Armand Hippolyte Louis Fizeau: Pioneering French Physicist and Astronomer

The Early Life and Education of Armand Fizeau

Armand Hippolyte Louis Fizeau was born on August 23, 1819, in Châtenay (now part of Montmartre), Paris, France. His father, Claude Fizayeau, was a physician who practiced at the Hotel-Dieu hospital in Paris, and his mother was Rose Lefèbvre. Despite coming from a modest background, Fizeau showed early signs of intellectual brilliance, which became evident during his childhood.

A Career Path in Physics and Astronomical Discoveries

Fizayeau pursued his primary education at Lycee Charlemagne, graduating in 1839. His academic prowess did not go unnoticed; he demonstrated exceptional skills in both mathematics and physics, which led him towards academia. In 1841, Fizeau started working as an assistant at the Paris Observatory under Leon Foucault. It was here that he began to delve into precision measurements, particularly in the realm of optics and astronomy, laying down the foundation for several groundbreaking discoveries.

Contributions in Optics and the Speed of Light

The Fizeau Experiment: Measuring the Speed of Light

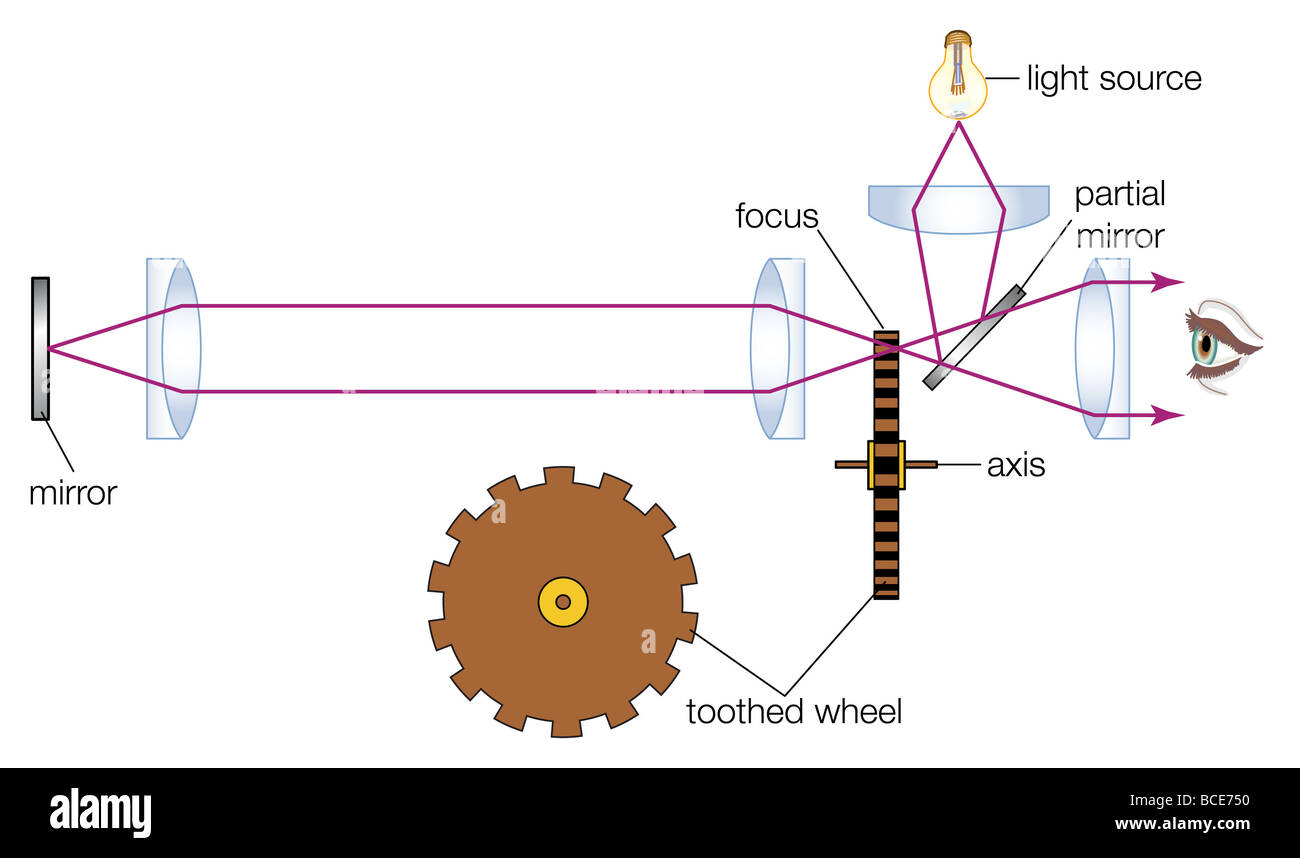

In one of his most famous works, Fizeau conducted what is known as the "Fizeau experiment" to measure the speed of light through moving water. This experiment not only provided a more accurate measurement of the speed of light but also confirmed the wave theory of light. Here's how the experiment worked:

- Setup: A beam of light was directed towards a mirror placed some kilometers away.

- Water Wheel: Between the light source and the mirror, a rapidly rotating glass disk with holes was placed. The disk was constructed such that holes would move in time with the rotation rate.

- Data Collection: When the holes in the disc were aligned with the beam of light passing through, the light would travel to the mirror, reflect back, pass through another hole, and reach the photometer. Adjusting the rotation rate allowed for precise measurement of the speed of light when the hole alignment was just right to block the returning light.

Fizeau's first result, published in 1851, gave a value of 315,000 km/s, which was much closer to the modern value of approximately 299,792 km/s. This experiment significantly improved upon the previous estimates made by Pierre-Simon Laplace and Jean-Bernard Fourier, providing new insights into the nature of light propagation.

Explorations in Refractive Indices

Fizeau- Foucault Apparatus: Measuring Refractive Indices

Fizeau's contributions to physics extended beyond simply measuring the speed of light. He also developed the "Fizeau-Foucault apparatus," which was used to determine refractive indices of various materials accurately. Using this apparatus, he was able to measure the refractive index of diamond, obtaining a value of 2.42 in 1847. This was one of the most precise measurements of its time.

The apparatus consisted of a series of prisms and a lens system. By carefully adjusting the position of the lenses and measuring the resulting path lengths, Fizeau could calculate the refractive index of different substances with high precision. This method revolutionized the way scientists approached the measurement of refractive indices, paving the way for further advancements in optics.

Scientific Instruments and Innovations

Bright-Line Spectroscope

Another significant contribution Fizeau made to spectroscopy was the development of the bright-line spectroscope. This innovation, introduced in the late 1850s, allowed for more precise separation and identification of spectral lines. Unlike earlier spectrometers, Fizeau's design produced brighter and clearer spectra, making it easier for astronomers to analyze the composition of stars and other celestial bodies.

The bright-line spectroscope was based on a prism system that separated the white light into its constituent colors, followed by a diffraction grating that produced a sharper and more defined spectrum. This tool greatly enhanced the accuracy and reliability of astronomical measurements, enabling a better understanding of the fundamental properties of matter and energy.

Legacy and Recognition

Fizeau's work had a profound impact on the scientific community. His discoveries in optics and his innovations in instruments played crucial roles in advancing the field. His methodologies and apparatuses became standards used in research institutions worldwide.

Throughout his career, Fizeau received numerous accolades. In 1853, he was elected to the Academie des Sciences, becoming a full member, a testament to his contributions to science. Later, he was awarded the Rumford Medal by the Royal Society for his distinguished work on the speed of light, further highlighting his influence in the scientific world.

Conclusion

Armand H. L. Fizeau was not merely a pioneer in the field of physics but an innovator who left an indelible mark on scientific discourse. His experiments, inventions, and discoveries continue to influence contemporary research in optics, astronomy, and spectroscopy. Future generations of scientists stand on the shoulders of giants like Fizeau, who dared to question conventional wisdom and boldly explore the mysteries of the universe.

Further Contributions to Physics and Astronomy

Following his groundbreaking work on the speed of light, Fizeau made significant contributions to the field of physics through his research on heat conduction. In a series of experiments conducted in 1866, he measured the rate at which heat travels through a metal rod. Fizeau found that heat conducted along the rod traveled at about one-third the speed of light, offering another confirmation of the wave nature of heat. This discovery expanded the understanding of thermal phenomena, providing a more comprehensive framework for thermal physics.

