Ernst Ruska: The Visionary Scientist Behind Electron Microscopy

The Early Life and Education

Childhood and Initial Interests

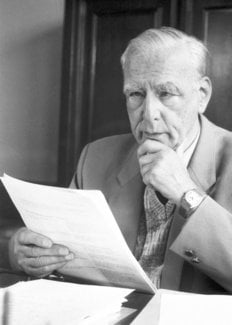

Ernst Ruska was born on May 10, 1906, in Königsberg, Germany (now Kaliningrad, Russia). From a young age, he displayed a keen interest in mathematics and electronics, which laid the foundation for his future scientific career. His father, Wilhelm Ruska, was a physics teacher at the Albertina University in Königsberg, and this early exposure to academia sparked Ruska’s curiosity and passion for science.

Navigating Through Higher Education

Ruska enrolled at the University of Göttingen in 1924, intending to study mathematics and physics. However, during his time there, he developed a strong interest in electrical engineering and electronics. This shift towards electronics coincided with the burgeoning field of electrical engineering around the world, a field that would later become central to his groundbreaking work.

The Path to Research

Towards the end of his studies, Ruska’s focus narrowed to theoretical electrical engineering, leading him to switch universities. In 1928, he transferred to the Technical University of Berlin, where he completed his doctoral thesis under the guidance of Heinrich Kayser, a renowned experimental physicist. Kayser encouraged Ruska’s budding interests in the application of electromagnetic waves and their interactions with matter, particularly in generating images of objects using these waves.

The Development of Electron Microscopy

The Birth of Electron Optics

During his doctoral work and post-graduate research, Ruska began developing the foundations of electron optics, a field that would lead to revolutionizing our ability to view the nanoscale realm. Building upon the principles of classical optics, he sought to exploit the unique properties of electrons and their interaction with materials. He realized that if one could manipulate electron beams with sufficient precision, it might be possible to achieve much higher magnifications than what was possible with traditional optical microscopes.

The First Electron Microscope

In the mid-1930s, Ruska started working at the German firm Telefunken, collaborating with Manfred von Ardenne. Their initial efforts focused on improving the resolution of electron microscopes. The first significant milestone was achieved when Ruska designed and built an electron lens capable of producing an image of a metal surface with unprecedented clarity. This was a critical breakthrough because previous attempts had failed due to technical limitations and design issues.

Publications and Recognition

In 1933, Ruska published his seminal paper in Poggendorff's Annalen der Physik, detailing his development of electron lenses and the construction of the first electron microscope. This publication was pivotal, as it showcased not only the potential of electron microscopy but also the ingenuity behind its development. Shortly after, he joined Ernst Abbe Professorship at the Institute for X-ray Physics at the University of Göttingen, further advancing his research.

Innovative Contributions and Scientific Legacy

The Zeiss Collaboration

Ruska's collaboration with the Carl Zeiss company proved to be crucial. Zeiss provided financial support and manufacturing capabilities, which were essential for scaling up Ruska's designs into practical instruments. Under their joint venture, Zeiss introduced the first commercial electron microscope in 1939, the EM 101A, which became a cornerstone in scientific research across various fields.

Continued Improvement and Expansion

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, Ruska continued to refine electron microscopy techniques. He tackled challenging problems like improving stability, enlarging the field of view, and enhancing resolution. These improvements were incremental yet transformative, paving the way for electron microscopy to become a ubiquitous tool in materials science, biology, and nanotechnology.

The Impact on Science and Industry

The development of electron microscopy by Ruska and his team had far-reaching implications. It not only allowed scientists to examine materials and biological samples with unparalleled detail but also opened new avenues for research in semiconductor technology, drug discovery, and understanding cellular structures. The ability to visualize molecules and atoms directly contributed to advancements in numerous industrial sectors, including electronics manufacturing and pharmaceuticals.

Award and Legacy

Nobel Prize and Honors

Despite his groundbreaking contributions, Ruska did not receive a Nobel Prize in his lifetime, although his work significantly influenced future Nobel laureates. His induction into the Panthéon des Découvertes (Hall of Fame of Discoveries) by the Académie des Sciences de Paris in 1990 was an acknowledgment of his lasting impact on scientific knowledge and technological advancement.

Enduring Legacy

As Ruska’s contributions to electron microscopy continue to be recognized and celebrated, his legacy serves as an inspiration for aspiring scientists and engineers. His relentless pursuit of scientific excellence and innovative thinking remains a testament to the power of curiosity and dedication in shaping the course of human progress.

Theoretical Foundations and Challenges

Theory vs. Practice

While Ruska’s practical innovations were immense, his theoretical insights were equally important. One of his key contributions was the introduction of a rigorous mathematical framework to describe the behavior of electron beams within microscopes. By applying principles from quantum mechanics and electromagnetism, he developed algorithms that explained how different elements could be isolated and distinguished within an image. This theoretical groundwork ensured that each advance in technology was grounded in solid physics, making electron microscopy both precise and reliable.

Hurdles and Overcoming Them

Despite his successes, Ruska encountered many challenges along the way. One major obstacle was the inherent nature of electrons themselves. Unlike visible light or X-rays, electrons have both wave-like and particle-like properties, known as wave-particle duality. This made them difficult to control and interpret. Ruska’s solution involved developing multi-zone lenses and more sophisticated deflection systems. These innovations allowed for greater control over the electron beam, enhancing the microscope's resolution beyond the limit set by classical optical theory.

The Role of Magnetism in Electron Microscopy

A critical component of Ruska’s electron lenses was based on magnetic fields. By bending electron beams with magnets, he could direct them towards specific areas of interest, much like using a lens in an optical microscope. However, the challenge lay in precisely controlling the magnetic fields to maintain constant curvature of the electron paths. Ruska worked meticulously to perfect these designs, often spending hours adjusting and recalibrating his equipment to achieve optimal performance.

The Evolution of Electron Microscopy Technology

Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

Another significant contribution by Ruska was the development of the Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM). Unlike the Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM), which passes electrons through a sample to generate an image, SEM scans a focused electron beam over the surface of a sample. This technique provided detailed surface information, which was particularly useful in studying electronic circuits and biological specimens.

The Role of Electron Energy Analysis

Beyond mere imaging, Ruska pushed the boundaries of electron microscopy by incorporating energy analysis capabilities. He introduced a device called an energy filter, which allowed scientists to analyze the energy distribution of electrons that passed through or interacted with a sample. This capability was instrumental in identifying various elements and compounds within microscopic samples, a feature that greatly enhanced the scientific utility of electron microscopy.

Adaptation and Application Across Disciplines

The applications of electron microscopy extended far beyond mere visualization. Researchers used Ruska’s techniques to study everything from the atomic structure of materials to the intricate details of cell membranes. In materials science, electron microscopy helped identify defects in semiconductors, paving the way for improved electronic devices. In biology, it offered unprecedented views of viral particles and bacteria, contributing significantly to medical research. These diverse applications underscored the versatility and importance of electron microscopy in modern science.

The Educational and Collaborative Impact

Educational Outreach

Ruska took an active role in training the next generation of scientists. He lectured at leading institutions and mentored countless students who went on to make their own mark in the field. His teaching emphasized hands-on experience and encouraged practical problem-solving, ensuring that the principles of electron microscopy were deeply ingrained in the minds of future researchers.

Collaborative Networks

Collaboration was also a hallmark of Ruska’s career. He worked closely with researchers from different disciplines and institutions, fostering a collaborative environment that spurred innovation. By inviting scientists to contribute to his projects and share their expertise, Ruska helped build a robust network of collaborators who continued to push the frontiers of scientific understanding.

The Establishment of Research Centers

To facilitate these collaborations and further his research goals, Ruska played a key role in the establishment of prominent research centers dedicated to electron microscopy. These centers served as hubs where scientists from various backgrounds could come together to advance the field. Through these centers, Ruska ensured that his work and the work of his colleagues would continue to have a profound impact on scientific research and technological development.

The Influence Beyond Science and Engineering

Technological Spin-offs

The technological innovations driven by Ruska’s research had profound effects far beyond the confines of academic laboratories. The principles behind electron microscopy led to the development of various other technologies, such as computerized tomography (CT), which has become essential in medical diagnostics. Further, the techniques developed for analyzing atomic structures inspired advancements in manufacturing processes and materials science, revolutionizing industries ranging from automotive to aerospace.

