Introduction to Ghib Ojisan: A Tale of Warmth and Wisdom

Ghib Ojisan, or "Aunt Ghibli," is a beloved mascot representing the iconic Japanese animation studio, Studio Ghibli. Founded in 1985 by directors Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata, Studio Ghibli has become a cornerstone of animated filmmaking, known for its rich imagery, imaginative storytelling, and deep emotional resonance. At the heart of this studio lies Ghib Ojisan—part symbol, part mascot—who has become synonymous with Studio Ghibli's warm, whimsical spirit.

The Origin of Ghib Ojisan

The origins of Ghib Ojisan trace back to the early days of Studio Ghibli. Hayao Miyazaki is often credited with creating this character as a playful and endearing representation of the studio. Ghib Ojisan is a gentle, bespectacled old man dressed in traditional Japanese attire, holding a large teapot filled with a warm, comforting beverage. He embodies the friendly and inviting nature of the studio and its creators, providing a recognizable face for fans around the world.

The name "Ojisan" translates to "aunt" in Japanese, which might seem unconventional given that the character is male. However, this is intentional, serving to reinforce the sense of grandmotherly warmth and comfort often associated with "ojousama," which means "miss" or "young lady" and can also connote a nurturing and caring figure. This dual-meaning adds to the character’s charm and universality.

The Significance of Ghib Ojisan

Ghib Ojisan is more than just a mascot; he is a living testament to Studio Ghibli’s mission and values. The character appears in various forms across the studio’s films, merchandise, and public appearances, reinforcing the idea that Studio Ghibli remains connected to the hearts of its audience. Whether it's in promotional materials or official merchandise, Ghib Ojisan reminds viewers of the studio’s enduring legacy and its commitment to storytelling.

Furthermore, Ghib Ojisan serves as a bridge between Studio Ghibli and its international fan base. His presence is felt worldwide, appearing at film festivals, conventions, and promotional events. Through Ghib Ojisan, audiences can feel a sense of connection to Studio Ghibli, even if they have never visited his home country.

Ghib Ojisan in Animated Films

In several of Studio Ghibli’s animated films, Ghib Ojisan appears either as a minor character or in brief cameos. For instance, in the movie “Howl’s Moving Castle” (2004), a scene features a small elderly person resembling Ghib Ojisan standing in a garden. Similarly, in “My Neighbor Totoro” (1988), Ghib Ojisan makes an appearance through a caricatured version of himself in a painting. These minor appearances add to the overall atmosphere of warmth and familiarity within the films.

The character’s inclusion in these films not only reinforces the themes of home, family, and community that are prevalent throughout Studio Ghibli works but also acts as a form of internal branding. It ensures that Studio Ghibli’s core values and spirit are consistently represented, making Ghib Ojisan an integral component of the studio’s creative output.

The Evolution of Ghib Ojisan

Since Ghib Ojisan’s creation, the character has undergone some subtle evolutions. Early depictions in promotional materials often showed a more elderly-looking grandfather figure. However, over time, the character has undergone minor adjustments to maintain a youthful and relatable appeal while keeping true to his original essence. Modern versions of Ghib Ojisan appear as a more robust and energetic figure, reflecting the studio’s ongoing commitment to timeless storytelling.

One of the significant changes in Ghib Ojisan’s portrayal involves his age range. While still embodying the wisdom and kind-heartedness of an older generation, Ghib Ojisan’s depiction has evolved to suggest a younger, more vibrant old man. This reflects the changing demographic of Studio Ghibli’s fan base and the studio’s desire to maintain relevance across generations. Despite these slight shifts, the core qualities associated with Ghib Ojisan—warmth, patience, and understanding—remain constant.

Ghib Ojisan in Merchandise and Marketing

Ghib Ojisan plays a crucial role in Studio Ghibli’s marketing strategy, both domestically and internationally. From keychains to stuffed toys, Ghib Ojisan-themed merchandise is ubiquitous at Studio Ghibli events and online stores. His presence adds a personal touch, allowing fans to bring a piece of Studio Ghibli’s spirit into their homes. This merchandise is designed not only to sell products but also to evoke a sense of nostalgia and connection to the films and characters.

Ghib Ojisan is also a vital component of Studio Ghibli’s public appearances. He frequently makes guest appearances at film festivals and conventions, where he interacts with attendees, signs autographs, and poses for photos. These interactions strengthen the bond between Studio Ghibli and its audience, making each fan feel personally connected to the studio and its creations.

The popularity of Ghib Ojisan extends beyond physical merchandise. He appears in digital formats such as social media posts and promotional videos, further solidifying his status as a recognizable and beloved figure. By maintaining a consistent and engaging presence both physically and online, Studio Ghibli ensures that Ghib Ojisan remains a constant source of joy and inspiration for fans.

Ghib Ojisan’s Impact on Studio Ghibli’s Fan Base

Ghib Ojisan's enduring presence has a profound impact on Studio Ghibli's fan base, fostering a sense of community and shared experience. Fans often form a strong emotional bond with the character, seeing him as a familiar and comforting figure. This connection transcends cultural and geographical boundaries, making Ghib Ojisan a universal symbol that resonates with audiences worldwide. Many fans find solace in his wise and caring demeanor, creating a feeling of belonging that extends far beyond the films themselves.

A significant aspect of Ghib Ojisan’s appeal lies in his ability to evoke nostalgia. Whether through his appearance in merchandize or his cameo in films, Ghib Ojisan serves as a tangible reminder of Studio Ghibli’s rich history and artistic vision. This nostalgia helps fans of all ages relive cherished moments and connect with the timeless themes that run through Studio Ghibli’s work. By tapping into these nostalgic feelings, Ghib Ojisan becomes an anchor point that binds current and past fans together.

Ghib Ojisan also plays a pivotal role in creating a positive community atmosphere. Whether during fan gatherings, film screenings, or merchandise events, his presence brings people together. Fans often share stories, memories, and feelings about their favorite films, forming bonds that transcend individual experiences. The character’s kindness and warmth create an inclusive environment where everyone feels welcome and valued, promoting a sense of unity among fans.

Global Recognition and Fan Interaction

Internationally, Ghib Ojisan’s recognition and popularity extend far and wide. His image appears not only in Japan but also on store shelves across Europe, North America, and beyond. This global reach has allowed Studio Ghibli to cultivate a diverse and international fan base, many of whom may have little to no knowledge of Japanese culture but still appreciate the character’s universal appeal. The character’s adaptability across different cultures makes Ghib Ojisan a powerful ambassador for Studio Ghibli’s work.

Studio Ghibli actively engages with fans through various channels, including social media, fan communities, and conventions. At events like San Diego Comic-Con or Japan Expo, Ghib Ojisan regularly participates in meet-and-greets, signing sessions, and photo opportunities. These interactions provide fans with a unique and memorable experience, creating lasting memories and strengthening the bond between Studio Ghibli and its audience. Social media platforms like Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook further amplify Ghib Ojisan’s impact, allowing fans from different parts of the world to communicate and share their enthusiasm.

Ghib Ojisan’s global presence is enhanced by various campaigns and initiatives led by Studio Ghibli. For example, the "Studio Ghibli Festival," held annually in select cities around the world, features Ghib Ojisan prominently. During these festivals, the character becomes a central figure, participating in screenings, workshops, and special events. Such efforts not only draw attention to Studio Ghibli’s work but also create a festive and community-oriented atmosphere that celebrates the studio’s contributions to animation.

Legacy and Future of Ghib Ojisan

Looking to the future, Ghib Ojisan continues to play a vital role in preserving and promoting Studio Ghibli’s legacy. As the studio faces new challenges and embraces emerging technologies, Ghib Ojisan remains a constant source of stability and reassurance. His enduring presence ensures that the spirit of Studio Ghibli’s creative vision lives on, inspiring new generations of animators and filmmakers.

The legacy of Ghib Ojisan can be seen in the way he influences both current and aspiring filmmakers. Many young animators draw inspiration from his warm, gentle persona and the values he represents. In a rapidly changing industry, Ghib Ojisan embodies the enduring qualities of storytelling, creativity, and heart that define Studio Ghibli’s work. His presence serves as a reminder of the importance of maintaining a creative and compassionate approach to filmmaking, ensuring that Studio Ghibli continues to thrive and inspire future generations.