Fizeau also contributed to the field of magnetism. In 1883, he published a paper describing a method to measure the magnetic field produced by a current-carrying wire. This technique involved using a magnetic needle placed in a circuit and measuring the deflection caused by the magnetic field. Fizeau's work in this area laid the groundwork for further studies in electromagnetic theory. His contributions were particularly significant in the context of understanding the relationship between electrical currents and magnetic fields, which are fundamental concepts in modern physics.

Collaborations and Collaborators

Throughout his career, Fizeau collaborated with several notable scientists, including Jean-Claude Biot, Claude Pouillet, and Hippolyte Fizeau (his brother). His collaborations enhanced the scope and impact of his research. One of his closest collaborators was Jean-Claude Biot, a prominent French physicist who shared Fizeau's interest in precision experiments. Through their joint work, they made significant contributions to the study of light and electricity, advancing the methodologies and techniques used in these fields.

Teaching and Mentorship

In addition to his experimental work, Fizeau played a critical role in the academic community as a teacher and mentor. In 1863, he was appointed as a professor at the Ecole Polytechnique, where he taught physics. His lectures and teaching approach were highly regarded, and he inspired many of his students to pursue careers in science. One of his notable students was Pierre Curie, the future Nobel laureate who would go on to make significant contributions to the field of physics, particularly in the discovery of radioactivity.

Publications and Scholarly Contributions

Fizeau was a prolific author who published numerous papers and books that detailed his experimental methods, findings, and theoretical insights. His book, "Traité de Physique," published in 1874, is a comprehensive work that covers a wide range of topics in physics, including mechanics, heat, and sound. The book reflects Fizeau's deep understanding of the principles of physics and serves as a valuable resource for students and researchers.

In addition to "Traité de Physique," Fizeau published several other significant works, such as "Le Système du Monde" in 1876, which delved into the structure and evolution of the universe. These publications not only disseminated knowledge but also established Fizeau as a respected authority in his field.

Nobel Prize Nomination

Fizeau's contributions were recognized by his peers, and his name has been associated with several important physical units. In 1881, he was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Physics, which at the time was not yet awarded. Although he did not win the prize, his nomination highlights the high regard in which he was held within the scientific community. The metric unit of velocity, the Fizeau, is named after him, honoring his groundbreaking research on the speed of light.

Legacy and Impact on Science Education2>

Fizeau's legacy extends beyond his specific contributions to science. His emphasis on precise experimentation and rigorous data analysis has had a lasting impact on science education and research methodologies. The scientific community continues to benefit from the standardized techniques and experimental approaches pioneered by Fizeau, ensuring that today's research builds upon a robust foundation of well-tested methods.

Final Years and Legacy2>

Armand H. L. Fizeau led a life characterized by intellectual curiosity and relentless pursuit of scientific truth. After retiring from the Academie des Sciences in 1885, he remained active in scientific discourse until his death on October 18, 1896, in Bougival, France. His contributions to science have stood the test of time, and his legacy continues to inspire new generations of scientists.

Through his pioneering work in optics, thermodynamics, and magnetism, Fizeau played a crucial role in shaping the modern understanding of physical phenomena. His meticulous experiments, innovative instruments, and dedication to scientific inquiry have cemented his place as one of the most impactful scientists in the history of physics. Fizeau's enduring influence serves as a testament to the power of scientific exploration and the importance of precision in scientific research.

Modern Relevance of Fizeau's Work

Even today, the legacy of Armand Fizeau remains relevant in modern scientific research. His methods and findings have not only served as a basis for contemporary experiments but also continue to inspire new areas of inquiry in physics. For example, the principles he established in the Fizeau experiment are still used in sophisticated optical instruments such as interferometers, which are crucial in precision measurements and medical diagnostics.

Moreover, Fizeau's contributions to the measurement of the speed of light have been foundational in the development of modern time standardization. The use of optical fibers and laser technology, which owe much to the principles he elucidated, are critical in the global synchronization of time and the precise calibration of communication systems. In the realm of quantum physics, the precision methods Fizeau pioneered continue to influence the development of quantum sensors and metrology.

Influence on Modern Physics

The work of Fizeau has had a ripple effect on various subfields of modern physics. His experiments on the speed of light and refraction indices have inspired researchers to develop and refine more advanced techniques for measuring physical constants. For instance, the use of modern laser spectroscopy, a direct descendant of Fizeau's spectroscope, has enabled the accurate determination of atomic and molecular structures, contributing to our understanding of chemical bonds and quantum phenomena.

Moreover, Fizeau's emphasis on precision and reliability has influenced the design of experimental setups in contemporary physics. Modern scientists often use principles derived from Fizeau's work to test hypotheses and validate theories. The meticulousness and rigor required in scientific experimentation, as exemplified by Fizeau, remain essential components of scientific progress.

Public Outreach and Popular Science

While Fizeau's primary contributions were in the realm of experimental physics, his work also extended to public outreach and popular science. He was a vocal advocate for the importance of science in everyday life and regularly contributed to scientific journals and publications. His efforts to make complex scientific concepts accessible to the general public contributed to the broader acceptance and understanding of scientific principles.

Fizeau's public lectures and writings helped popularize the wonders of modern physics. His book "Traité de Physique" was not only a scholarly work but also a popularized explanation of physical phenomena, making it accessible to a wider audience. This approach has inspired generations of scientists to communicate and disseminate their findings effectively, contributing to the broader dissemination of scientific knowledge.

Honors and Memorials2>

To honor Armand Fizeau's contributions, several memorials have been established in his name. The Fizeau Medal, which is awarded by the French National Academy of Sciences, recognizes outstanding contributions to the physical sciences. Additionally, the city of Châtenay, where he was born, has a street named after him, a nod to the importance of his scientific legacy to the community where he first explored his intellectual prowess.

Conclusion2>

In reflection, Armand H. L. Fizeau stands as a testament to the enduring impact of dedicated scientific inquiry. His pioneering work in optics, thermodynamics, and magnetism has not only advanced the field of physics but also influenced numerous other scientific disciplines. Fizeau's legacy is a reminder of the importance of precision and innovation in scientific research. As the scientific community continues to build upon the foundation laid by Fizeau, his contributions remain a source of inspiration and a vital part of the scientific heritage.

Fizeau's contributions to science serve as a model for future scientists, emphasizing the value of rigorous experimentation and the importance of precision in the scientific enterprise. His work continues to inform and inspire new generations of scientists, ensuring that the legacy of Armand H. L. Fizeau endures in the annals of scientific history.

Ptolemy: The Ancient Scholar Who Mapped the Heavens and the Earth

Introduction

Claudius Ptolemy, commonly known simply as Ptolemy, was one of the most influential scholars of the ancient world. A mathematician, astronomer, geographer, and astrologer, his works shaped scientific thought for over a millennium. Living in Alexandria during the 2nd century CE, Ptolemy synthesized and expanded upon the knowledge of his predecessors, creating comprehensive systems that dominated European and Islamic scholarship until the Renaissance. His contributions to astronomy, geography, and the understanding of the cosmos left an indelible mark on history.

Life and Historical Context

Little is known about Ptolemy’s personal life, but historical evidence suggests he was active between 127 and 168 CE. Alexandria, then part of Roman Egypt, was a thriving center of learning, home to the famed Library of Alexandria, which housed countless scrolls of ancient wisdom. Ptolemy benefited from this intellectual environment, drawing from Greek, Babylonian, and Egyptian sources to develop his theories.

His name, Claudius Ptolemaeus, indicates Roman citizenship, possibly granted to his family by Emperor Claudius or Nero. Though his ethnicity remains uncertain—whether Greek, Egyptian, or a mix—his works were written in Greek, the scholarly language of the time.

Ptolemy’s Astronomical Contributions

Ptolemy’s most famous work, the AlmagestMathematike Syntaxis), became the cornerstone of astronomy for centuries. In it, he synthesized the ideas of earlier astronomers like Hipparchus and introduced a sophisticated mathematical model of the universe.

