Pulcheria : Une Impératrice Byzantine d'Exception

Introduction

Pulcheria, née en 399 et morte en 453, est l'une des figures les plus marquantes de l'Empire Byzantin. Fille de l'empereur Arcadius et de l'impératrice Eudoxie, elle a joué un rôle politique et religieux déterminant pendant une période cruciale de l'histoire byzantine. Bien souvent éclipsée par ses homologues masculins, Pulcheria a pourtant su imposer son autorité et son influence dans un monde dominé par les hommes. Cet article explore sa vie, ses réalisations et son héritage, mettant en lumière l'importance de cette impératrice méconnue.

Jeunesse et Ascension au Pouvoir

Pulcheria est née dans la pourpre, c'est-à-dire dans la famille impériale, un privilège rare à l'époque. Son père, Arcadius, était empereur d'Orient, tandis que sa mère, Eudoxie, était une femme ambitieuse et influente. Dès son plus jeune âge, Pulcheria a été éduquée dans les traditions chrétiennes et classiques, développant une piété profonde et une intelligence politique aiguisée.

À la mort de son père en 408, le trône revint à son frère cadet, Théodose II, alors âgé de seulement sept ans. Trop jeune pour régner seul, Théodose II fut placé sous la régence de plusieurs figures influentes, dont sa sœur aînée, Pulcheria. Bien qu'elle n'ait que neuf ans de plus que lui, Pulcheria prit rapidement les rênes du pouvoir, démontrant une maturité et une compétence rares pour son âge.

La Régence de Pulcheria

En 414, à l'âge de quinze ans, Pulcheria fut officiellement proclamée Augusta, un titre réservé aux impératrices byzantines. Elle assuma dès lors le rôle de régente pour son frère, Théodose II. Contrairement à d'autres femmes de son époque, Pulcheria n'était pas seulement une figure symbolique : elle joua un rôle actif dans la gouvernance de l'Empire.

L'une de ses premières décisions fut de renforcer la présence du christianisme dans la cour impériale. Elle fit vœu de chasteté et encouragea les membres de sa famille à en faire autant, consacrant ainsi leur vie à Dieu. Sous son influence, la cour devint un lieu de piété et de dévotion, reflétant ses convictions religieuses profondes.

Un Pouvoir à Double Tranchant

Malgré son autorité incontestable, Pulcheria dut faire face à de nombreuses oppositions. Les conseillers et les fonctionnaires de la cour, habitués à un pouvoir masculin, voyaient d'un mauvais œil l'influence croissante d'une jeune femme. Cependant, Pulcheria sut manœuvrer avec habileté, s'entourant de loyalistes et consolidant sa position.

Elle supervisa également l'éducation de Théodose II, lui inculquant les valeurs chrétiennes et les principes de gouvernance. Cependant, leur relation fut parfois tendue, notamment lorsque Théodose II épousa Eudocie, une femme dotée d'une forte personnalité. Les tensions entre Pulcheria et Eudocie finirent par éclater au grand jour, créant une division au sein de la cour.

Pulcheria et les Affaires Religieuses

L'une des contributions les plus durables de Pulcheria fut son engagement dans les affaires religieuses de l'Empire. À une époque où les controverses théologiques divisaient les chrétiens, elle prit des positions fermes pour défendre l'orthodoxie. Elle soutint notamment Cyrille d'Alexandrie lors du concile d'Éphèse en 431, qui condamna le nestorianisme et affirma la double nature, divine et humaine, du Christ.

Son influence religieuse ne se limita pas aux débats théologiques. Elle œuvra également pour la construction d'églises et la promotion du culte des saints, renforçant ainsi le christianisme comme pilier de l'Empire. Sa dévotion à la Vierge Marie fut particulièrement marquante, contribuant à l'essor du culte marial dans le monde byzantin.

Conclusion de la Première Partie

Pulcheria a marqué son époque par son intelligence politique, sa piété et sa capacité à gouverner dans un monde dominé par les hommes. Durant sa régence, elle a su maintenir la stabilité de l'Empire et influencer profondément la vie religieuse byzantine. Cependant, son histoire est loin d'être terminée. Dans la deuxième partie de cet article, nous explorerons les défis qu'elle a dû affronter, son exil temporaire et son retour triomphal au pouvoir.