Public Awareness and Engagement

Beyond its scientific and practical impacts, Ruska’s work also raised public awareness about the capabilities of electron microscopy. Through exhibitions, articles, and public lectures, he explained the potential of these new tools to society at large. This engagement helped demystify cutting-edge science, inspiring public interest and support for ongoing research and technological development.

Long-Term Implications

The long-term implications of Ruska’s work extend well beyond his lifetime. Today, electron microscopy remains a fundamental tool in numerous scientific disciplines, driving innovations that continue to shape our understanding of the physical and biological worlds. From the development of new materials to the fight against diseases, the legacy of Ernst Ruska continues to influence and inspire future generations of scientists.

As we reflect on the extraordinary journey of Ernest Ruska, it is clear that his contributions go far beyond the confines of a single scientific discipline. His visionary approach, meticulous attention to detail, and unwavering commitment to pushing the boundaries of science have left an indelible mark on the landscape of modern technology and research.

The Last Years and Legacy

The Later Years and Recognition

Later in his career, Ruska faced some personal and professional challenges. Despite his significant contributions, he did not receive a Nobel Prize, a recognition that would have solidified his status as one of the greatest physicists of his time. Nonetheless, he continued to work and contribute to the field until the 1970s. Ruska retired from his professorship at the University of Regensburg in 1974 but remained deeply involved in ongoing research and development.

Continued Innovation and Mentoring

Even in retirement, Ruska remained passionate about mentoring younger scientists. He continued to advise and collaborate with researchers, ensuring that his expertise lived on long after his official retirement. His mentorship extended beyond technical guidance; he often shared philosophical insights and encouraged a broader perspective on the role of science in society.

Legacy Through Awards and Tributes

In 1968, Ruska was awarded the Otto Hahn Medal for his outstanding contributions to atomic physics. This recognition came late but was indicative of the growing appreciation for his work. In addition to the Otto Hahn Medal, Ruska was also honored by various institutions and societies. The Ernst Ruska Prize, established in 2000, is named in his honor and celebrates individuals who have made significant advancements in electron microscopy.

Influence on Modern Science and Society

Ruska’s work has had a lasting impact on modern science and society. The tools and techniques he developed continue to be foundational in a wide range of disciplines. Electron microscopy has become indispensable in fields such as materials science, biophysics, and nanotechnology, driving forward innovations that were unimaginable in Ruska’s era.

Conclusion

The Endless Frontier of Science

Ernst Ruska’s life and career exemplify the enduring power of scientific curiosity and innovation. His visionary ideas and tireless efforts paved the way for remarkable advances in microscopy and related technologies. Ruska’s legacy serves as a reminder of the possibilities that lie at the intersection of basic research and practical application.

Reflection on His Impact

As we look back on Ernst Ruska’s work, it becomes clear that his contributions have transcended the boundaries of microscopy. His approach to scientific inquiry, characterized by a deep commitment to understanding the fundamental principles underlying natural phenomena, continues to inspire researchers worldwide. Today, the tools and techniques that Ruska developed remain at the forefront of scientific exploration, driving us closer to a deeper understanding of the physical world.

Ultimately, Ernst Ruska’s legacy lies not just in his pioneering discoveries but in the spirit of inquiry and collaboration that he fostered. His work reminds us that every great discovery begins with a simple question—what if we could see the unseeable? Ruska’s enduring legacy stands as a testament to the transformative power of science.

Bio: Ernst Ruska (1906–1988) was a pioneering German physicist known for his fundamental contributions to the field of electron microscopy. His invention of the electron microscope revolutionized scientific research, enabling unprecedented detail in the visualization of nanoscale structures. Despite facing personal and professional challenges, Ruska remained steadfast in his pursuit of scientific truth and contributed tirelessly to the field until his passing.

Max Delbrück: Nobel-Winning Pioneer of Molecular Biology

Introduction to a Scientific Revolutionary

Max Delbrück was a visionary scientist whose groundbreaking work in bacteriophage research laid the foundation for modern molecular biology. Born in Germany in 1906, Delbrück transitioned from physics to biology, forever changing our understanding of genetic structure and viral replication. His contributions earned him the 1969 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, shared with Salvador Luria and Alfred Hershey.

Early Life and Academic Foundations

Delbrück was born on September 4, 1906, in Berlin, Germany, into an academic family. His father, Hans Delbrück, was a prominent historian, while his mother came from a family of scholars. This intellectual environment nurtured young Max's curiosity and love for science.

Education and Shift from Physics to Biology

Delbrück initially pursued theoretical physics, earning his PhD from the University of Göttingen in 1930. His early work included a stint as an assistant to Lise Meitner in Berlin, where he contributed to the prediction of Delbrück scattering, a phenomenon involving gamma ray interactions.

Inspired by Niels Bohr's ideas on complementarity, Delbrück began to question whether similar principles could apply to biology. This curiosity led him to shift his focus from physics to genetics, a move that would redefine scientific research.

Fleeing Nazi Germany and Building a New Life

The rise of the Nazi regime in Germany forced Delbrück to leave his homeland in 1937. He relocated to the United States, where he continued his research at Caltech and later at Vanderbilt University. In 1945, he became a U.S. citizen, solidifying his commitment to his new home.

Key Collaborations and the Phage Group

Delbrück's most influential work began with his collaboration with Salvador Luria and Alfred Hershey. Together, they formed the Phage Group, a collective of scientists dedicated to studying bacteriophages—viruses that infect bacteria. Their research transformed phage studies into an exact science, enabling precise genetic investigations.

One of their most notable achievements was the development of the one-step bacteriophage growth curve in 1939. This method allowed researchers to track the replication cycle of phages, revealing that a single phage could produce hundreds of thousands of progeny within an hour.

Groundbreaking Discoveries in Genetic Research

Delbrück's work with Luria and Hershey led to several pivotal discoveries that shaped modern genetics. Their research provided critical insights into viral replication and the nature of genetic mutations.

The Fluctuation Test and Spontaneous Mutations

In 1943, Delbrück and Luria conducted the Fluctuation Test, a groundbreaking experiment that demonstrated the random nature of bacterial mutations. Their findings disproved the prevailing idea that mutations were adaptive responses to environmental stress. Instead, they showed that mutations occur spontaneously, regardless of external conditions.

This discovery was pivotal in understanding genetic stability and laid the groundwork for future studies on mutation rates and their implications for evolution.

Viral Genetic Recombination

In 1946, Delbrück and Hershey made another significant breakthrough by discovering genetic recombination in viruses. Their work revealed that viruses could exchange genetic material, a process fundamental to genetic diversity and evolution. This finding further solidified the role of phages as model organisms in genetic research.

Legacy and Impact on Modern Science

Delbrück's contributions extended beyond his immediate discoveries. His interdisciplinary approach, combining physics and biology, inspired a new generation of scientists. The Phage Group he co-founded became a training ground for many leaders in molecular biology, influencing research for decades.

The Nobel Prize and Beyond

In 1969, Delbrück was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on viral replication and genetic structure. The prize recognized his role in transforming phage research into a precise scientific discipline, enabling advancements in genetics and molecular biology.

Even after receiving the Nobel Prize, Delbrück continued to push the boundaries of science. He challenged existing theories, such as the semi-conservative replication of DNA, and explored new areas like sensory transduction in Phycomyces, a type of fungus.

Conclusion of Part 1

Max Delbrück's journey from physics to biology exemplifies the power of interdisciplinary thinking. His work with bacteriophages not only advanced our understanding of genetics but also set the stage for modern molecular biology. In the next section, we will delve deeper into his later research, his influence on contemporary science, and the enduring legacy of his contributions.

Later Research and Challenging Established Theories

After receiving the Nobel Prize, Max Delbrück continued to push scientific boundaries through innovative experiments and theoretical challenges. His work remained focused on uncovering fundamental biological principles, often questioning prevailing assumptions.

Challenging DNA Replication Models

In 1954, Delbrück proposed a dispersive theory of DNA replication, challenging the dominant semi-conservative model. Though later disproven by Meselson and Stahl, his hypothesis stimulated critical debate and refined experimental approaches in molecular genetics.

Delbrück emphasized the importance of precise measurement standards, stating:

"The only way to understand life is to measure it as carefully as possible."This philosophy driven his entire career.

Studying Phycomyces Sensory Mechanisms

From the 1950s onward, Delbrück explored Phycomyces, a fungus capable of complex light and gravity responses. His research revealed how simple organisms translate environmental signals into measurable physical changes, bridging genetics and physiology.