The Ptolemaic System

Ptolemy’s geocentric model placed Earth at the center of the universe, with the Sun, Moon, planets, and stars orbiting around it in complex paths. To explain the irregular movements of planets (such as retrograde motion), he introduced mathematical concepts like epicycles—small circles within larger orbits—and eccentric orbits. While his system was later challenged by Copernicus’ heliocentric model, it provided remarkably accurate predictions for its time.

Star Catalog and Constellations

In the Almagest, Ptolemy also compiled a star catalog, listing over 1,000 stars with their positions and magnitudes. Many of the 48 constellations he described are still recognized today in modern astronomy.

Ptolemy’s Geographical Legacy

Beyond astronomy, Ptolemy made lasting contributions to geography through his work Geographia. This treatise compiled extensive knowledge about the known world, combining maps with coordinates based on latitude and longitude—a revolutionary concept at the time.

Mapping the World

Ptolemy’s maps, though flawed by modern standards due to limited exploration, provided the most detailed geographical reference of the ancient world. He estimated Earth’s size, though his calculations were smaller than Eratosthenes’ earlier (and more accurate) measurements. Despite errors, his methodology laid the groundwork for later cartographers.

Influence on Exploration

Centuries later, during the Age of Discovery, Ptolemy’s Geographia regained prominence. Explorers like Columbus relied on his maps, though some inaccuracies—such as an underestimated Earth circumference—may have influenced voyages based on miscalculations.

Ptolemy and Astrology

Ptolemy also contributed to astrology with his work Tetrabiblos ("Four Books"). While modern science dismisses astrology, in antiquity, it was considered a legitimate field of study. Ptolemy sought to systematize astrological practices, linking celestial movements to human affairs in a structured way.

The Role of Astrology in Antiquity

Unlike modern horoscopes, Ptolemy’s approach was more deterministic, emphasizing celestial influences on climate, geography, and broad human tendencies rather than personal fate. His work remained a key astrological reference well into the Renaissance.

Criticism and Legacy

While Ptolemy’s models were groundbreaking, they were not without flaws. His geocentric system, though mathematically elegant, was fundamentally incorrect. Later astronomers like Copernicus and Galileo would dismantle it, leading to the Scientific Revolution.

Yet, Ptolemy’s genius lay in his ability to synthesize and refine existing knowledge. His works preserved and transmitted ancient wisdom to future generations, bridging gaps between civilizations. Even when his theories were superseded, his methodological rigor inspired later scientists.

Conclusion (Part 1)

Ptolemy stands as a towering figure in the history of science, blending meticulous observation with mathematical precision. His geocentric model and maps may no longer hold scientific weight, but his contributions laid essential groundwork for astronomy, geography, and even early astrology. In the next part, we will delve deeper into the technical aspects of his astronomical models, their historical reception, and how later scholars built upon—or challenged—his ideas. Stay tuned as we continue exploring the enduring legacy of Claudius Ptolemy.

The Technical Brilliance of Ptolemy’s Astronomical Models

Ptolemy’s geocentric model was not merely a philosophical assertion but a meticulously crafted mathematical system designed to explain and predict celestial phenomena. His use of epicycles, deferents, and equants demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of geometry and trigonometry, allowing him to account for the irregularities in planetary motion that had puzzled earlier astronomers.

Epicycles and Deferents

At the heart of Ptolemy’s model were two principal components: the deferent, a large circular orbit around the Earth, and the epicycle, a smaller circle on which the planet moved while simultaneously revolving around the deferent. This dual-motion concept elegantly explained why planets sometimes appeared to move backward (retrograde motion) when observed from Earth. Though later proven unnecessary in a heliocentric framework, this system was remarkably accurate for its time.

The Equant Controversy

One of Ptolemy’s more controversial innovations was the equant point, a mathematical adjustment that allowed planets to move at varying speeds along their orbits. Instead of moving uniformly around the center of the deferent, a planet’s angular speed appeared constant when measured from the equant—a point offset from Earth. While this preserved the principle of uniform circular motion (sacred in ancient Greek astronomy), it also introduced asymmetry, troubling later astronomers like Copernicus, who sought a more harmonious celestial mechanics.

Ptolemy vs. Earlier Greek Astronomers

Ptolemy was indebted to earlier astronomers, particularly Hipparchus of Nicaea (2nd century BCE), whose lost works likely inspired much of the Almagest. However, Ptolemy refined and expanded these ideas with greater precision, incorporating Babylonian eclipse records and improving star catalogs. His work was less about radical innovation and more about consolidation—turning raw observational data into a cohesive, predictive framework.

Aristotle’s Influence

Ptolemy’s cosmology also embraced Aristotelian physics, which posited that celestial bodies were embedded in nested crystalline spheres. While Ptolemy’s mathematical models did not strictly depend on this physical structure, his alignment with Aristotle helped his system gain philosophical legitimacy in medieval Europe.

Transmission and Influence in the Islamic World

Ptolemy’s works did not fade after antiquity. Instead, they were preserved, translated, and enhanced by scholars in the Islamic Golden Age. The Almagest (from the Arabic al-Majisti) became a foundational text for astronomers like Al-Battani and Ibn al-Haytham, who refined his planetary tables and critiqued his equant model.

Critiques and Improvements

Islamic astronomers noticed discrepancies in Ptolemy’s predictions, particularly in Mercury’s orbit. In the 13th century, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi developed the Tusi couple, a mathematical device to generate linear motion from circular motions, which later influenced Copernicus. Meanwhile, Ibn al-Shatir’s 14th-century models replaced Ptolemy’s equant with epicycles that adhered more closely to uniform circular motion—anticipating elements of Copernican theory.

Ptolemy’s Geography: Achievements and Errors

Returning to Ptolemy’s Geographia, his ambition was nothing short of mapping the entire oikoumene (inhabited world). Using latitude and longitude coordinates, he plotted locations from the British Isles to Southeast Asia—though with gaps and distortions due to limited traveler accounts and instrumental precision.

Key Features of Geographia

1. Coordinate System: Ptolemy’s grid of latitudes and longitudes was revolutionary, though his prime meridian (passing through the Canary Islands) and exaggerated landmass sizes (e.g., Sri Lanka) led to errors.

2. Projection Techniques: He proposed methods to represent the spherical Earth on flat maps, foreshadowing modern cartography. Unfortunately, his underestimation of Earth’s circumference (based on Posidonius’ flawed calculations) persisted for centuries.

The Silk Road and Beyond

Ptolemy’s references to the Silk Road and lands east of Persia reveal the limits of Greco-Roman geographical knowledge. His “Serica” (China) and “Sinae” (unknown eastern regions) were vague, yet his work tantalized Renaissance explorers seeking routes to Asia.

Ptolemaic Astrology in Depth

The Tetrabiblos positioned astrology as a “science” of probabilistic influences rather than absolute fate. Ptolemy argued that celestial configurations affected tides, weather, and national destinies—aligning with Aristotle’s notion of celestial “sublunar” influences.

The Four Elements and Zodiac

Ptolemy correlated planetary positions with the four classical elements (fire, earth, air, water) and zodiac signs. For example:

- Saturn governed cold and melancholy (earth/water).

- Mars ruled heat and aggression (fire).

His system became standard in medieval and Renaissance astrology, despite criticism from skeptics like Cicero.

Medieval Europe: Ptolemy’s Renaissance

After centuries of neglect in Europe (where much Greek science was lost), Ptolemy’s works re-entered Latin scholarship via Arabic translations in the 12th century. The Almagest became a university staple, and geocentric cosmology was enshrined in Catholic doctrine—partly thanks to theologians like Thomas Aquinas, who reconciled Ptolemy with Christian theology.

Challenges from Within

Even before Copernicus, cracks appeared in the Ptolemaic system. The Alfonsine Tables (13th century), based on Ptolemy, revealed inaccuracies in planetary positions. Astronomers like Peurbach and Regiomontanus attempted revisions, but the model’s complexity grew untenable.

Conclusion (Part 2)

Ptolemy’s legacy is a paradox: his models were both brilliant and fundamentally flawed, yet they propelled scientific inquiry forward. Islamic scholars refined his astronomy, while European explorers grappled with his geography. In the next installment, we’ll explore how the Copernican Revolution dismantled Ptolemy’s cosmos—and why his influence persisted long after heliocentrism’s triumph.