Additionally, Ghib Ojisan’s future involves continued innovation and evolution. While maintaining his core attributes, the character may undergo subtle changes to better reflect the evolving tastes and values of the modern audience. By balancing tradition with contemporary sensibilities, Studio Ghibli can ensure that Ghib Ojisan remains relevant and beloved for years to come. Through these efforts, Ghib Ojisan’s legacy will continue to grow, solidifying his place as a beloved and iconic figure in the world of animation.

Closing Thoughts

In conclusion, Ghib Ojisan is more than just a mascot; he is a cherished symbol of Studio Ghibli’s enduring legacy and artistic vision. His gentle presence and kindhearted demeanor have fostered a strong emotional connection with millions of fans around the world. By embodying the warmth and wisdom of the past, Ghib Ojisan remains a beacon of hope and inspiration, continuing to guide Studio Ghibli through its remarkable journey in the ever-evolving landscape of animation. As we look forward, Ghib Ojisan’s future holds endless possibilities, ensuring that Studio Ghibli’s spirit will continue to captivate and uplift audiences for generations to come.

The legacy of Ghib Ojisan is not merely a testament to Studio Ghibli’s success but also a celebration of the power of storytelling and the enduring impact of a well-loved character. His presence continues to enrich the lives of countless individuals, reminding us all of the magic and joy that comes from great stories and the unwavering support of a dedicated fan base.

Cultural Impact and International Influence

The cultural impact of Ghib Ojisan on Japan and the world goes beyond mere representation; it profoundly shapes the perception of Japanese animation and culture. Through Ghib Ojisan, Studio Ghibli has successfully bridged cultural divides, spreading the message of Japanese animation to countries around the globe. This global influence is evident in the way Ghib Ojisan is celebrated during events like the Ottawa Animation Festival and the Annecy International Animation Film Festival, where his presence draws crowds and sparks conversations about the artistry and values of Studio Ghibli.

Culturally speaking, Ghib Ojisan’s character resonates deeply with themes of familial love and community, values that are central to Japanese society. His traditional Japanese attire and the cozy, homely settings in which he typically appears reflect the cultural aesthetics and values cherished by Japanese people. By featuring Ghib Ojisan in these contexts, Studio Ghibli not only celebrates the cultural heritage of Japan but also invites non-Japanese audiences to appreciate and embrace these values.

Moreover, Ghib Ojisan’s cultural significance is heightened by his role in educational and cultural exchange programs. Schools and universities often use Ghib Ojisan to teach students about Japan and Japanese culture. Through storytelling and interactive activities, Ghib Ojisan provides a tangible link to the cultural richness of Japan, helping children understand and appreciate the diversity of cultures globally. This educational approach makes Ghib Ojisan a valuable tool in promoting cultural understanding and empathy.

Impact on Anime Industry and Beyond

Ghib Ojisan’s influence extends beyond Studio Ghibli itself, impacting the broader anime industry and popular culture. His popularity sets a standard for other anime characters, particularly those aiming to convey warmth, wisdom, and community. Other anime studios have recognized the success of Ghib Ojisan and incorporated similar archetypes into their own characters. For instance, characters like Grandpa in "Grave of the Fireflies" and Oji-chan in "Puella Magi Madoka Magica" draw inspiration from Ghib Ojisan’s character traits and thematic elements.

Furthermore, the success of Ghib Ojisan has inspired a wider cultural phenomenon, influencing fashion, design, and marketing strategies. Merchandise that incorporates Ghib Ojisan’s image, such as t-shirts, mugs, and phone cases, becomes a fashionable accessory that fans display to show their love for Studio Ghibli. This trend not only boosts sales but also reinforces the brand identity and cultural significance of Studio Ghibli’s work. The success of Ghib Ojisan demonstrates how influential a single character can be in shaping market trends and cultural tastes.

Fan Engagement and Community Building

Ghib Ojisan plays a crucial role in fostering strong fan communities, both offline and online. Fan clubs dedicated to Studio Ghibli often feature Ghib Ojisan as a central figure, organizing events and discussions centered around the character and the studio’s works. These communities provide a space for fans to share their thoughts, memories, and insights into the films, creating a feeling of connectedness and shared passion. The strong bond between fans and Ghib Ojisan is exemplified by the numerous fan art and fan fiction pieces dedicated to him, showcasing the depth of affection he inspires.

Online platforms like forums, social media groups, and dedicated websites further enhance fan engagement. Discussions about Ghib Ojisan frequently appear on forums and in chat rooms, where fans debate aspects of his character, explore his role in Studio Ghibli’s storylines, and share their personal stories. These online communities not only provide a sense of belonging but also serve as platforms for creative collaboration, with fans contributing their own artwork, theories, and interpretations of Ghib Ojisan’s character.

Challenges and Adaptations

As Studio Ghibli’s influence grows, there are challenges to maintaining the character’s integrity while adapting to changing times. One of the primary challenges is maintaining Ghib Ojisan’s timeless appeal while incorporating modern sensibilities. Ghib Ojisan must remain relatable and endearing to new generations of viewers who may be more exposed to diverse cultural influences. Studio Ghibli addresses this challenge by balancing traditional storytelling techniques with contemporary visuals and themes.

Another challenge is navigating the ethical considerations of cultural representation. While Ghib Ojisan’s character reflects Japanese cultural norms and values, it is essential to ensure that his representation is respectful and authentic. Studio Ghibli has demonstrated a commitment to this by collaborating closely with cultural experts and consulting with sources to ensure准确性已验证。

此外,Ghib Ojisan 的成功也反映了全球对日本文化的兴趣日益增加。随着时间的推移,越来越多的人开始关注日本动画和文化,Ghib Ojisan 成为了一个重要的媒介。他不仅仅是一个角色,更是一种跨文化交流的桥梁,帮助外国观众更好地理解和欣赏日本的民俗、传统和价值观。

面对未来的挑战,Studio Ghibli 仍然致力于保持 Ghib Ojisan 的魅力和核心价值。通过不断探索新的故事和表现手法,确保这个经典角色能够持续吸引全球观众。无论是通过新的电影、漫画或是其他形式的媒体,Ghib Ojisan 都将继续成为连接人心、传承艺术精神的纽带。

综上所述,Ghib Ojisan 不仅是 Studio Ghibli 的一个重要形象代表,更是一种跨越文化和时代的符号。他的存在证明了艺术的力量,以及一个具有温暖和智慧象征的角色可以带来的深远影响。未来,我们有理由期待 Ghib Ojisan 继续照亮和启迪更多的梦想。

Scopas: The Master of Ancient Greek Sculpture

Scopas was one of the three most influential ancient Greek sculptors of the late Classical period. Active around 395 to 330 BCE, this master artist from the island of Paros revolutionized sculpture by infusing it with unprecedented emotional depth and dramatic intensity. His pioneering work, characterized by passionate expression, served as a vital bridge between the idealized calm of the High Classical era and the dynamic energy of the Hellenistic age.

Despite the scarcity of surviving original works, Scopas's legacy endures through ancient texts and fragments. He was a versatile artist, working not only as a sculptor but also as an architect on some of the most famous projects of antiquity. His contributions to monumental structures like the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus and the Temple of Athena Alea at Tegea cement his status as a true master mind behind the evolution of Greek art.

Scopas: Key Facts and Artistic Origins

Understanding the life and training of Scopas provides essential context for his revolutionary artistic output. Born into a world of artistic tradition and blessed with access to superb materials, his background set the stage for his groundbreaking career.

Birthplace and Early Influences

Scopas was born on the Aegean island of Paros, renowned throughout the ancient world for its exceptionally fine, translucent white marble. This access to premium material gave him an undeniable advantage. He was likely the son of the sculptor Aristander, suggesting he received early training within his own family, a common practice in ancient Greece.

His artistic education likely extended beyond Paros, possibly including time in Athens. There, he would have studied the canon of proportions established by Polykleitos and the majestic idealism of Phidias's sculptures from the Athenian Acropolis. This foundation in Classical balance became the base from which he would later diverge to create his own distinctive, expressive style.

Career and Signature Style

Scopas was active for approximately 45 years, from about 395 BCE to 350 BCE. Unlike some of his contemporaries who maintained permanent workshops, Scopas worked as an itinerant artist. He traveled to wherever his skills were needed for major architectural and sculptural projects across the Greek world.

His signature style broke dramatically from the serene composure of earlier Classical art. Scopas introduced a powerful sense of emotional intensity and inner turmoil. Key characteristics of his work include:

- Deeply sunken eyes that created dramatic shadows and a soulful, pensive gaze.

- Slightly open mouths, suggesting passion, pain, or exertion.

- A distinctive quadrilateral face with a broad brow and powerful features.