- Demonstrated photoreceptor systems in fungal growth patterns

- Established quantitative methods for studying sensory transduction

- Influenced modern research on signal transduction pathways

The Max Delbrück Center: A Living Legacy

Following Delbrück's death in 1981, the Max Delbrück Center (MDC) was established in Berlin in 1992, embodying his vision of interdisciplinary molecular medicine. Today, it remains a global leader in genomics and systems biology.

Research Impact and Modern Applications

Delbrück's phage methodologies continue to underpin contemporary genetic technologies:

- CRISPR-Cas9 development builds on his quantitative phage genetics

- Modern viral vector engineering relies on principles he established

- Bacterial gene expression studies trace back to his fluctuation test designs

The MDC currently hosts over 1,500 researchers from more than 60 countries, continuing Delbrück's commitment to collaborative science.

Enduring Influence on Modern Genetics

Delbrück's approach to science—combining rigor, creativity, and simplicity—shapes current research paradigms. His emphasis on quantitative analysis remains central to modern genetic studies.

Philosophical Contributions

Delbrück advocated for studying biological systems at their simplest levels before tackling complexity. This "simplicity behind complexity" principle now guides systems biology and synthetic biology efforts worldwide.

His legacy endures through:

- Training generations of molecular biologists through the Phage Group

- Establishing foundational methods for mutant strain analysis

- Promoting international collaboration in life sciences

Legacy in Education and Mentorship

Max Delbrück’s influence extended far beyond his publications through his role as a mentor and educator. His leadership of the Phage Group created a model for collaborative, interdisciplinary training that shaped generations of scientists.

Training Future Scientists

Delbrück emphasized quantitative rigor and intellectual curiosity in his students. At Cold Spring Harbor, he fostered a community where physicists, biologists, and chemists worked together—a precursor to modern systems biology.

- Mentored Gordon Wolstenholme, who later directed the Salk Institute

- Inspired Walter Gilbert, a future Nobel laureate in chemistry

- Established a culture of critical debate that accelerated scientific progress

Current Applications of Delbrück's Work

Delbrück’s methods and discoveries remain embedded in today’s most advanced genetic technologies. His approach continues to inform cutting-edge research across multiple fields.

Impact on Modern Genetic Engineering

The principles Delbrück established through bacteriophage studies are foundational to tools transforming medicine and agriculture:

- CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing relies on phage-derived mechanisms

- Viral gene therapy vectors use designs first explored in his labs

- Bacterial mutagenesis studies follow protocols he refined

"Delbrück taught us to see genes not as abstract concepts, but as measurable molecular machines."

Advancing Genomics and Virology

Today’s genomic research owes a debt to Delbrück’s emphasis on precise measurement. Modern sequencing technologies and viral dating methods build directly on his frameworks.

Key ongoing applications include:

- Pandemic preparedness through phage-based virus tracking

- Cancer genomics using mutation rate analysis he pioneered

- Synthetic biology circuits inspired by his Phycomyces studies

Conclusion: The Enduring Impact of Max Delbrück

Max Delbrück transformed our understanding of life at the molecular level through visionary experiments, interdisciplinary collaboration, and unwavering intellectual rigor. His work remains a cornerstone of modern genetics.

Key Takeaways

The legacy of Delbrück endures through:

- Nobel-recognized discoveries in viral replication and mutation

- The Max Delbrück Center’s ongoing research in molecular medicine

- A scientific philosophy that values simplicity behind complexity

As biology grows increasingly complex, Delbrück’s insistence on quantitative clarity and collaborative inquiry continues to guide researchers worldwide. His life’s work proves that understanding life’s simplest mechanisms remains the surest path to unlocking its deepest mysteries.

Louis Pasteur: The Father of Modern Microbiology

Introduction

Louis Pasteur, a name synonymous with groundbreaking discoveries in microbiology, chemistry, and medicine, remains one of the most influential scientists in history. Born on December 27, 1822, in Dole, France, Pasteur’s work laid the foundation for modern germ theory, vaccination, and pasteurization. His relentless curiosity and dedication to scientific inquiry transformed medicine and saved countless lives. This article delves into Pasteur’s early life, education, and his revolutionary discoveries that changed the course of science forever.

Early Life and Education

Louis Pasteur was born into a modest family in eastern France. His father, Jean-Joseph Pasteur, was a tanner and a former soldier, while his mother, Jeanne-Étiennette Roqui, instilled in him a strong sense of discipline and perseverance. Despite limited financial means, Pasteur’s parents prioritized his education, sending him to primary school in Arbois and later to the Collège Royal in Besançon.

Young Pasteur initially showed a keen interest in art, even producing several pastel portraits that demonstrated his artistic talent. However, his passion for science soon took precedence. In 1839, he enrolled at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris, where he focused on chemistry and physics. His academic brilliance earned him a doctorate in sciences in 1847, with dissertations on crystallography that hinted at his future scientific prowess.

Discoveries in Crystallography and Molecular Asymmetry

Pasteur’s early scientific career centered on crystallography—the study of crystal structures. In 1848, he made a groundbreaking discovery while studying tartaric acid, a byproduct of wine fermentation. He observed that tartaric acid crystals exhibited asymmetric shapes, bending light in different directions. This phenomenon, known as optical activity, led Pasteur to propose that molecules could exist in mirror-image forms—a concept now fundamental to stereochemistry.

Through meticulous experimentation, Pasteur demonstrated that only living organisms, such as yeast, could produce optically active compounds. This finding challenged prevailing notions of spontaneous generation—the idea that life could arise from non-living matter—and set the stage for his later work on fermentation and germ theory.

Fermentation and the Germ Theory of Disease

Pasteur’s fascination with fermentation began when he was approached by local winemakers struggling with spoiled batches. At the time, fermentation was poorly understood, often attributed to chemical processes rather than living microorganisms. Pasteur’s microscopic investigations revealed that yeast cells were responsible for alcohol production, while bacteria caused spoilage.

This discovery revolutionized industrial fermentation and led to Pasteur’s development of pasteurization—a heat-treatment process that kills harmful bacteria in liquids like milk and wine. More importantly, Pasteur’s work laid the groundwork for germ theory, the idea that microorganisms cause infectious diseases. This concept countered the widely held miasma theory, which blamed diseases on “bad air.”

Silkworm Disease and Applied Microbiology

In the 1860s, Pasteur turned his attention to pébrine, a disease devastating France’s silk industry. After years of research, he identified a parasitic microorganism as the culprit and introduced methods to prevent its spread, saving the industry from collapse. This success further solidified his reputation as a scientist who could bridge the gap between theory and practical application.

The Rise of Vaccination: From Chicken Cholera to Rabies

Pasteur’s most famous contributions came in the field of immunization. While studying chicken cholera in 1879, he accidentally discovered that weakened strains of bacteria could induce immunity. This principle became the basis for modern vaccines.

His landmark achievement, however, was the development of the rabies vaccine in 1885. After years of research, Pasteur successfully vaccinated a young boy, Joseph Meister, who had been bitten by a rabid dog. The treatment’s success marked the first effective rabies vaccine and cemented Pasteur’s legacy as a pioneer in immunology.

The Pasteur Institute and Legacy

In 1887, Pasteur founded the Pasteur Institute in Paris, dedicated to research in microbiology, infectious diseases, and public health. The institute became a global leader in scientific innovation, producing Nobel laureates and life-saving treatments.

Louis Pasteur passed away on September 28, 1895, but his impact endures. His work not only advanced science but also demonstrated the power of rigorous experimentation and perseverance. From pasteurization to vaccines, Pasteur’s discoveries continue to shape medicine and industry, proving that one man’s curiosity can change the world.

Pasteur's Scientific Methodology and Influence on Medicine

The Experimental Rigor of Pasteur

Louis Pasteur was not just a scientist; he was a meticulous experimentalist whose methods set the standard for modern scientific inquiry. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Pasteur relied on careful observation, controlled experiments, and reproducible results. His approach was methodical—he would often repeat experiments dozens of times to confirm his findings before drawing conclusions. This rigorous methodology was pivotal in debunking the theory of spontaneous generation, a widely accepted belief at the time that life could arise from non-living matter. His famous swan-neck flask experiment, where he proved that sterilized broth remained free of microbial growth unless exposed to airborne contaminants, was a masterclass in experimental design.