The Copernican Revolution: Challenging Ptolemy’s Universe

When Nicolaus Copernicus published De revolutionibus orbium coelestium in 1543, he initiated one of history's most profound scientific revolutions. His heliocentric model didn't just rearrange the cosmos - it fundamentally challenged the Ptolemaic system that had dominated Western astronomy for nearly 1,400 years. Yet interestingly, Copernicus himself remained deeply indebted to Ptolemy's methods, retaining epicycles (though fewer) and uniform circular motion in his own calculations.

Why Ptolemy Couldn't Be Ignored

The transition from geocentrism to heliocentrism wasn't simply about Earth's position but represented a complete rethinking of celestial mechanics. However:

- Copernicus still needed Ptolemy's mathematical framework to make his model work

- Many of the same observational data (often Ptolemy's own) were used

- The initial heliocentric models were no more accurate than Ptolemy's at predicting planetary positions

Tycho Brahe's Compromise

The Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) proposed an intriguing geo-heliocentric hybrid that:

1. Kept Earth stationary at the center

2. Had other planets orbit the Sun

3. Used Ptolemaic-level precision in measurements

This system gained temporary favor as it avoided conflict with Scripture while incorporating Copernican elements.

Galileo's Telescope: The Final Blow

Galileo Galilei's celestial observations in 1609-1610 provided the smoking gun against Ptolemaic cosmology:

- Jupiter's moons proved not everything orbited Earth

- Venus' phases matched Copernican predictions

- Lunar mountains contradicted perfect celestial spheres

The Church's Dilemma

While Galileo's discoveries supported heliocentrism, the Catholic Church had formally adopted Ptolemy's system as doctrinal truth after Aquinas' synthesis. This led to:

- The 1616 condemnation of Copernicanism

- Galileo's famous trial in 1633

It would take until 1822 for the Church to accept heliocentrism officially.

Kepler's Breakthrough: Beyond Ptolemy's Circles

Johannes Kepler's laws of planetary motion (1609-1619) finally explained celestial mechanics without Ptolemy's complex devices:

1. Elliptical orbits replaced epicycles

2. Planets sweep equal areas in equal times

3. The period-distance relationship provided physical explanations

Remarkably, Kepler initially tried to preserve circular motion, showing how deeply rooted Ptolemy's influence remained in astronomical thought.

Legacy in the Enlightenment and Beyond

Even after being scientifically superseded, Ptolemy's work continued to influence scholarship:

- Isaac Newton studied the Almagest

- 18th-century astronomers referenced his star catalog

- Modern historians still analyze his observational techniques

The Ptolemaic Revival in Scholarship

Recent scholarship has reassessed Ptolemy's contributions more fairly:

- Recognizing his observational accuracy given limited instruments

- Appreciating his mathematical ingenuity

- Understanding his role in preserving ancient knowledge

Ptolemy's Enduring Influence on Geography

While Ptolemy's astronomical models were replaced, his geographical framework proved more durable:

- The latitude/longitude system remains fundamental

- His map projections influenced Renaissance cartography

- Modern digital mapping owes conceptual debts to his coordinate system

Rediscovery of the Geographia

The 15th-century rediscovery of Ptolemy's Geographia had immediate impacts:

- Printed editions with maps influenced Christopher Columbus

- Inspired new exploration of Africa and Asia

- Standardized place names across Europe

Ptolemy in Modern Science and Culture

Ptolemy's name and concepts persist in surprising ways:

- The Ptolemaic system appears in planetariums as an educational tool

- "Ptolemaic" describes any outdated but once-dominant paradigm

- Features on the Moon and Mars bear his name

Historical Lessons from Ptolemy's Story

Ptolemy's legacy offers valuable insights about scientific progress:

1. Even "wrong" theories can drive knowledge forward

2. Scientific revolutions don't happen in jumps but through cumulative steps

3. Methodology often outlasts specific conclusions

Conclusion: The Timeless Scholar

Claudius Ptolemy represents both the power and limits of human understanding. For over a millennium, his vision of an Earth-centered cosmos organized the way civilizations saw their place in the universe. While modern science has proven his astronomical models incorrect, we must recognize:

- His work preserved crucial knowledge through the Dark Ages

- His methods laid foundations for the Scientific Revolution

- His geographical system transformed how we conceive space

The very fact that we still study Ptolemy today - not just as historical curiosity but as a milestone in human thought - testifies to his unique position in the story of science. In an age of satellites and space telescopes, we stand on the shoulders of this Alexandrian giant who first sought to map both the earth and heavens with mathematical precision. His legacy reminds us that scientific truth is always evolving, and that today's certainties may become tomorrow's historical footnotes.

George Ellery Hale: The Visionary Astronomer Who Revolutionized Astrophysics

Early Life and Passion for Astronomy

George Ellery Hale was born on June 29, 1868, in Chicago, Illinois, into a prosperous family that encouraged his intellectual curiosity. From a young age, Hale displayed a deep fascination with the cosmos. By the time he was a teenager, he had already built his own telescope and begun conducting astronomical observations. His father, William Hale, a successful elevator manufacturer, recognized his son's passion and supported his scientific pursuits by providing him with books and equipment.

Hale's early education took place at the Oakland Public School in Chicago before he attended the Allen Academy. He later enrolled at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he studied physics and engineering. While at MIT, Hale continued his astronomical work, refining his skills in spectroscopy—a field that would later define his career. His early observations of the Sun and stars laid the groundwork for his future contributions to astrophysics.

Founding the Yerkes Observatory

One of Hale’s most significant early achievements was the establishment of the Yerkes Observatory in Wisconsin. After graduating from MIT in 1890, Hale sought funding to build a world-class observatory equipped with the largest refracting telescope ever constructed. He secured financial backing from businessman Charles Tyson Yerkes, and in 1897, the Yerkes Observatory was completed, featuring a 40-inch refracting telescope.

Under Hale’s leadership, Yerkes became a hub for cutting-edge astronomical research. He recruited renowned scientists, such as Edwin Frost and Sherburne Wesley Burnham, to conduct observations and advance the study of stellar spectra. Hale himself made important contributions, particularly in solar astronomy, by developing new techniques to analyze the Sun’s chemical composition and magnetic fields.

Pioneering Solar Research

Hale was particularly intrigued by the Sun, recognizing it as a key to understanding stellar processes. His work in solar spectroscopy led to the discovery of the Zeeman effect in sunspots—the splitting of spectral lines due to magnetic fields. This breakthrough confirmed that sunspots were regions of intense magnetic activity, fundamentally altering astronomers’ understanding of the Sun’s behavior.

In 1904, Hale invented the spectroheliograph, an instrument that allowed detailed study of the Sun’s surface by capturing images in specific wavelengths of light. This invention revolutionized solar astronomy, enabling scientists to observe solar phenomena such as prominences and flares with unprecedented clarity. His relentless pursuit of innovation earned him recognition as one of the foremost solar physicists of his time.

The Birth of Mount Wilson Observatory

Despite the success of Yerkes, Hale recognized the limitations of operating an observatory in the Midwest, where weather conditions often hindered observations. Seeking clearer skies, he turned his attention to Southern California, where he established the Mount Wilson Observatory in 1904. Located in the San Gabriel Mountains near Pasadena, Mount Wilson offered ideal atmospheric conditions for astronomical research.

Hale envisioned Mount Wilson as a center for transformative discoveries. He spearheaded the construction of groundbreaking telescopes, including the 60-inch reflector completed in 1908. At the time, it was the largest operational telescope in the world. With this instrument, astronomers could observe fainter and more distant celestial objects than ever before, expanding humanity’s understanding of the universe.

The Hale Solar Laboratory and Further Innovations

Never one to rest on his laurels, Hale continued pushing the boundaries of astronomical technology. In 1923, he established the Hale Solar Laboratory in Pasadena, where he refined spectroscopic techniques and conducted pioneering research on solar magnetism. His work laid the foundation for modern solar physics, influencing generations of astronomers.

Hale also played a crucial role in the development of the 100-inch Hooker Telescope at Mount Wilson, completed in 1917. This telescope revolutionized astronomy by enabling Edwin Hubble, one of Hale’s protégés, to discover evidence of galaxies beyond the Milky Way—a revelation that reshaped cosmological theories.