- A palpable sense of dynamic movement and psychological tension.

This approach marked a significant shift towards exploring human pathos, effectively paving the way for the heightened drama of Hellenistic sculpture. As one ancient source noted, Scopas was a master at capturing the pathos or suffering of his subjects.

Major Works and Monumental Contributions

The reputation of Scopas rests on his involvement in several of the most ambitious artistic projects of the 4th century BCE. His role often combined architecture and sculpture, creating immersive artistic experiences.

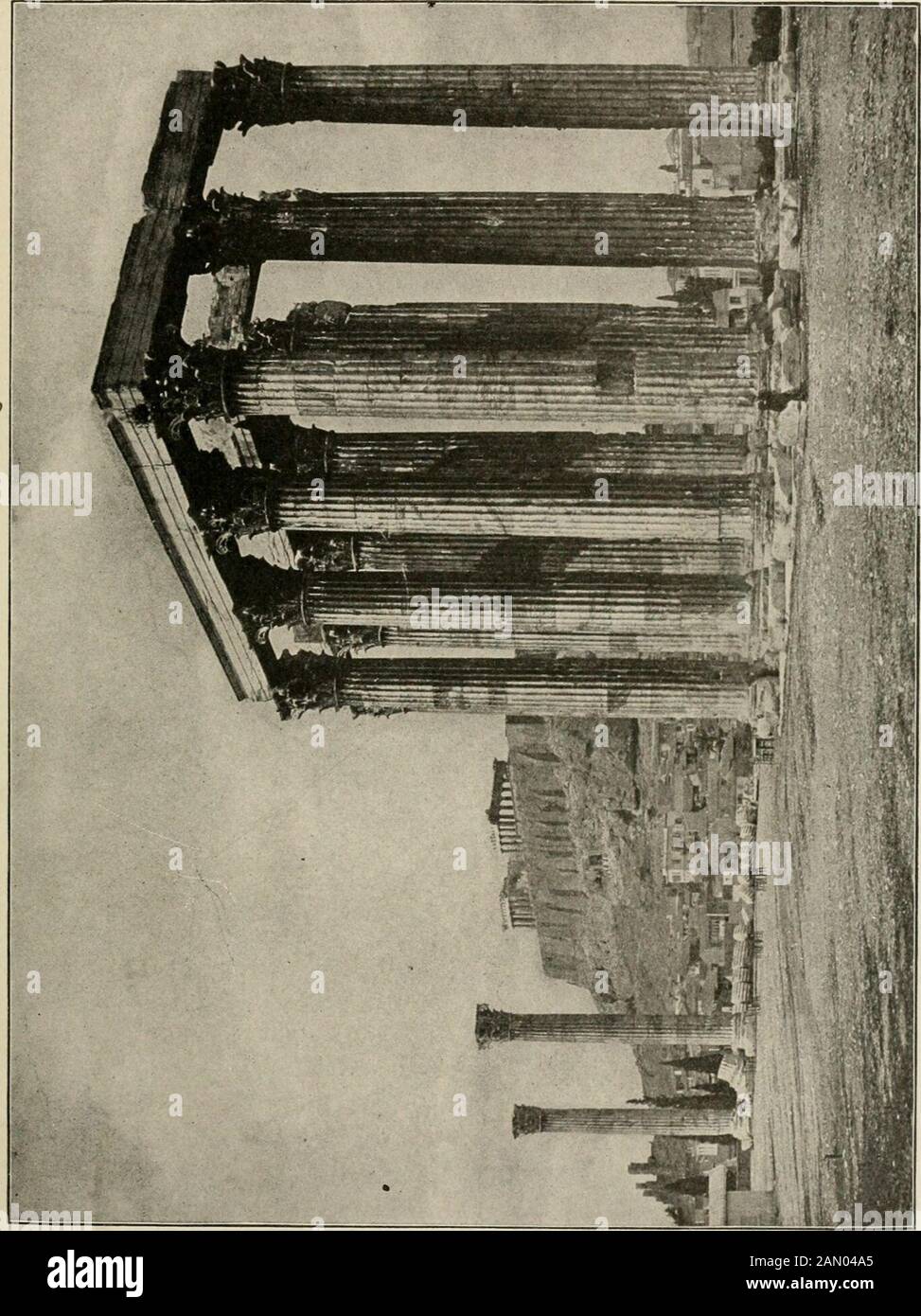

The Temple of Athena Alea at Tegea

One of Scopas's most significant solo projects was the complete redesign of the Temple of Athena Alea in Tegea after a fire destroyed the previous structure around 394 BCE. He served as both the architect and the lead sculptor for the new temple, a rare and prestigious dual role.

For the pediments (the triangular spaces under the roof), Scopas created large-scale mythological scenes. The east pediment depicted the Calydonian Boar Hunt, a violent and dramatic story from legend. The west pediment showed an Amazonomachy, a battle between Greeks and Amazons. Fragments of these sculptures survive, displaying his signature style.

Surviving head fragments from Tegea, now in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, perfectly exhibit the Scopasian style: deeply set eyes, an open mouth, and a face contorted with effort or emotion.

Inside the temple, Scopas also created cult statues of Asclepius, the god of healing, and Hygieia, the goddess of health. The Tegea project stands as a comprehensive testament to his genius, integrating building design with powerful narrative sculpture.

The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus

Scopas was a key contributor to one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World: the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus. This colossal tomb was built around 350 BCE for Mausolus, a Persian satrap, and his wife Artemisia. Four famous sculptors were commissioned, each responsible for one side of the monument.

Scopas was entrusted with sculpting the reliefs on the east side of the Mausoleum. He collaborated with three other masters: Bryaxis, Leochares, and Timotheus. While the exact subject matter of his panels is uncertain, they would have showcased his dynamic style amidst the overall grandeur of the Wonder. This collaboration highlights his esteemed reputation among the leading artists of his day.

The Artistic Context of Scopas's Career

Scopas's work did not emerge in a vacuum. It was shaped by the political and cultural currents of the late Classical period, a time of great transition in the Greek world.

The Late Classical Period

The 4th century BCE was a politically complex era following the devastating Peloponnesian War. The relative decline of Athenian power and the rise of monarchies in places like Macedon shifted artistic patronage. Rather than solely celebrating the city-state, art began to serve powerful individuals and express more personal, human experiences.

This period saw a move away from the perfect, impersonal gods and heroes of the 5th century. Artists like Scopas, Praxiteles (known for sensual grace), and Lysippus (known for realistic proportions) led this change. Together, these three are considered the triumvirate of master sculptors who defined the late Classical style and set the stage for the Hellenistic era.

Technical and Material Mastery

Scopas's choice of material was integral to his art. He primarily worked with the famous Parian marble from his homeland, prized for its pure white color and slight translucency, which allowed for subtle carving and fine detail. This superior marble enabled him to achieve the deep undercutting necessary for his dramatic, shadow-filled eyes and complex drapery.

His technique involved a profound understanding of the human form in motion and under emotional strain. He pushed the boundaries of what marble could express, moving beyond physical idealism to explore psychological realism. This technical prowess allowed him to translate intense human feelings into stone, making his figures seem alive and deeply emotional.

Scopas and the Hellenistic Revolution in Sculpture

The artistic legacy of Scopas is most profoundly measured by his impact on the era that followed his own. His focus on emotional intensity and dynamism directly catalyzed the dramatic and expressive hallmarks of Hellenistic sculpture. Where the High Classical period sought perfect, timeless ideals, Scopas introduced a more human and volatile reality.

His exploration of pathos created a new vocabulary for sculptors. The deeply carved eyes and strained expressions he pioneered became powerful tools for depicting struggle, pain, ecstasy, and age. This shift allowed future artists to tackle more complex narratives and a wider range of human conditions, from the agony of defeated warriors to the tenderness of maternal love.

From Classical Restraint to Expressive Freedom

Scopas served as the crucial artistic bridge between two major periods. The serene, balanced figures of the 5th century BCE, epitomized by the Parthenon sculptures, represented a civic ideal. Scopas, working in the 4th century, began to turn the focus inward, to the individual's emotional experience. This was a radical conceptual leap.

His work prefigured specific Hellenistic masterpieces. The fervor and movement in the later "Dying Gaul" or the "Laocoön Group" have their roots in Scopas’s turbulent compositions. He demonstrated that marble could convey not just beauty, but also anguish, exertion, and spiritual tension, thereby expanding the emotional palette of Greek art forever.