From the Lab to the Real World: Practical Applications

Pasteur’s genius lay in his ability to translate theoretical discoveries into practical solutions. His work on fermentation, for instance, not only explained the science behind the process but also provided brewers and winemakers with techniques to improve product quality and shelf life. Similarly, pasteurization—initially developed to prevent wine spoilage—was soon applied to milk, drastically reducing the incidence of diseases like tuberculosis and typhoid fever transmitted through contaminated dairy products. Pasteur understood that science had to serve humanity, a philosophy that drove him to tackle real-world problems with scientific precision.

The Germ Theory Revolution

Before Pasteur, the medical community largely adhered to the miasma theory, which attributed diseases to "bad air" or environmental factors. Pasteur’s work on fermentation and silkworm diseases provided irrefutable evidence that microorganisms were responsible for both spoilage and illness. This insight laid the foundation for germ theory, which was later expanded by Robert Koch, who established Koch’s postulates linking specific microbes to specific diseases. Together, Pasteur and Koch revolutionized medicine, paving the way for antiseptic surgery, sterilization techniques, and modern epidemiology.

Confronting Skepticism and Opposition

The Battle Against Spontaneous Generation

Pasteur’s assertion that life does not arise spontaneously but rather from pre-existing life forms was met with fierce opposition, particularly from naturalists like Félix Pouchet, who defended the old theory. The ensuing public debates, often held before scientific academies, were intense. Pasteur’s meticulous experiments, however, left no room for doubt, and by the 1860s, spontaneous generation was widely discredited. This victory not only strengthened Pasteur’s reputation but also underscored the importance of empirical evidence over philosophical speculation in science.

Controversy Over Vaccination

Even as Pasteur’s vaccination breakthroughs garnered acclaim, they were not without controversy. The rabies vaccine, in particular, drew skepticism from some medical professionals who questioned its safety and efficacy. Critics argued that Pasteur had rushed human trials—Joseph Meister’s case, though successful, was highly experimental. Yet, the undeniable success of his vaccines gradually silenced detractors. The establishment of the Pasteur Institute in 1887 further validated his work, providing a hub for continued research and vaccine development.

The Human Side of Pasteur: Personal Struggles and Triumphs

Health Challenges and Resilient Spirit

Pasteur’s relentless work ethic came at a personal cost. In 1868, at the height of his career, he suffered a stroke that left him partially paralyzed. Despite this, he continued his research with undiminished fervor, adapting his methods to accommodate his physical limitations. His family, particularly his wife Marie Laurent, played a crucial role in supporting his work, often assisting him in the lab and managing correspondence. Pasteur’s resilience in the face of adversity remains a testament to his dedication to science.

Patriotism and the Franco-Prussian War

A fervent patriot, Pasteur was deeply affected by France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71). He returned his honorary doctorate from the University of Bonn as a protest against German aggression and dedicated himself to restoring France’s scientific prestige. This period also saw him advocate for scientific education as a means of national rejuvenation, influencing reforms in France’s academic institutions.

Expanding the Scope: Veterinary and Agricultural Advances

Combating Anthrax

In the 1870s, anthrax was decimating livestock across Europe. Pasteur, building on the work of Robert Koch, developed a vaccine by attenuating the anthrax bacillus. His public demonstration at Pouilly-le-Fort in 1881—where vaccinated sheep survived while unvaccinated ones perished—was a media sensation and a turning point in veterinary medicine. This success not only saved countless animals but also bolstered public confidence in vaccines.

Poultry Cholera and the Birth of Attenuated Vaccines

Pasteur’s accidental discovery of attenuation (weakening pathogens to create vaccines) occurred while studying chicken cholera. After leaving a culture of the bacteria unattended, he found that it lost its virulence but still conferred immunity. This serendipitous breakthrough became the basis for future vaccines, including those for rabies and, eventually, human diseases like polio and measles.

Legacy in Public Health

Sanitation and Hygiene Advocacy

Pasteur’s work underscored the importance of sanitation in preventing disease. His findings influenced public health policies, leading to improved hygiene practices in hospitals, food production, and water treatment. Cities adopted stricter sanitation standards, reducing outbreaks of cholera, dysentery, and other waterborne illnesses.

The Global Impact of Pasteurian Science

Beyond France, Pasteur’s principles spread rapidly. The Pasteur Institute became a model for similar institutions worldwide, from Saigon to São Paulo, fostering international collaboration in microbiology. His emphasis on the scientific method and applied research continues to inspire scientists today, proving that curiosity coupled with practical ingenuity can solve humanity’s greatest challenges.

The Final Years and Enduring Impact of Louis Pasteur

A Scientist Until the End

Even in his later years, Pasteur remained actively engaged in scientific pursuits despite declining health. During the 1890s, he focused on refining rabies treatment protocols and investigating other infectious diseases. His work patterns became legendary - laboratory sessions would often begin before dawn and extend late into the evening, with Pasteur frequently skipping meals when absorbed in research. This unparalleled dedication continued until a second stroke in 1894 left him largely bedridden. Yet even then, he dictated notes and guided research from his home near the Pasteur Institute, demonstrating the same intellectual rigor that defined his career.

National Hero and International Recognition

By the time of his death on September 28, 1895, Pasteur had achieved mythical status in France. The government granted him a state funeral - a rare honor for a civilian - with military honors at the Notre-Dame Cathedral. His remains were later transferred to an elaborate neo-Byzantine crypt beneath the Pasteur Institute, where they reside today as a place of scientific pilgrimage. Internationally, universities and learned societies across Europe and America had already showered him with honors, including the prestigious Copley Medal from Britain's Royal Society. This global acclaim reflected how his discoveries transcended national boundaries to benefit all humanity.

Unfinished Work and Future Directions

Pasteur's Unrealized Research Ambitions

Remarkably, Pasteur left several promising research avenues unexplored due to failing health. His notebooks reveal keen interest in applying microbiological principles to cancer research, anticipating modern immunotherapy approaches by nearly a century. He also speculated about microbial involvement in neurological conditions and envisioned vaccines against tuberculosis and pneumonia - diseases that would only yield to medical science decades later. The Pasteur Institute would eventually realize many of these ambitions, including developing the BCG tuberculosis vaccine in 1921.

The Emergence of Molecular Biology

Pasteur's foundational work in microbiology directly enabled the rise of molecular biology in the 20th century. His demonstration that specific microbes caused specific diseases provided the conceptual framework for understanding viruses and eventually DNA. Key figures like Jacques Monod, who won the 1965 Nobel Prize for work on genetic regulation, explicitly acknowledged their debt to Pasteurian principles. Today's advanced vaccine technologies using mRNA and viral vectors represent the ultimate evolution of Pasteur's original vaccine concepts.

Debates and Reevaluations

Ethical Questions in Pasteur's Methods

Modern historians have reexamined some aspects of Pasteur's career, particularly his often secretive research practices and aggressive self-promotion. Critics note he sometimes took credit for others' discoveries, including Jean-Joseph Henri Toussaint's work on anthrax vaccination. The famous rabies vaccine trial with Joseph Meister has also been scrutinized for bypassing standard ethical protocols - though contemporaries judged these actions differently in the context of medical desperation. These reevaluations don't diminish Pasteur's achievements but present a more nuanced portrait of scientific progress.

Addressing Historical Misconceptions

Several Pasteur myths require clarification. Contrary to popular belief, he didn't invent the microscope but was an exceptional microscopic observer. Nor did he discover germs outright - rather, he proved their pathogenic role through systematic experimentation. The famous quote "Chance favors the prepared mind" authentically reflects his philosophy, unlike many misattributions found online. Such distinctions matter because they accurately represent how scientific breakthroughs actually occur: through perseverance building on prior knowledge.

The Pasteur Institute's Continuing Legacy

130 Years of Cutting-Edge Research

Since its founding, the Pasteur Institute has remained at the forefront of biomedical research. Its scientists discovered HIV in 1983 and have earned ten Nobel Prizes to date. The institute's current work spans emerging infectious diseases, antimicrobial resistance, neuroscience, and global health initiatives. Its decentralized model has expanded internationally, with 32 Pasteur Institutes now operating worldwide in a unique research network that fulfills Louis Pasteur's vision of science without borders.