Legacy and Later Years

Beyond his scientific achievements, Hale was a skilled organizer and advocate for scientific collaboration. He played a key role in founding the International Union for Cooperation in Solar Research (later the International Astronomical Union) and helped establish the National Research Council to promote scientific progress.

Despite suffering from deteriorating health in his later years, Hale remained deeply involved in astronomical projects. He envisioned an even more powerful telescope—the 200-inch Palomar Observatory telescope—though he did not live to see its completion in 1948. Nevertheless, his relentless vision and leadership ensured that astronomy advanced dramatically during his lifetime.

George Ellery Hale passed away on February 21, 1938, leaving behind a legacy that transformed astrophysics and observational astronomy. His relentless curiosity, technical ingenuity, and dedication to collaboration continue to inspire scientists today.

(First part of the article ends here. Awaiting your prompt to continue.)

The Palomar Observatory and the 200-Inch Telescope

Though George Ellery Hale did not live to see its completion, his vision for the Palomar Observatory and its colossal 200-inch telescope became one of his most enduring legacies. The project began in 1928 when Hale secured funding from the Rockefeller Foundation, recognizing that even the 100-inch Hooker Telescope at Mount Wilson had limitations in probing the farthest reaches of the universe. The new telescope, named the Hale Telescope in his honor, was an engineering marvel that pushed the boundaries of what was technologically possible.

The construction of the telescope’s massive mirror alone was a monumental challenge. Corning Glass Works was commissioned to create the unnaturally large glass disk, which required multiple attempts due to the difficulties of casting and cooling such a massive piece of optical glass without flaws. After years of painstaking work, the mirror was successfully completed, polished to near-perfection, and transported across the country in a carefully orchestrated journey to California’s Palomar Mountain.

After delays caused by World War II, the Hale Telescope was finally inaugurated in 1948, a decade after Hale’s death. It remained the largest effective telescope in the world until the construction of the Soviet BTA-6 in 1975 and continued to produce groundbreaking discoveries for decades. Astronomers used it to detect quasars, study galaxy formation, and refine the understanding of the expanding universe—all subjects that had been close to Hale’s heart.

Contributions to Astrophysics and Spectroscopy

Hale was not just a builder of telescopes; he was a pioneer in the field of astrophysics, particularly in the study of stellar and solar magnetic fields. His early discovery of magnetic fields in sunspots (via the Zeeman effect) was revolutionary, proving that the Sun was not just a static ball of gas but a dynamic body with complex electromagnetic activity. His work laid the groundwork for modern solar physics and established spectroscopy as one of the most important tools in astronomy.

One of his most significant theoretical advancements was the development of laws governing solar magnetic cycles. Building on earlier observations of sunspot cycles, Hale demonstrated that the Sun’s magnetic polarity reversed approximately every 11 years—a phenomenon now known as the Hale Cycle. This discovery helped explain long-standing mysteries about solar activity and its influence on Earth’s space environment, from auroras to disruptions in radio communications.

Beyond the Sun, Hale’s spectroscopic techniques were applied to stars and nebulae, allowing astronomers to determine their chemical compositions, temperatures, and motions. His insistence on high-precision instrumentation led to refinements in diffraction grating technology, further enhancing astronomers’ ability to dissect light from celestial sources.

Education and Mentorship

George Ellery Hale was not only a brilliant scientist but also a dedicated educator and mentor. He played a pivotal role in shaping modern astronomy by fostering the careers of younger researchers. Among his most notable protégés was Edwin Hubble, whose discoveries at Mount Wilson redefined humanity’s understanding of the cosmos. Hale’s encouragement of Hubble’s work with the 100-inch telescope led to the confirmation of galaxies beyond the Milky Way and the concept of an expanding universe—pillars of modern cosmology.

Hale also worked closely with researchers such as Walter Adams, who made critical contributions to stellar classification, and Harlow Shapley, who mapped the structure of our galaxy. His approach combined rigorous scientific standards with a collaborative spirit, ensuring that Mount Wilson and later Palomar were not just collections of instruments but thriving intellectual communities.

The California Institute of Technology and Astronomy’s Institutional Growth

Beyond observatories, Hale was instrumental in transforming Pasadena into a global center for astrophysics. His vision extended to education, and he played a central role in the development of the California Institute of Technology (Caltech). Originally known as Throop College, Hale saw in it the potential for a premier scientific institution. Through his leadership and fundraising efforts, Caltech became one of the most respected science and engineering schools in the world.

Hale’s influence ensured that astronomy and astrophysics were central to Caltech’s mission. He pushed for the establishment of strong ties between academic research and observatory work, creating a model that other institutions would later emulate. His legacy at Caltech can still be seen today in its partnerships with the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) and ongoing leadership in space exploration.

Struggles with Health and Personal Challenges

Despite his towering achievements, Hale’s life was not without hardship. He suffered from persistent health issues, including severe episodes of what was likely bipolar disorder, which he referred to as his "nervous exhaustion." These struggles forced him to take extended leaves from his work, yet even during periods of recuperation, he remained intellectually active, writing and planning future projects.

His condition sometimes made his leadership difficult, but his colleagues respected his resilience. In many ways, his personal battles humanized a man whose accomplishments might otherwise seem superhuman. Friends and fellow scientists noted his ability to remain visionary despite these challenges, often working through his ideas even when unable to participate directly in research.

Honors and Recognition

Hale’s work earned him numerous accolades throughout his lifetime. He received the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society, the Bruce Medal, and the Henry Draper Medal, among others. He was a member of the National Academy of Sciences and served as president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

Perhaps the most fitting tribute, however, is the number of astronomical institutions and objects named after him—from the Hale Telescope to the Hale-Bopp comet (co-discovered by Alan Hale, no relation). His influence is also seen in the naming of craters on the Moon and Mars in his honor, as well as the asteroid 1024 Hale. These tributes reflect not just his impact on science but also the enduring respect he commands in the scientific community.

(Second part of the article ends here. Awaiting your prompt to continue.)

Hale's Enduring Influence on Modern Astronomy

George Ellery Hale's revolutionary approach to astronomical research permanently altered the course of astrophysics. His insistence on ever-larger, more precise telescopes established a paradigm that continues to drive observatory construction today. Modern instruments like the Thirty Meter Telescope and the Extremely Large Telescope follow directly in Hale's tradition of pushing optical engineering to its limits. The foundational principle he established - that deeper cosmic understanding requires increasingly powerful observational tools - remains central to astronomical progress nearly a century later.

Hale's work fundamentally transformed astronomy from a largely observational discipline into an experimental physical science. By adapting laboratory techniques like spectroscopy for astronomical use, he bridged the gap between physics and astronomy, effectively creating modern astrophysics. Contemporary instruments like the Hubble Space Telescope and James Webb Space Telescope still employ spectroscopic methods refined by Hale, proving the enduring value of his innovations.

The Solar-Stellar Connection

Hale's pioneering solar research established the foundation for understanding stars throughout the universe. His discovery that sunspots were regions of intense magnetic activity proved transformative, revealing that similar processes occur across all stars. Today's heliophysicists continue to build on Hale's work, using spacecraft like NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory to study the Sun's magnetic field with precision he could only dream of.

The field of stellar magnetism that Hale initiated has expanded dramatically. Modern astronomers now routinely measure magnetic fields in distant stars, discovering phenomena like starspots hundreds of times larger than sunspots. Hale's early insights helped create our current understanding of stellar activity cycles, including how similar magnetic phenomena affect planets orbiting other stars.

Legacy in Astronomical Institutions

The institutional framework Hale established continues to shape astronomy today. The Mount Wilson Institute, which maintains his first great observatory, still supports astronomical research from the same telescopes Hale helped build. Palomar Observatory remains an active research facility, with the 200-inch Hale Telescope regularly contributing to discoveries despite its age.

Perhaps Hale's greatest institutional achievement was helping transform Caltech into a world-class research university. The astronomy program he founded there continues to lead in astrophysical research, maintaining the strong connection between academia and observatories that Hale so valued. This model has been replicated at universities worldwide, ensuring that theoretical and observational astronomy advance together.

Influence on Space-Based Astronomy

While Hale worked strictly with ground-based telescopes, his influence extends to space astronomy. The principles he established about instrument sensitivity and observing techniques directly informed the design of orbiting observatories. NASA's Great Observatories program, including the Hubble, Chandra, and Spitzer telescopes, reflects Hale's philosophy of building specialized instruments to study different wavelengths of light.