Pulcheria : Exil et Retour Triomphal

Les Tensions avec Eudocie et la Chute Temporaire

L’arrivée d’Eudocie dans la vie de Théodose II marqua un tournant dans le règne de Pulcheria. Mariée à l’empereur en 421, Eudocie, une femme érudite et ambitieuse, ne tarda pas à contester l’autorité de Pulcheria. Le pouvoir, jusqu’alors exercé de manière incontestée par l’Augusta, se retrouva partagé, voire contesté. Les deux femmes incarnaient des visions différentes de la gouvernance et de la piété, ce qui engendra des conflits croissants au sein du palais.

En 431, quelques années après le Concile d’Éphèse, Pulcheria fut progressivement écartée des affaires impériales. Théodose II, influencé par ses conseillers et peut-être par Eudocie, décida de réduire son influence. Certaines sources historiques suggèrent même qu’elle fut contrainte de se retirer dans un palais éloigné de Constantinople, bien qu’elle conservât son titre d’Augusta. Cet éloignement politique fut un coup dur pour Pulcheria, qui avait consacré sa vie à servir l’Empire et la foi chrétienne.

Le Renouveau du Pouvoir

Cependant, l’exil de Pulcheria ne dura pas éternellement. Les années qui suivirent son éviction montrèrent les limites du pouvoir d’Eudocie et de Théodose II. L’impératrice Eudocie, impliquée dans des scandales et accusée d’adultère, tomba en disgrâce vers 443. Elle fut contrainte de quitter Constantinople pour Jérusalem, où elle passa le reste de sa vie dans une semi-retraite, consacrée à des œuvres religieuses.

Quant à Théodose II, son règne devint de plus en plus instable. Son gouvernement fut marqué par des crises administratives et militaires, notamment face aux menaces croissantes des Huns sous le commandement d’Attila. Affaibli et sans le soutien de sa sœur, l’empereur se retrouva isolé. En 450, Théodose II mourut des suites d’un accident de cheval, laissant l’Empire sans héritier direct. C’est alors que Pulcheria fit un retour remarqué sur la scène politique.

Le Mariage avec Marcien : Une Alliance Stratégique

Malgré son vœu de chasteté, Pulcheria accepta de se marier pour légitimer son pouvoir et assurer la stabilité de l’Empire. Son choix se porta sur Marcien, un général respecté et homme de confiance, qui avait déjà prouvé ses compétences militaires. Ce mariage, bien que purement symbolique sur le plan personnel, avait une portée politique considérable. En épousant Marcien, Pulcheria consolidait son autorité tout en s’assurant le soutien de l’armée.

Marcien fut proclamé empereur, mais il était clair que Pulcheria demeurait la véritable dirigeante. Contrairement à d’autres impératrices qui s’étaient effacées derrière leur époux, elle continua à jouer un rôle central dans les affaires de l’État. Sous leur règne conjoint, l’Empire connut une période de relative stabilité, malgré les pressions extérieures.

La Lutte contre les Huns et les Réformes Intérieures

L’une des premières décisions majeures du couple impérial fut de refuser de payer le tribut exigé par Attila. Contrairement à Théodose II, qui avait cédé aux exigences des Huns, Marcien et Pulcheria adoptèrent une position ferme. Cette décision audacieuse permit à l’Empire de regagner une partie de son prestige tout en limitant les saignées financières causées par les paiements aux envahisseurs.

Sur le plan intérieur, Pulcheria s’attela à réformer l’administration et à renforcer les institutions chrétiennes. Elle soutint activement l’Église, finançant la construction de nouvelles basiliques et favorisant la charité envers les pauvres. Son influence se fit également sentir dans le domaine législatif, où elle encouragea des mesures pour améliorer la condition des femmes et des plus démunis.

Le Concile de Chalcédoine et l’Affirmation de l’Orthodoxie

Le concile de Chalcédoine, en 451, fut l’un des événements religieux les plus importants de son règne. Convoqué pour résoudre les controverses autour de la nature du Christ, ce concile réaffirma avec force l’orthodoxie chrétienne contre les doctrines monophysites, qui niaient la double nature du Christ. Pulcheria y joua un rôle central, usant de son influence pour soutenir la position orthodoxe.

Ce concile eut des répercussions durables sur l’Église byzantine. En défendant la doctrine des deux natures du Christ, Pulcheria renforça l’unité religieuse de l’Empire, tout en marginalisant les courants jugés hérétiques. Bien que certaines provinces, comme l’Égypte et la Syrie, continuèrent à adhérer au monophysisme, l’autorité de Chalcédoine s’imposa comme un pilier de la théologie chrétienne.

