Luigi Galvani: The Father of Modern Neurophysiology

Luigi Galvani, an Italian physician and physicist, revolutionized our understanding of nerve and muscle function. His pioneering work in the late 18th century established the foundation of electrophysiology. Galvani’s discovery of animal electricity transformed biological science and remains central to modern neuroscience.

Early Life and Scientific Context

Birth and Education

Born in 1737 in Bologna, Italy, Galvani studied medicine at the University of Bologna. He later became a professor of anatomy and physiology, blending rigorous experimentation with deep curiosity about life processes. His work unfolded during intense scientific debates about nerve function.

The Debate Over Nerve Function

In the 1700s, two theories dominated: neuroelectric theory (nerves use electricity) and irritability theory (intrinsic tissue force). Galvani entered this debate with unconventional methods, usingfrogs to explore bioelectricity. His approach combined serendipity with systematic testing.

The Revolutionary Frog Leg Experiments

Galvani’s most famous experiments began in the 1780s. While dissecting a frog, he noticed leg muscles twitching near an electrostatic machine. This observation led him to hypothesis: animal electricity existed inherently in living tissues.

Key Experimental Breakthroughs

- Frog legs contracted when metallic tools touched nerves near electric sparks.

- He replicated contractions using copper-iron arcs, proving bioelectric forces didn’t require external electricity.

- Connecting nerves or nerve-to-muscle between frogs produced contractions, confirming intrinsic electrical activity.

“Nerves act as insulated conductors, storing and releasing electricity much like a Leyden jar.”

Publication and Theoretical Breakthroughs

In 1791, Galvani published “De Viribus Electricitatis in Motu Musculari Commentarius” (Commentary on the Effects of Electricity on Muscular Motion). This work rejected outdated “animal spirits” theories and proposed nerves as conductive pathways.

Distinguishing Bioelectricity

Galvani carefully differentiated animal electricity from natural electric eels or artificial static electricity. He viewed muscles and nerves as biological capacitors, anticipating modern concepts of ionic gradients and action potentials.

Legacy of Insight

His hypothesis that nerves were insulated conductors preceded the discovery of myelin sheaths by over 60 years. Galvani’s work laid groundwork for later milestones:

- Matteucci measured muscle currents in the 1840s.

- du Bois-Reymond recorded nerve action potentials in the same decade.

- Hodgkin and Huxley earned the 1952 Nobel Prize for ionic mechanism research.

Today, tools measuring millivolts in resting potential (-70mV) directly trace their origins to Galvani’s frog-leg experiments.

The Galvani-Volta Controversy

The Bimetallic Arc Debate

Galvani’s work sparked a fierce scientific rivalry with Alessandro Volta, a contemporary Italian physicist. Volta argued that the frog leg contractions resulted from bimetallic arcs creating current, not intrinsic bioelectricity. He demonstrated that connecting copper and zinc produced similar effects using frog tissue as an electrolyte.

While Volta’s critique highlighted external current generation, Galvani countered with nerve-to-nerve experiments. By connecting nerves between frogs without metal, he proved contractions occurred independent of bimetallic arcs, validating his theory of inherent animal electricity.

- Volta’s experiments focused on external current from metal combinations.

- Galvani’s nerve-nerve tests showed bioelectricity originated within tissues.

- Both scientists contributed critical insights to early bioelectricity research.

Resolving the Debate

Their争论 ultimately advanced electrophysiology. Volta’s findings led to the invention of the Voltaic Pile in 1800, the first electric battery. Galvani’s work confirmed living tissues generated measurable electrical signals. Modern science recognizes both contributions: tissues produce bioelectricity, while external circuits can influence it.

“Galvani discovered the spark of life; Volta uncovered the spark of technology.”

Impact on 19th Century Neuroscience

Pioneers Building on Galvani

Galvani’s ideas ignited a wave of 19th-century discoveries. Researchers used his methods to explore nerve and muscle function with greater precision. Key milestones include:

- Bernard Matteucci (1840s) measured electrical currents in muscle tissue.

- Emil du Bois-Reymond (1840s) identified action potentials in nerves.

- Carl Ludwig developed early physiological recording tools.

Technological Advancements

These pioneers refined Galvani’s techniques using improved instrumentation. They measured millivolt-level signals and mapped electrical activity across tissues. Their work transformed neuroscience from philosophical debate to quantitative science, setting the stage for modern electrophysiology.

Modern Applications and Legacy

Educational Revival

Today, Galvani’s experiments live on in educational labs. Platforms like Backyard Brains recreate his frog-leg and Volta battery demonstrations to teach students about neuroscience fundamentals. These hands-on activities demystify bioelectricity for new generations.

Universities worldwide incorporate Galvani’s methods into introductory neuroscience courses. By replicating his 18th-century techniques, learners grasp concepts like action potentials and ionic conduction firsthand.

Neurotechnology Inspired by Galvani

Galvani’s vision of nerves as electrical conductors directly influences modern neurotechnology. Innovations such as:

- Neural prosthetics that interface with peripheral nerves.

- Brain-computer interfaces translating neural signals into commands.

- Bioelectronic medicine using tiny devices to modulate organ function.

These technologies echo Galvani’s insight that bioelectricity underpins nervous system communication. His work remains a cornerstone of efforts to treat neurological disorders through electrical stimulation.

Historical Recognition and Legacy

Posthumous Acknowledgment

Though Galvani died in 1798, his work gained widespread recognition in the centuries that followed. The 1998 bicentenary of his key experiments sparked renewed scholarly interest, with papers reaffirming his role as the founder of electrophysiology. Modern historians credit him with shifting neuroscience from vague theories to measurable electrical mechanisms.

Academic journals continues to cite Galvani’s 1791 treatise in milestone studies, including Hodgkin-Huxley models that explain ionic mechanisms underlying nerve impulses. His name remains synonymous with the discovery that bioelectricity drives neural communication.

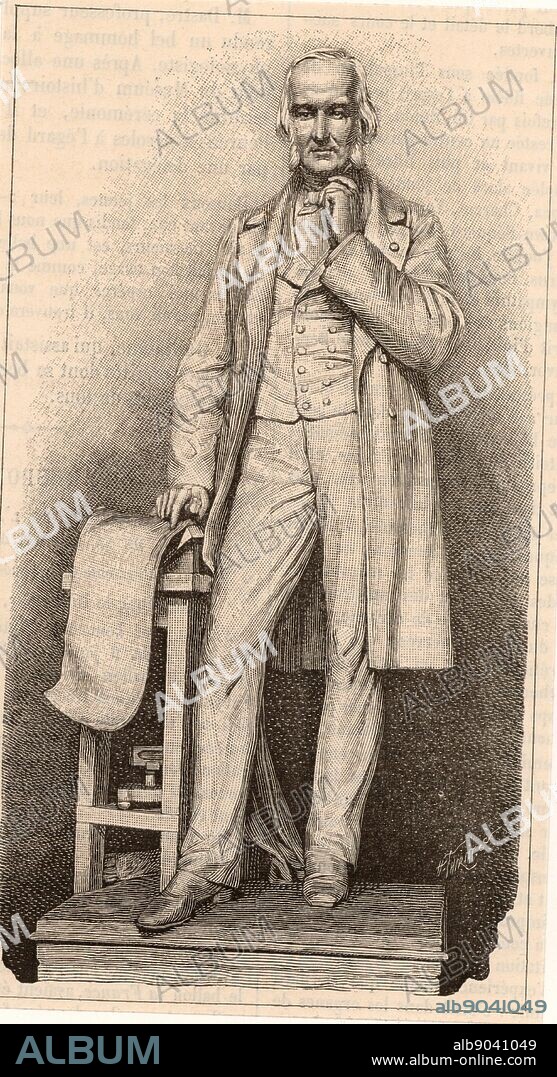

Monuments and Commemoration

Bologna, Italy, honors Galvani with statues, street names, and the Galvani Museum at the University of Bologna. The city also hosts an annual Galvani Lecture attended by leading neuroscientists. These tributes underscore his lasting impact on science and medicine.

