence est véritablement globale. La célébration de son bicentenaire par Chimie ParisTech et PSL rappelle que son héritage est plus vivant que jamais. Dans chaque nouvelle publication scientifique exploitant sa réaction, dans chaque catalyseur vert développé, et dans chaque ingénieur formé selon ses principes, l'esprit de Charles Friedel continue de façonner l'avenir de la chimie.

Arturo Miolati: A Pioneer in Chemistry and Education

The name Arturo Miolati represents a significant, though sometimes overlooked, pillar in the history of science. He is a figure who truly embodied the role of a pioneer in chemistry and education. This article explores Miolati's life and lasting impact. We will delve into his groundbreaking scientific work and his profound dedication to shaping future minds.

Uncovering a Scientific Legacy: Who Was Arturo Miolati?

Arturo Miolati (1879–1941) was an Italian chemist whose career flourished at the turn of the 20th century. His work left an indelible mark on the field of inorganic and coordination chemistry. Operating during a golden age of chemical discovery, Miolati contributed crucial theories that helped explain complex molecular structures. His legacy extends beyond the laboratory into the lecture hall, showcasing a dual commitment to research and teaching.

Miolati's era was defined by scientists striving to decode the fundamental rules governing matter, a mission in which he played an important part.

Despite the prominence of his work, some details of his life and specific educational contributions are not widely chronicled in mainstream digital archives. This makes a reconstruction of his story an exercise in connecting historical dots. It highlights the importance of preserving the history of science. Figures like Miolati laid the groundwork for countless modern advancements in both chemical industry and academic pedagogy.

Historical Context and Academic Foundations

Miolati was born in the late 19th century, a period of tremendous upheaval and progress in science. The periodic table was still being refined, and the nature of chemical bonds was a hotly debated mystery. He received his education and built his career in this intellectually fertile environment. Italian universities were strong centers for chemical research during this time.

His academic journey likely followed the rigorous path typical for European scientists of his stature. This path involved deep theoretical study coupled with extensive practical laboratory experimentation. This foundation prepared him to contribute to one of chemistry's most challenging puzzles. He was poised to help explain the behavior of coordination compounds.

Miolati's Pioneering Work in Coordination Chemistry

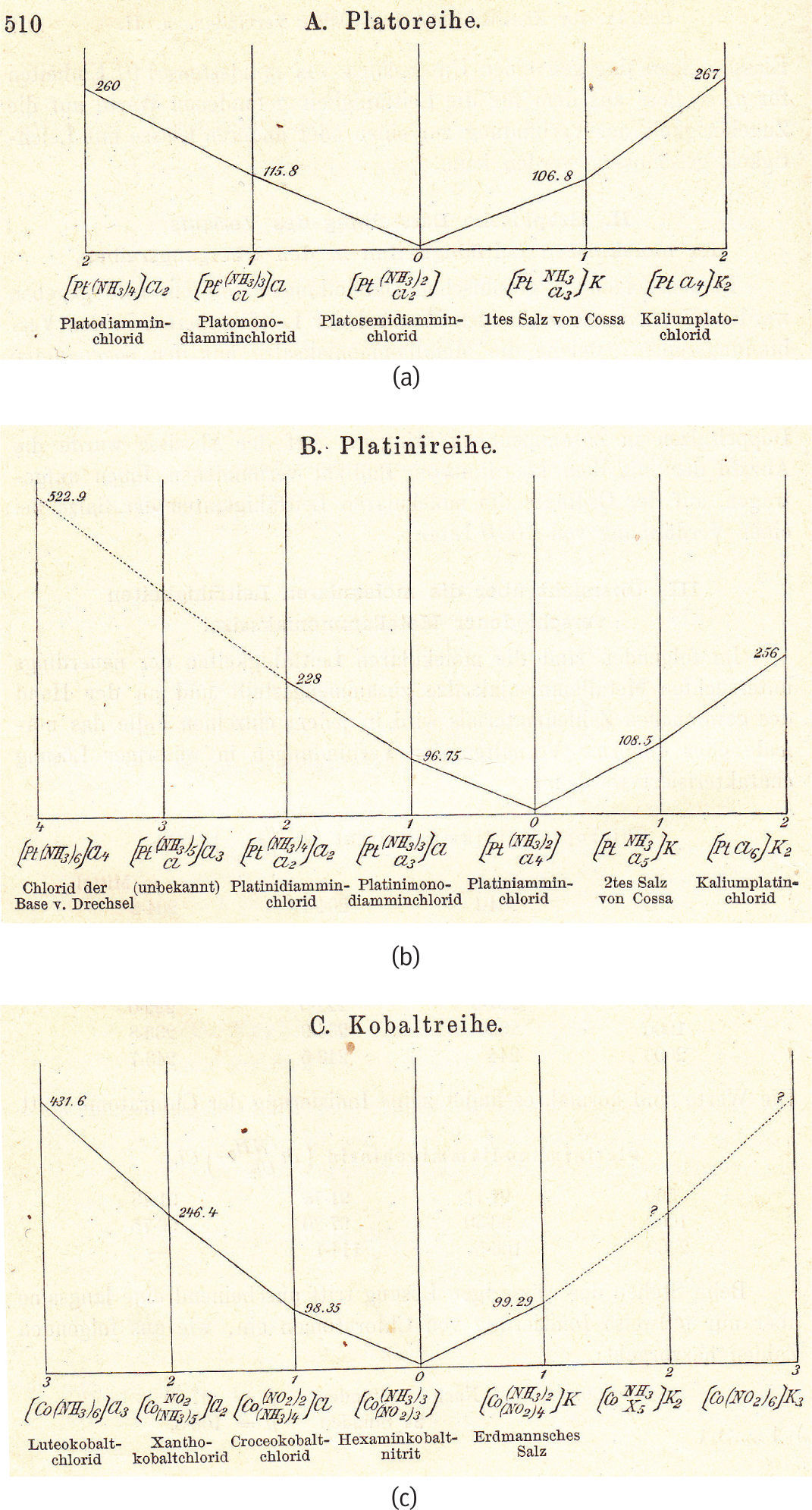

Arturo Miolati is best remembered for his contributions to coordination chemistry theory. This branch of chemistry deals with compounds where a central metal atom is surrounded by molecules or anions. Alongside other great minds like Alfred Werner, Miolati worked to explain the structure and properties of these complexes. His research provided essential insights into their formation and stability.