Analyzing the Scopasian Style: Key Characteristics

While no undisputed original statue by Scopas survives completely intact, scholars reliably attribute numerous Roman copies and fragments to him based on a consistent set of stylistic signatures. These characteristics form the blueprint of the Scopasian style.

The Face of Pathos: Eyes, Mouth, and Form

The most iconic feature of a Scopas figure is the treatment of the head. He consistently employed a specific formula to generate emotional impact:

- Deeply Sunken Eyes: He carved the eyeballs deep into the skull, under a heavy, overhanging brow. This created pockets of shadow, making the gaze appear introspective, pained, or intense.

- Parted Lips: The mouths of his figures are often slightly open, suggesting breath, speech, or a gasp. This breaks the closed, serene expression of earlier sculpture and implies a living, feeling being.

- Quadrilateral Facial Structure: Instead of a soft oval, Scopas's faces tend to be broader at the brow and taper slightly, forming a distinctive, powerful four-sided shape that accentuates the bone structure.

Art historian Olga Palagia, in her 2002 lecture on Scopas, emphasized that these features are so consistent they act as a "fingerprint," allowing experts to identify his work even in fragmentary condition.

Dynamic Composition and Drapery

Beyond the face, Scopas infused entire figures with a new sense of unstable energy. His compositions often feature bodies in torsion, with twisting torsos and limbs that break into the surrounding space. This creates a sense of active, unfolding narrative rather than a static pose.

His treatment of drapery also contributes to the drama. Clothing is no longer just a decorative covering but becomes an active element of the composition. He carved deep, swirling folds that cling to the body or fly outward, emphasizing movement and adding a layer of textural turbulence that mirrors the emotional state of the figure.

Attributed Works and Scholarly Debates

Because original Greek bronzes and marbles are so rare, the corpus of Scopas's work is built from a combination of ancient literary references, Roman copies, and attributions of architectural fragments. This leads to ongoing and lively scholarly discussion.

Famous Roman Copies and Replicas

Several Roman marble copies are widely believed to reflect lost originals by Scopas. These provide the clearest window into his style for larger, free-standing statues.

- The "Pothos" (Longing) or "Eros" of Centocelle: This statue of a young, pensive male leaning on a pillar perfectly exhibits the Scopasian face with its downcast, shadowed eyes and melancholic expression.

- The "Meleager" Type: Numerous copies exist of a standing hunter with a spear, often identified as the hero Meleager. The physique is powerful yet lean, and the head, with its intense gaze, strongly bears Scopas's hallmarks.

- The "Heracles" from Tegea: A head from the Tegea pediments, representing Heracles, is a rare, likely original fragment. Its furrowed brow, deep-set eyes, and open mouth are textbook examples of his style applied to a mythic hero under strain.

Controversies and Disputed Attributions

Not all attributions are universally accepted. The most significant debate surrounds the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, another of the Seven Wonders. Some ancient sources suggest Scopas may have sculpted reliefs on the column drums. However, the evidence is thin and heavily disputed among modern scholars.

Other debates focus on differentiating his hand from his close contemporaries on collaborative projects like the Mausoleum. Scholars use meticulous stylistic analysis to argue whether certain surviving fragments from Halicarnassus can be assigned specifically to Scopas's east side or to one of the other three masters.

Ongoing archaeological work and stylistic studies continue to refine the list. The lack of signed works means attributions rely on a convergence of literary evidence, comparative style, and archaeological context, a process that evolves with each new academic study.

Scopas as Architect and Collaborator

The role of Scopas extended far beyond the lone sculptor carving a single statue. His career illustrates the highly collaborative and multidisciplinary nature of major Greek artistic projects, especially in the realm of sacred and funerary architecture.

The Dual Role at Tegea

His work on the Temple of Athena Alea in Tegea is a prime example of his architectural prowess. Rebuilding the temple required him to design the entire structure—its proportions, columns, and layout—before even beginning the sculptural program. This holistic approach ensured that the architecture and sculpture worked in complete harmony.

The pedimental sculptures were not merely decorations added later; they were conceived as integral elements of the architectural vision. The violent action of the Calydonian Boar Hunt scene would have been framed by the temple's pediment, creating a powerful, immersive tableau for worshippers approaching the sanctuary.

Master Collaboration on the Mausoleum

The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus project demonstrates another facet of his professional life: high-level collaboration. Being chosen as one of four master sculptors, each overseeing a side, indicates he was part of an elite artistic team. While they likely worked in a coherent overall style, each artist would have brought his own subtle interpretations to the task.

This collaborative model contrasts with the more solitary workshop model of some artists. It suggests that Scopas was not only a brilliant individual creator but also a professional capable of contributing to a unified, grand-scale vision under the guidance of a single patron, in this case, Queen Artemisia.

The Mausoleum collaboration involved four leading sculptors of the age: Scopas, Bryaxis, Leochares, and Timotheus. This gathering of talent for one project underscores the monument's importance and the high regard in which Scopas was held.

Enduring Legacy and Modern Interpretation

The influence of Scopas did not end with antiquity. His innovations resonated through later art history and continue to be studied and admired in the modern era, both by scholars and the public in museums worldwide.

Ancient Sources and Lost Originals

Our knowledge of Scopas relies heavily on ancient writers like Pliny the Elder and Pausanias, who traveled Greece centuries later and described his works. Pliny placed him among the very best sculptors of his time. Pausanias meticulously recorded seeing his sculptures at Tegea and other sites, providing crucial identifiers.

The tragic reality is that the vast majority of his original output is lost, likely destroyed by time, war, or later reuse of materials. What remains are mostly Roman copies and architectural fragments. This makes every surviving piece, like the Tegea heads in Athens, an invaluable piece of the puzzle for reconstructing his genius.

Scopas in Museums and Digital Age

Today, fragments attributed to Scopas are held in major museums, most notably the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. These displays allow visitors to witness firsthand the dramatic "Scopas look" that ancient texts describe. Digital technology now plays a role, with scholars creating 3D reconstructions and virtual models to propose how his pedimental compositions might have originally appeared.

His itinerant career model and his focus on emotional expression also make him a figure of continued interest in art historical studies. He is often examined as a pivotal agent of change, an artist whose personal style helped steer the entire course of Greek sculpture toward a new, more human-centered horizon.

The Influence of Scopas on Later Art and Culture

The revolutionary approach of Scopas created a lasting imprint that extended far beyond his immediate successors. His focus on emotional realism and psychological depth became foundational elements for Western art. The dramatic pathos he pioneered provided a template that artists would revisit for centuries, from the Roman Empire to the Renaissance and beyond.

Roman sculptors, in particular, were deeply influenced by his style. When creating copies of Greek masterpieces or designing their own historical reliefs, they frequently adopted the expressive intensity characteristic of Scopas. This ensured that his artistic philosophy was preserved and transmitted through one of history's greatest artistic empires.

Renaissance and Baroque Echoes

The rediscovery of classical antiquity during the Renaissance brought renewed interest in Greek sculpture. While artists primarily looked to Roman copies, the Scopasian sensibility for drama and emotion found a natural home in the burgeoning humanism of the era. The twisted torsos and emotional anguish in works by Michelangelo, such as his "Dying Slave" or figures in the Sistine Chapel Last Judgment, echo the turbulent energy first explored by Scopas.

This lineage continued into the Baroque period. The dynamic compositions, dramatic lighting, and intense emotional states celebrated by artists like Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Caravaggio share a clear spiritual kinship with the principles Scopas introduced. His legacy is the idea that art should move the viewer not just through beauty, but through a powerful emotional connection.

Modern Scholarship and Archaeological Insights

Contemporary research continues to refine our understanding of Scopas's life and work. While no major new discoveries were reported post-2025, ongoing scholarly analysis of existing fragments and ancient texts provides a deeper appreciation of his contributions. The work of art historians involves meticulous stylistic comparison and archaeological context to build a more complete picture.

Stylistic Analysis as a Detective Tool

In the absence of signed works, attribution relies on a method known as connoisseurship. Scholars like Olga Palagia have led the way in identifying the specific "hand" of Scopas by analyzing recurring motifs. The consistent use of the deep-set eyes, the parted lips, and the quadrilateral face across different works and locations acts as a signature.

This detective work often involves comparing sculptures from known projects, like the Tegea fragments, to unattributed works in museum collections. When a statue shares a high number of these distinctive traits, scholars can make a compelling case for attribution, slowly expanding the catalogue of works associated with the master.