- A bronze statue stands near Bologna’s anatomical theater.

- The Italian air force named a training ship “Luigi Galvani.”

- Numerous scientific awards bear his name.

Galvani’s Enduring Influence

Modern Recreations and Education

Galvani’s experiments remain classroom staples. Kits like Backyard Brains allow students to replicate his frog-leg and Volta battery demonstrations, bridging 18th-century discovery with 21st-century learning. These hands-on activities make abstract concepts like action potentials tangible.

Schools worldwide integrate Galvani’s work into curricula, emphasizing how serendipitous observation can lead to scientific breakthroughs. His story teaches the value of curiosity-driven research.

Advancements in Bioelectronics

Galvani’s vision of nerves as electrical conductors directly informs today’s neurotechnology. Innovations such as:

- Neural implants that restore sight or movement.

- Brain-computer interfaces for communication.

- Bioelectronic drugs that modulate organ function.

These technologies rely on the principle Galvani proved: living tissues generate and respond to electricity. His insights remain foundational to treating neurological disorders through electrical stimulation.

Quantitative Legacy

Galvani’s influence extends to precise measurement standards in neuroscience. Modern tools detect signals as small as millivolts, mapping resting potentials (-70mV) and action potentials (+30mV). These capabilities trace back to his frog-leg experiments, which first proved bioelectricity existed.

“Galvani gave us the language to speak to the nervous system—in volts and amperes.”

Conclusion

Summarizing Galvani’s Contributions

Luigi Galvani’s discovery of animal electricity reshaped our understanding of life itself. By proving nerves conduct electrical impulses, he laid the groundwork for:

- The field of electrophysiology.

- Modern neuroscience and neurotechnology.

- Quantitative approaches to studying the brain.

His work transcended 18th-century limitations, anticipating discoveries like myelin sheaths and ionic mechanisms by decades.

Final Key Takeaways

Galvani’s legacy endures in three critical areas:

- Scientific Foundation: He established nerves as biological conductors.

- Technological Inspiration: Modern devices mimic his principles.

- Educational Impact: His experiments teach generations about bioelectricity.

Luigi Galvani remains the father of modern neurophysiology not just for his discoveries, but for the enduring questions he inspired. Every time a neurologist monitors brain waves or an engineer designs a neural implant, they build on the spark Galvani first revealed. His work proves that sometimes, the smallest observation—a twitching frog leg—can illuminate the grandest truths about life.

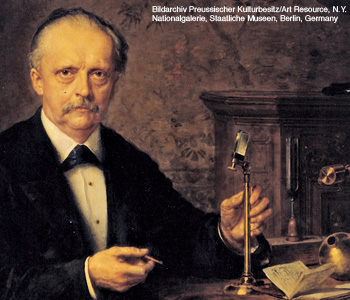

Hermann von Helmholtz: The Visionary Scientist Who Bridged Disciplines

The Early Years and Academic Foundations

Hermann von Helmholtz, born on August 31, 1821, in Potsdam, Prussia, was one of the most influential scientists of the 19th century. His work spanned multiple disciplines, including physics, physiology, psychology, and philosophy, making him a true polymath. The son of a gymnasium teacher, Helmholtz grew up in an intellectually stimulating environment, which nurtured his natural curiosity and passion for learning. Despite financial constraints, his father arranged for him to receive a strong education, setting the stage for his future achievements.

Helmholtz initially pursued a medical degree due to a state-funded scholarship that required military service afterward. He studied at the Royal Medico-Surgical Institute in Berlin, where he was deeply influenced by the teachings of physiologist Johannes Müller. Müller’s emphasis on the importance of physics and chemistry in understanding biological processes left a lasting impression on Helmholtz and shaped his interdisciplinary approach to science.

The Conservation of Energy: A Revolutionary Contribution

One of Helmholtz’s most groundbreaking contributions was his formulation of the principle of the conservation of energy. In 1847, at just 26 years old, he published On the Conservation of Force, a treatise that mathematically demonstrated that energy within a closed system remains constant—only transforming from one form to another. Though others had hinted at this concept, Helmholtz provided the rigorous mathematical foundation that solidified it as a fundamental principle of physics.

This work was met with skepticism at first, as many scientists still clung to the idea of vitalism—the belief that living organisms operated under different laws than inanimate matter. Helmholtz’s findings bridged the gap between biology and physics, proving that the same energy principles governed both living and non-living systems. His insights laid the groundwork for thermodynamics and influenced future giants of science, including James Clerk Maxwell and Max Planck.

Pioneering Work in Physiology

Beyond physics, Helmholtz made significant strides in physiology, particularly in the study of vision and hearing. His invention of the ophthalmoscope in 1851 revolutionized eye medicine by allowing doctors to examine the interior of the eye in detail. This device, still used today in modified forms, enabled the diagnosis of previously undetectable eye diseases and cemented Helmholtz’s reputation as a brilliant experimentalist.

Helmholtz also conducted extensive research on color vision and perception, building on the earlier work of Thomas Young. His trichromatic theory proposed that the human eye perceives color through three types of receptors sensitive to red, green, and blue light. This theory, later validated, remains central to our understanding of color vision and has applications in modern display technologies, such as televisions and computer screens.

The Nature of Perception and the Speed of Nerve Impulses

Another landmark achievement was Helmholtz’s experimental measurement of the speed of nerve impulses. Contrary to the prevailing belief that nerve signals were instantaneous, Helmholtz demonstrated that they traveled at a finite, measurable speed. Using frog muscles and precise electrical stimulation, he calculated the conduction velocity, proving that neural signals were not instantaneous but propagated at around 25 meters per second.

This discovery had profound implications for both physiology and psychology. It suggested that human perception was not immediate but rather involved measurable delays, raising questions about the nature of consciousness and reaction times. Helmholtz’s work in this area contributed to the emerging field of experimental psychology and influenced later thinkers like Wilhelm Wundt, often regarded as the father of psychology.

Acoustics and the Science of Sound

Helmholtz’s interests extended to the study of sound and hearing, where he made pioneering contributions. He developed the concept of resonance theory, which explained how the ear distinguishes different pitches. According to his theory, different parts of the inner ear’s cochlea resonate at specific frequencies, allowing the brain to interpret pitch. This idea, though refined over time, remains a cornerstone of auditory science.

He also invented the Helmholtz resonator, a device used to analyze sound frequencies. This simple yet effective tool allowed scientists to isolate and study specific tones, advancing both musical acoustics and the understanding of auditory perception. Helmholtz’s work in acoustics demonstrated his ability to merge theoretical insights with practical experimentation, a hallmark of his scientific method.

Academic Career and Legacy

Throughout his career, Helmholtz held prestigious academic positions, including professorships at the universities of Königsberg, Bonn, Heidelberg, and Berlin. He was a sought-after lecturer and mentor, inspiring generations of scientists. His ability to synthesize knowledge across disciplines made him a unifying figure in an era of increasing scientific specialization.