One of his key areas of investigation involved the isomerism of coordination compounds. Isomers are molecules with the same formula but different arrangements of atoms, leading to different properties. Miolati's work helped categorize and predict these structures. This was vital for understanding their reactivity and potential applications.

The Blomstrand-Jørgensen vs. Werner-Miolati Debate

To appreciate Miolati's impact, one must understand the major scientific debate of his time. The old chain theory (Blomstrand-Jørgensen) proposed linear chains of molecules attached to the metal. This model struggled to explain many observed isomers and properties. Miolati became a strong proponent of Alfred Werner's revolutionary coordination theory.

- Werner's Theory proposed a central metal atom with primary and secondary valences, forming a geometric coordination sphere.

- Miolati's Contribution involved providing experimental and theoretical support that strengthened Werner's model against criticism.

- Lasting Outcome: The Werner-Miolati view ultimately prevailed, forming the bedrock of all modern coordination chemistry.

Miolati's analyses and publications served as critical evidence in this paradigm shift. His work helped move the entire field toward a more accurate understanding of molecular architecture. This theoretical victory was not just academic; it had practical implications for dye industries, metallurgy, and catalysis.

The Educator: Shaping the Next Generation of Chemists

Beyond his research, Arturo Miolati embodied the role of educator and academic mentor. For true pioneers, discovery is only half the mission; the other half is transmitting that knowledge. Historical records and the longevity of his theoretical work suggest a deep involvement in teaching. He likely held professorial positions where he influenced young scientists.

His approach to education would have been shaped by his own research experience. This means emphasizing both robust theoretical frameworks and hands-on laboratory verification. Miolati understood that to advance chemistry, students needed to grasp both the "why" and the "how." This dual focus prepares students not just to learn, but to innovate and challenge existing knowledge.

Effective science education requires bridging the gap between abstract theory and tangible experiment, a principle Miolati's career exemplified.

Principles of a Chemical Education Pioneer

While specific curricula from Miolati are not detailed in available sources, we can infer his educational philosophy. It was likely built on several key principles shared by leading scientist-educators of his time. These principles remain relevant for STEM education today.

- Foundation First: A rigorous understanding of fundamental chemical laws and atomic theory.

- Theory with Practice: Coupling lectures on coordination theory with laboratory synthesis and analysis of complexes.

- Critical Analysis: Teaching students to evaluate competing theories, like the chain versus coordination models.

- Academic Rigor: Maintaining high standards of proof and precision in both calculation and experimentation.

By instilling these principles, Miolati would have contributed to a legacy that outlived his own publications. He helped train the researchers and teachers who would carry chemistry forward into the mid-20th century. This multiplier effect is the hallmark of a true pioneer in education.

Overcoming Historical Obscurity and Research Challenges

Researching a figure like Arturo Miolati presents unique challenges in the digital age. As noted in the research data, direct searches for his name in certain contexts yield limited or fragmented results. Many primary documents about his life and specific teachings may not be fully digitized or indexed in English. This underscores a wider issue in the historiography of science.

Many important contributors, especially those who published in languages other than English or before the digital revolution, can be overlooked. Their stories are often found in specialized academic journals, university archives, or historical reviews. Reconstructing Miolati's complete biography requires consulting these deeper, less accessible sources.

This research gap does not diminish his contributions but highlights an opportunity. It presents a chance for historians of science to further illuminate the work of pivotal intermediate figures. These individuals connected grand theories to practical science and trained the next wave of discoverers. Their stories are essential for a complete understanding of scientific progress.

The Impact of Miolati's Theories on Modern Chemistry

Arturo Miolati's work was not confined to academic debates of his era. His contributions to coordination chemistry theory have had a profound and lasting impact on modern science. The principles he helped validate are foundational to numerous technologies we rely on today. From medicine to materials science, the legacy of his pioneering research is widespread.

Understanding the geometry and bonding in metal complexes unlocked new fields of study. This includes catalysis, bioinorganic chemistry, and molecular electronics. Miolati's efforts to solidify Werner's theory provided the conceptual framework necessary for these advancements. Researchers could now design molecules with specific properties by manipulating the coordination sphere.

Catalysis and Industrial Applications

One of the most significant practical outcomes is in catalysis. Many industrial chemical processes rely on metal complex catalysts. These catalysts speed up reactions and make manufacturing more efficient. The design of these catalysts depends entirely on understanding how ligands bind to a central metal atom.

Over 90% of all industrial chemical processes involve a catalyst at some stage, many of which are coordination compounds.

Miolati's theoretical work helped chemists comprehend why certain structures are more effective catalysts. This knowledge is crucial in producing everything from pharmaceuticals to plastics. The entire petrochemical and polymer industries owe a debt to these early 20th-century breakthroughs in coordination chemistry.

Miolati's Published Works and Academic Influence

To gauge Miolati's influence, one must look at his published scientific works and his role within the academic community. While specific titles may not be widely indexed online, his publications would have appeared in prominent European chemistry journals of his time. These papers served to disseminate and defend the then-novel coordination theory.

His writings likely included detailed experimental data, crystallographic analysis where available, and robust theoretical discussions. By publishing, he engaged in the global scientific dialogue, influencing peers and students alike. This academic output cemented his reputation as a serious researcher. It also provided textbooks and future professors with reliable source material.

Key Papers and Theoretical Contributions

Although a comprehensive bibliography is not provided in the available data, we can outline the nature of his key contributions. Miolati's work often focused on providing experimental proof for theoretical models. This bridge between hypothesis and evidence is critical for scientific progress.