La Mort et l’Héritage de Pulcheria

Pulcheria s’éteignit en 453, à l’âge de 54 ans, après une vie dédiée à l’Empire et à sa foi. Bien que sans enfant, elle laissa derrière elle un héritage politique et spirituel indéniable. Elle avait prouvé qu’une femme pouvait diriger avec fermeté et sagesse, brisant ainsi les conventions de son époque. Son règne mit en lumière l’importance des impératrices byzantines, qui continueraient à jouer un rôle crucial dans les siècles suivants.

Ses réalisations ne se limitèrent pas non plus au domaine politique. Son patronage des arts et de l’Église contribua à façonner la culture byzantine, alors en pleine expansion. Les monuments qu’elle fit construire, les textes qu’elle encouragea et les doctrines qu’elle défendit témoignent d’une femme dont l’influence dépassa largement son siècle.

À Suivre…

La vie de Pulcheria est un récit fascinant de pouvoir, de foi et de résilience. Dans la troisième et dernière partie de cet article, nous explorerons son impact posthume, la manière dont elle fut perçue par les historiens et son influence sur les générations suivantes d’impératrices byzantines. Son histoire, souvent éclipsée par celles des empereurs, mérite d’être redécouverte pour comprendre toute la complexité de l’Empire byzantin.

L'Héritage Immortel de Pulcheria

La Canonisation et la Mémoire Religieuse

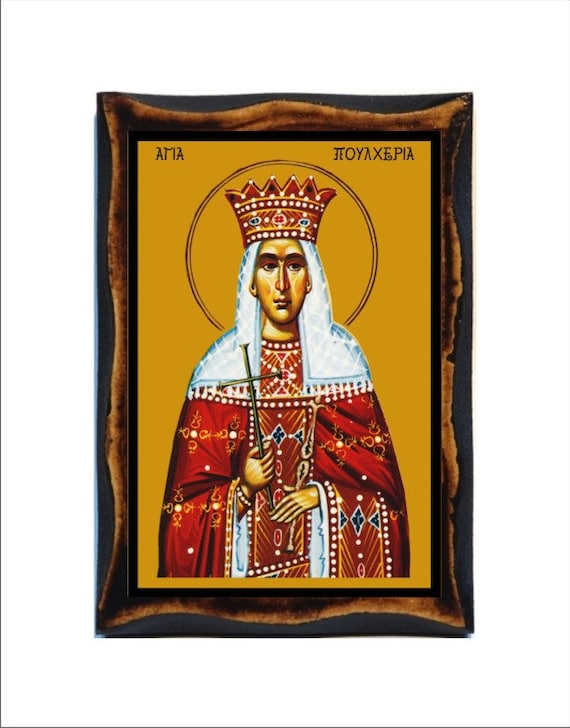

Après sa mort en 453, Pulcheria fut rapidement élevée au rang de sainte par l'Église orthodoxe. Cette canonisation précoce témoigne de l'impact profond de sa piété et de son action en faveur du christianisme. Contrairement à de nombreux souverains canonisés, Pulcheria ne dut pas sa sanctification à un martyre spectaculaire, mais à une vie entièrement consacrée au service de Dieu et de l'Empire. Les chroniqueurs byzantins, comme Sozomène et Théodoret de Cyr, la dépeignent comme un modèle de vertu chrétienne, soulignant particulièrement son vœu de chasteté maintenu malgré son mariage politique avec Marcien.

Son culte se développa particulièrement à Constantinople, où plusieurs églises lui furent dédiées. La plus célèbre, l'église Saint-Laurent, qu'elle avait fait construire et où elle fut inhumée, devint un important lieu de pèlerinage. Les mosaïques qui la représentaient aux côtés de la Vierge Marie (dont elle avait activement promu le culte) accentuaient son image de souveraine pieuse. Ce lien avec la théotokos était particulièrement significatif dans une société byzantine où la dévotion mariale prenait une importance croissante.

L'Influence sur les Impératrices Byzantines Postérieures

Pulcheria établit un modèle de gouvernance féminine qui inspira plusieurs générations d'impératrices byzantines. Théodora, l'épouse de Justinien (527-565), semble s'être largement inspirée de son exemple en associant pouvoir politique et engagement religieux. Comme Pulcheria, Théodora intervint activement dans les affaires théologiques, notamment lors de la crise du monophysisme, et utilisa son influence pour promouvoir ses protégés au sein de l'administration impériale.