Helmholtz’s legacy endures not only in his specific discoveries but also in his approach to science. He championed the idea that scientific understanding required a combination of empirical observation, mathematical rigor, and theoretical innovation. His interdisciplinary mindset foreshadowed modern fields such as biophysics and cognitive science, demonstrating that the boundaries between disciplines are often artificial.

Hermann von Helmholtz passed away on September 8, 1894, but his ideas continue to resonate across multiple scientific domains. His life and work serve as a testament to the power of curiosity, persistence, and the relentless pursuit of knowledge.

To Be Continued…

Helmholtz and the Intersection of Science and Philosophy

Hermann von Helmholtz was not only a brilliant experimentalist but also a deep thinker who engaged with philosophical questions about the nature of reality and perception. His work bridged the gap between empirical science and epistemology, particularly in how humans acquire and process knowledge. Influenced by Immanuel Kant's philosophy, Helmholtz explored the idea that human perception is inherently shaped by the physiological structures of our senses and the mind.

In his 1867 work, Handbuch der physiologischen Optik (Handbook of Physiological Optics), Helmholtz argued that perception is an inferential process. He proposed that the brain constructs reality based on sensory inputs combined with learned assumptions—an idea that foreshadowed modern cognitive science. Unlike Kant, who believed in innate categories of thought, Helmholtz saw perception as an adaptive process refined through experience. This view aligned him with empiricism and influenced later psychologists and neuroscientists.

The Unconscious Inference Theory

A key concept in Helmholtz’s philosophical explorations was his theory of "unconscious inference." He suggested that much of human perception relies on subconscious deductions based on prior experiences. For example, when we see an object at a distance, our brain automatically infers its size, position, and depth—not through conscious calculation but through ingrained neural processes.

This idea was revolutionary, as it implied that perception was an active, interpretative process rather than a passive reception of sensory data. Helmholtz’s notion of unconscious inference laid the groundwork for later theories in cognitive psychology, including Hermann Lotze’s "local signs" theory and modern computational models of vision. His insights also challenged strict materialist views by suggesting that mental processes could not be reduced purely to physical laws without accounting for psychological adaptations.

Contributions to Electromagnetism and Fluid Dynamics

While Helmholtz is often celebrated for his work in physiology and energy conservation, his contributions to physics extended into electromagnetism and fluid dynamics. His investigations into vortices and their stability were foundational for both meteorology and astrophysics. In 1858, he introduced the concept of vortex motion, describing how swirling fluids (or gases) behave under different conditions.

This work had far-reaching implications: Lord Kelvin drew upon Helmholtz’s vortex theories to propose his atomic vortex model, and James Clerk Maxwell incorporated his ideas into electromagnetic field theory. Helmholtz’s mathematical treatment of vortices remains relevant in modern fluid mechanics, influencing studies of turbulence, weather systems, and even quantum fluids.

The Helmholtz Equation and Wave Theory

Another significant contribution was his formulation of the Helmholtz equation, a partial differential equation that describes wave propagation in various media. This equation became a cornerstone of acoustics, optics, and quantum mechanics. Physicists later used it to model everything from sound waves in concert halls to the behavior of electron orbitals in atoms.

Helmholtz’s wave theory also intersected with his physiological studies. He proposed that the ear’s ability to analyze complex sounds into individual frequencies—a principle now known as Fourier analysis in hearing—relied on resonant structures in the cochlea. This insight demonstrated his unique ability to connect abstract mathematical concepts with tangible biological phenomena.

Pioneering Meteorology and Environmental Science

Helmholtz’s fascination with fluid dynamics led him to investigate atmospheric phenomena, making him an early pioneer in meteorology. He studied the formation of weather patterns, including the dynamics of storms and cloud formations, and proposed theories about the Earth’s heat distribution. His work on thermal convection currents helped explain large-scale climatic processes, influencing later research into global atmospheric circulation.

Beyond theory, Helmholtz advocated for systematic, data-driven meteorological observations. His emphasis on precision measurement and interdisciplinary collaboration set standards for modern environmental science. Today, his ideas underpin climate modeling and weather prediction systems, underscoring his enduring impact on how we understand Earth’s complex systems.

Helmholtz’s Influence on Psychology and Neuroscience

Helmholtz’s research on perception and neural processes positioned him as a foundational figure in experimental psychology. His empirical approach to studying sensation and reaction times shifted psychology away from speculative philosophy toward rigorous laboratory science. Wilhelm Wundt, who established the first formal psychology laboratory in 1879, was one of Helmholtz’s students and built upon his mentor’s methods.

Modern neuroscience also owes much to Helmholtz. His work on nerve conduction velocity, sensory adaptation, and spatial perception anticipated later discoveries about neural plasticity and brain mapping. Researchers like Santiago Ramón y Cajal, who pioneered neuron theory, credited Helmholtz’s ideas as influential in shaping their understanding of neural organization.

The Mind-Body Problem and Scientific Materialism

Helmholtz’s views on the relationship between mind and body reflected the tensions of 19th-century scientific thought. While he upheld a materialist perspective—asserting that mental processes arise from physical brain activity—he rejected reductionist extremes. His emphasis on perception as an active, inferential process suggested that subjective experience could not be entirely explained by physiology alone.

This nuanced stance influenced later debates in philosophy of mind, particularly the discourse between dualism and physicalism. Helmholtz’s work provided a framework for exploring consciousness without abandoning scientific rigor, a balance that continues to resonate in contemporary cognitive science.

Recognition and Honors

Helmholtz’s brilliance earned him widespread acclaim during his lifetime. He was appointed to the Order Pour le Mérite, Prussia’s highest civilian honor, and received the Copley Medal from the Royal Society for his contributions to science. The Helmholtz Association of German Research Centers, one of Europe’s largest scientific organizations, bears his name as a testament to his enduring influence.

His interdisciplinary legacy is perhaps best encapsulated by the breadth of phenomena named after him: the Helmholtz coil (used in magnetic field experiments), Helmholtz free energy (in thermodynamics), and even the lunar crater Helmholtz. Each reflects his unparalleled ability to traverse scientific domains and uncover unifying principles.

Personal Life and Final Years

Behind the towering intellect was a man of quiet discipline and warmth. Helmholtz married Olga von Velten in 1849, and their partnership provided stability amid his demanding career. After her death, he remarried Anna von Mohl, who supported his work and hosted gatherings that brought together Europe’s leading intellectuals.

In his later years, Helmholtz suffered from declining health but remained intellectually active. He continued lecturing and writing until shortly before his death in 1894. His final works revisited themes of perception and epistemology, reflecting a lifetime of grappling with the mysteries of human understanding.

To Be Continued…

The Enduring Impact of Helmholtz’s Scientific Legacy

Hermann von Helmholtz’s influence extended far beyond the 19th century, shaping multiple scientific disciplines well into the modern era. His multidisciplinary approach—merging physics, biology, psychology, and mathematics—created frameworks that scientists still rely upon today. Unlike many of his contemporaries whose work became obsolete, Helmholtz’s theories often proved adaptable, evolving with new discoveries while retaining their foundational principles.

Helmholtz and the Foundations of Modern Neuroscience

One arena where Helmholtz’s impact is particularly pronounced is neuroscience. His experiments on nerve conduction velocity not only disproved the myth of instantaneous signaling but also demonstrated that the nervous system operates on measurable, electrochemical principles. This insight paved the way for future breakthroughs like Hodgkin and Huxley’s model of action potentials in the 1950s. Today, advanced imaging technologies like fMRI and EEG, which map brain activity in real time, owe an indirect debt to Helmholtz’s pioneering electrophysiology.