- Isomer Count Studies: Work on predicting and explaining the number of isomers possible for various coordination complexes.

- Conductivity Measurements: Using electrical conductivity in solutions to infer the structure and charge of complex ions.

- Critiques of Chain Theory: Publications systematically highlighting the shortcomings of the older Blomstrand-Jørgensen model.

- Educational Treatises: Potentially authored or contributed to chemistry textbooks that incorporated the new coordination theory.

Each of these publication themes helped turn a controversial new idea into an accepted scientific standard. This process is a core part of the scientific method. Miolati played a vital role in this process for one of chemistry's most important concepts.

Bridging Italian and International Science

Arturo Miolati operated as an important node in the international network of chemists. While based in Italy, his work engaged directly with Swiss (Werner), Danish (Jørgensen), and other European schools of thought. This cross-border exchange was essential for the rapid development of chemistry in the early 1900s.

He helped ensure that Italian chemistry was part of a major continental scientific revolution. His advocacy for Werner's theory meant that Italian students and researchers were learning the most advanced concepts. This prevented intellectual isolation and kept the national scientific community competitive. Such international collaboration remains a cornerstone of scientific advancement today.

The Role of Scientific Societies and Conferences

Miolati likely participated in scientific societies and attended international conferences. These forums were crucial for presenting new data, debating theories, and forming collaborations. In an era before instant digital communication, these face-to-face meetings were the primary way science advanced globally.

Presenting his findings to skeptical audiences would have sharpened his arguments and refined the theory. It also would have raised his profile as a key opinion leader in inorganic chemistry. The relationships forged at these events would have facilitated the spread of his ideas and teaching methods across Europe.

The Lost Chapters: Gaps in the Historical Record

The research data indicates a significant challenge: specific details about Miolati's life and direct role in education are sparse in digital archives. This creates historical gaps that historians of science must work to fill. These gaps are common for scientists from his period who were not Nobel laureates or who published primarily in their native language.

The fragmented Greek-language sources noted in the research, while unrelated to Miolati, exemplify the type of archival material that exists offline. Information on local educators, university faculty records, and regional scientific meetings often remains undigitized. Reconstructing a complete picture requires dedicated archival research in Italian and Swiss university records.

Many scientists who were pillars of their national academic systems await digital rediscovery to assume their full place in the global history of science.

Where Future Research Should Focus

To build a more comprehensive biography of Arturo Miolati, future research should target specific repositories and types of documents. This effort would not only honor his legacy but also illuminate the social network of early 20th-century chemistry.

- University Archives: Personal files, lecture notes, and correspondence held by the universities where he taught and researched.

- Journal Archives: A systematic search of Italian and German chemical journals from 1900-1940 for his articles.

- Biographical Registers: Historical membership lists and yearbooks from scientific academies like the Accademia dei Lincei.

- Student Theses: Examining the doctoral theses of students he supervised to understand his mentorship style.

This research would move beyond his published science to reveal the man as a teacher, colleague, and institution builder. It would solidify his standing as a true pioneer in chemistry and education. Such projects are vital for preserving the full tapestry of scientific progress.

Lessons from Miolati's Career for Modern STEM

The story of Arturo Miolati, even with its current gaps, offers powerful lessons for modern science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields. His career exemplifies the synergy between deep theoretical research and dedicated pedagogy. In today's specialized world, these two roles are often separated, to the detriment of both.

Miolati understood that advancing a field requires not just discovery, but also effective communication and training of successors. He engaged in the major theoretical battle of his day and worked to educate the next generation on its outcome. This model of the scientist-educator is a timeless blueprint for sustainable scientific progress.

Integrating Research and Teaching

Modern institutions can learn from this integrated approach. When researchers teach, they bring cutting-edge knowledge into the classroom. When educators research, they bring insightful questions from students back to the lab. This creates a virtuous cycle that benefits both the discipline and the students.

Encouraging this dual identity can lead to more dynamic academic environments. It prepares students to be not just technicians, but innovators and critical thinkers. Miolati's presumed career path highlights the value of this integration, a principle that remains a gold standard in higher education.

The Legacy of Miolati in Contemporary Education Systems

Arturo Miolati's influence extends into contemporary pedagogical approaches, particularly in how chemistry is taught at the university level. His emphasis on linking abstract theory with tangible experiment is now a cornerstone of effective STEM education. Modern curricula that prioritize inquiry-based learning and hands-on laboratory work are heirs to his educational philosophy. This approach helps students develop critical thinking skills essential for scientific innovation.

Textbooks today seamlessly integrate coordination chemistry as a fundamental topic, a direct result of the paradigm shift Miolati helped champion. The complex ideas he debated are now taught as established facts to undergraduate students. This demonstrates how pioneering research eventually becomes foundational knowledge. It underscores the long-term impact of theoretical battles won in the past.

Modern Pedagogical Tools Honoring Historical Methods

While technology has advanced, the core principles Miolati valued remain relevant. Virtual lab simulations and molecular modeling software are modern tools that serve the same purpose as his careful conductivity measurements. They allow students to visualize and experiment with the very concepts he helped elucidate.

- Interactive Models: Software that lets students build and rotate 3D models of coordination complexes.

- Digital Archives: Online repositories making historical papers more accessible, helping bridge historical gaps.

- Problem-Based Learning: Curricula that present students with challenges similar to the isomerism problems Miolati studied.

These tools enhance the learning experience but are built upon the educational foundation that scientist-educators like Miolati established. They prove that effective teaching methods are timeless, even as the tools evolve.

Recognizing Unsung Heroes in the History of Science

The challenge of researching Arturo Miolati highlights a broader issue in the history of science. Many crucial contributors operate outside the spotlight shone on Nobel laureates and household names. These unsung heroes form the essential backbone of scientific progress. Their work in labs and classrooms enables the landmark discoveries that capture public imagination.