Modern solar observatories like SOHO and Parker Solar Probe continue the solar research Hale pioneered, employing advanced versions of his spectroscopic techniques to study our star. Discoveries about the solar wind, solar flares, and coronal mass ejections all trace their lineage back to Hale's foundational work in solar physics.

Public Engagement and Science Communication

Hale was ahead of his time in recognizing the importance of public engagement with science. He frequently wrote popular articles about astronomy and worked to make scientific discoveries accessible to general audiences. This tradition of public communication remains strong in astronomy today, with scientists regularly appearing in media and giving public talks about their research.

The many books and articles Hale produced helped inspire generations of astronomers. His ability to articulate both the romance and the rigorous science of astronomy set a standard for science writing that continues to influence how researchers communicate with the public today. Institutions like Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles, which Hale advised on, carry forward his vision of making astronomy accessible to all.

Technological Innovations Beyond Astronomy

The technologies Hale developed found applications far beyond astronomy. His work on optical glass production techniques contributed to advancements in lens manufacturing that benefited fields from microscopy to photography. The precision engineering required to build his telescopes advanced mechanical and optical engineering across multiple industries.

Modern adaptive optics systems, which compensate for atmospheric distortion in real-time, build directly on Hale's work developing telescope optics. These systems now have medical applications, including improved retinal imaging in ophthalmology. The CCD technology developed for astronomical imaging similarly migrated to medical and industrial imaging systems.

Unfulfilled Visions and Future Directions

In his later years, Hale envisioned even more ambitious projects that were beyond the technology of his time. He imagined networks of telescopes working together - a concept realized today in interferometer arrays like the Very Large Telescope Interferometer. His speculations about telescopes in space came to fruition with the launch of the Hubble Space Telescope and other orbital observatories.

The next generation of telescopes, including giant segmented-mirror instruments and space-based gravitational wave detectors, continue the tradition of bold instrumentation Hale pioneered. His spirit of ambitious scientific vision lives on in projects like the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) and next-generation solar observatories now in development.

Final Years and Lasting Impact

As his health declined, Hale remained intellectually active, publishing papers and advising colleagues until his death in 1938. His final writings speculated about new astronomical frontiers he wouldn't live to see explored, including the nature of interstellar matter and the possibility of detecting planets around other stars - both areas of intensive research today.

Hale's death was mourned by the global scientific community, but his influence only grew in the following decades. The institutions he built continued to produce groundbreaking research, and the telescopes he helped create kept making important discoveries years after his passing. The Hale Telescope at Palomar remained astronomy's premier research instrument until the 1980s, and still contributes valuable observations today.

Conclusion: A Revolutionary Visionary

George Ellery Hale stands as one of history's most important astronomers, not just for his individual discoveries but for fundamentally transforming how astronomy is practiced. His vision shaped the entire field of astrophysics, from instrumentation to theory to institutional organization. The telescopes he built opened cosmic frontiers, while his scientific insights revealed the fundamental physical processes governing stars.

Modern astronomy, with its massive international collaborations and billion-dollar instruments, might seem far removed from Hale's era. Yet his fingerprints remain visible in every major astronomical endeavor. As we continue to explore the universe with increasingly sophisticated tools, we are still following the path George Ellery Hale blazed - one of bold vision, technological innovation, and unrelenting curiosity about the cosmos.

Pierre-Simon Laplace: The French Newton Who Shaped Modern Science

Introduction to a Pioneering Mind

Pierre-Simon Laplace, a towering figure in French mathematics and astronomy, revolutionized our understanding of the universe. Born in 1749 in Normandy, Laplace's contributions spanned celestial mechanics, probability theory, and mathematical physics. His work laid the groundwork for modern scientific disciplines, earning him the nickname "the French Newton."

Early Life and Scientific Foundations

Laplace's journey began in Beaumont-en-Auge, where his early aptitude for mathematics set him apart. By 1773, he was elected to the Académie des Sciences, a testament to his rapid rise in the scientific community. His early work focused on probability theory, culminating in his 1774 paper, Mémoire sur la probabilité des causes, which introduced Bayesian reasoning.

Key Contributions to Mathematics

- Laplace’s Equation: A fundamental differential equation in mathematical physics.

- Laplace Transform: A tool essential for solving differential equations.

- Laplacian Operator: Critical in vector calculus and physics.

Celestial Mechanics: Unraveling the Solar System

Laplace's magnum opus, the five-volume Traité de mécanique céleste (1799–1825), systematized celestial mechanics. He proved the long-term stability of planetary motions, addressing a major challenge of Newtonian physics. His nebular hypothesis proposed that the solar system formed from a rotating cloud of gas, a theory that influenced later models of planetary formation.

The Nebular Hypothesis

Laplace's hypothesis suggested that the sun and planets originated from a rotating nebula. This idea, though refined over time, remains a cornerstone of modern cosmology. His work provided a framework for understanding the formation of planetary systems, a topic still explored today.

Probability Theory: A New Analytical Framework

In 1812, Laplace published Théorie analytique des probabilités, which transformed probability from ad-hoc methods into a rigorous analytical theory. His contributions to Bayesian inference and statistical reasoning are foundational in modern data analysis and machine learning.

Philosophical Impact: Determinism and Laplace’s Demon

Laplace is famously associated with scientific determinism, encapsulated in the thought experiment known as "Laplace’s demon." This idea posits that if an intelligence knew the precise location and momentum of every atom in the universe, it could predict the future with absolute certainty. While later developments in quantum mechanics and chaos theory have nuanced this view, Laplace's deterministic philosophy remains a pivotal concept in the history of science.

Legacy and Modern Relevance

Laplace's influence extends beyond his lifetime. His name is immortalized in mathematical objects such as the Laplacian and Laplace transform, which are integral to engineering, physics, and mathematics curricula worldwide. Recent scholarly work continues to reassess his contributions, highlighting his role as a synthesizer of mathematical and scientific ideas.

Educational and Digital Revival

In the 2020s, there has been a resurgence of interest in Laplace's work. Online biographies, course materials, and museum exhibits have revisited his original manuscripts, translating his probabilistic arguments into modern notation. This revival underscores the enduring relevance of his ideas in contemporary probability theory and celestial mechanics.

Conclusion: A Lasting Scientific Legacy

Pierre-Simon Laplace's contributions to mathematics, astronomy, and probability theory have left an indelible mark on science. His work not only advanced our understanding of the universe but also provided tools and frameworks that continue to shape modern scientific inquiry. As we delve deeper into his life and achievements in the subsequent parts of this article, we will explore the nuances of his scientific methods and the broader implications of his philosophical ideas.

Political Influence and Institutional Roles

Pierre-Simon Laplace was not only a scientific luminary but also a prominent figure in French political and academic circles. His career spanned the tumultuous periods of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic era, during which he held significant positions that allowed him to shape France's scientific landscape.

Key Political and Academic Positions

- Académie des Sciences: Elected in 1773, Laplace became a leading member of this prestigious institution, contributing to its influence and prestige.

- Minister of the Interior: Briefly served under Napoleon Bonaparte in 1799, demonstrating his versatility beyond the scientific realm.

- Senator and Chancellor: Appointed to the French Senate and later served as Chancellor of the Senate, further cementing his role in French governance.

Promotion of Scientific Institutions

Laplace played a crucial role in the establishment and promotion of scientific institutions in France. He was instrumental in the development of the metric system, which standardized measurements and facilitated scientific and commercial exchanges. His efforts in educational reform helped modernize French academia, ensuring that scientific advancements were integrated into the national curriculum.

Scientific Controversies and Collaborations

Throughout his career, Laplace engaged in numerous scientific debates and collaborations that shaped his theories and methodologies. His interactions with contemporaries such as Joseph-Louis Lagrange and Adrien-Marie Legendre were pivotal in advancing his work.

Collaborations with Leading Scientists

- Joseph-Louis Lagrange: Laplace and Lagrange collaborated on various aspects of celestial mechanics, with Laplace often building upon Lagrange's foundational work.

- Adrien-Marie Legendre: Their interactions in the field of mathematical analysis led to significant advancements in the understanding of differential equations.