His ideas about perception also anticipated later discoveries about neural plasticity. Helmholtz’s "unconscious inference" theory suggested that the brain continuously refines its interpretations based on experience—a concept now confirmed by studies showing how neural pathways reorganize in response to learning or injury. Modern neurology often frames perception as a dynamic, predictive process, echoing Helmholtz’s views more than a century later.

The Helmholtz Legacy in Physics and Engineering

In physics, Helmholtz’s work on energy conservation and thermodynamics influenced the development of statistical mechanics and quantum theory. His mathematical rigor provided a template for later physicists like Ludwig Boltzmann and Max Planck, who expanded upon his thermodynamic models. Even the Helmholtz free energy equation (ΔA = ΔU – TΔS) remains a staple in physical chemistry, used to predict the spontaneity of reactions under constant temperature and volume.

Engineering applications of his research are equally pervasive. The Helmholtz resonator, originally designed for acoustic analysis, now appears in exhaust systems, musical instruments, and even architectural acoustics. Aerospace engineers apply his vortex theories to improve wing designs and turbulence management, while electrical engineers use Helmholtz coils—pairs of circular coils that generate uniform magnetic fields—in MRI machines and particle accelerators.

Helmholtz’s Unexpected Influence on Art and Music

Beyond hard science, Helmholtz’s studies on sound and vision had a surprising cultural impact. His 1863 book On the Sensations of Tone became essential reading for musicians and composers. By explaining how harmonics and overtones create timbre, Helmholtz provided a scientific basis for musical tuning systems. Innovators like Thomas Edison consulted his acoustical research when developing early sound recording devices.

Similarly, his color vision theory influenced the Impressionist and Neo-Impressionist movements. Artists like Georges Seurat applied Helmholtz’s principles of optical mixing—the idea that juxtaposed colors blend in the eye—to develop pointillism. Even modern display technologies, from RGB screens to digital printing, rely on his trichromatic model.

The Helmholtz Institutes: Carrying Forward a Vision

Perhaps the most visible testament to Helmholtz’s ongoing relevance is the Helmholtz Association, Germany’s largest scientific organization. Founded in 1948, its 18 research centers tackle complex challenges—climate change, neurodegenerative diseases, renewable energy—through the same interdisciplinary lens Helmholtz championed. The Association’s motto, “Understanding the Systems of Life and Technology,” mirrors his belief in unifying theoretical and applied science.

Notable initiatives include the Fritz Haber Institute (studying catalysis and sustainable chemistry) and the Alfred Wegener Institute (polar and marine research). These institutions embody Helmholtz’s ethos by fostering collaboration between physicists, biologists, and engineers, proving that his systemic approach remains vital in solving contemporary problems.

Debates and Reinterpretations: Helmholtz in Historical Context

While Helmholtz was widely revered, some of his ideas faced criticism or revision. His deterministic view of perception initially clashed with Gestalt psychologists, who emphasized innate organizational principles over learned inferences. Later, cognitive scientists bridged these perspectives, showing that perception involves both bottom-up sensory data (as Helmholtz argued) and top-down mental frameworks.

Similarly, his strict materialist stance drew fire from philosophers who accused him of neglecting subjective experience. Yet current neurophenomenology—which integrates neuroscience with first-person consciousness studies—reflects Helmholtz’s nuanced balance between empiricism and the complexities of human cognition.

Helmholtz vs. Contemporary Thinkers: A Comparative View

Helmholtz’s debates with contemporaries like Emil du Bois-Reymond (on the limits of scientific explanation) or Gustav Fechner (on psychophysics) reveal the intellectual ferment of his era. Unlike Fechner, who sought quantitative laws linking mind and matter, Helmholtz focused on mechanistic explanations of sensory processes. This tension between holistic and reductionist approaches persists in today’s brain research.

Helmholtz’s Pedagogical Influence: Shaping How Science is Taught

As an educator, Helmholtz transformed academic training by emphasizing laboratory experimentation alongside theory. His teaching methods at Berlin University inspired the modern research university model, where students engage in hands-on discovery. Pioneers like Albert A. Michelson (the first American Nobel laureate in physics) credited Helmholtz’s mentorship with shaping their experimental rigor.

His lectures for general audiences—collected in works like Popular Lectures on Scientific Subjects—were masterclasses in clear communication. By distilling complex ideas without oversimplifying, Helmholtz set a standard for public science education that influencers like Carl Sagan and Neil deGrasse Tyson would later emulate.

Final Days and Posthumous Recognition

In his last years, Helmholtz suffered from severe migraines and deteriorating vision—ironic for a man who revolutionized ophthalmology. Yet he continued writing, completing Epistemological Writings shortly before his death in 1894. His funeral in Berlin drew scientists, statesmen, and students, reflecting his stature as a national icon.

Today, Helmholtz’s name graces asteroids, lunar features, and countless scientific terms. But his true legacy lies in the ecosystems of interdisciplinary research he pioneered—from bioengineering labs merging medicine and robotics to AI researchers using his perceptual theories to train neural networks. In an age of hyperspecialization, his ability to synthesize knowledge across fields remains a guiding ideal.

Conclusion: The Polymath for the Ages

Hermann von Helmholtz was more than a summation of his discoveries; he represented a way of thinking about science itself. By refusing to compartmentalize nature into rigid disciplines, he revealed hidden connections—between sound and mathematics, energy and life, eye and mind. His career defied the modern dichotomy between “theoretical” and “applied” science, showing instead how each enriches the other.

As we face global challenges—from climate crises to AI ethics—Helmholtz’s example reminds us that solutions often lie at disciplinary intersections. Whether in a physicist studying neural networks or a musician exploring auditory neuroscience, his spirit endures wherever curiosity refuses boundaries. Two centuries after his birth, Helmholtz remains not just a historical figure, but a perpetual collaborator in humanity’s quest to understand its world.