La comparaison entre ces deux grandes figures mérite d'être approfondie. Si Théodora, ancienne actrice venue des couches populaires, diffère par ses origines de Pulcheria (née dans la pourpre impériale), toutes deux démontrèrent qu'une femme pouvait exercer un réel pouvoir dans l'ombre de son époux. Elles partageaient également cette capacité à faire coexister une piété affichée avec un sens aigu de la politique. L'historiographie byzantine ultérieure tendit d'ailleurs à idéaliser Pulcheria comme le "bon" contrepoint à l'image parfois controversée de Théodora.

L'Image de Pulcheria à Travers les Siècles

La perception de Pulcheria évolua significativement selon les époques. Au Moyen Âge byzantin, elle fut régulièrement citée comme exemplum dans les miroirs des princes, ces ouvrages destinés à l'éducation des souverains. Les auteurs y louaient sa sagesse politique et sa chasteté, présentées comme les deux piliers de son succès. Une anecdote souvent répétée soulignait comment elle avait fait inscrire sur sa porte les vers de Psaume 45:11 ("Écoute, ma fille, regarde et prête l'oreille") comme guide de conduite.

Les historiens modernes, en revanche, ont parfois émis des critiques sur certains aspects de son action. Son interventionnisme dans les affaires religieuses, notamment au concile de Chalcédoine, fut réinterprété par certains comme une ingérence du politique dans la théologie ayant contribué aux schismes ultérieurs. D'autres ont souligné l'aspect parfois autoritaire de son régime, notamment dans sa gestion des opposants. Néanmoins, la plupart s'accordent à reconnaître que son règne marqua un moment de stabilité dans un Empire en proie à de multiples crises.

Un Legs Architectural et Artistique

Pulcheria ne se contenta pas d'agir dans les sphères politiques et religieuses ; elle fut également une importante mécène. Outre l'église Saint-Laurent déjà mentionnée, elle supervisa la construction de l'église des Blachernes, qui devint l'un des principaux sanctuaires mariaux de Constantinople. Ce complexe religieux abritait notamment une relique insigne : le maphorion (voile) de la Vierge, rapporté de Terre Sainte en 473.

Les commandes artistiques qu'elle initia établirent des canons iconographiques durables. Les représentations des impératrices byzantines lui empruntèrent souvent ses attributs : le loros (écharpe impériale), la couronne à pendilia (perles suspendues), et le globe crucigère symbolisant la domination sur le monde chrétien. Ces éléments devinrent des standards dans les portraits impériaux durant tout le Moyen Âge byzantin.

Pulcheria dans l'Historiographie Contemporaine

Le renouveau des études byzantines au XXe siècle a permis de redécouvrir Pulcheria sous un nouveau jour. Les historiennes féministes, en particulier, ont souligné comment elle avait réussi à naviguer dans un système politique profondément patriarcal. Son habileté à instrumentaliser les attentes genrées de son époque - semblant respecter les conventions tout en les subvertissant - en fait un cas d'étude passionnant pour l'histoire des femmes au pouvoir.

Les travaux récents ont également mis en lumière son rôle dans la construction idéologique de l'Empire chrétien. Le concept de "dyarchie sacrée" qu'elle développa avec Marcien, où le pouvoir impérial se présentait comme le reflet terrestre de la royauté divine, influencera durablement la théorie politique byzantine. Cette vision se retrouvera plus tard dans la notion de symphonie des pouvoirs entre l'empereur et le patriarche.

Conclusion : Une Figure à Redécouvrir

L'histoire de Pulcheria dépasse largement le simple récit biographique. Elle incarne le paradoxe d'une femme qui dut jouer selon les règles d'un monde d'hommes pour finalement les transformer de l'intérieur. Son héritage se lit autant dans les institutions qu'elle contribua à façonner que dans les représentations mentales qu'elle modifia durablement.

Contrairement à de nombreuses femmes puissantes du passé souvent réduites à des caricatures (la séductrice, la cruelle, l'intrigante), Pulcheria parvint à imposer l'image complexe d'une souveraine pieuse mais politique, chaste mais pas naïve, pieuse mais pas bigote. Cette nuance explique peut-être pourquoi, malgré son importance historique, elle demeure moins connue que certaines de ses homologues masculins. À l'heure où l'on redécouvre les figures féminines oubliées de l'histoire, Pulcheria mérite assurément une place centrale dans le panthéon des grandes dirigeantes de l'Antiquité tardive.