Modernizing Pasteurian Principles

While honoring its founder's legacy, the institute continually adapts to new challenges. Recent advances include: 1) developing rapid diagnostic tests for Ebola and COVID-19, 2) pioneering research on gut microbiota, and 3) creating novel vaccine platforms. The original emphasis on interdisciplinary collaboration remains central, as seen in projects combining epidemiology, genomics, and artificial intelligence to predict disease outbreaks - a 21st century realization of Pasteur's systems-thinking approach.

Pasteur in Popular Culture and Education

Representations in Media

Pasteur's dramatic life has inspired numerous films, books, and documentaries. The 1936 biopic "The Story of Louis Pasteur" won Paul Muni an Academy Award for his portrayal of the scientist. More recent representations include graphic novels and animated features aimed at young audiences. These cultural artifacts reflect changing perceptions of science - from Pasteur as solitary genius to collaborative team leader - while maintaining his core image as a benefactor of humanity.

Teaching the Pasteurian Method

Science curricula worldwide use Pasteur's experiments as teaching tools. His swan-neck flask demonstration appears in virtually every microbiology textbook, providing students with a model of elegant experimental design. Modern educators emphasize his systematic approach to problem-solving over simplistic "Eureka moment" narratives. Many universities have established Pasteur Scholars programs encouraging students to tackle real-world problems through applied research, keeping his practical philosophy alive in new generations.

Final Assessment: The Measure of a Giant

Quantifying Pasteur's Impact

Attempting to quantify Pasteur's influence reveals staggering numbers: 1) pasteurization prevents an estimated 25 million cases of foodborne illness annually, 2) rabies vaccination saves over 250,000 lives yearly in endemic regions, and 3) his principles underpin $400 billion in global vaccine markets. Yet these metrics can't capture his conceptual contributions - establishing microbiology as a discipline, demonstrating science's power to solve practical problems, and creating the template for modern research institutions.

The Enduring Relevance of Pasteur's Vision

In an era of climate change, pandemics, and antimicrobial resistance, Pasteur's integrated approach to science seems more vital than ever. His ability to connect basic research with real-world applications offers a model for addressing contemporary challenges. The COVID-19 pandemic particularly underscored this, as mRNA vaccine development built directly upon Pasteurian foundations. As science advances into synthetic biology and personalized medicine, the core principles Pasteur established - rigorous methodology, interdisciplinary collaboration, and science in service of society - continue lighting the way forward.

A Legacy Without Expiration

Unlike the perishable liquids Pasteur sought to preserve, his intellectual legacy remains perpetually fresh. Each medical breakthrough - from antivirals to CRISPR-based therapies - extends the chain of knowledge he helped forge. The true measure of Pasteur's genius lies not in any single discovery, but in having created an entire framework for scientific progress that keeps yielding dividends 200 years after his birth. As microbiologist Rene Dubos observed: "Pasteur was not a man of his time, but a man of all times." This timeless relevance confirms his place alongside Galileo, Newton, and Einstein in the pantheon of scientists who fundamentally transformed humanity's relationship with the natural world.

Jacques Monod: A Pioneer of Molecular Biology

Early Life and Education

Jacques Lucien Monod was born on February 9, 1910, in Paris, France. From an early age, Monod exhibited a keen interest in the natural sciences, a passion that was nurtured by his father, Lucien Monod, a painter and intellectual. Monod's upbringing in an intellectually stimulating environment laid the foundation for his future contributions to science. He attended the Lycée Carnot in Paris, where he excelled in his studies, particularly in biology and chemistry. His fascination with life sciences led him to pursue higher education at the University of Paris, where he earned his bachelor's degree in 1931.

Monod's academic journey took a significant turn when he joined the laboratory of André Lwoff at the Pasteur Institute. Under Lwoff's mentorship, Monod developed a deep understanding of microbial physiology and genetics. This period was crucial in shaping his scientific outlook, as he began to explore the mechanisms of enzyme adaptation in bacteria. His early research laid the groundwork for what would later become his most celebrated contributions to molecular biology.

Scientific Contributions and the Operon Model

One of Jacques Monod's most groundbreaking achievements was his work on the regulation of gene expression, which he conducted in collaboration with François Jacob. Together, they proposed the operon model, a revolutionary concept that explained how genes are controlled in bacteria. The operon model describes a cluster of genes that are transcribed together and regulated by a single promoter. This discovery provided profound insights into how cells switch genes on and off in response to environmental changes.

The lac operon, a specific example studied by Monod and Jacob, became a cornerstone of molecular biology. It demonstrated how the presence or absence of lactose in the environment could trigger or inhibit the production of enzymes needed to metabolize it. This elegantly simple yet powerful model earned Monod and Jacob the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1965, shared with André Lwoff, for their discoveries concerning genetic control of enzyme and virus synthesis.

Philosophical and Ethical Perspectives

Beyond his scientific achievements, Jacques Monod was a thinker who engaged deeply with philosophical and ethical questions. In his book "Chance and Necessity" (1970), Monod explored the implications of molecular biology for understanding life's origins and evolution. He argued that life arose from random molecular interactions, governed by the laws of chemistry and physics, and that evolution was driven by chance mutations and natural selection. This perspective challenged traditional notions of teleology, the idea that life has an inherent purpose or direction.

Monod's philosophical stance often placed him at odds with religious and ideological doctrines that emphasized predetermined design in nature. His views sparked debates not only in scientific circles but also among theologians and philosophers. Despite the controversy, Monod remained steadfast in his belief that science, grounded in empirical evidence, was the most reliable path to understanding the universe and humanity's place within it.

Legacy and Influence

Jacques Monod's legacy extends far beyond his scientific discoveries. He played a pivotal role in establishing molecular biology as a distinct discipline, bridging the gaps between biochemistry, genetics, and microbiology. His work laid the foundation for countless advancements in genetic engineering, biotechnology, and medicine. Today, the principles he elucidated continue to guide research in gene regulation and cellular function.

Monod's influence also permeated the scientific community through his leadership roles. He served as the director of the Pasteur Institute from 1971 to 1976, where he fostered a collaborative and innovative research environment. His dedication to scientific rigor and intellectual freedom inspired generations of researchers to pursue bold and transformative ideas.

In recognition of his contributions, Monod received numerous accolades, including the Nobel Prize, membership in prestigious academies, and honorary degrees from universities worldwide. His name lives on in the names of institutions, awards, and even a crater on the moon, honoring his indelible mark on science and human knowledge.

The War Years and Resistance Efforts

Jacques Monod's life took a dramatic turn during World War II, when he became an active member of the French Resistance. Despite the risks, Monod joined the underground movement, using his scientific expertise to aid the Allied cause. He worked closely with the resistance network "Combat," forging documents, smuggling intelligence, and even assisting in sabotage operations against Nazi forces. His bravery and strategic thinking made him a key figure in the resistance, though he rarely spoke about his wartime experiences later in life.

During this turbulent period, Monod also continued his scientific research under difficult conditions. The Pasteur Institute, where he worked, became a hub for clandestine activities, with scientists discreetly conducting experiments while secretly aiding the resistance. Monod's dual role as a researcher and a resistance fighter exemplified his unwavering commitment to both science and liberty. His experiences during the war profoundly influenced his later perspectives on ethics, freedom, and the responsibilities of scientists in society.

Post-War Research and the Birth of Molecular Biology

After the war, Monod returned to full-time research, focusing on the study of bacterial enzymes and their regulation. His work in the late 1940s and 1950s sought to understand how microorganisms adapted to changes in their environment. A pivotal breakthrough came when Monod, alongside collaborators like François Jacob and André Lwoff, developed the concept of "enzyme adaptation." This research eventually led to the formulation of the operon theory, which explained how genes could be turned on or off in response to environmental cues.

The discovery of messenger RNA (mRNA) was another landmark moment in Monod’s career. By demonstrating that RNA acted as an intermediary between DNA and protein synthesis, Monod and Jacob provided a crucial piece of the puzzle in understanding how genetic information is expressed. Their experiments with E. coli bacteria revealed that gene expression was not static but tightly controlled, laying the groundwork for the modern understanding of gene regulation.

Collaboration with François Jacob and the Nobel Prize

The partnership between Jacques Monod and François Jacob was one of the most prolific in the history of molecular biology. Their complementary skills—Monod’s biochemical precision and Jacob’s genetic insights—allowed them to tackle complex biological questions with remarkable clarity. One of their most famous collaborations involved studying the lactose metabolism in E. coli, which led to the discovery of the lac operon. This system demonstrated how bacteria could economize resources by producing enzymes only when needed, a principle later found to be universal in living organisms.