- Antoine Lavoisier: Laplace worked with Lavoisier on early experiments in thermochemistry, contributing to the development of the calorimeter.

Scientific Debates and Criticisms

Laplace's theories were not without controversy. His nebular hypothesis faced skepticism from some contemporaries who favored alternative explanations for the formation of the solar system. Additionally, his deterministic views were later challenged by advancements in quantum mechanics and chaos theory, which introduced elements of unpredictability and randomness.

"What we know is very little, and what we do not know is immense." — Pierre-Simon Laplace

Laplace’s Impact on Modern Science and Technology

The legacy of Pierre-Simon Laplace extends far beyond his lifetime, influencing numerous fields in modern science and technology. His theoretical contributions have found practical applications in various disciplines, from engineering to artificial intelligence.

Applications in Engineering and Physics

- Laplace Transform: Widely used in electrical engineering for analyzing circuits and systems.

- Laplace’s Equation: Fundamental in fluid dynamics, electromagnetism, and heat transfer.

- Celestial Mechanics: His work on planetary motion remains crucial for space exploration and satellite technology.

Influence on Probability and Statistics

Laplace's contributions to probability theory have had a lasting impact on statistics and data science. His development of Bayesian inference is now a cornerstone of machine learning and artificial intelligence. Modern algorithms for predictive modeling and data analysis owe much to his pioneering work.

Educational Influence

Laplace's theories and methods are integral to modern educational curricula. His work is taught in mathematics, physics, and engineering programs worldwide. Textbooks on differential equations, probability, and celestial mechanics frequently reference his contributions, ensuring that new generations of scientists and engineers are familiar with his ideas.

Recent Scholarly Reassessments

In recent years, historians and scientists have revisited Laplace's work, offering new perspectives on his contributions and legacy. These reassessments highlight the evolving understanding of his role in the development of modern science.

Historiographical Trends

- Synthesizer of Ideas: Modern scholars emphasize Laplace's role as a synthesizer who unified methods across mathematics, astronomy, and probability.

- Beyond Determinism: Recent analyses explore how Laplace's deterministic views contrast with later developments in statistical mechanics and chaos theory.

- Collaborative Nature: New research highlights the collaborative aspects of Laplace's work, acknowledging the contributions of his contemporaries.

Digital and Pedagogical Revival

The digital age has brought renewed interest in Laplace's original manuscripts and theories. Online platforms and educational resources have made his work more accessible, allowing students and researchers to engage with his ideas in new ways. Translations of his probabilistic arguments into modern notation have facilitated a deeper understanding of his contributions to probability theory and celestial mechanics.

Public and Scientific Communication

Laplace's name continues to resonate in public science communication. His nebular hypothesis and the concept of Laplace’s demon are frequently cited in discussions about cosmology and predictability. Popular science articles and documentaries often reference his work to illustrate the evolution of scientific thought.

Conclusion: A Multifaceted Legacy

As we have explored in this second part of the article, Pierre-Simon Laplace was not only a brilliant scientist but also a influential figure in French politics and academia. His collaborations and controversies shaped his theories, while his impact on modern science and technology continues to be felt today. Recent scholarly reassessments have provided new insights into his work, ensuring that his legacy remains relevant in the digital age.

In the final part of this article, we will delve into Laplace's personal life, his philosophical views, and the enduring influence of his ideas on contemporary scientific thought. We will also explore how his work is being preserved and promoted in the 21st century, ensuring that future generations continue to benefit from his groundbreaking contributions.

Personal Life and Philosophical Views

Pierre-Simon Laplace led a life marked by both scientific brilliance and personal resilience. Born into a modest family in Normandy, his rise to prominence was fueled by his relentless pursuit of knowledge and his ability to navigate the complex political landscape of his time.

Early Life and Education

Laplace's early education was shaped by his local school in Beaumont-en-Auge, where his exceptional mathematical abilities were first recognized. His journey to Paris at the age of 18 marked the beginning of his illustrious career. There, he quickly gained the attention of prominent mathematicians, securing a position at the École Militaire, where he taught mathematics to young officers.

Family and Personal Relationships

Despite his demanding scientific and political commitments, Laplace maintained a close-knit family life. He married Marie-Charlotte de Courty de Romanges in 1788, and the couple had two children. His personal correspondence reveals a man deeply devoted to his family, providing a stark contrast to his public persona as a rigorous and sometimes austere scientist.

Philosophical Views and Scientific Determinism

Laplace is perhaps best known for his philosophical stance on scientific determinism. His famous thought experiment, "Laplace’s demon," posits that if an intelligence knew the precise location and momentum of every atom in the universe, it could predict the future with absolute certainty. This idea, though later challenged by quantum mechanics and chaos theory, remains a cornerstone in discussions about predictability and free will.

"We may regard the present state of the universe as the effect of its past and the cause of its future." — Pierre-Simon Laplace

Preservation and Promotion of Laplace’s Legacy

The preservation of Laplace’s legacy is a testament to his enduring influence on science and education. Various initiatives and institutions continue to promote his work, ensuring that his contributions remain accessible and relevant.

Museums and Archives

- Musée des Arts et Métiers: Located in Paris, this museum houses many of Laplace’s original manuscripts and instruments, offering visitors a glimpse into his scientific process.

- Bibliothèque Nationale de France: Holds a vast collection of Laplace’s published works and personal correspondence, providing valuable resources for researchers.

- Online Archives: Digital platforms such as Gallica and Google Books have digitized many of Laplace’s texts, making them accessible to a global audience.

Educational Programs and Initiatives

Educational institutions worldwide continue to teach Laplace’s theories as part of their mathematics, physics, and engineering curricula. Initiatives such as:

- MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses): Platforms like Coursera and edX offer courses that delve into Laplace’s contributions to probability theory and celestial mechanics.

- University Lectures: Prestigious universities, including the Sorbonne and MIT, feature lectures and seminars dedicated to exploring Laplace’s impact on modern science.

- Science Outreach Programs: Organizations like the French Academy of Sciences conduct workshops and public lectures to engage younger audiences with Laplace’s ideas.

Commemorative Events and Publications

To honor Laplace’s contributions, various events and publications are regularly organized:

- Annual Conferences: Scientific conferences often include sessions dedicated to Laplace’s work, particularly in the fields of mathematical physics and astronomy.

- Special Editions and Books: Publishers release annotated editions of Laplace’s major works, as well as biographies that contextualize his life and achievements for modern readers.

- Exhibitions: Museums and scientific institutions host exhibitions showcasing Laplace’s manuscripts, instruments, and personal artifacts, drawing attention to his multifaceted legacy.

Laplace’s Influence on Contemporary Scientific Thought

The ideas and methodologies developed by Pierre-Simon Laplace continue to shape contemporary scientific thought. His work has found applications in diverse fields, from artificial intelligence to quantum physics.

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

Laplace’s contributions to probability theory and Bayesian inference are fundamental to modern machine learning algorithms. Techniques such as Bayesian networks and Markov chain Monte Carlo methods rely on principles that Laplace helped establish. These methods are crucial for:

- Predictive Modeling: Used in fields like finance, healthcare, and weather forecasting.

- Natural Language Processing: Powers applications such as chatbots and language translation services.

- Computer Vision: Enables advancements in image recognition and autonomous vehicles.

Quantum Physics and Chaos Theory

While Laplace’s deterministic views have been challenged by quantum mechanics, his work remains a critical reference point. The contrast between Laplace’s determinism and the probabilistic nature of quantum physics highlights the evolution of scientific thought. Additionally, chaos theory—which explores the unpredictability of complex systems—offers a nuanced perspective on Laplace’s ideas, showing how small variations can lead to vastly different outcomes.

Space Exploration and Astronomy

Laplace’s theories on celestial mechanics continue to inform modern astronomy and space exploration. His work on the stability of planetary orbits is essential for:

- Satellite Technology: Ensuring the precise positioning and longevity of satellites in orbit.

- Interplanetary Missions: Calculating trajectories for spacecraft exploring our solar system and beyond.

- Exoplanet Research: Understanding the formation and behavior of planetary systems around other stars.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of Pierre-Simon Laplace

Pierre-Simon Laplace stands as one of the most influential scientists in history, with a legacy that spans mathematics, astronomy, physics, and probability theory. His groundbreaking work laid the foundations for numerous scientific disciplines and continues to inspire researchers and educators worldwide.