Son histoire nous rappelle enfin combien l'Empire byzantin, souvent perçu comme une civilisation rigide, sut à plusieurs reprises intégrer des femmes au plus haut niveau du pouvoir - à condition qu'elles sachent, comme Pulcheria, maîtriser les codes complexes de ce jeu politique impitoyable. En cela, son parcours conserve une étonnante actualité pour quiconque s'intéresse aux dynamiques du pouvoir et du genre à travers les siècles.

The Legacy of Emperor Theodosius The Great

Theodosius I, known as Theodosius the Great, was a defining emperor of late Roman history. He was the last ruler to command a united Roman Empire. His reign fundamentally altered the religious and political landscape of the ancient world.

From his birth in Spain to his death in Milan, his life spanned a period of profound crisis and transformation. His policies solidified Nicene Christianity as the state religion and shaped the medieval world to come.

The Early Life and Rise of Theodosius I

Theodosius I was born on January 11, 347, in Hispania (modern Spain). He hailed from a prominent military family. His father, Count Theodosius, was a respected general who shaped his son’s early career.

This early military training proved invaluable for the future emperor. It prepared him for the immense challenges he would later face.

Military Apprenticeship Under His Father

The young Theodosius began his career alongside his father. He participated in the 368–369 campaign to Britain to suppress the "Great Conspiracy." This was a major coordinated invasion by Celtic and Germanic tribes.

He demonstrated significant skill and bravery during these campaigns. His success led to further promotions within the Roman military hierarchy.

Exile and Unexpected Ascension

Theodosius's rise was interrupted by political turmoil. Following his father’s execution in 376, he retired to his Spanish estates. This period of exile lasted until a dramatic turn of events in 379.

The Eastern Roman Emperor Gratian, facing a Gothic crisis, appointed Theodosius as co-emperor. He was given charge of the precarious Eastern provinces. This marked the beginning of his historic reign.

Military Campaigns and Imperial Consolidation

Upon his accession, Theodosius I inherited a dire military situation. The Balkans were ravaged by Gothic forces after the disastrous Roman defeat at Adrianople in 378. His initial focus was on securing the empire's frontiers.

He adopted a pragmatic strategy of negotiation and settlement with the Goths. This approach was controversial but necessary for immediate stability.

Victory Over Gothic and Sarmatian Threats

By 380, Theodosius had concluded a peace with the Goths. He celebrated a formal triumph in Constantinople on November 24 of that year. This success allowed him to redirect resources to other threats.

He also led campaigns against the Sarmatians and other invading groups. These victories helped to temporarily secure the Danube frontier. His reputation as a capable military commander grew significantly.

The War Against the Usurper Magnus Maximus

A major challenge to imperial unity arose in the West. The usurper Magnus Maximus seized power in Gaul and threatened Italy. Theodosius mobilized his forces to defend the legitimate emperor, Valentinian II.

The decisive clash occurred at the Battle of Poetovio in 388. Theodosius's army achieved a complete victory. Magnus Maximus was captured and executed on August 28, 388.

This victory restored Valentinian II to power in the West. It also demonstrated Theodosius's commitment to a unified imperial authority.

The Religious Revolution of Theodosius

The most profound impact of Theodosius the Great was in the realm of religion. His reign marked the final transition from pagan Rome to a Christian state. This transformation was both personal and political.

In 380, while gravely ill in Thessalonica, Theodosius was baptized by the Catholic Bishop Ascholios. This personal commitment to Nicene Christianity shaped all his subsequent policies.

Establishing Nicene Orthodoxy

One of his first major acts was to call the Council of Constantinople in 381. This council reaffirmed and codified the Nicene Creed. It officially condemned Arianism as a heresy.

The council's decisions provided a unified doctrinal foundation for the empire. Theodosius actively enforced these orthodoxy decrees across his domains. Heretical bishops were systematically expelled from their sees.

The Anti-Pagan Decrees and Laws

Between 391 and 392, Theodosius issued a series of sweeping edicts. These laws effectively outlawed pagan religious practice throughout the empire. They represented a definitive end to religious pluralism.

- The laws banned all public and private pagan sacrifices.

- They ordered the closing of pagan temples and sanctuaries.

- Pagan rituals like blood sacrifice or incense burning were classified as treason.

- Penalties for violation included death and confiscation of property.

These edicts of Theodosius I fundamentally transformed religious practice, making Nicene Christianity the official state religion of the Roman Empire.

The result was a revolutionary religious transformation. The Roman state was now explicitly a Christian theocracy. This model of church-state relations would dominate European history for centuries.