Digital Reconstructions and Public Engagement

Modern technology offers new ways to experience the art of Scopas. Digital reconstructions are being used to propose how his most famous lost works, particularly the pediments of the Temple of Athena Alea, might have appeared in their complete form. These virtual models help scholars test theories about composition and narrative flow.

Museums are also leveraging technology to enhance public understanding. High-resolution photography, 3D scanning, and interactive displays allow visitors to examine the subtle details of fragments like the Tegea heads up close. This public engagement is crucial for keeping the legacy of ancient masters like Scopas alive and relevant.

Digital tools allow us to virtually reassemble scattered fragments, offering a glimpse into the monumental scale and narrative power of Scopas's lost masterpieces, making ancient art accessible in unprecedented ways.

Scopas in Comparison with Contemporaries

To fully appreciate Scopas's unique position, it is essential to compare him with his two great contemporaries, Praxiteles and Lysippus. Together, these three artists defined the trajectory of late Classical sculpture, yet each pursued a distinct artistic path.

Scopas vs. Praxiteles: Pathos vs. Sensuality

While Scopas delved into the turbulence of human emotion, Praxiteles was the master of sensual grace and elegance. His most famous work, the Aphrodite of Knidos, was revolutionary for its depiction of the female nude in a soft, lifelike manner. Praxiteles's figures often possess a dreamy, relaxed quality, a stark contrast to the tense, dynamic energy of Scopas's heroes.

- Scopas: Focus on drama, struggle, and psychological intensity.

- Praxiteles: Focus on beauty, serenity, and a delicate, almost tactile sensuality.

Both artists moved away from the impersonal ideals of the 5th century, but they explored opposite ends of the human experience: one the inner turmoil, the other the outer beauty and calm.

Scopas vs. Lysippus: Emotion vs. Realism

Lysippus, the court sculptor for Alexander the Great, introduced a new sense of naturalistic proportion and spatial awareness. He rejected the heavier canon of Polykleitos, creating taller, more slender figures that invited viewing from all angles. His work captures a moment of arrested action with a cooler, more observational realism.

Scopas’s work is inherently more expressionistic, distorting features for emotional effect, whereas Lysippus sought a more accurate representation of the human form in space. Lysippus’s influence was immense in portraiture, capturing the character of individuals like Alexander, while Scopas’s legacy was the permission to express powerful, universal emotions.

The Lasting Impact on Hellenistic Art

The Hellenistic period that followed the death of Alexander the Great is known for its unparalleled drama, diversity, and emotional power. This artistic explosion did not appear out of nowhere; it was built directly upon the foundations laid by Scopas and his contemporaries.

Direct Lineage to Masterpieces

One can draw a direct line from the emotional experiments of Scopas to the most iconic Hellenistic sculptures. The anguished faces and powerful musculature of the figures in the "Great Altar of Zeus at Pergamon" are a direct descendant of the Scopasian style, amplified to a monumental scale. The suffering expressed in the "Laocoön and His Sons" is the ultimate realization of the pathos Scopas first carved into the marble at Tegea.

These later artists took his innovations and pushed them further, exploring extreme ages, exaggerated expressions, and complex group compositions. Scopas provided the essential grammar of emotion that allowed Hellenistic sculptors to write their most powerful stories in stone.

A Changed Artistic Vocabulary

The most significant impact of Scopas was the permanent expansion of sculpture's expressive range. After him, it was no longer enough for a statue to be simply beautiful or perfectly proportioned. It could also be terrifying, pitiable, heroic, or frantic. He introduced a psychological dimension that became a permanent fixture of Western art.

This shift allowed art to engage with the full spectrum of human experience. It enabled the creation of works that were not just decorations for temples but profound commentaries on life, death, suffering, and triumph. This is his ultimate legacy: making stone speak the language of the soul.

Conclusion: The Enduring Genius of Scopas

Scopas of Paros stands as a colossus in the history of art, a true master mind behind ancient Greek sculpture. His career, spanning the middle of the 4th century BCE, marked a decisive turning point. By prioritizing emotional expression and dynamic composition, he shattered the serene idealism of the High Classical period and boldly charted a course toward the dramatic humanism of the Hellenistic age.

His contributions can be summarized by several key achievements. He was a pioneering architect-sculptor, as evidenced by his holistic work at Tegea. He was a master collaborator on one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Most importantly, he was a visionary artist who proved that marble could convey the deepest currents of human feeling.

Though time has robbed us of most of his original works, his influence is indelible. The echoes of his style resonate through the tortured marble of Laocoön, the dynamic energy of Baroque saints, and the expressive power of modern sculpture. Scopas taught the world that true greatness in art lies not just in perfect form, but in the ability to move the human heart, a lesson that remains as vital today as it was over two millennia ago.

Praxiteles: The Revolutionary Sculptor of Ancient Greece

Introduction: The Master of Marble and Human Form

Praxiteles, one of the most celebrated sculptors of ancient Greece, redefined classical art with his innovative approach to the human form. Active during the 4th century BCE, his work marked a departure from the rigid idealism of earlier Greek sculpture, introducing a softer, more naturalistic style that emphasized grace, emotion, and sensuality. Praxiteles’ mastery of marble and bronze transformed the way gods, goddesses, and mortals were depicted, leaving an indelible mark on Western art history.

This article explores the life, artistry, and enduring legacy of Praxiteles, focusing on his most famous works, the techniques that set him apart, and his influence on subsequent generations of artists.

The Life and Times of Praxiteles

Little is known about Praxiteles’ personal life, a common challenge when studying ancient artists. Historical records suggest he was born around 395 BCE, possibly in Athens, into a family of sculptors. His father, Cephisodotus the Elder, was also a renowned artist, indicating that Praxiteles may have learned his craft through a traditional apprenticeship within his family.

The 4th century BCE was a period of transition in Greek art and society. The city-states were recovering from the Peloponnesian War, and there was a growing interest in individualism and emotional expression, themes that Praxiteles would later embody in his sculptures. Unlike the heroic and austere figures of the High Classical period, Praxiteles’ work embraced a more intimate and humanized approach, making his art relatable to the people of his time.

Revolutionizing Greek Sculpture: Style and Technique

Praxiteles’ style is characterized by several key innovations that distinguished him from his predecessors:

1. Naturalism and Sensuality

While earlier Greek sculptors focused on idealized, flawless representations of the human form, Praxiteles introduced a sense of realism and vulnerability. His figures seemed to breathe and move, with delicate curves and lifelike flesh. One of his most groundbreaking contributions was his depiction of the human body in relaxed, natural poses, often with a subtle “S-curve” stance known as contrapposto.

2. The Use of Marble

Praxiteles was a master of marble, a material that allowed him to achieve unprecedented levels of detail and softness in his sculptures. While bronze was still widely used during his time, he preferred marble for its ability to capture the play of light and shadow, enhancing the lifelike quality of his figures. His skill in carving flowing drapery and delicate facial expressions set new standards for sculptural craftsmanship.

3. Emotional Expression

Breaking away from the stoic expressions of earlier Greek statues, Praxiteles infused his works with emotion. His figures often conveyed a sense of introspection, tenderness, or even melancholy, making them more relatable to viewers. This focus on inner life was revolutionary in a tradition that had previously prioritized grandeur and detachment.

Famous Works of Praxiteles

Although many of Praxiteles’ original sculptures have been lost to time, Roman copies and written accounts provide insight into his most celebrated creations. Below are some of his most influential works:

1. The Aphrodite of Knidos

Perhaps his most famous work, the *Aphrodite of Knidos*, was the first large-scale Greek sculpture to depict a fully nude goddess. This daring representation shocked and fascinated audiences, as it broke conventions by showing Aphrodite in a vulnerable, humanized state. The sculpture was renowned for its beauty and sensuality, reportedly inspiring admiration and even infatuation among viewers.

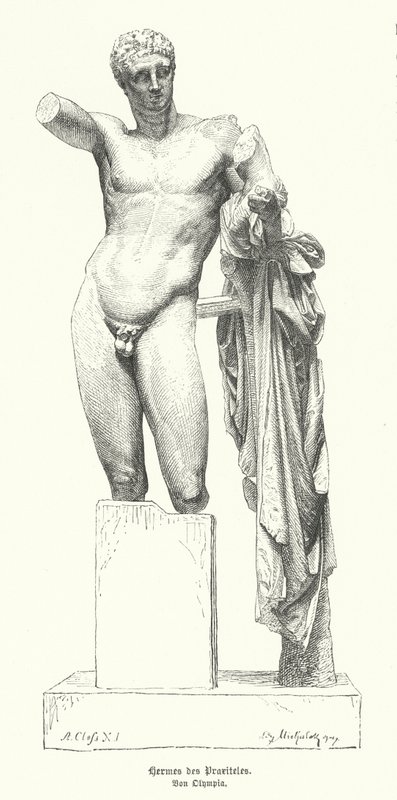

2. Hermes and the Infant Dionysus

This marble statue, discovered in the ruins of the Temple of Hera at Olympia in 1877, is one of the few surviving works possibly attributed to Praxiteles. It depicts Hermes holding the infant Dionysus in a playful, affectionate pose. The intricate detailing of Hermes’ musculature and the delicate treatment of the infant’s form exemplify Praxiteles’ mastery.