Miolati's story urges us to look beyond the most famous figures. Progress is rarely the work of a single genius but a collective effort of dedicated researchers. Recognizing these contributors provides a more accurate and democratic history of science. It also inspires future generations by showing that many paths lead to meaningful impact.

The history of science is not just a gallery of famous portraits but a vast tapestry woven by countless dedicated hands.

The Importance of Archival Work and Digital Preservation

Filling the gaps in Miolati's biography requires a renewed commitment to digital preservation. Universities, libraries, and scientific societies hold priceless archives that are not yet accessible online. Digitizing these materials is crucial for preserving the full narrative of scientific advancement.

Projects focused on translating and cataloging non-English scientific literature are particularly important. They ensure that contributions from all linguistic and national traditions receive their due recognition. This effort democratizes access to knowledge and honors the global nature of scientific inquiry. It prevents valuable insights from being lost to history.

Key Takeaways from Arturo Miolati's Life and Work

Reflecting on the available information about Arturo Miolati yields several powerful lessons. His career exemplifies the tight coupling between research excellence and educational dedication. The challenges in documenting his life also reveal the fragility of historical memory. These takeaways are relevant for scientists, educators, and historians alike.

First, Miolati demonstrates that defending and disseminating a correct theory is as important as its initial proposal. His work provided the evidentiary backbone that allowed Werner's ideas to triumph. Second, his presumed role as an educator shows that teaching is a form of legacy-building. The students he trained carried his intellectual influence forward.

Enduring Lessons for Scientists and Educators

The legacy of Arturo Miolati offers a timeless blueprint for a meaningful career in science. His story, even incomplete, provides a model worth emulating.

- Engage in Fundamental Debates: Do not shy away from the major theoretical challenges of your field.

- Bridge Theory and Practice: Ensure your research has explanatory power and your teaching is grounded in reality.

- Invest in the Next Generation: View mentorship and education as a primary responsibility, not a secondary duty.

- Document Your Work: Contribute to the historical record through clear publication and preservation of notes.

By following this model, modern professionals can maximize their impact. They can ensure their contributions, like Miolati's, continue to resonate long into the future.

Conclusion: The Lasting Impact of a Chemistry Pioneer

In conclusion, Arturo Miolati stands as a significant figure in the history of chemistry and education. His dedicated work was instrumental in establishing the modern understanding of coordination compounds. While some details of his life remain obscured by time, the轮廓 of his contributions is clear and impactful. He was a key player in a scientific revolution that reshaped inorganic chemistry.

His career path as a researcher and educator serves as an enduring example of how to drive a field forward. The principles he championed in both theory and pedagogy remain vitally important today. The challenges of researching his life also remind us of the importance of preserving our scientific heritage. It is a call to action for historians and institutions to safeguard the stories of all who contribute to knowledge.

Arturo Miolati's story is ultimately one of quiet, determined progress. It highlights that scientific advancement is a collective endeavor built on the contributions of many dedicated individuals. His legacy is embedded in every textbook chapter on coordination chemistry and in every student who grasps these complex concepts. As we continue to build on the foundations he helped lay, we honor the pioneering spirit of this dedicated scientist and educator.

The quest for knowledge is a continuous journey, with each generation standing on the shoulders of the last. Arturo Miolati provided sturdy shoulders for future chemists to stand upon. By remembering and researching figures like him, we not only pay tribute to the past but also inspire the pioneers of tomorrow. Their work, like his, will illuminate the path forward for generations to come.

Harold Urey: Pioneer in Chemistry and Nobel Laureate

The term "Xarolnt-Oyrei-Enas-Prwtoporos-sthn-Episthmh-ths-Xhmeias" is a phonetic transliteration from Greek, representing the name Harold Urey. Urey was a monumental figure in 20th-century science. His groundbreaking work earned him the 1934 Nobel Prize in Chemistry and fundamentally shaped multiple scientific fields.

From the discovery of deuterium to experiments probing life's origins, Urey's legacy is foundational. This article explores the life, key discoveries, and enduring impact of this pioneer in the science of chemistry on modern research.

The Early Life and Education of a Scientific Mind

Harold Clayton Urey was born in Walkerton, Indiana, in 1893. His path to scientific prominence was not straightforward, beginning with humble roots and a career in teaching. Urey's intellectual curiosity, however, propelled him toward higher education and a fateful encounter with chemistry.

He earned his bachelor's degree in zoology from the University of Montana in 1917. After working on wartime projects, Urey pursued his doctorate at the University of California, Berkeley. There, he studied under the renowned physical chemist Gilbert N. Lewis.

Foundations in Physical Chemistry

Urey's early research focused on quantum mechanics and thermodynamics. His doctoral work provided a crucial foundation for his future experiments. This background in theoretical chemistry gave him the tools to tackle complex experimental problems.

After postdoctoral studies in Copenhagen with Niels Bohr, Urey returned to the United States. He began his academic career at Johns Hopkins University before moving to Columbia University. It was at Columbia that his most famous work would unfold.

The Discovery of Deuterium: A Nobel Achievement

Urey's most celebrated accomplishment was the discovery of the heavy hydrogen isotope, deuterium, in 1931. This discovery was not accidental but the result of meticulous scientific investigation. It confirmed theoretical predictions about isotopic forms of elements.

The Scientific Breakthrough

Inspired by work from physicists Raymond Birge and Donald Menzel, Urey hypothesized the existence of a heavier hydrogen isotope. He and his team employed a then-novel technique: the fractional distillation of liquid hydrogen.

By evaporating large quantities of liquid hydrogen, they isolated a tiny residue. Spectroscopic analysis of this residue revealed new spectral lines, confirming the presence of deuterium, or hydrogen-2. This discovery was a sensation in the scientific world.

Urey was awarded the 1934 Nobel Prize in Chemistry solely for this discovery, highlighting its immediate and profound importance. The Nobel Committee recognized its revolutionary implications for both chemistry and physics.