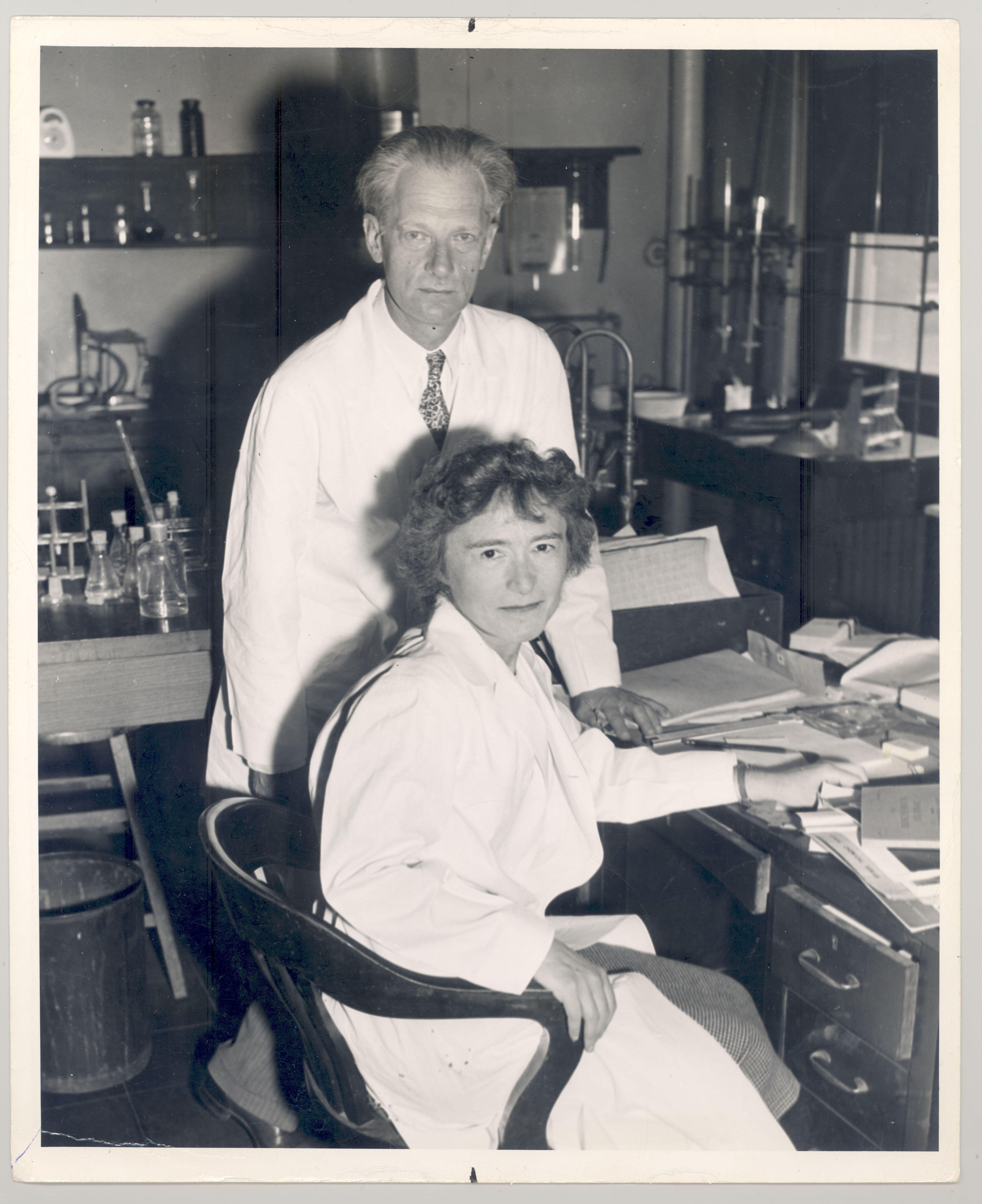

The Trailblazing Journey of Gerty Cori: Pioneering Woman in Science

In the annals of scientific history, few figures stand out as prominently as Gerty Cori, a trailblazer who overcame numerous barriers to reshape the landscape of biochemistry. Her incredible journey, marked by persistence and brilliance, demonstrates not only her scientific prowess but also her indomitable spirit in the face of adversity. As the first woman to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, Cori’s legacy extends far beyond her groundbreaking discoveries, inspiring generations of scientists to come.

Early Life and Education

Born in Prague in 1896 to a culturally-rich and intellectually-stimulating family environment, Gerty Theresa Radnitz Cori exhibited a passion for learning from a young age. Her parents, understanding the importance of education, ensured she received a well-rounded upbringing. Despite societal norms in early 20th-century Europe that often hindered women's access to higher education, Cori's determination propelled her along an unconventional path.

Gerty was deeply inspired by her uncle, a pediatrician, sparking her interest in medicine. In 1914, she defied the odds by enrolling in the German University of Prague's medical school where she was one of only a few female students. Here, she met her future husband and lifelong collaborator, Carl Ferdinand Cori. Both shared an enthusiasm for research that would later drive them to achieve remarkable feats in their careers.

Professional Challenges and Collaboration

After graduating in 1920, Gerty and Carl faced significant challenges in finding work. The aftermath of World War I severely limited opportunities in Europe, particularly for female scientists. Thus, in a bold move, the couple emigrated to the United States in 1922. Settling in Buffalo, New York, Gerty initially struggled to find positions befitting her qualifications. A stark reality during that era was that many institutions were unwilling to employ female scientists as faculty members, relegating Gerty to positions far below her expertise.

Regardless, her role as a research assistant did not deter her focus on scientific inquiry. She collaborated with Carl at the State Institute for the Study of Malignant Diseases, now known as the Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center. There, the duo began their pioneering research into carbohydrate metabolism. Working cohesively, they laid the groundwork for what would become known as the Cori cycle, elucidating the biochemical pathway responsible for converting glycogen to glucose, a process critical to understanding diabetes.

The Cori Cycle and Nobel Prize Recognition

Their relentless pursuit of knowledge culminated in a major scientific breakthrough. By 1929, the Coris had elucidated the Cori cycle, demonstrating how the body processes and regulates sugar – a discovery that held monumental implications for understanding metabolic diseases. Their work illustrated how muscle glycogen gets broken down to lactic acid and then is converted to glucose in the liver, offering vital insights into muscle physiology and biochemistry. Despite the challenging research environment of the time, their innovative methods and rigorous data analysis gained widespread recognition.

In 1947, Gerty and Carl Cori's contributions to medical science were honored with the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, shared with Argentine physiologist Bernardo Houssay. Gerty became not only the first woman to win a Nobel in that category but also among a small group of women scientists ever to receive the Nobel, a testament to her groundbreaking work and the collaborative synergy she maintained with her husband.

Legacy and Impact

Gerty Cori's story is not just one of scientific triumph but also an emblematic narrative of determination against prevailing gender biases. Her professional journey serves as an inspiring saga for many aspiring female scientists who face similar challenges today. She broke barriers, defied societal expectations, and in the process, made profound contributions to our understanding of human physiology.

Moreover, Gerty's work continues to influence modern research in metabolic diseases, diabetes treatment, and muscle development. Her legacy resonates within the scientific community, evidenced by the establishment of numerous awards and scholarships in her name, designed to empower women in science and foster the next generation of innovative thinkers.

In the continuation of this article, we will delve deeper into Gerty Cori's personal journey, exploring how her unique partnership with Carl Cori fostered their remarkable achievements, the societal hurdles they jointly overcame, and the lasting impact of their contributions to the world of biochemistry and medicine.

A Unique Scientific Partnership

The successful collaboration between Gerty and Carl Cori was a cornerstone of their scientific achievements. Their partnership was not only a bond of marriage but also a profound professional alliance, rooted in mutual respect and shared intellectual curiosity. This unique collaboration allowed them to push the boundaries of biochemistry and explore new horizons in metabolic research.

The Coris' dynamic began during their medical school days in Prague and continued to develop after they moved to the United States. Despite the fact that societal norms often relegated Gerty to a supporting role, the couple worked together as equals in the laboratory. Their shared passion for research and commitment to unraveling the mysteries of carbohydrate metabolism created an environment where their joint efforts thrived. Each brought a distinct set of skills and perspectives to their research endeavors, resulting in their many groundbreaking discoveries.

Their approach to scientific inquiry was characterized by rigorous experimentation and innovative thinking. Gerty, known for her meticulous attention to detail, complemented Carl's expansive vision, bolstering their research endeavors. The Coris’ teamwork and commitment to excellence not only enabled them to elucidate the intricacies of carbohydrate metabolism but also laid the groundwork for future research that would transform the understanding of various medical conditions.

Overcoming Societal Barriers

The challenges that Gerty Cori faced in her career were immense, mirroring the broader societal obstacles encountered by women in science during the early 20th century. Her journey was fraught with systemic hurdles, from limited professional opportunities to institutionalized gender bias. Despite these challenges, she remained steadfast in her pursuit of scientific excellence.