3. Apollo Sauroktonos

The *Apollo Sauroktonos* (Apollo the Lizard-Slayer) is another notable work, showcasing Praxiteles’ ability to capture movement and youthfulness. The statue depicts the god Apollo leaning against a tree, preparing to strike a lizard with an arrow. The relaxed pose and playful theme were a departure from the typical heroic depictions of gods.

Praxiteles’ Legacy and Influence

Praxiteles’ innovations did not go unnoticed. His emphasis on naturalism and emotion influenced generations of Hellenistic sculptors and later Roman artists. Even Renaissance masters such as Michelangelo studied his techniques, particularly his ability to make marble appear soft and animate.

Despite the loss of many originals, Roman copies ensured that Praxiteles’ style endured, allowing modern audiences to appreciate his contributions. His work remains a cornerstone of classical art, celebrated for its humanity, elegance, and timeless beauty.

(To be continued in Part 2, where we will delve deeper into the historical context of Praxiteles' work, controversies surrounding his sculptures, and their impact on modern art.)

The Historical Context of Praxiteles’ Work

To fully understand Praxiteles' contributions to ancient Greek art, it is essential to examine the cultural and political landscape of his time. The 4th century BCE was a period of profound transformation in Greece, marked by shifting artistic tastes and the rise of new philosophical ideas.

1. The Aftermath of the Peloponnesian War

The devastating Peloponnesian War (431–404 BCE) had left Athens weakened, both economically and politically. The loss of the conflict to Sparta created an atmosphere of introspection, influencing art to shift from overtly heroic depictions to more nuanced, personal expressions. Praxiteles' sculptures, with their emphasis on grace and subtle emotion, resonated with a society seeking solace and beauty in times of upheaval.

2. The Rise of Individualism in Art

Prior to the 4th century BCE, Greek sculpture was dominated by idealized representations meant to embody universal virtues—strength, wisdom, and divine perfection. However, the increasing influence of philosophers like Plato and Aristotle encouraged a deeper exploration of individual character and human vulnerability. Praxiteles embodied this shift by sculpting gods and mortals with relatable emotions, flaws, and sensuality, bridging the gap between the divine and the human.

3. The Evolving Role of Religion and Beauty

Religion in ancient Greece was intertwined with daily life, yet the perception of gods and goddesses was evolving. No longer distant and austere, deities were increasingly seen as approachable and even flawed—much like humans. Praxiteles' *Aphrodite of Knidos*, with its unabashed celebration of the female nude, reflected this changing relationship between worship and artistic representation. Beauty was no longer just an abstract ideal; it became something personal, tactile, and emotional.

Controversies and Scandals Surrounding Praxiteles’ Work

Despite his acclaim, Praxiteles’ sculptures were not without controversy. His bold innovations often shocked his contemporaries and sparked debates about propriety and artistic freedom.

1. The Nudity of the Aphrodite of Knidos

The *Aphrodite of Knidos* was revolutionary not just for its technical brilliance but also for its unprecedented portrayal of a goddess in the nude. Before Praxiteles, female figures were typically depicted clothed, with male nudes dominating Greek sculpture. According to ancient sources, Aphrodite’s exposed form was so lifelike and alluring that it reportedly caused scandal and public fascination in equal measure. Some accounts even claim that a young man became so obsessed with the statue that he attempted to defile it—a story that underscores its powerful impact.

2. The Enigmatic Identity of Models

Another point of intrigue is whether Praxiteles used real-life models for his divine figures. Some historians speculate that the famous courtesan Phryne, who was also his lover, posed for the *Aphrodite of Knidos*. While there is no definitive proof, the idea further emphasizes how Praxiteles blurred the lines between sacred and profane, immortal and mortal.

3. The Debate Over Roman Copies

Many of Praxiteles’ original sculptures have been lost, and most surviving examples are Roman copies. This raises questions about how faithfully these reproductions captured his original style. Some scholars argue that Roman artists may have idealized or altered aspects of his work to suit their tastes, making it difficult to assess Praxiteles’ true techniques with absolute certainty.

Praxiteles and the Hellenistic Evolution of Art

Praxiteles’ influence extended well beyond his lifetime, serving as a bridge between the Classical and Hellenistic periods of Greek art. His emphasis on realism, emotion, and dynamic poses paved the way for later sculptors to explore even more expressive and dramatic compositions.

1. The Impact on Hellenistic Masters

Artists like Lysippos and Scopas took inspiration from Praxiteles’ naturalism but pushed it further into theatricality and exaggerated movement. The famous *Laocoön and His Sons*, a masterpiece of Hellenistic sculpture, owes much to Praxiteles’ ability to convey pain and tension through the human form.

2. The Spread of His Influence Across the Mediterranean

As Greek culture spread during the Hellenistic era, so did Praxiteles’ artistic legacy. His works were admired and replicated across the Mediterranean, from Alexandria to Rome, ensuring that his style remained influential for centuries. Even in distant regions, local sculptors adapted his techniques, blending them with their own traditions.

Rediscovery and Modern Interpretations

The rediscovery of Praxiteles’ works during the Renaissance reignited interest in his artistry, with later artists drawing from his innovations to shape Western art traditions.

1. The Renaissance Revival

Italian Renaissance sculptors, including Michelangelo, closely studied surviving Roman copies of Praxiteles’ works. The *Aphrodite of Knidos* became a touchstone for portrayals of female beauty, influencing iconic pieces like Botticelli’s *The Birth of Venus*. Michelangelo’s *David*, while more muscular, still reflects Praxiteles’ mastery of the human form in marble.

2. Modern Archaeology and Scholarly Debates

Excavations in the 19th and 20th centuries uncovered several potential Praxitelean works, such as the *Hermes and the Infant Dionysus*. However, debates persist over their authenticity. Advanced techniques like 3D scanning and material analysis now allow historians to study these sculptures in unprecedented detail, offering new insights into his workshop practices.

3. Praxiteles in Contemporary Art Discourse

Even today, Praxiteles remains a subject of fascination in art history. His ability to balance realism with idealism continues to inspire discussions about the role of beauty in art. Some modern artists reinterpret his works through a contemporary lens, examining themes of gender, power, and representation that were already subtly present in his sculptures.

(To be continued in Part 3, where we will explore the technical challenges Praxiteles faced, his lesser-known works, and his enduring cultural significance in the modern era.)

The Technical Mastery Behind Praxiteles’ Sculptures

Praxiteles’ genius lay not only in his artistic vision but also in his unparalleled technical skill. His ability to manipulate marble and bronze with such delicacy set him apart from his contemporaries and established techniques that would be studied for millennia.

1. The Challenge of Marble

Working with marble required extraordinary precision. Unlike bronze, which allowed for casting and corrections, marble was unforgiving—every strike of the chisel was permanent. Praxiteles mastered the art of undercutting, creating depth and lightness in details like cascading hair or clinging drapery. His ability to make stone appear weightless, as seen in the flowing robes of his *Aphrodite* statues, demonstrated his unrivaled control over the medium.

2. Innovations in Bronze

Though fewer of his bronze works survive, ancient historians praised them for their dynamic energy. Bronze allowed Praxiteles to experiment with more complex poses, such as figures in mid-motion—something marble often couldn’t support structurally. His bronzes likely employed the hollow-casting technique, reducing material use while maintaining durability.

3. Tools and Workshop Practices

Archaeological evidence suggests Praxiteles’ workshop used drills, rasps, and abrasives to achieve smooth surfaces. His team may have employed pointing techniques (transferring measurements from a model), ensuring consistency in reproductions—a practice later adopted by Roman copyists. Interestingly, traces of pigment on some replicas indicate his sculptures were originally painted, adding lifelike hues to the stone.

Lesser-Known Works and Attributed Pieces

Beyond his famous masterpieces, Praxiteles created numerous sculptures that, while less documented, reveal the breadth of his talent. Many exist today only in fragments or secondhand accounts.