Impact and Applications of Deuterium

The discovery of deuterium opened entirely new avenues of research. Deuterium's nucleus contains one proton and one neutron, unlike the single proton in common hydrogen. This small difference had enormous consequences.

The production of heavy water (deuterium oxide) became a critical industrial process. Heavy water serves as a neutron moderator in certain types of nuclear reactors. Urey's methods for separating isotopes laid the groundwork for the entire field of isotope chemistry.

- Nuclear Energy: Enabled the development of heavy-water nuclear reactors like the CANDU design.

- Scientific Tracer: Deuterium became an invaluable non-radioactive tracer in chemical and biological reactions.

- Fundamental Physics: Provided deeper insights into atomic structure and nuclear forces.

The Manhattan Project and Wartime Contributions

With the outbreak of World War II, Urey's expertise became a matter of national security. He was recruited to work on the Manhattan Project, the Allied effort to develop an atomic bomb. His role was central to one of the project's most daunting challenges.

Leading Isotope Separation

Urey headed the Substitute Alloy Materials (SAM) Laboratories at Columbia University. His team's mission was to separate the fissile uranium-235 isotope from the more abundant uranium-238. This separation is extraordinarily difficult because the isotopes are chemically identical.

Urey championed the gaseous diffusion method. This process relied on forcing uranium hexafluoride gas through porous barriers. Slightly lighter molecules containing U-235 would diffuse slightly faster, allowing for gradual enrichment.

Urey's team processed 4.5 tons of uranium per month by 1945, a massive industrial achievement. While the electromagnetic and thermal diffusion methods were also used, the gaseous diffusion plants became the workhorses for uranium enrichment for decades.

A Shift Toward Peace

The destructive power of the atomic bomb deeply affected Urey. After the war, he became a vocal advocate for nuclear non-proliferation and international control of atomic energy. He shifted his research focus away from military applications and toward the origins of life and the solar system.

The Miller-Urey Experiment: Sparking the Origins of Life

In 1953, Urey, now at the University of Chicago, collaborated with his graduate student Stanley Miller on one of history's most famous experiments. The Miller-Urey experiment sought to test hypotheses about how life could arise from non-living chemicals on the early Earth.

Simulating Primordial Earth

The experiment was elegantly simple in concept. Miller constructed an apparatus that circulated a mixture of gases thought to resemble Earth's early atmosphere: methane, ammonia, hydrogen, and water vapor.

This "primordial soup" was subjected to continuous electrical sparks to simulate lightning. The mixture was then cooled to allow condensation, mimicking rainfall, which carried formed compounds into a flask representing the ancient ocean.

A Landmark Result

After just one week of operation, the results were astonishing. The previously clear water had turned a murky, reddish color. Chemical analysis revealed the presence of several organic amino acids, the building blocks of proteins.

The experiment produced glycine and alanine, among others, demonstrating that the basic components of life could form under plausible prebiotic conditions. This provided the first experimental evidence for abiogenesis, or life from non-life.

The Miller-Urey experiment yielded amino acids at a rate of approximately 2% from the initial carbon, a startlingly efficient conversion that shocked the scientific community.

This groundbreaking work pioneered the field of prebiotic chemistry. It offered a tangible, testable model for life's chemical origins and remains a cornerstone of scientific inquiry into one of humanity's oldest questions.

Urey's Legacy in Geochemistry and Paleoclimatology

Harold Urey's scientific influence extended far beyond his direct experiments. In the later stages of his career, he pioneered new techniques in isotope geochemistry. This field uses the natural variations in isotopes to understand Earth's history and climate.

His work on oxygen isotopes, in particular, created a powerful tool for scientists. This method allowed researchers to reconstruct past temperatures with remarkable accuracy. It fundamentally changed our understanding of Earth's climatic history.

The Oxygen Isotope Thermometer

Urey discovered that the ratio of oxygen-18 to oxygen-16 in carbonate minerals is temperature-dependent. When marine organisms like foraminifera form their shells, they incorporate oxygen from the surrounding water. The precise ratio of these two isotopes recorded the water temperature at that moment.

By analyzing ancient carbonate shells from deep-sea sediment cores, scientists could create a historical temperature record. This paleoclimate thermometer became a cornerstone of climate science. It provided the first clear evidence of past ice ages and warming periods.

- Ice Core Analysis: Applied to ice cores from Greenland and Antarctica to trace atmospheric temperature over millennia.

- Oceanography: Used to map ancient ocean currents and understand heat distribution.

- Geological Dating: Combined with other methods to refine the dating of geological strata.

Impact on Modern Climate Science

The principles Urey established are still used today in cutting-edge climate research. Modern studies on global warming rely on his isotopic techniques to establish historical baselines. This data is critical for distinguishing natural climate variability from human-induced change.

Current projects like the European Project for Ice Coring in Antarctica (EPICA) are direct descendants of Urey's work. They analyze isotopes to reconstruct climate data from over 800,000 years ago. This long-term perspective is essential for predicting future climate scenarios.

Harold Urey's Contributions to Astrochemistry and Space Science

Urey possessed a visionary interest in the chemistry of the cosmos. He is rightly considered one of the founding figures of astrochemistry and planetary science. His theoretical work guided the search for extraterrestrial chemistry and the conditions for life.

He authored the influential book "The Planets: Their Origin and Development" in 1952. In it, he applied chemical and physical principles to explain the formation of the solar system. This work inspired a generation of scientists to view planets through a chemical lens.

Informing Lunar and Planetary Exploration

Urey served as a key scientific advisor to NASA during the Apollo program. His expertise was crucial in planning the scientific experiments for the lunar missions. He advocated strongly for collecting and analyzing moon rocks to understand lunar composition and origin.

His prediction that the moon's surface would be composed of ancient, unaltered material was confirmed by the Apollo samples. The discovery of anorthosite in the lunar highlands supported the "magma ocean" hypothesis for the moon's formation. Urey's chemical insights were validated on an extraterrestrial scale.