In 1965, Monod, Jacob, and Lwoff were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discoveries concerning genetic regulation and viral replication. The Nobel committee acknowledged that their work had fundamentally changed the way scientists understood cellular function. For Monod, the prize was not just a personal triumph but a validation of molecular biology as a transformative scientific discipline.

Monod’s Leadership in Science and Policy

Beyond the lab, Monod played a crucial role in shaping science policy and institutional governance. In 1971, he became the director of the Pasteur Institute, where he implemented reforms to modernize research practices and encourage interdisciplinary collaboration. His leadership emphasized rigor, creativity, and intellectual freedom—values he believed essential for scientific progress.

Monod was also an outspoken advocate for the role of science in society. He believed that rational thinking and empirical evidence should guide public decision-making, a stance that occasionally brought him into conflict with political and religious authorities. His critiques of dogma and pseudoscience were sharp, and he often warned against the dangers of ideology overriding evidence. Monod’s vision extended beyond academia; he saw science as a force for human progress, capable of addressing global challenges such as disease, hunger, and environmental crises.

Controversies and Philosophical Debates

Monod’s book "Chance and Necessity" (1970) was not only a scientific treatise but also a philosophical manifesto. In it, he argued that the universe was inherently devoid of predetermined purpose, and life arose from a combination of chance mutations and deterministic biochemical laws. This perspective clashed with teleological and religious worldviews, sparking widespread debate. Critics accused Monod of promoting a bleak, materialistic vision of existence, while others praised his intellectual honesty and defense of scientific rationality.

Despite the controversy, Monod’s ideas resonated with many scientists and thinkers who saw them as a bold reaffirmation of the Enlightenment’s values. His insistence that humanity must create its own meaning in an indifferent universe became a touchstone for secular humanism. Decades later, his arguments still influence discussions about the intersection of science, philosophy, and ethics.

Final Years and Lasting Impact

In his later years, Monod remained an active voice in scientific and intellectual circles, though his health began to decline due to complications from anemia. He passed away on May 31, 1976, but his legacy endured through the countless researchers who built upon his work. Monod had an extraordinary ability to bridge disciplines—moving seamlessly from biochemistry to genetics to philosophy—and his holistic approach continues to inspire scientists today.

His influence can be seen in fields ranging from synthetic biology to cancer research, where the principles of gene regulation he uncovered remain foundational. Institutions like the Jacques Monod Institute in France honor his contributions by fostering cutting-edge research in molecular and cellular biology. Monod’s life and work stand as a testament to the power of curiosity, courage, and reason in unlocking the mysteries of life.

Monod's Enduring Scientific Principles

The fundamental concepts Jacques Monod helped establish continue to shape modern biological research with remarkable precision. His work on allostery - the regulatory mechanism where binding at one site affects activity at another - remains a cornerstone of biochemistry and pharmacology. Today, approximately 60% of drugs target allosteric proteins, demonstrating the profound practical implications of Monod's theoretical framework. The molecular switches he studied in bacteria operate with similar logic in human cells, governing everything from hormone reception to neuronal signaling.

Recent advances in cryo-electron microscopy have revealed the intricate structural dynamics that Monod could only hypothesize about. High-resolution snapshots of the lactose repressor protein, first characterized by Monod's team, show extraordinary atomic-scale choreography that validates his prediction about conformational changes in regulatory proteins. Contemporary researchers continue discovering new layers of complexity in gene regulation that still adhere to the basic principles Monod established - feedback loops, threshold responses, and modular control systems that optimize cellular function.

The Evolution of His Ideas in Systems Biology

Monod's quantitative approach to studying biological systems anticipated the formal discipline of systems biology by several decades. His insistence on precise mathematical modeling of cellular processes - famously declaring "What's true for E. coli must be true for elephants" - set a standard for rigor in biological research. Modern systems biologists implementing Monod's philosophy have uncovered remarkable parallels between bacterial gene networks and human signaling pathways, proving many of his conceptual leaps correct.

The development of synthetic biology particularly owes a debt to Monod's work. Bioengineers routinely construct genetic circuits based on modified operons that function as biological logic gates, realizing Monod's vision of biology as an engineering discipline. Researchers at MIT recently created a complete synthetic version of the lac operon, replacing natural components with designed analogs while preserving its regulatory logic - a tribute to how thoroughly Monod decoded this system.

Philosophical Legacy in Contemporary Science

Monod's philosophical arguments in "Chance and Necessity" have gained renewed relevance in today's debates about artificial intelligence, complexity, and emergence. His insistence on distinguishing between objective knowledge and subjective values remains a guiding principle in scientific ethics. Modern theoretical biologists grappling with questions of consciousness and free will often find themselves rephrasing arguments first articulated by Monod about the interplay between deterministic laws and probabilistic events in living systems.

Neuroscientist Antonio Damasio acknowledged Monod's influence when proposing that homeostatic regulation in cells represents a primitive form of "value" that preceded nervous systems. This extension of Monod's concepts demonstrates how his ideas continue evolving across disciplinary boundaries. Similarly, researchers studying the origins of life now approach the chemical-to-biological transition using Monod's framework of molecular chance constrained by thermodynamic necessity.

Educational Initiatives and Institutional Impact

The Institut Jacques Monod in Paris stands as a living monument to his interdisciplinary vision, where physicists, chemists, and biologists collaborate on problems ranging from epigenetic inheritance to cell motility. Current director Jean-René Huynh notes that "Monod's spirit of asking fundamental questions while developing rigorous methods animates all our departments." Remarkably, over 40% of the institute's research straddles traditional discipline boundaries, fulfilling Monod's belief that major advances occur at intersections.

Educational programs inspired by Monod's approach have emerged worldwide. The Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory's summer courses teach gene regulation using Monod's heuristic of isolating principles from specific examples. At Stanford University, the BIO 82 course recreates classic Monod-Jacob experiments while adding modern genomic analysis, letting students experience both the historical foundations and current extensions of their work.

Unfinished Questions and Active Research Frontiers

Several mysteries Monod identified remain hot research topics. His observation that regulatory networks exhibit both robustness and sensitivity - now called the "Monod paradox" - continues challenging systems biologists. Teams at Harvard and ETH Zürich are testing whether this represents an evolutionary optimum or inevitable physical constraint using synthetic gene networks inserted into different host organisms.

The phenomenon of bistability that Monod observed in bacterial cultures now explains cellular decision-making in cancer progression and stem cell differentiation. Researchers at Memorial Sloan Kettering recently demonstrated how Monod-style positive feedback loops maintain drug resistance in leukemia cells, suggesting novel therapeutic approaches by targeting these ancient regulatory motifs.

Personal Legacy and Influence on Scientific Culture

Monod's analytical rigor coupled with creative intuition created a template for scientific excellence that mentees like Jeffey W. Roberts and Mark Ptashne carried forward. His famous quote "Science is the only culture that's truly universal" encapsulates his commitment to science as a humanistic enterprise. This vision manifests today in initiatives like the Human Cell Atlas project, which applies Monodian principles of systematic analysis to map all human cells.

Contemporary leaders often cite Monod's emphasis on methodological purity. CRISPR pioneer Jennifer Doudna keeps a copy of "Chance and Necessity" in her office, noting its influence on her thinking about scientific responsibility. Similarly, Nobel laureate François Englert credits Monod for demonstrating how theoretical boldness must be matched by experimental rigor - lessons that guided his Higgs boson research.

A Comprehensive Scientific Vision

Jacques Monod's career embodies the complete scientist - experimentalist, theorist, philosopher, and leader. From the molecular details of protein-DNA interactions to the grand questions of life's meaning, he demonstrated how science could illuminate multiple levels of reality. The Monod Memorial Lecture at the Collège de France annually highlights work that bridges these dimensions, from quantum biology to astrobiology.

As we enter an era of programmable biology and artificial life, Monod's insights provide both foundation and compass. His distinctions between invariance (genetic stability) and teleonomy (goal-directed function) help researchers navigate existential questions about synthetic organisms. The "Monod Test" has become shorthand for assessing whether biological explanations properly distinguish mechanistic causes from evolutionary origins.