In an era when women's contributions to science were often overlooked or undervalued, Gerty's accomplishments paved the way for future generations. Her perseverance in the face of discrimination was a testament to her strength and resilience. Gerty's recognition as a Nobel laureate broke one of the highest glass ceilings in the scientific community, challenging perceptions and inspiring countless women to pursue careers in science and research.

Beyond her scientific achievements, Gerty Cori was a vocal advocate for gender equality in the scientific community. She used her platform to advocate for women’s rights and emphasize the need for greater inclusivity and diversity in research. Her efforts to address these systemic issues were groundbreaking, setting the stage for further advancements in women’s rights in science and academia.

Impact on Modern Science

The advancements in carbohydrate metabolism research made by Gerty and Carl Cori have had a lasting impact on modern science and medicine. Their work has significantly contributed to the understanding of metabolic processes and laid the foundation for contemporary studies into metabolic diseases, including diabetes and obesity.

Today, the principles of the Cori cycle are integral to the study of biochemical pathways and cellular metabolism. Researchers continue to build upon the Coris' insights, exploring the applications of their work in fields ranging from chronic disease management to athletic performance enhancement. The Cori cycle's role in lactic acid processing and gluconeogenesis remains a critical area of study in understanding muscle function and fatigue.

Furthermore, Gerty Cori’s research has opened new pathways for the development of therapeutic strategies to combat metabolic disorders. Her work's implications extend to the development of drug treatments and interventions that improve glucose regulation and energy balance, benefiting millions of individuals worldwide.

Pioneering a Path for Future Scientists

Gerty Cori's legacy is characterized by her groundbreaking research and her role as a pioneer for women in science. Her story is a testament to the power of perseverance, intellectual curiosity, and the pursuit of knowledge. By challenging societal norms and establishing herself as a leading figure in biochemistry, Gerty Cori has inspired countless scientists, both male and female, to pursue their passions unreservedly.

Her work continues to be celebrated in academia and scientific institutions worldwide. Numerous awards and fellowships have been named in her honor, each reflecting her enduring influence in the scientific community. These awards and programs seek to support and nurture the next generation of scientists, particularly women, emphasizing Gerty Cori's commitment to fostering diversity and equality in research.

In conclusion, Gerty Cori's life and work embody the spirit of scientific innovation and determination. Her legacy as a pioneering woman in science endures, encouraging future generations to push the boundaries of discovery and contribute to the advancement of knowledge in their chosen fields. As we continue this exploration of her remarkable life, we will delve further into the detailed scientific achievements of Gerty Cori, examining their specific contributions and the subsequent impact on the world of biochemistry and medical research.

Diving Deeper into Scientific Achievements

To fully appreciate Gerty Cori's impact on biochemistry, it is critical to examine the specifics of her scientific discoveries. Her pioneering work on the enzymatic transformation of glycogen was essential in understanding the complex biological processes that underpin metabolism. Building on the discovery of the Cori cycle, Gerty played an instrumental role in identifying and purifying the enzyme phosphorylase. This enzyme is crucial for glycogen breakdown, an area of research that was not only groundbreaking at the time but continues to be a cornerstone in biochemistry today.

In their research, the Coris demonstrated the importance of reversible biochemical reactions in cellular processes. Their work elucidated that phosphorylase regulates the conversion of glycogen to glucose-1-phosphate, an insight that further advanced the scientific understanding of how cells manage and utilize energy. These findings are now integral to educational curricula worldwide, illustrating essential biological processes that students encounter early in their scientific education.

Furthermore, Gerty and Carl's thorough exploration of glycogen metabolism provided a framework for future discoveries in enzyme research. Their methodologies and innovative approaches to experimental design have influenced numerous studies, cementing their work's relevance in both biochemistry and broader scientific disciplines.

Continuing Legacy and Recognition

Gerty Cori's legacy is enduring and multifaceted, encompassing her scientific contributions and her lifelong advocacy for gender equality in science. Her work has transcended her era, informing contemporary research and continuing to inspire new generations of scientists. Recognition of her contributions persists through various honors and memorials that ensure her place in scientific history is both acknowledged and celebrated.

Significantly, several institutions and academic endeavors commemorate her contributions to science. Gerty Cori's achievements are enshrined in the Cori Award, an honors program recognizing outstanding contributions in the field of biological chemistry. Furthermore, her name graces laboratories and research institutions, reflecting the profound respect she commands within the scientific community.

The impact of her legacy is also evident in educational programs that focus on empowering women in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). These initiatives, inspired by Gerty Cori's career, aim to dismantle barriers still present in scientific fields, advocating for equality and fostering a more inclusive environment within academia and research professions.

Gerty Cori's Influence on Future Scientific Exploration

Gerty Cori's work and the path she forged are more relevant today than ever. As we navigate an era of rapid scientific advancement and technological change, her example serves as a beacon of the potent combination of intellectual rigor and perseverance in the face of adversity. The determination she exhibited in her career underscores the value of tenacity and resilience, empowering modern researchers to challenge existing paradigms and pursue innovation with unwavering commitment.

Her story reflects the broader narrative of scientific progress—a continuous journey shaped by curiosity, collaboration, and the relentless pursuit of knowledge. The obstacles she overcame are representative of the ongoing struggle for equality in the scientific workforce, and her successes serve as powerful testament to what can be achieved when those barriers are dismantled.

Gerty Cori's life and research remain a source of inspiration, motivating scientists to tackle the pressing challenges of our time, from understanding complex biochemical systems to addressing global health issues. Her pioneering spirit exemplifies the best in scientific endeavor, driving future generations to explore uncharted territories with innovation and integrity.

In conclusion, Gerty Cori stands as a monumental figure in the history of science whose contributions continue to echo in the corridors of research and academia. Her indelible mark on biochemistry, coupled with her advocacy for women in science, ensures that her legacy will continue to influence the scientific world for decades to come. Through her work, Gerty Cori has not only expanded the boundaries of scientific knowledge but also paved the way for a more inclusive and equitable scientific community.

Lazzaro Spallanzani: Pioneering the Path to Modern Biological Sciences

In the pantheon of scientific history, the name Lazzaro Spallanzani often emerges as a beacon of pioneering inquiry and dedicated experimentation. Born on January 12, 1729, in Scandiano, Italy, Spallanzani grew up at a time when the fabric of science was undergoing a profound transformation. The 18th century heralded an era where the whispers of curiosity slowly began to evolve into the rigorous pursuit of knowledge and understanding. Within this dynamic epoch, Spallanzani positioned himself as a relentless seeker of truth, playing a pivotal role in shaping our modern understanding of biology and the life sciences.

Early Life and Education

Lazzaro Spallanzani's early exposure to education was both rigorous and spiritually rooted. His father, a lawyer, and his mother, from a noble family, placed great emphasis on academic excellence. Initially educated by Jesuits, Spallanzani found himself absorbing not just the theological dogmas of the time but also the intricacies of the natural world, fostering a lifelong quest for empirical reasoning.

His early schooling in Reggio Emilia led to a deeper involvement in the scholarly world. In 1749, he enrolled at the University of Bologna, where he pursued philosophy and logic, eventually leading to a fascination with mathematics and the natural sciences. This multidisciplinary foundation equipped Spallanzani with the analytical tools needed to embark on his groundbreaking scientific endeavors.

Contributions to Biology

Arguably, Spallanzani's most significant contributions to science were within the realm of biological research. His work was instrumental in challenging and ultimately debunking the theory of spontaneous generation—a widely held belief that life could arise from non-living matter without the need for ancestral lineage. Spallanzani's meticulous experiments in the field of microbiology laid the groundwork for future scientists like Louis Pasteur.