The Massacre of Thessalonica and Imperial Penance

A dark chapter in Theodosius I's reign unfolded in the city of Thessalonica in April of 390. A violent riot erupted, though historical accounts differ on the precise trigger. Some sources point to anger over the imprisonment of a popular charioteer, while others suggest resentment against a barbarian garrison stationed in the city.

In a fit of rage over the death of a senior military commander during the unrest, Theodosius ordered a brutal retaliation. His command resulted in a horrific massacre where at least 7,000 citizens were slaughtered in the city's coliseum. This act of extreme violence shocked the entire Roman world and stained his legacy.

Confrontation with Saint Ambrose

The spiritual and political repercussions were immediate and profound. Saint Ambrose, the powerful and respected Bishop of Milan, took an unprecedented step. He publicly condemned the emperor's action and refused Theodosius entry into the church, effectively excommunicating him.

Ambrose demanded that the emperor perform a public act of penance for his grave sin. This confrontation between secular power and ecclesiastical authority was a landmark event. It tested the boundaries of the emperor's power in the newly Christianized state.

A Historic Act of Submission

In a move that astonished contemporaries, Theodosius acquiesced to Ambrose's demand. The most powerful man in the Roman world humbled himself. He laid aside his imperial purple and performed eight months of public penance.

This act of submission by Theodosius the Great established a powerful precedent, demonstrating that even emperors were subject to the moral law of the Church.

The incident became one of the most memorable in early church history. It signaled a shift in the balance of power, establishing that spiritual authority could, at times, supersede imperial command.

The Climactic Battle of the Frigidus River

The pinnacle of Theodosius I's military career was the Battle of the Frigidus River in September 394. This conflict was the culmination of a renewed power struggle in the Western Roman Empire. After the death of Valentinian II, the Frankish general Arbogast elevated the scholar Eugenius as a puppet emperor.

Theodosius saw this as a direct challenge to his authority and the religious order he had established. Eugenius, backed by pagan senators, sought to restore traditional Roman religion. The battle was framed as a climactic clash between Christian and pagan factions for the soul of the empire.

A Two-Day Struggle for the Empire

The first day of battle was a disaster for Theodosius's forces. His Gothic allies bore the brunt of the fighting in a fierce frontal assault. Contemporary sources report that ten thousand Visigoths fell on that first day.

Despite these catastrophic losses, Theodosius refused to retreat. He spent the night in prayer, and on the second day, the fortunes of war shifted dramatically. A powerful windstorm, seen by Christian historians as a divine intervention, blew dust into the faces of Eugenius's troops.

Decisive Victory and Its Consequences

The "Bora" wind disrupted the enemy lines and allowed Theodosius's forces to breakthrough. Eugenius was captured and executed, and Arbogast took his own life shortly after. This victory eliminated the last significant pagan resistance to Christian rule.

- Consolidated Imperial Unity: Theodosius became the sole ruler of a unified Roman Empire for the final time.

- Crushed Pagan Revival: The defeat of Eugenius ended the hopes of a pagan restoration.

- Relied on Foederati: The high casualty rate among Gothic allies highlighted the empire's growing dependence on barbarian troops.

Many historians consider the Battle of the Frigidus to be Theodosius's greatest military achievement. It secured his religious revolution but also foreshadowed future conflicts with the empire's Germanic allies.

Theodosian Dynasty and Succession Plans

One of Theodosius I's most enduring legacies was the establishment of a lasting imperial dynasty. The Theodosian dynasty would rule the Roman Empire for over seventy years after his death. He carefully arranged marriages and appointments to ensure a smooth transition of power.

His children were central to these plans. From his first wife, Aelia Flaccilla, he had two sons, Arcadius and Honorius, and a daughter, Pulcheria. These children would become key instruments of his political strategy for securing the empire's future.

.Division of the Empire Between His Sons

As his health declined in 394, Theodosius made a momentous decision regarding the succession. He decreed that the empire would be divided between his two young sons. This partition would prove to be permanent, creating separate Eastern and Western Roman empires.

Arcadius, the elder son, was appointed Augustus of the East in 383 and was affirmed as ruler of the Eastern Roman Empire. Honorius, the younger son, was made Augustus of the West in 393 and would rule from Milan and later Ravenna. This division was intended to make governance more manageable but ultimately weakened the empire.

The Death of Theodosius the Great

Theodosius I died on January 17, 395, in Milan, after suffering from a debilitating edema. His death marked the end of an era and the beginning of a new, more fragmented phase in Roman history. He was succeeded by his sons, Arcadius in the East and Honorius in the West.