Conclusion: An Ever-Evolving Legacy

Jacques Monod's influence continues expanding beyond what even he might have imagined. Recent discoveries about non-coding RNA regulation, phase separation in cells, and microbiomes all connect back to principles he established. As we decode more genomes but still struggle to predict phenotype from DNA sequence, Monod's warning about the complexity of regulation seems increasingly prophetic.

The ultimate tribute to Monod may be that his ideas have become so fundamental they're often taught without attribution - the highest form of scientific immortality. Yet returning to his original writings still yields fresh insights, proving that great science, like the operons he studied, remains perpetually relevant when grounded in universal truths about how life works at its core.

Craig Venter: The Visionary Scientist Who Revolutionized Genomics

Introduction: A Pioneer in Modern Biology

Craig Venter is one of the most influential and controversial figures in modern science. A biologist, entrepreneur, and visionary, Venter has played a pivotal role in decoding the human genome and pushing the boundaries of synthetic biology. His work has not only transformed our understanding of life but has also sparked ethical debates about the future of genetic engineering. This article explores his groundbreaking contributions, his unorthodox approach to science, and his relentless pursuit of innovation.

Early Life and Education

Born on October 14, 1946, in Salt Lake City, Utah, J. Craig Venter grew up in a working-class family. His early years were marked by a rebellious spirit and a fascination with the natural world. Initially, Venter struggled in school, but his passion for science eventually led him to pursue higher education. After serving as a Navy medical corpsman during the Vietnam War, he returned to the U.S. and earned a Ph.D. in physiology and pharmacology from the University of California, San Diego.

Venter's early career was characterized by a deep interest in molecular biology and genetics. He worked at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the 1980s, where he began developing techniques to accelerate DNA sequencing—a field that was still in its infancy. His innovative approach would later become the foundation for his revolutionary work in genomics.

The Race to Decode the Human Genome

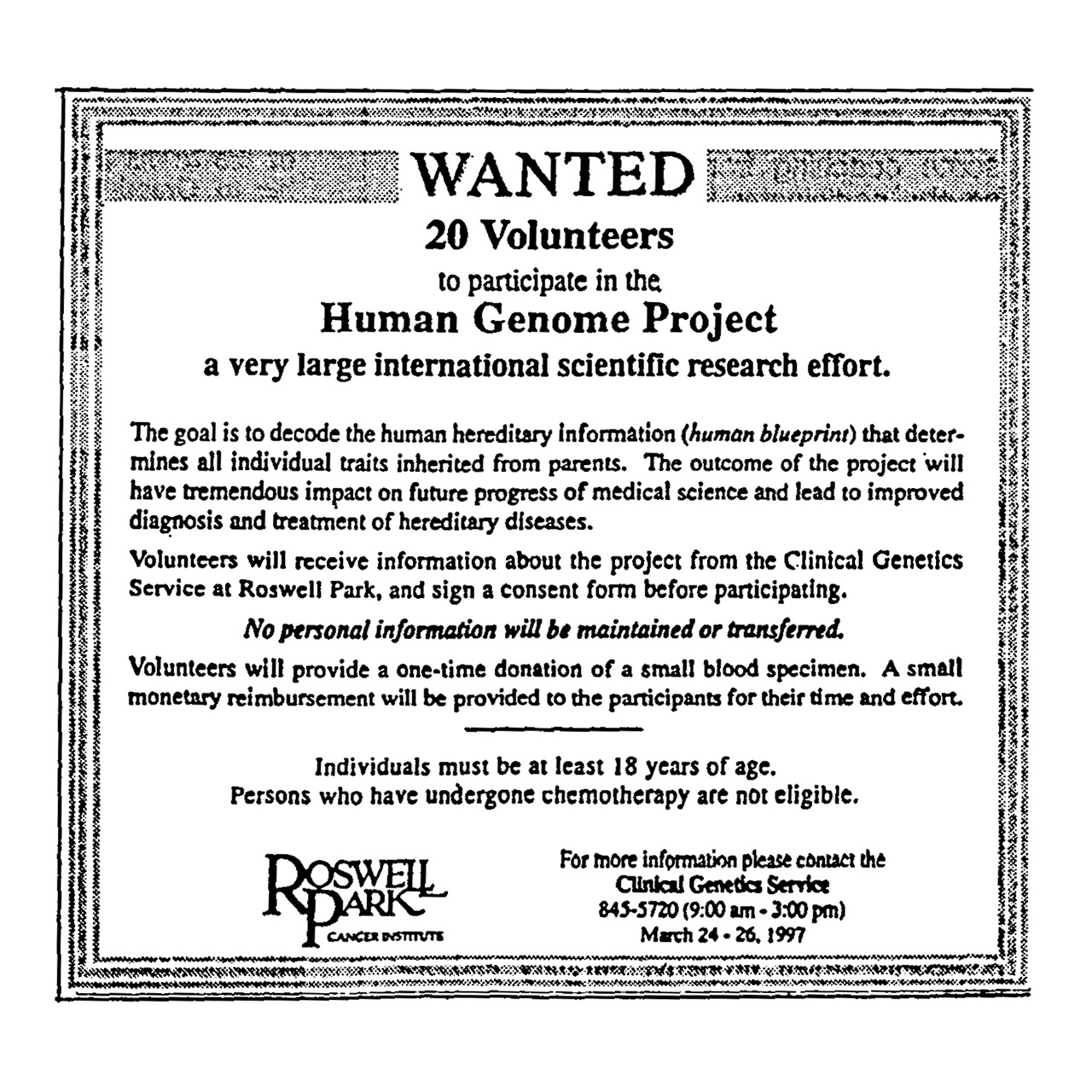

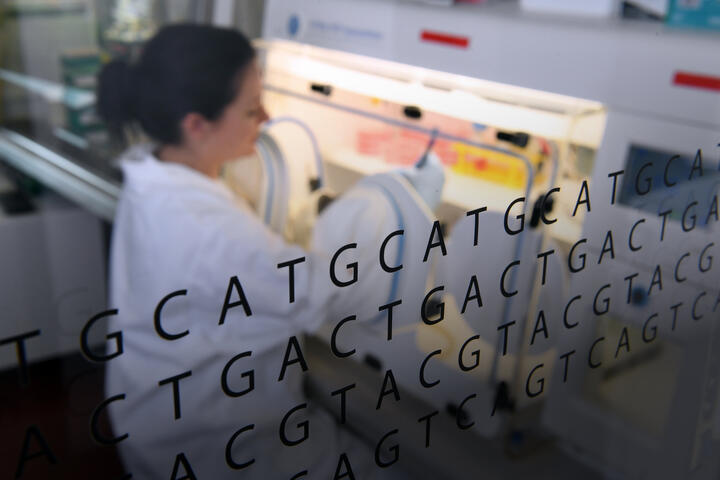

In the 1990s, the scientific community was embroiled in an intense competition to sequence the entire human genome. The Human Genome Project (HGP), a publicly funded international effort, aimed to map all human genes systematically. However, Venter believed the traditional methods were too slow and costly. Determined to find a faster solution, he pioneered a technique called "shotgun sequencing," which broke DNA into smaller fragments for rapid analysis and reassembly.

In 1998, Venter made headlines when he founded Celera Genomics, a private company backed by significant investment. His goal was to sequence the human genome before the HGP—and to do it at a fraction of the cost. The race between Celera and the public consortium became one of the most dramatic stories in scientific history. Despite fierce competition, both teams announced a draft sequence of the human genome in 2001, marking a monumental achievement for science.

Controversies and Ethical Debates

Venter’s aggressive, for-profit approach to genomics drew criticism from many in the scientific community. Some accused him of attempting to privatize the human genome, while others questioned the accuracy of his sequencing methods. The tension between public and private research models fueled debates about intellectual property, open science, and the commercialization of biological data.

Yet, Venter defended his methods, arguing that competition accelerated progress and that private investment was necessary for large-scale scientific breakthroughs. His work undeniably pushed genomics into the spotlight, paving the way for the personalized medicine revolution we see today.

Beyond the Human Genome: Synthetic Biology and New Frontiers

After Celera, Venter shifted his focus to synthetic biology—the design and construction of artificial life forms. In 2010, his team at the J. Craig Venter Institute achieved a historic milestone by creating the first synthetic bacterial cell. They synthesized a genome from scratch and successfully transplanted it into a recipient cell, effectively booting up a new form of life.