By the mid-18th century, many scientists accepted the idea that microscopic organisms could spontaneously generate. Spallanzani dared to question this notion, performing a series of experiments characterized by extraordinary precision for the time. By boiling nutrient-rich broths and sealing them away from the air, he demonstrated that microorganisms did not develop in the absence of existing life. These results pointed to the necessity of pre-existing germs, advocating for biogenesis—that life arises from existing life—a principle foundational to modern biology.

Discoveries in Reproduction and Physiology

Beyond microbiology, Spallanzani also made vital contributions to our understanding of animal reproduction and physiology. His investigations into reproduction were nothing short of revolutionary. He conducted extensive studies on the sexual reproduction of frogs, meticulously collecting and analyzing their reproductive behaviors. Incredibly, he successfully achieved one of the first instances of artificial insemination in animals, meticulously using frogs and even working with dogs to further validate his findings. This not only challenged existing preconceptions about reproduction but laid a critical foundation upon which modern reproductive biology could flourish.

Another area where Spallanzani's brilliance shone was his work in the field of animal physiology. His study on digestion and the gastric process was groundbreaking. By inserting small bags containing food into the stomach of animals, he meticulously examined the digestive process without external bias. He concluded that digestion was not merely a mechanical or fermentative process but one significantly influenced by gastric juices, which contain hydrochloric acid crucial for breaking down food substances.

Studying Respiration and Blood Circulation

Spallanzani extended his investigation to encompass the vital processes of respiration and blood circulation. Through a series of innovative experiments, he demystified the complex interrelation between respiration and the circulation of blood, highlighting the critical role of oxygen. His work predated yet paved the way for more detailed investigations into the mechanisms of respiration, allowing future scientists a deeper understanding of the biological necessities of life support functions.

Equipped with only the simplest of lab equipment by today's standards, Spallanzani showcased the power of observation, empirical inquiry, and rigorous testing—principles that remain integral to scientific inquiry. His experiments in these areas undeniably fortified the pillars upon which modern physiology rests.

Lazzaro Spallanzani's legacy is etched into the annals of scientific progress. His relentless curiosity, methodical experimentation, and willingness to question accepted norms set a new standard for scientific inquiry. Though much of his work became overshadowed by the towering figures of later centuries, Spallanzani’s spirit of inquiry and dedication to finding truth in nature's complexity remain enviable aspects of his character. As we pause to examine the rich tapestry of science's past, understanding Spallanzani’s contributions not only provides us insight into the historical progression of science but also inspires the next generation of scientists to pursue knowledge with the same vigor and dedication.

Innovations in Experimental Technique

Lazzaro Spallanzani’s genius was not limited merely to his discoveries. As a true innovator, he significantly advanced experimental techniques, which were crucial to his scientific breakthroughs. Emphasizing precision and repeatability, Spallanzani laid the groundwork for future scientists to refine their methodologies.

One of his most critical innovations was the use of sealed containers in experimental design, which provided a controlled environment to test his hypothesis on preventing contamination by microorganisms. By perfecting his apparatus and method, he addressed scientific curiosity with empiricism, enabling accurate observations that were less susceptible to external contamination. This attention to detail not only bolstered the credibility of his work but also inspired a newfound rigour in experimental science altogether.

Spallanzani was known for creative solutions when faced with methodological challenges. For instance, his use of frog eggs to demonstrate reproduction processes required that he innovate new handling techniques for small, delicate biological materials—an early precursor to the delicate nature of lab work required in modern genetics and reproductive science. By crafting specialized tools and introducing innovative experimental setups, he left a lasting impact on biological research methodologies.

The Influence of Travels and Correspondence

Widely traveled, Spallanzani's academic pursuits took him far beyond the borders of his native Italy. Travels throughout Europe offered him access to unparalleled intellectual exchange with his contemporaries and allowed him to widen his scientific perceptions considerably. His tenure at places such as the University of Padua and the University of Pavia further enabled him to collaborate with and learn from some of the period's most esteemed minds.

His correspondence with other eminent scholars of the Enlightenment, such as Charles Bonnet and Albrecht von Haller, illustrates his active engagement with the scientific community of his day. These exchanges of ideas were crucial not only for Spallanzani but for the advancement of science as a whole, as they facilitated the cross-pollination of research ideas across national and intellectual boundaries.

Spallanzani was not one to work in isolation. His exchanges weren't limited to purely scientific matters, but also extended to philosophical discussions which often colored the nature of scientific inquiry during the Enlightenment. Such scholarly dialogue was instrumental in fostering a broad-minded approach to science, showcasing the importance of interdisciplinary engagement, a factor today's scientists continue to find indispensable.

Challenges and Criticisms

Despite his numerous achievements, Spallanzani's work was not without its share of criticism and controversy. In a time where the scientific community was still clinging to archaic theories and beliefs, his efforts to refute the theory of spontaneous generation met with skepticism. For proponents of spontaneity, his findings challenged established ideations of life that extended richly into philosophical and religious realms. It wasn’t until later, with the advent of Pasteur’s research, that Spallanzani’s contributions were fully acknowledged for their revolutionary nature.

Moreover, his work extending into the realm of animal reproduction met with societal resistance given its potential impact on long-standing beliefs about life's sanctity and divine orchestration of life processes. Engaging with these domains stirred considerable debate but also spurred further inquiry and thought, which are indispensable for scientific progression.

Spallanzani's career also encountered challenges in the form of political turbulence. As a scientist working within a Europe swirling with political and social upheaval, his work often intersected with institutions skeptical or protective of maintaining the status quo. These aspects make his perseverance and commitment to pushing scientific boundaries even more commendable.

Legacy and Impact on Modern Science

Spallanzani's legacy is a rich tapestry woven with threads of innovation, rigorous methodology, and a fearless dedication to empirical science. The influence of his experimental methods is seen throughout modern scientific practices, particularly in the discipline of microbiology. His conceptual advances paved the way for seminal breakthroughs, including the germ theory of disease, which transformed medical sciences permanently.

While sometimes overshadowed by figures such as Louis Pasteur in the narrative of scientific history, his pioneering work into challenging the accepted norms undeniably set the stage for future discoveries. As Pasteur himself noted, Spallanzani’s experiments provided critical underpinning to his work, acknowledging the bedrock Spallanzani provided for microbiological studies.

In physiology, the understanding Spallanzani contributed regarding the digestion process remains foundational to gastroenterology, and his methods of artificial insemination have continuously evolved, leading to groundbreaking achievements in reproductive medicine. Today, techniques inspired by Spallanzani's initial works drive innovations in fertility treatments and genetic research.

The spirit of inquiry and dedication that Spallanzani encapsulated are reflective of the essential qualities needed in a scientist. He demonstrated that true innovation lies not simply in discovery but in the tools and methodologies we develop to challenge the world around us. In this way, Spallanzani’s contributions serve as not just historical achievements but as beacons guiding modern scientific enterprise towards greater understanding and progress.

Spallanzani's Exploration of Animal Behavior

Beyond his significant contributions to microbiology and physiology, Lazzaro Spallanzani ventured into the study of animal behavior, particularly echolocation and navigation in animals—a yet another testament to his relentless pursuit of understanding the natural world. His curiosity led him to investigate bats, intrigued by their remarkable ability to navigate in complete darkness.