The death of Theodosius the Great marked the last time a single emperor would rule a unified Roman Empire, making his reign a pivotal turning point.

Despite his efforts to ensure stability, the Western Empire under Honorius would face increasing pressures. The settlement policies with Germanic tribes that Theodosius initiated would have profound long-term consequences.

The Long-Term Impact on the Roman Empire

The policies of Theodosius I had a deep and lasting impact that extended far beyond his lifetime. His religious settlement fundamentally reshaped European civilization. The establishment of Christianity as the state religion created a model for church-state relations that defined the medieval world.

Politically, his reign represented the last peak of unified Roman power. After his death, the Eastern and Western empires increasingly followed separate paths. The East, richer and more stable, evolved into the Byzantine Empire, which endured for another thousand years.

Consequences of the Gothic Settlements

Theodosius's pragmatic decision to settle Goths within the empire as foederati (allied troops) had mixed results. In the short term, it provided necessary military manpower and secured the Danube frontier. However, it also created powerful semi-autonomous Germanic groups within imperial borders.

These settled tribes, particularly the Visigoths, would later become a major threat to the Western Empire's stability. Some historians argue that this policy inadvertently contributed to the eventual collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century.

A Bridge Between Eras

Theodosius I stands as a monumental figure who bridged the classical and medieval worlds. He was the last emperor to rule a truly unified Roman state. At the same time, his policies set the stage for the Middle Ages.

- Religious Transformation: He completed the Christianization of the Roman state.

- Political Fragmentation: His division of the empire foreshadowed the end of imperial unity.

- Dynastic Stability: His family ruled for generations, providing continuity in a turbulent age.

His legacy is a complex tapestry of military triumph, religious zeal, and political pragmatism. He successfully navigated immense challenges but also set in motion forces that would ultimately transform the ancient world.

Administrative Reforms and Legal Legacy

The administrative policies of Theodosius I were as significant as his military and religious actions. He worked to streamline the vast imperial bureaucracy that governed the Roman world. His reforms aimed to strengthen central control and improve tax collection efficiency.

He issued numerous laws addressing corruption and administrative abuse. These edicts targeted provincial governors and other officials who exploited their positions. The goal was to create a more responsive and accountable government for his subjects.

The Theodosian Code and Legal Compilation

A monumental achievement initiated under Theodosius was the compilation of Roman law. In 429, he commissioned a committee to codify all imperial constitutions since the reign of Constantine I. This project aimed to create a unified legal system for the entire empire.

Although the Theodosian Code was not completed until 438, during his grandson's reign, its foundation was laid by Theodosius I. This code became the standard legal reference for late antiquity. It preserved Roman legal traditions and influenced later law codes, including the Justinian Code.

Economic Policies and Tax Burden

The constant military campaigns of Theodosius's reign required substantial financial resources. This led to increased taxation on the empire's landowning class and peasantry. The tax burden became a significant source of discontent in many provinces.

Despite these pressures, Theodosius attempted to balance fiscal needs with economic stability. He issued laws protecting taxpayers from excessive exploitation by collectors. However, the financial strain of maintaining large armies continued to challenge the empire's economy.

Cultural and Architectural Contributions

Theodosius I left a lasting mark on the physical landscape of the Roman Empire through ambitious building projects. His reign saw the construction and restoration of significant public works. These projects served both practical and symbolic purposes, reinforcing imperial authority.

In Constantinople, he enhanced the city's defenses and public spaces. The city continued to grow as the thriving capital of the Eastern Roman Empire. His architectural patronage demonstrated the empire's continued vitality despite political and military challenges.

The Theodosian Walls and Urban Fortifications

Although the famous Theodosian Walls of Constantinople were built after his death, their construction was part of his strategic vision. He initiated projects to strengthen key urban centers against external threats. These fortification projects reflected the increasing defensive posture of the late Roman state.

Major cities across the empire received improved walls and defensive structures. This investment in infrastructure helped protect urban centers from barbarian incursions. It represented a shift from offensive expansion to defensive consolidation.

Promotion of Christian Architecture

The religious transformation under Theodosius had a dramatic impact on architecture. The construction of Christian basilicas and churches accelerated throughout his reign. These buildings replaced pagan temples as centers of community life.

- Church Construction: Major churches were built in Constantinople, Milan, and other important cities.

- Adaptation of Basilicas: Roman basilica designs were adapted for Christian worship.

- Monastic Foundations: Support for monastic communities led to new religious architecture.