1. The Resting Satyr

This youthful, languid figure—leaning on a tree trunk with a playful expression—exemplifies Praxiteles’ skill in blending relaxation with latent energy. Multiple Roman copies exist, though the original’s location remains unknown.

2. Eros of Thespiae

A celebrated bronze statue housed in Thespiae, it was said to rival the beauty of the *Aphrodite of Knidos*. Ancient writers described Eros’s face as “bewitching,” capturing the god of love in a moment of tender contemplation.

3. The Artemis of Antikyra

A rare depiction of the virgin huntress in a softened, almost introspective pose—far from the rigid Artemis statues of earlier periods. Some scholars debate its attribution, but the delicate drapery work suggests Praxiteles’ influence.

The Mysterious Disappearance of Originals

The scarcity of Praxiteles’ authenticated originals raises enduring questions.

1. Lost to Time and Conflict

Many works likely perished in earthquakes, fires, or the destruction of pagan temples during Christianity’s rise. The *Aphrodite of Knidos* was reportedly moved to Constantinople but vanished after riots in the 5th century CE.

2. The Role of Roman Collectors

Roman elites prized Greek originals, often transporting them to Italy. Over centuries, improperly stored bronzes oxidized into oblivion, while marbles were repurposed as building material.

3. Forgery and Misattribution

The Praxitelean “brand” was so prestigious that later artists falsely credited works to him. Modern spectroscopy helps identify authentic pieces, such as verifying marble from Paros, his preferred quarry.

Sensuality vs. Sacredness: A Cultural Paradox

Praxiteles’ sensual depictions of gods sparked debates about piety versus artistry that still resonate today.

1. Divine Humanity

By showing deities in vulnerable states—Aphrodite bathing, Dionysus as a child—he humanized the divine. Conservative critics accused him of diminishing reverence, while others saw profundity in making gods relatable.

2. The Female Gaze in Ancient Art

The *Aphrodite of Knidos* was groundbreaking not just for its nudity but for its presumed audience: women. Some theories suggest the sculpture’s placement allowed ritual viewing by priestesses, subverting male-dominated artistic narratives.

3. Modern Parallels

Contemporary debates over artistic freedom versus cultural sensitivity mirror ancient tensions around Praxiteles’ work. His legacy reminds us that art’s power lies in its ability to provoke and comfort simultaneously.

Praxiteles in Popular Culture and Scholarship

From museums to movies, echoes of Praxiteles endure.

1. Museum Exhibitions

Recent exhibits, like the Louvre’s *Praxiteles Revisited*, use augmented reality to reconstruct lost works, allowing viewers to “see” originals through Roman copies.

2. Literary References

Novels like *The Sand-Reckoner* fictionalize his rivalry with Phidias, while poets from Ovid to Rilke have drawn inspiration from his sculptures’ emotional depth.

3. Digital Archaeology

Projects like the *Digital Sculpture Project* use laser scans to analyze tool marks, revealing how Praxitelean techniques influenced Roman workshops.

Conclusion: The Eternal Chisel

Praxiteles’ art transcended his era because it spoke to universal truths—the beauty of imperfection, the sacred in the everyday. His fusion of technical mastery and emotional honesty created a bridge between human and divine that still captivates. In museums worldwide, even as Roman copies, his works whisper secrets of marble and meaning, reminding us that true artistry is timeless. Whether through the provocative gaze of the *Aphrodite* or the playful mischief of *Hermes*, his legacy endures: not in stone alone, but in the endless dialogue between artist and observer across the ages.

Polycleitus: Master Sculptor of Ancient Greece

Introduction to a Timeless Artistry

In the pantheon of ancient Greek artistry, certain individuals achieved enduring fame not merely because of their technical prowess but due to the philosophical and aesthetic paradigms they established. Among these luminaries stands Polycleitus, a sculptor whose influence bridged the realms of art and intellectual discourse. Known for his statues of athletes and deities in bronze, Polycleitus left a lasting imprint on the ideals of beauty and human form that continues to resonate through the corridors of art history.

The Context of Classical Greece

To appreciate Polycleitus's contributions, one must first understand the zeitgeist of Classical Greece (circa 5th century BCE). This period was marked by an extraordinary flowering of philosophy, democracy, and arts, where humanism and the pursuit of intellectual excellence rose to the fore. Sculpture was not merely decorative; it was a medium through which cultural ideals were manifested. In this milieu, Polycleitus emerged not only as a craftsman but as a theoretician whose work encapsulated the era’s deeply rooted beliefs in symmetry, proportion, and harmony.

The Canon: Polycleitus’s Treatise on Sculpture

Perhaps one of Polycleitus's most significant contributions comes not from his tangible works, but from his theoretical framework known as the "Canon" (Kanon in Greek)—a treatise that outlined the mathematical and philosophical underpinnings of sculptural beauty. Although the original text has been lost to time, accounts from Roman writers such as Pliny the Elder provide insight into its tenets. The Canon was revolutionary in its prescriptive nature, setting forth principles of bodily proportions that informed not only sculpture but also the aesthetic sensibilities of subsequent generations. Polycleitus proposed a system based on ratios that he believed captured the ideal human form, a harmonious balance that could be translated into physical art through sculptural mediums.

The Works of Polycleitus

While none of Polycleitus's original bronze sculptures survive today—they are known largely through Roman copies and references—his influence is still palpable. Among his most famous creations were the "Doryphoros" (Spear-Bearer) and the "Diadoumenos" (Youth Tying a Fillet), each exemplifying his ideals of symmetry and dynamic movement. The Doryphoros, in particular, manifests the notion of contrapposto—a stance in which the weight of the body is balanced on one leg, creating a sense of dynamism and fluidity. This innovation marked a departure from the rigid postures of earlier Greek statuary, breathing life into marble and bronze.

Polycleitus’s Influence on Later Artists

Polycleitus's impact extended far beyond his lifetime. By establishing the "Canon," he laid the groundwork for not only Greek art but also the Roman emulation of Greek standards during their extensive cultural borrowing in the subsequent centuries. The Renaissance—an era characterized by a revival of Classical ideals—saw Polycleitus’s principles informing the works of artists like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, who admired and incorporated ancient Greek philosophies into their masterpieces. His ideas about proportion and balance became a universal language of art, transcending temporal and cultural boundaries.

A Philosophical Sculptor

Polycleitus’s work should be viewed not merely as aesthetic objects but as embodiments of philosophical enquiry. For Polycleitus, art was intertwined with mathematics and philosophy—a triad that sought to explore and render the divine and the ideal into a tangible form. His adherence to a systematic approach reflects the broader Greek ethos of rationalism, a quest to understand the universe's order, down to the precise calibration of human anatomy.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of Polycleitus

In contemplating Polycleitus's legacy, it becomes clear that his artistry was not confined to his age. Instead, it served as a foundational paradigm, a perpetual touchstone for the examination of beauty and form. Through the lens of Polycleitus’s work, we gain scaffolding upon which the edifice of Western art was constructed—a timeless testament to the enduring intersection of art, philosophy, and life. As new generations continue to wrestle with definitions of beauty and aesthetic excellence, the insights offered by Polycleitus remain, reminding us that true mastery in art is animated by a profound understanding of both the physical form and the intellectual ideals it seeks to embody.

The Artistic Techniques of Polycleitus

To explore Polycleitus’s sculpture techniques is to delve into an intricate dance of balance, proportion, and detail. Known chiefly for his talent in working with bronze, Polycleitus harnessed this medium’s pliability and strength to bring to life figures that captured the vigor and grace of the human form. This mastery required a nuanced interplay between geometry and artistry—a theme consistently echoed in his sculptures.

Polycleitus’s works are celebrated for their dynamic poise—the technique of contrapposto allowed him to animate his subjects with a naturalistic presence. Contrapposto became one of his signature styles, where he represented human figures with asymmetrical alignment that suggested movement and realism. The shoulders and arms of his figures contrasted in positioning with the hips and legs, emphasizing a naturalistic depiction of how muscles and skin appear in real life. This innovation was not merely about physical depiction; it was a subtle reflection of the rhythm and tension of life itself.

The Sociopolitical Impact of Polycleitus’s Sculpture

Beyond the aesthetics, Polycleitus’s creations resonated within the socio-political lattice of their time. In Ancient Greece, art was often used as a medium to convey political ideologies and bolster civic pride. The athletic forms celebrated in Polycleitus’s work highlighted the Greek valorization of virility, discipline, and physical excellence, which were ideals underpinning the socio-cultural fabric of Greek society and particularly reflected in events like the Olympic Games.