This breakthrough opened doors to revolutionary applications, from sustainable fuel production to disease-resistant crops. However, it also raised ethical concerns about the implications of "playing God" with life itself. Venter, ever the provocateur, embraced these discussions while continuing to explore the outer limits of biological engineering.

Entrepreneurial Ventures and Legacy

Beyond pure science, Venter has founded multiple companies, including Synthetic Genomics and Human Longevity Inc., focusing on genomics-driven healthcare and biotechnology solutions. His ventures aim to use genetic data to extend human lifespan, combat diseases, and address global challenges like climate change through bioengineered organisms.

As a scientist, entrepreneur, and thinker, Craig Venter remains a polarizing yet undeniably transformative figure. His relentless drive and willingness to challenge norms have reshaped modern biology, leaving a legacy that continues to influence research, medicine, and ethics in the 21st century.

The Impact of Venter’s Work on Genomic Medicine

Craig Venter’s contributions to genomics have fundamentally altered the landscape of modern medicine. By accelerating the sequencing of the human genome, his work enabled rapid advancements in personalized medicine—a field that tailors medical treatment to an individual’s genetic makeup. Today, doctors use genomic data to predict disease risks, customize drug therapies, and diagnose genetic disorders with unprecedented precision. Venter’s insistence on speed and efficiency helped make these tools accessible, reducing costs from billions of dollars to just a few hundred per genome.

Pharmacogenomics and Drug Development

One of the most immediate applications of Venter’s breakthroughs is in pharmacogenomics, the study of how genes affect a person’s response to drugs. His work laid the groundwork for identifying genetic markers that influence drug metabolism, allowing pharmaceutical companies to develop targeted therapies with fewer side effects. For example, cancer treatments like immunotherapy now incorporate genomic data to match patients with the most effective drugs, dramatically improving outcomes.

The Rise of Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Testing

Venter’s vision of democratizing genomics also paved the way for companies like 23andMe and AncestryDNA. By proving that rapid, cost-effective sequencing was possible, he indirectly spurred an industry that lets individuals explore their ancestry, detect hereditary conditions, and even uncover predispositions to diseases like Alzheimer’s. While these services have sparked debates about privacy and data security, their existence can be traced back to the technological leaps Venter championed.

Exploring the Microbiome and Environmental Genomics

Venter’s curiosity extended beyond human DNA into the vast, uncharted territory of microbial life. His Sorcerer II Expeditions, which circumnavigated the globe collecting marine microbial samples, revealed millions of new genes and thousands of species previously unknown to science. This research highlighted the critical role of microbes in Earth’s ecosystems, from regulating climate cycles to influencing human health.

The Human Microbiome Project

His findings contributed to the Human Microbiome Project, an initiative exploring how trillions of microbes in and on our bodies affect everything from digestion to immune function. Venter’s work showed that humans are, in many ways, superorganisms—hosting a complex microbial ecosystem that plays a vital role in our well-being. This insight has led to breakthroughs in probiotics, microbiome-based therapies, and even mental health research.

Environmental DNA (eDNA) and Conservation

Venter also pioneered environmental DNA (eDNA) sequencing, a technique that detects genetic material in soil, water, and air to monitor biodiversity without disturbing ecosystems. This method is now a cornerstone of conservation biology, allowing scientists to track endangered species, detect invasive organisms, and assess the health of fragile habitats. His ocean research, in particular, has been instrumental in understanding microbial contributions to carbon cycling and climate change mitigation.

Synthetic Biology: Creating Life in the Lab

Perhaps Venter’s most audacious endeavor was the creation of the first synthetic cell in 2010. His team synthesized the genome of Mycoplasma mycoides from scratch and implanted it into a recipient bacterial cell, effectively producing a life form controlled entirely by human-designed DNA. This achievement marked the dawn of synthetic biology—an era where organisms can be engineered for specific purposes, from biofuels to biodegradable plastics.

Applications in Industry and Sustainability

Venter founded Synthetic Genomics to commercialize these breakthroughs, targeting sectors like energy, agriculture, and medicine. His team engineered algae to produce biofuels, offering a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Other projects include designing bacteria that consume greenhouse gases or manufacture vaccines on demand. These innovations promise to address some of humanity’s most pressing challenges, including climate change and pandemics.

Ethical and Philosophical Questions

The creation of synthetic life raised profound ethical dilemmas. Critics argue that tinkering with life’s blueprint could have unintended consequences, such as engineered organisms escaping into the wild or being weaponized. Venter has engaged with these concerns head-on, advocating for strict regulatory frameworks while pushing the boundaries of what’s scientifically possible. His perspective is pragmatic: the risks, he argues, are outweighed by the potential benefits to humanity.

The Future According to Venter

Even in his 70s, Venter remains a forward-thinking innovator. His current ventures, like Human Longevity Inc., aim to extend human healthspan using AI-driven genomics. The company’s goal is to sequence one million human genomes, correlating genetic data with health outcomes to unlock secrets of aging and disease prevention. Meanwhile, his research into synthetic biology continues to explore radical possibilities, such as designing organisms capable of surviving on Mars.

The Digitization of Life

One of Venter’s most futuristic ideas is the concept of “biological teleportation”—digitizing DNA sequences and transmitting them across the globe to be reconstructed in labs. This could revolutionize medicine by enabling instant vaccine production during outbreaks or allowing astronauts to 3D-print medicines in space. While still speculative, the idea underscores his belief that biology is an information science, bound only by the limits of human ingenuity.

Inspiring the Next Generation

Beyond his research, Venter has become a vocal advocate for science education and entrepreneurship. He emphasizes the need for young scientists to think disruptively and embrace risk—much as he did. His memoir, A Life Decoded, and frequent public talks offer a blueprint for turning bold ideas into reality, cementing his role as a mentor to aspiring innovators.

As the second part of this article demonstrates, Venter’s influence spans medicine, environmental science, and synthetic biology. His willingness to challenge conventions and pursue high-risk, high-reward science continues to shape our world in ways we are only beginning to understand.

The Legacy of Craig Venter: Science, Controversy, and Unfinished Dreams

As one of the most prominent scientists of our time, Craig Venter's legacy extends far beyond his specific discoveries. His career represents a paradigm shift in how biological research is conducted, funded, and applied to real-world problems. What sets Venter apart is not just his scientific brilliance, but his unique ability to bridge academia, industry, and public policy—often stirring controversy while driving progress forward.

Championing Open Science vs. Commercial Interests

Venter's approach to science has always existed at the intersection of open inquiry and commercialization. While critics argue that his private ventures threatened the open-access ethos of the Human Genome Project, proponents highlight how he forced the scientific establishment to work faster and more efficiently. The tension between these two models continues today in debates over data sharing, patent rights, and AI-driven drug discovery. Venter's experiences provide valuable case studies on balancing commercial viability with scientific progress.

Interestingly, Venter has evolved his stance over time. After leaving Celera, he founded the nonprofit J. Craig Venter Institute, demonstrating his commitment to basic research. However, he maintains that intellectual property protections are necessary to incentivize expensive biomedical breakthroughs—a perspective that reflects his pragmatism and firsthand experience in turning discoveries into tangible benefits.

Venter's Vision for the Future of Humanity

Extending the Human Lifespan

Through Human Longevity Inc., Venter aims to radically extend the healthy human lifespan by decoding the molecular secrets of aging. His ambitious project to sequence one million genomes seeks to identify biomarkers that predict longevity and develop personalized interventions. This research could lead to breakthroughs in regenerative medicine, with potential treatments for age-related diseases like Alzheimer's and cardiovascular disorders.

Perhaps more provocatively, Venter has theorized about using synthetic biology to enhance human capabilities. In interviews, he's speculated about engineering humans to be radiation-resistant for space travel or creating specialized immune systems that could defeat any virus—ideas that blur the line between therapy and enhancement.

Space Exploration and Astrobiology

Venter's work has always extended beyond Earth. His interest in extremophiles—organisms that thrive in harsh environments—has implications for finding life elsewhere in the universe. NASA has collaborated with his teams to develop DNA sequencers for the International Space Station and future Mars missions.

Most strikingly, Venter has proposed using synthetic biology to terraform Mars. By engineering microorganisms that could produce oxygen or breakdown Martian regolith, he envisions creating habitable environments before human arrival. This futuristic application demonstrates how his work in synthetic biology could fundamentally alter humanity's relationship with the cosmos.

The Ethical Minefield: Venter's Most Controversial Ideas

Playing God or Advancing Science?