This architectural shift visibly demonstrated the triumph of Christianity. The landscape of the Roman world was physically transformed to reflect its new religious identity.

The Immediate Aftermath of His Death

The death of Theodosius I in 395 created a power vacuum that tested his succession arrangements. His sons Arcadius and Honorius were still young and inexperienced rulers. Real power often rested with their ministers and military commanders.

The division of the empire between East and West became more pronounced after his death. The two halves increasingly pursued separate foreign policies and faced different challenges. This fragmentation weakened the overall strength of the Roman world.

The Rise of Powerful Regents

In the Eastern Empire, the Praetorian Prefect Rufinus wielded significant influence over Arcadius. In the West, the general Stilicho claimed to have been appointed guardian of both young emperors by Theodosius. This contradiction led to immediate tension between the courts.

The competing claims of these powerful regents created political instability. This infighting hampered coordinated responses to external threats. The unity Theodosius had worked to maintain quickly began to unravel.

Renewed Gothic Threats

The Visigoths, under their new king Alaric, saw the transition of power as an opportunity. They rebelled against Roman authority and began raiding throughout the Balkans. The settlement policy that Theodosius had implemented now posed a serious threat.

The death of Theodosius the Great removed the only figure who could command the loyalty of both Roman and Gothic forces, leading to renewed conflict.

This rebellion demonstrated the fragility of Theodosius's diplomatic achievements. The Gothic problem he had managed through negotiation would escalate into a major crisis for his successors.

Historical Assessment and Modern Interpretations

Historians have offered varied assessments of Theodosius I's legacy throughout the centuries. Contemporary Christian writers praised him as a champion of orthodoxy and a model Christian ruler. Later historians have offered more nuanced evaluations of his complex reign.

Modern scholarship recognizes both his achievements and his failures. He successfully navigated immediate crises but some of his long-term policies had unintended consequences. His reign represents a pivotal moment of transition in world history.

Theodosius as a Transitional Figure

Most historians agree that Theodosius stands at the boundary between the ancient and medieval worlds. He was the last emperor to rule a unified Roman Empire in anything resembling its traditional form. After his death, the Western Empire entered its final century of existence.

His religious policies established the framework for medieval Christendom. The close relationship between church and state that he pioneered would characterize European civilization for over a millennium. In this sense, he helped create the medieval world.

Critical Perspectives on His Policies

Some modern critics argue that Theodosius's religious intolerance had negative consequences. The suppression of pagan traditions resulted in the loss of much classical learning and culture. His policies toward non-Christians created tensions that persisted for centuries.

- Religious Intolerance: His harsh measures against pagans and heretics established problematic precedents.

- Military Dependence: Reliance on barbarian forces weakened traditional Roman military institutions.

- Financial Strain: Constant warfare placed heavy burdens on the economy and taxpayers.

Despite these criticisms, most historians acknowledge that Theodosius faced enormously difficult circumstances. The challenges of his time would have tested any ruler.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of Theodosius the Great

The reign of Theodosius I represents one of the most significant turning points in Roman history. He successfully managed immediate military crises while implementing transformative religious policies. His decisions shaped the development of Europe for centuries to come.

As the last emperor of a unified Rome, he occupies a unique place in the historical narrative. His career bridges the classical world of antiquity and the emerging medieval civilization. The institutions he strengthened and the policies he implemented had lasting impacts.

Key achievements and Lasting Impacts

The most immediate legacy of Theodosius was the establishment of Nicene Christianity as the dominant religious force in Europe. This theological framework became the foundation of Western Christianity. His suppression of paganism and heresy created a religious uniformity that defined medieval Europe.

Politically, his division of the empire between his sons had profound consequences. While intended as an administrative measure, it accelerated the divergence between Eastern and Western Roman empires. The Eastern empire would continue as Byzantium for another thousand years.

Final Assessment

Theodosius the Great ruled during a period of extraordinary challenge and change. He confronted military threats, religious controversies, and administrative complexities with determination. While some of his solutions created new problems, he successfully guided the empire through turbulent times.

Theodosius I's reign marked the end of classical antiquity and the beginning of the medieval world, making him one of history's most consequential transitional figures.

His legacy is visible in the Christian culture of Europe, the legal traditions that influenced medieval law, and the political structures that evolved into medieval kingdoms. The world that emerged after his death bore the unmistakable imprint of his policies and decisions. Theodosius I truly earned his title "the Great" through his profound impact on the course of Western civilization.