Key Takeaways

- Foundational Contributions: Laplace’s development of the Laplace transform, Laplace’s equation, and the nebular hypothesis revolutionized multiple fields.

- Probability and Statistics: His systematic approach to probability theory and Bayesian inference remains vital in modern data science and machine learning.

- Scientific Determinism: The concept of Laplace’s demon continues to provoke discussions on predictability and free will.

- Educational Impact: Laplace’s theories are integral to contemporary STEM education, ensuring his ideas are passed down to future generations.

- Modern Applications: From artificial intelligence to space exploration, Laplace’s work underpins technologies that shape our world today.

As we reflect on Laplace’s extraordinary life and achievements, it is clear that his influence extends far beyond his time. His ability to synthesize complex ideas and his relentless pursuit of knowledge have left an indelible mark on science. In an era where technology and discovery advance at an unprecedented pace, the principles and methodologies developed by Laplace remain as relevant as ever. His legacy serves as a reminder of the power of curiosity and the enduring impact of scientific inquiry.

In celebrating Pierre-Simon Laplace, we honor not just a scientist, but a visionary whose ideas continue to illuminate the path of human understanding. As future generations build upon his work, Laplace’s contributions will undoubtedly remain a cornerstone of scientific progress, inspiring innovation and discovery for centuries to come.

Meton of Athens: The Astronomer Who Shaped Ancient Greek Science

Introduction to Meton of Athens

Meton of Athens, a figure who lived during the 5th century BC, is often remembered not only for his contributions to astronomy but also for his pivotal role in the development of the calendar. As an ancient Greek astronomer, Meton's work laid foundational stones that would inform scientific and cultural perspectives for centuries. His achievements underscore the vital link between celestial observations and human life, reflecting the rich intellectual tradition of ancient Greece. Although few details about his personal life survive, Meton's work has solidified his place among the great thinkers of the classical world.

The Context of Meton's Work

During Meton's lifetime, Athens was a bustling hub of innovation and intellectual exploration. Known as the golden age of Pericles, this era witnessed monumental achievements in philosophy, drama, politics, and science. Meton was an active participant in this vibrant intellectual community. The advancement of astronomy was particularly critical, as it was intertwined with the religious festivals, agriculture, and navigation upon which Athenian society depended.

In this context, Meton's interest in celestial phenomena was far more than a mere academic pursuit. The need for accurate calendars to guide agricultural and religious activities placed high importance on understanding lunar and solar cycles. Observing the heavens was a gateway to aligning human activities with the cosmic order, and Meton's work aimed to bring precision to these cosmic observations.

The Metonic Cycle: A Pioneering Discovery

Meton's most notable contribution to science is the Metonic cycle. This cycle, which spans 19 years, demonstrates how nearly every 19 years, the lunar month aligns with the solar year. This understanding was crucial for devising a more accurate calendar. By observing that 235 lunar months very closely equaled 19 solar years, Meton provided a practical framework that enabled the synchronization of lunar and solar calendars, which then were often at odds.

The implications of the Metonic cycle were monumental. It allowed for more precise planning of agricultural activities by predicting the phases of the moon. This understanding was also crucial for setting religious festivals, many of which depended on the lunar calendar. The cycle's precise calculations demonstrated a profound understanding of the complex celestial mechanics at play, evidencing the rigorous methodologies employed by Meton and his contemporaries.

Beyond Astronomy: Meton's Diverse Interests

While Meton's legacy is predominantly tied to his astronomical work, historical records suggest his interests were diverse. Ancient sources often reference his engagement with mathematics and its applications in architectural design. He was reportedly involved in the construction of the Tholos, a rotunda within the Athenian Agora. This further reflects his deep understanding of geometry and engineering, disciplines that were inseparable from astronomical research in ancient Greece.

Meton's work also influenced political life in Athens, where the integration of these sciences into civic infrastructure granted him considerable influence. By aligning architectural ventures with astronomical phenomena, he contributed to the societal fabric of Athens, ensuring his innovations were cemented into the daily and civic life of its citizens.

A Lasting Legacy in Science

Meton's influence extends beyond his contemporaries, impacting subsequent generations of astronomers and mathematicians. His work, though primarily focused on harmonizing the lunar and solar calendars, laid the groundwork for future scientific inquiry. The Metonic cycle was later adopted and refined by other cultures, including the Babylonians and the Hebrews, highlighting its mathematical robustness and broad applicability.

Furthermore, Meton's pioneering findings would go on to influence astronomical systems of the Hellenistic period. Notably, his work provided a foundation upon which later astronomers like Hipparchus and Ptolemy would build. These figures expanded upon Meton's cycles, integrating more complex mathematical models and observations to develop an even deeper understanding of celestial dynamics.

Meton of Athens exemplifies the profound interrelatedness of diverse scientific disciplines in ancient Greece. His lifetime's work underscored the importance of synchronized calendars, proving indispensable not only to Athenians but to cultures worldwide. As modern technology continues to depend on astronomical cycles, Meton's insights remain relevant, reminding us of the enduring legacy of ancient innovators.

The Impact of the Metonic Cycle on Ancient Calendars

Meton's groundbreaking discovery of the Metonic cycle had an enormous impact on the refinement and creation of calendars in the ancient world. His cycle, relying on the alignment of lunar months with solar years over a 19-year span, became fundamental in correcting inaccuracies in earlier calendar systems. At a time when societies were evolving from seasons-based calendars to ones influenced by astronomy, Meton's work bridged the gap between empirical observation and practical application.

The Athenians, known for their dedication to aligning public life with cosmic phenomena, integrated the Metonic cycle into their civil calendar. Every 19 years, adjustments were made to coincide lunar months with the solar year, incorporating "intercalary months" to keep these calendars synchronized. This approach showed innovative thinking, allowing the Athenian polis to maintain their schedules for agricultural, administrative, and religious events. Such synchronization helped them avoid the pitfalls of earlier systems that grew out of sync with the seasons, leading to confusion and inefficiency.

This Hellenic innovation spread, influencing neighboring civilizations and regions within the Greek world. The Metonic cycle moved beyond Athens' borders as astronomers and mathematicians sought its stabilization for local calendars. Meton became a figure of study and admiration in academics of the time, and his work offered a blueprint for achieving balance within the broader cosmic order.

Adaptation of the Metonic Cycle in Other Cultures

As knowledge exchanged hands in the ancient world, the principles of the Metonic cycle resonated with a variety of cultures seeking celestial guidance. The Babylonians, who had an extensive tradition of astronomical records and observations, found the cycle beneficial for their advanced calendrical revisions. By incorporating Meton’s findings, they further honed their methods of predicting lunar phases and years, leading to a more consistent system over time. This cross-cultural acknowledgment represented a union of empirical study and the diversification of astronomical techniques.

In parallel, the Hebrew calendar also integrated the principles of the Metonic cycle. Specifically, the Jewish priests adopted the cycle to determine religious observances, like Passover. This unification of calendar systems provided a mechanism to coordinate lunar synodic months with solar realities, ensuring that religious activities were seasonally appropriate. Such integration underscored the importance of precise celestial understanding in maintaining societal cohesion and honoring sacred traditions.

These adaptations of Meton's cycle illustrate an ancient network of scientific communication and innovation, where cultural and intellectual borrowing led to refined methodologies and shared advancements. The spread of Meton’s cycle across different civilizations is a testament to the ingenuity and universality of his work, further deepening its historical significance.

Challenges and Limitations of Meton's Work

Despite its groundbreaking nature, the Metonic cycle was not without its critics or limitations. Some evidence suggests that subsequent astronomers, while largely building upon Meton's framework, sought to address discrepancies that arose from his intricate calculations. The cycle, based on empirical observations, was not perfectly accurate; solar years and lunar months do not precisely overlay, necessitating small adjustments to calendar systems even when using the Metonic cycle. These tiny misalignments called for continuous refinement and fine-tuning to enhance synchronization over long periods.

Moreover, changes in global perspective occasionally led to the questioning of Meton's work. As Greek influence waned and Roman authority rose, some aspects of Greek astronomical efforts were overlooked or even disregarded altogether. This is not to say that Meton's work was dismissed but rather that it found itself sharing space with competing and emerging astronomical theories of the day.