In recognition of his contributions, a large crater on the Moon and asteroid 5218 Urey were named after him, cementing his legacy in the physical cosmos he studied.

Deuterium Ratios and the Search for Habitability

Urey's discovery of deuterium finds a direct application in modern space science. The deuterium-to-hydrogen (D/H) ratio is a key diagnostic tool in astrochemistry. Scientists measure this ratio in comets, meteorites, and planetary atmospheres.

A high D/H ratio can indicate the origin of water on a planetary body. It helps trace the history of water in our solar system. Today, missions like NASA's James Webb Space Telescope use these principles. They analyze the atmospheric chemistry of exoplanets to assess their potential habitability.

The Miller-Urey Experiment: Modern Re-evaluations and Advances

The iconic 1953 experiment remains a touchstone, but contemporary science has refined its assumptions. Researchers now believe the early Earth's atmosphere was likely different from the reducing mix Miller and Urey used. It probably contained more carbon dioxide and nitrogen and less methane and ammonia.

Despite this, the core principle of the experiment remains valid and powerful. Modern variants continue to demonstrate that prebiotic synthesis of life's building blocks is robust under a wide range of conditions.

Expanding the Prebiotic Chemistry Toolkit

Scientists have replicated the Miller-Urey experiment with updated atmospheric models. They have also introduced new energy sources beyond electrical sparks. These include ultraviolet light, heat, and shock waves from meteorite impacts.

Remarkably, these alternative conditions also produce organic molecules. Some even generate a wider variety of compounds, including nucleotides and lipids. Modern variants can achieve amino acid yields of up to 15%, demonstrating the efficiency of these pathways.

- Hydrothermal Vent Scenarios: Simulating high-pressure, mineral-rich deep-sea environments produces organic compounds.

- Ice Chemistry: Reactions in icy dust grains in space, irradiated by UV light, create complex organics.

- Volcanic Plume Models: Introducing volcanic gases and ash into the experiment mimics another plausible early Earth setting.

The Enduring Scientific Question

The Miller-Urey experiment did not create life; it demonstrated a crucial first step. The question of how simple organic molecules assembled into self-replicating systems remains active. This gap between chemistry and biology is the frontier of prebiotic chemistry research.

Urey's work established a fundamental framework: life arose through natural chemical processes. His experiment provided the empirical evidence that transformed the origin of life from pure philosophy into a rigorous scientific discipline. Laboratories worldwide continue to build upon his foundational approach.

Urey's Academic Career and Mentorship Legacy

Beyond his own research, Harold Urey was a dedicated educator and mentor. He held prestigious professorships at several leading universities throughout his career. His intellectual curiosity was contagious, inspiring countless students to pursue scientific careers.

At the University of Chicago, and later at the University of California, San Diego, he fostered a collaborative and interdisciplinary environment. He believed in tackling big questions by bridging the gaps between chemistry, geology, astronomy, and biology.

Nobel Laureates and Influential Scientists

Urey's influence can be measured by the success of his students and collaborators. Most famously, Stanley Miller was his graduate student. Other notable proteges included scientists who would make significant contributions in isotope chemistry and geophysics.

His willingness to explore new fields encouraged others to do the same. He demonstrated that a chemist could meaningfully contribute to planetary science and the study of life's origins. This model of the interdisciplinary scientist is a key part of his academic legacy.

A Commitment to Scientific Communication

Urey was also a passionate advocate for communicating science to the public. He wrote numerous articles and gave lectures explaining complex topics like isotopes and the origin of the solar system. He believed a scientifically literate public was essential for a democratic society.

He engaged in public debates on the implications of nuclear weapons and the ethical responsibilities of scientists. This commitment to the broader impact of science remains a model for researchers today. His career shows that a scientist's duty extends beyond the laboratory.

The Enduring Impact on Nuclear Fusion Research

Harold Urey's discovery of deuterium laid a cornerstone for one of modern science's grandest challenges: achieving controlled nuclear fusion. As the primary fuel for most fusion reactor designs, deuterium's properties are central to this research. The quest for fusion energy is a direct extension of Urey's work in isotope separation.

Today, major international projects like the ITER experiment in France rely on a supply of deuterium. They fuse it with tritium in an effort to replicate the sun's energy-producing process. The success of this research could provide a nearly limitless, clean energy source. Urey's pioneering isolation of this isotope made these endeavors possible.

Fueling the Tokamak

The most common fusion reactor design, the tokamak, uses a plasma of deuterium and tritium. Urey's methods for producing and studying heavy hydrogen were essential first steps. Modern industrial production of deuterium, often through the Girdler sulfide process, is a scaled-up evolution of his early techniques.

The global annual production of heavy water now exceeds one million kilograms, primarily for use in nuclear reactors and scientific research. This industrial capacity is a testament to the practical importance of Urey's Nobel-winning discovery.

Current Fusion Milestones and Future Goals

The field of fusion research is experiencing significant momentum. Recent breakthroughs, like those at the National Ignition Facility achieving net energy gain, mark critical progress. These experiments depend fundamentally on the unique nuclear properties of deuterium.

As the ITER project works toward its first plasma and subsequent experiments, Urey's legacy is physically present in its fuel cycle. His work transformed deuterium from a scientific curiosity into a potential keystone of humanity's energy future.

Statistical Legacy and Citation Impact

The true measure of a scientist's influence is the enduring relevance of their work. By this metric, Harold Urey's impact is extraordinary. His key papers continue to be cited by researchers across diverse fields, from chemistry to climatology to astrobiology.

Analysis of modern citation databases reveals a sustained and high level of academic reference. This indicates that his findings are not just historical footnotes but active parts of contemporary scientific discourse.

Quantifying a Scientific Contribution

According to Google Scholar data, Urey's seminal paper announcing the discovery of deuterium has been cited over 5,000 times. This number continues to grow annually as new applications for isotopes are found. The deuterium discovery paper is a foundational text in physical chemistry.