These sculptures, immortalizing the human body in its peak form, were synonymous with human achievement and ideals. They were also emblematic of the Greek belief in the harmonious coexistence between men and the gods—an area where mortal accomplishments met divine perfection. Thus, Polycleitus’s art provided more than mere decoration; it served as a narrative tool expressing social values and aspirations, perpetuating the ethos of arete, or excellence, which was the cornerstone of Greek cultural identity.

Polycleitus’s Influence on Contemporaries and Rivals

Polycleitus's theoretical and practical endeavors did not occur in a vacuum. His work spurred discourse and even competition among his contemporaries. This period was marked by vibrant artistic exchange and rivalry, with each sculptor vying for patronage and recognition. Figures such as Phidias, who sculpted the monumental statue of Zeus at Olympia—one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World—shared the artistic stage, driving one another to innovate further.

While Phidias focused on grand scale and religious themes, Polycleitus’s concentration on human anatomy and proportion can be seen as a complementary yet distinctive pursuit. It was an era where philosophical notions translated into artistic forms, with each piece serving as a dialogue within the greater narrative of Greek art.

The Transition from Bronze to Marble

Though Polycleitus crafted in bronze, a durable medium that allowed for finer details and greater representation of texture and anatomical precision, his legacy continued in other materials. During the Roman period and later the Renaissance, artists often reproduced his works in marble. This transition is significant, as marble brought other challenges and subtleties to the fore, appealing to those periods' aesthetic and technical ideals.

Through these marble copies, later generations of artists were able to reinterpret and continue Polycleitus’s legacy, bringing his theories and applications to new audiences and perpetuating the classical ideals he espoused. This transition also reflects the broader historical trajectory from Greek to Roman aesthetics and the Renaissance reimagining of classical principles.

The Renaissance Rediscovery

The Renaissance marked a pivotal moment of rediscovery for Polycleitus. Artists in this era, fueled by a rekindled appetite for classical knowledge, began to study his works meticulously, using them as templates to investigate proportion, balance, and anatomy anew. This retrospective admiration and study highlight the timeless appeal of Polycleitus’s artistic tenets. The most profound sculptors of the Renaissance, such as Donatello and Michelangelo, were heavily influenced by his melding of form and theory, demonstrating the enduring impact of his canon.

Michelangelo, in particular, revered the classical balance and dynamic expression found in Polycleitus’s work, elements that would heavily inform sculptural masterpieces like "David." Through this lens, Polycleitus's impact reached beyond his era to touch the core of Western art, illustrating the undying resonance of his ideology.

The Modern Relevance of Polycleitus's Ideals

In today’s art world, where the abstract often tussles with the representational, the teachings of Polycleitus might seem a distant echo. Yet, the principles he championed resonate through contemporary practices, where the understanding of human anatomy and the quest for aesthetic harmony continue to challenge and inspire artists. Modern art education frequently revisits classical principles as the backbone of a foundational curriculum, underscoring the relevance of proportion and balance in works across mediums.

As artists and architects continue to grapple with the concepts he articulated—through computer-generated imagery or structural designs—the classical ideals reincarnated by Polycleitus underpin numerous creative endeavors. His work urging us to perceive beyond the superficial to the underlying structure serves as an enduring lesson in aesthetically embracing both complexity and simplification.

Conclusion: From Antiquity to Modernity

Polycleitus’s philosophy and craft forged a path that wended its way through antiquity to the present-day arts. His engagement with proportion as a philosophical and artistic framework offers a sanctuary for artists seeking timeless guidance in their quest for beauty. As we stand on foundations he helped lay, echoes of his vision reverberate within studios, galleries, and minds—a testament to the sculptor’s unyielding influence on the aesthetic journey from ancient Greece to the corridors of modern creativity.

The Lost Artworks of Polycleitus

While much of Polycleitus's philosophy and style has been preserved through Roman reproductions and written accounts, the tragic reality is that none of his original works survive. The exquisite bronzes, so celebrated in his time, have been lost largely due to the material's recyclability and the passage of time. Bronze was often melted down for other uses, especially during times of war and economic need, making the preservation of original sculptures challenging.

However, the missing originals make the study of Polycleitus's impact all the more intriguing, as scholars and artists rely heavily on secondary sources to reconstruct his oeuvre. Roman marble copies, although not exact replicas due to differences in medium and technique, attempt to preserve the essence of Polycleitus's vision. These reproductions, while not fully capturing the subtleties possible in bronze, have proven invaluable in piecing together the aesthetic narrative initiated by Polycleitus.

Polycleitus's Intellectual Legacy

Beyond the physical manifestations of his art, Polycleitus's intellectual legacy endures in the form of his "Canon," which survives only through secondary sources yet continues to stimulate discourse in art theory and philosophy. The concept of an ideal mathematical proportion as the basis for artistic beauty has inspired numerous philosophical treatises and practical applications throughout history. The intrinsic connection between mathematics and art celebrated by Polycleitus has inspired various fields, leading to what is now a foundational principle in art education and practice.

The exploration of proportion in Polycleitus’s work has also stimulated dialog across other disciplines such as architecture and medicine, where understanding the human body remains pivotal. It’s fascinating to observe how the exploration of ratios and symmetry in a sculptor's studio has seeped into broader intellectual landscapes, influencing fields as diverse as scientific illustration and ergonomic design. In this way, Polycleitus's ideas serve as an enduring bridge across disciplines, reminding us of the interconnectedness of human knowledge.

The Philosophical Inquiry in Art

Polycleitus encouraged viewing sculpture not just as a representation of form but as an investigation into the essence of beauty itself. His sculptures invite viewers not merely to admire but to reflect upon the underlying ideals of symmetry and balance. This approach stimulates a philosophical inquiry: What is beauty? How does one render it? In Polycleitus’s time, these questions were not abstract considerations but integral to everyday life and understanding the world.

Today, as we navigate an increasingly complex visual culture, these questions maintain their significance. They challenge artists, designers, and thinkers to explore beyond the superficial, seeking answers that align with both timeless principles and evolving perceptions. Polycleitus’s legacy resides in this enduring inquiry, urging us to reflect on both the precision and spirituality of art.

Educational Role of Polycleitus in Modern Curriculum

In contemporary academia, where classical education forms the bedrock of art and design philosophies, Polycleitus remains a figure of study, emblematic of the synthesis between theory and practice. His principles are leveraged to teach budding artists the importance of understanding anatomy and proportion, thereby ensuring that their works are grounded in historical understanding while pushing new boundaries.

Courses in art history, fine arts, and even mathematics frequently reference Polycleitus’s Canon as a framework for understanding the evolution of aesthetic values over time. By studying his method, students gain insight not only into historical art but also into foundational principles that continue to shape perceptions of form and space in modern art and architecture. Hence, Polycleitus’s impact extends into educational realms, where he remains a touchstone for aspiring artists and scholars.

Cultural Significance and Global Footprint

Though Polycleitus's influence is most directly seen in Western art tradition, the essence of his canonical principles transcends geographical and cultural divides. Asian art, with its deep-seated appreciation for balance and harmony, resonates with the ethos found in Polycleitus's philosophy. These shared artistic values underscore a universal pursuit of beauty and proportion present across diverse cultures, facilitating cross-cultural dialogues in aesthetics and philosophy.

Furthermore, many contemporary artists globally find themselves circumnavigating back to classical ideals as they interrogate the transient nature of modern aesthetics. Whether through revisiting traditional forms or reinterpreting ancient philosophies using modern mediums, the global art community frequently nods to Polycleitus and his contemporaries as pioneering stewards of timeless beauty.

The Enduring Influence of Polycleitus

In closing, Polycleitus’s legacy is far more than a collection of fleeting bronze figures; it is an intellectual and artistic journey that continues to inform and inspire the evolving narrative of art history. His conceptualization of the human form as a fusion of physical and idealized beauty laid the foundational stones for countless artistic movements that would follow. From the classical busts of antiquity to the fluid abstractions in modern sculpting, the echoes of Polycleitus's teachings resonate powerfully.

As scholars continue to explore and reinterpret his work through various lenses, the genius of Polycleitus persists, illustrating the indelible connection between mathematical precision, philosophical exploration, and the undying quest for artistic excellence. The canon he shaped serves as both a historical monument and a living dialogue, ensuring that Polycleitus's spirit of inquiry and mastery remains ever-present in the artistic and intellectual tapestry of human culture.