Through painstaking observation and experimentation, Spallanzani demonstrated that bats were capable of navigating and avoiding obstacles even when their eyes were covered but became disoriented when their ears were obstructed. This early exploration into echolocation in bats laid the groundwork for further research into animal behavior and sensory biology. Although the precise understanding of echolocation would come later with the work of Donald Griffin, Spallanzani’s initial insights were foundational and opened new avenues of inquiry into how animals perceive and interact with their environment.

His studies emphasized the adaptability of life and challenged existing notions of sensory dependence, which were deeply rooted in human experience. By illustrating that animals could rely on senses beyond what humans found intuitive, Spallanzani contributed substantially to the realms of behavioral and evolutionary biology.

The Role of Religious Belief in His Work

During a time when science and religion often found themselves at odds, Spallanzani managed to navigate this complex landscape with commendable grace. As a priest, Spallanzani’s religious beliefs informed his philosophical outlook, intertwining with his passion for empirical science in a manner that allowed coexistence rather than contradiction. His work rarely incited conflict with religious authorities, who often viewed his research as exploring the divine complexity of life rather than contradicting it.

This harmonious balance is perhaps one reason why Spallanzani was so successful in his inquiries during an age when deviation from religious norms could provoke severe repercussions. He saw no contradiction in unveiling how nature operated while maintaining a belief in its divine design. Instead, his faith acted as a source of inspiration, fueling his desire to explore and understand the wonders of creation through the lens of observation and evidence.

Spallanzani's ability to harmonize his faith with his scientific pursuits showcases a model that encouraged dialogue rather than discord between scientific inquiry and religious belief—a dynamic that informed much of Enlightenment thought and can serve as a model for contemporary discussions about science and religion.

Recognition and Honors

Lazzaro Spallanzani's contributions did not go unnoticed during his lifetime, and he was widely respected by his peers for his pioneering insights and rigorous methodology. His reputation earned him numerous accolades and prestigious appointments, including his tenure as the chair of natural history at the University of Pavia, where he educated and inspired a generation of students who carried forward his passion for science and discovery.

His work earned recognition from numerous scientific societies across Europe, which highlighted the international impact of his studies. Moreover, instruments and methods he devised became widely adopted, marking his influence on practical scientific work and experimentation. His scientific rigour was admired universally, and his unyielding dedication to empirical evidence over speculation left a lasting impression on the scientific process.

Today, institutions and scientific endeavors continue to honor Spallanzani’s legacy, with various awards and species named in his memory—as a testament to his indelible influence on the biological sciences and his role in shaping the rigorous, methodical approach that underpins modern scientific inquiry.

Lazzaro Spallanzani’s Enduring Impact

Lazzaro Spallanzani passed away on February 12, 1799, but his legacy endures in countless facets of modern science. His embodiment of a holistic approach to understanding life—a synthesis of observation, experimentation, and open-mindedness—remains a bedrock methodology in scientific disciplines. Spallanzani’s work notably blurred boundaries that once segmented different sciences, promoting a unified approach that appreciated the intersectionality of biological processes.

In the laboratory, Spallanzani’s spirit transcends time, living through microscopes and petri dishes as researchers strive to emulate his meticulous nature. His contributions to biogenesis theory echo continuously in discussions surrounding the origin and evolution of life, reinforcing his relevance across centuries and disciplines. His influence extends across microbiology, physiology, ethology, and beyond, shaping the landscape of modern biological sciences.

Several of Spallanzani's principles form core tenets of scientific research today. His emphasis on controlled experiments, replication, and empirical evidence demonstrates how he was ahead of his time, encouraging scientists to employ a disciplined approach that corresponds with methodological naturalism—enabling discoveries that tangibly impact human health, understanding of the natural world, and even technological innovation.

It is in remembering and celebrating figures like Lazzaro Spallanzani that we find inspiration and guidance in our own journeys of scientific discovery. His life serves as a reminder of the power of curiosity, the importance of perseverance, and the impact one individual can have on expanding human knowledge. As we continue to delve deeper into the mysteries of the universe, we walk a path made clearer by the light of Spallanzani’s extraordinary contributions. Through his profound legacy, he remains a guardian of the adventurous spirit that propels science forward—encouraging inquiry, challenging norms, and unearthing the intricacies of the world in which we live.

Claude Bernard: Pioneer of Experimental Medicine

Claude Bernard, a name synonymous with the adventure of discovery in the realm of physiology,

was born on July 12, 1813, in the small village of Saint-Julien, France. Today, Bernard is

celebrated as one of the most significant figures in scientific history, not merely for his

groundbreaking contributions to medicine but also for his pioneering methods that

revolutionized the way scientific investigations are conducted. His insistence on observation,

experimentation, and logical thinking forms the bedrock of modern scientific research.

Early Life and Education

From a young age, Bernard showed an innate curiosity about the world around him.

Initially, he pursued an interest in literature, producing a comedy titled “La Rose du

Rhône.” However, the play's lackluster reception nudged him towards the medical field.

He later enrolled in the prestigious Collège de la Charité in Lyons, where he commenced

his formal training in medicine. Despite early financial struggles, Bernard's dedication

and resilience shone through, paving the way to the Paris Faculty of Medicine.

Revolutionizing Physiology

Claude Bernard's career as a physician and physiologist can hardly be overemphasized.

In the 19th century, medical science saw a transition from mere speculative theories to

experimental, evidence-based research thanks in large part to Bernard's methodology. He

fervently believed that conclusions about physiological processes must stem from empirical

observations and controlled experiments, as opposed to solely relying on philosophical debate.

One of Bernard’s most influential works involved studies on the functions of the pancreas

and liver. Before his time, the pancreas's role in digestion was largely misunderstood.

Through meticulous experimentation, he illuminated its function in secreting digestive enzymes,

a critical leap forward in understanding the digestive system. Equally remarkable was his

work on the liver, where he discovered glycogenesis—the process by which the liver

converts excess sugar into glycogen for storage, establishing an understanding of future

metabolic pathways.

The Milieu Intérieur

Perhaps Bernard’s most enduring legacy is the concept of the "milieu intérieur" or "internal

environment." He postulated that the stability of the internal environment is essential for

free and independent life. This revolutionary idea laid the foundation for the concept of

homeostasis—the body's ability to maintain a stable internal condition despite external changes,

a cornerstone of physiology and medicine today.

Bernard's insights into the mechanics of the internal environment led him to challenge

prevailing medical theories and practices. His persistent research on vascular dynamics

demonstrated the essential balance and complex interactions within the animal body.

Through these insightful conclusions, Bernard was able to transcend beyond his contemporaries,

charting a path that others would follow.

Bernard's experiments with curare, a plant-derived alkaloid used as a muscle relaxant,

further illustrated his experimental prowess. By elucidating its mechanism, he not only

deepened the understanding of neuromuscular function but also established methodologies

that laid groundwork for pharmacology.

His methodological rigor and emphasis on using the experimental method challenged the

status quo of medical interventions. Bernard proposed methods that required hypotheses

to be verified through experiments, emphasizing repeatability and objectivity. This

insistence on scientific rigor catalyzed advancements across numerous medical fields,

underscoring the universal applicability of Bernard’s principles beyond physiology.

Beyond Science

Beyond his role as a scientist, Bernard was a respected educator, holding a chair in

General Physiology at the Collège de France and later being appointed to the faculty at

the Museum of Natural History in Paris. His students benefitted immensely from his passion

for scientific inquiry and his tireless quest to illuminate the natural mechanisms underpinning

human health and disease. Bernard’s drive was fueled by a philosophical belief in the

unification of science and reason, maintaining that every scientific endeavor should be rooted

in skepticism until empirical proof is provided.