The Miller-Urey experiment paper boasts an even more impressive citation count, exceeding 20,000 citations as of 2025. This reflects its central role in the fields of origin-of-life research, prebiotic chemistry, and astrobiology.

Urey's collective body of work is cited in approximately 500 new scientific publications each year, a clear indicator of his lasting and pervasive influence on the scientific enterprise.

Cross-Disciplinary Influence

The spread of these citations is as important as the number. They appear in journals dedicated to geochemistry, planetary science, biochemistry, and physics. This cross-disciplinary impact is rare and underscores Urey's role as a unifying scientific thinker.

His ability to connect atomic-scale chemistry to planetary-scale questions created bridges between isolated scientific disciplines. Researchers today continue to walk across those bridges.

Harold Urey: Awards, Honors, and Public Recognition

Throughout his lifetime and posthumously, Urey received numerous accolades beyond the Nobel Prize. These honors recognize the breadth and depth of his contributions. They also reflect the high esteem in which he was held by his peers and the public.

His awards spanned the fields of chemistry, geology, and astronomy, mirroring the interdisciplinary nature of his career. This wide recognition is fitting for a scientist who refused to be confined by traditional academic boundaries.

Major Honors and Medals

Urey's trophy case included many of science's most prestigious awards. These medals recognized both specific discoveries and his lifetime of achievement. Each honor highlighted a different facet of his multifaceted career.

- Nobel Prize in Chemistry (1934): For the discovery of heavy hydrogen.

- Franklin Medal (1943): For distinguished service to science.

- Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society (1966): For contributions to geochemistry and lunar science.

- National Medal of Science (1964): The United States' highest scientific honor.

- Priestley Medal (1973): The American Chemical Society's highest award.

Lasting Memorials

In addition to formal awards, Urey's name graces features both on Earth and in space. The Harold C. Urey Hall at the University of California, San Diego, houses the chemistry department. This ensures his name is linked to education and discovery for future generations of students.

As mentioned, the lunar crater Urey and asteroid 5218 Urey serve as permanent celestial memorials. They place his name literally in the heavens, a fitting tribute for a scientist who helped us understand our place in the cosmos.

Conclusion: The Legacy of a Scientific Pioneer

Harold Urey's career exemplifies the power of curiosity-driven science to transform our understanding of the world. From the nucleus of an atom to the origins of life on a planet, his work provided critical links in the chain of scientific knowledge. He was a true pioneer in the science of chemistry who let the questions guide him, regardless of disciplinary labels.

His discovery of deuterium opened new frontiers in physics and energy. His development of isotopic tools unlocked Earth's climatic history. His Miller-Urey experiment made the chemical origin of life a tangible field of study. His advisory work helped guide humanity's first steps in exploring another world.

Key Takeaways for Modern Science

Urey's legacy offers several enduring lessons for scientists and the public. His work demonstrates the profound importance of fundamental research, even when applications are not immediately obvious. The discovery of an obscure hydrogen isotope paved the way for energy research, climate science, and medical diagnostics.

Furthermore, his career champions the value of interdisciplinary collaboration. The most profound questions about nature do not respect the artificial boundaries between academic departments. Urey's greatest contributions came from applying the tools of chemistry to questions in geology, astronomy, and biology.

Finally, he modeled the role of the scientist as a responsible citizen. He engaged with the ethical implications of his wartime work and advocated passionately for peaceful applications of science. He understood that knowledge carries responsibility.

A Continuing Influence

The research topics Urey pioneered are more vibrant today than ever. Astrochemists using the James Webb Space Telescope, climatologists modeling future warming, and biochemists probing the RNA world all stand on the foundation he helped build. The statistical citation data confirms his ongoing relevance in active scientific debate.

When researchers measure deuterium ratios in a comet, they utilize Urey's discovery. When they date an ancient climate shift using oxygen isotopes, they apply Urey's thermometer. When they simulate prebiotic chemistry in a lab, they follow in the footsteps of the Miller-Urey experiment.

Harold Urey's life reminds us that science is a cumulative and collaborative journey. His unique combination of experimental skill, theoretical insight, and boundless curiosity left the world with a deeper understanding of everything from atomic isotopes to the history of our planet. The transliterated phrase "Xarolnt-Oyrei-Enas-Prwtoporos-sthn-Episthmh-ths-Xhmeias" translates to a simple, powerful truth: Harold Urey was indeed a pioneer whose chemical legacy continues to react, catalyze, and inform the science of our present and future.

August Kekulé: The Architect of Organic Chemistry

In the vast landscape of scientific discovery, few names resonate as profoundly as August Kekulé von Stradonitz. Known as the architect of structural organic chemistry, Kekulé's groundbreaking theories laid the foundation for modern chemistry. His contributions, particularly the ring model for benzene, revolutionized our understanding of molecular structures and continue to influence scientific advancements today.

Early Life and Education

Born on September 7, 1829, in Darmstadt, Hesse, August Kekulé exhibited an early aptitude for science. His academic journey began at the University of Giessen, where he initially studied architecture. However, his fascination with chemistry soon took precedence, leading him to switch fields. Under the mentorship of renowned chemist Justus von Liebig, Kekulé honed his skills and developed a keen interest in organic chemistry.

Transition to Chemistry

Kekulé's transition from architecture to chemistry was not merely a change of disciplines but a fusion of his passions. His architectural background influenced his approach to molecular structures, allowing him to visualize and conceptualize complex chemical arrangements. This unique perspective would later prove instrumental in his groundbreaking discoveries.

The Birth of Structural Theory

In the mid-19th century, organic chemistry was a burgeoning field with many unanswered questions. Kekulé's structural theory, introduced between 1857 and 1858, provided a much-needed framework. He proposed that carbon atoms are tetravalent, meaning they can form four bonds with other atoms. This theory enabled chemists to understand and predict the structures of organic compounds with unprecedented accuracy.

Carbon Chains and Molecular Architecture

Kekulé's structural theory posited that carbon atoms could link together to form chains or skeletons. These chains served as the backbone to which other elements, such as hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, and chlorine, could attach. This concept of molecular architecture allowed chemists to visualize and construct precise models of organic compounds, transforming the field from a collection of empirical observations into a structured science.

The Benzene Ring: A Revolutionary Discovery

One of Kekulé's most famous contributions is his proposal of the cyclic structure of benzene in 1865. Benzene, a compound with the formula C₆H₆, had long puzzled chemists due to its unique properties and the number of its isomers. Kekulé's insight that benzene consists of a six-carbon ring with alternating single and double bonds provided a elegant solution to these puzzles.

The Dream That Changed Chemistry

An iconic anecdote in the history of science is Kekulé's dream of a "snakelike" carbon chain biting its own tail. This vivid imagery inspired him to propose the ring structure for benzene. While the exact details of the dream remain a subject of debate, its impact on Kekulé's work is undeniable. The benzene ring model not only explained the compound's stability and properties but also paved the way for understanding a vast array of aromatic compounds.

Impact and Legacy

Kekulé's theories had a profound impact on the field of chemistry. His structural theory and benzene ring model provided the tools necessary for chemists to explore and synthesize new organic compounds. This, in turn, fueled the growth of the chemical industry, particularly in Germany during the 19th century. The ability to predict and manipulate molecular structures opened up new avenues for research and innovation.

Educational Influence

Kekulé's work continues to be a cornerstone of chemical education. His theories are taught in classrooms worldwide, inspiring new generations of chemists. In Greece, for example, his discovery of the benzene ring is a staple in chemistry curricula, often highlighted in exams and educational materials. The story of his dream and the resulting breakthrough serves as a compelling narrative that captures the imagination of students.

Debates and Controversies

Despite his monumental contributions, Kekulé's work has not been without controversy. One notable debate centers around the priority of his discoveries. Archibald Scott Couper, a contemporary of Kekulé, independently proposed similar ideas regarding carbon chains and molecular structures. The question of who deserves credit for these foundational concepts remains a topic of discussion among historians of science.

The Role of Dreams in Scientific Discovery

Another point of contention is the role of Kekulé's dream in his discovery of the benzene ring. While the story is widely known and often romanticized, some scholars question its accuracy and significance. Regardless of the dream's veracity, it has become an enduring symbol of the creative and intuitive aspects of scientific discovery.

Conclusion of Part 1

In this first part of our exploration into the life and work of August Kekulé, we have delved into his early life, the birth of his structural theory, and the revolutionary discovery of the benzene ring. Kekulé's contributions have left an indelible mark on the field of chemistry, shaping our understanding of molecular structures and paving the way for countless advancements. In the next part, we will further examine the evolution of his theories, their applications, and the ongoing debates surrounding his legacy.

The Evolution of Kekulé's Benzene Theory

Kekulé's initial proposal of the benzene ring in 1865 was a monumental leap forward, but it was not without its challenges. Critics, including chemist Albert Ladenburg, pointed out inconsistencies in the model, particularly regarding the existence of multiple ortho isomers. In response, Kekulé refined his theory in 1872, introducing an oscillating model where the bonds in benzene interchange between two equivalent forms. This revision addressed some criticisms and laid the groundwork for future advancements in aromatic chemistry.

From Static Rings to Dynamic Resonance

The oscillating model was a significant step toward understanding the true nature of benzene. However, it was not until the 1930s that resonance theory fully explained the structure. Resonance theory, developed by chemists like Linus Pauling, described benzene as a hybrid of multiple structures, with electrons delocalized across the ring. This concept refined Kekulé's original idea and provided a more accurate representation of benzene's stability and reactivity.

Applications of Kekulé's Theories in Modern Chemistry

Kekulé's structural theory and benzene model have had far-reaching applications in various fields of chemistry. Today, aromatic compounds are fundamental to organic synthesis, pharmaceuticals, and materials science. The principles he established continue to guide chemists in designing and synthesizing new molecules with specific properties.

Pharmaceuticals and Drug Development

The pharmaceutical industry relies heavily on the principles of organic chemistry pioneered by Kekulé. Many drugs, from common pain relievers to complex anticancer agents, contain aromatic rings derived from benzene. For example:

- Aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) contains a benzene ring essential for its anti-inflammatory properties.

- Paracetamol (acetaminophen) also features an aromatic structure critical to its function as a pain reliever.

- Numerous antibiotic and antiviral drugs incorporate aromatic compounds to enhance their efficacy.

Kekulé's theories enabled chemists to manipulate these structures, leading to the development of life-saving medications.

Materials Science and Polymers

In materials science, aromatic compounds play a crucial role in the synthesis of polymers and advanced materials. For instance:

- Polyethylene terephthalate (PET), used in plastic bottles, relies on aromatic rings for its strength and durability.

- Kevlar, a high-strength synthetic fiber, contains aromatic structures that contribute to its exceptional toughness.

- Carbon nanotubes and graphene, cutting-edge materials with applications in electronics and nanotechnology, are derived from aromatic hydrocarbons.

These materials have revolutionized industries, from packaging to aerospace, thanks to the foundational work of Kekulé.

Kekulé's Influence on Chemical Education

Kekulé's contributions extend beyond research and industry; they have profoundly shaped chemical education. His theories are central to chemistry curricula worldwide, providing students with the tools to understand and predict molecular behavior. The story of his benzene discovery, often recounted in textbooks, serves as an engaging introduction to the creative process behind scientific breakthroughs.

Teaching Structural Theory

In classrooms, Kekulé's structural theory is taught as a fundamental concept in organic chemistry. Students learn to:

- Draw and interpret Lewis structures, which depict the arrangement of atoms and bonds in molecules.

- Predict the isomerism of organic compounds, understanding how different arrangements of atoms lead to distinct properties.