Valens: The Emperor Who Shaped Byzantine History

The Rise to Power

In the annals of Byzantine history, the reign of Valens, who ruled from 364 to 378 AD, is significant for its complexity and impact. Born around 328–330 in Cynegila, Thrace, Valens emerged from humble origins to ascend to the throne amid a tumultuous period. His rapid rise to power is a testament to the fluid nature of political maneuvering in late Roman and early Byzantine politics.

Valens was the elder brother of Emperor Valentinian I and came into the spotlight when his older brother inherited the purple in 364 AD. Upon Valentinian’s death in 375 AD, power shifted to Valens, who then assumed full control of the Roman Empire. This transition was not without controversy; rumors circulated about a plot orchestrated by his wife Justina to usurp the throne. However, the Senate and other high-ranking officials supported Valens, thus legitimizing his rule.

Valens’ accession led to the partition of the empire under the Peace of Merida. According to this agreement, Valentinian retained control over the western provinces while Valens governed the eastern territories, which included Greece, Asia Minor, Syria, and Egypt. Despite this arrangement, tensions simmered beneath the surface as each emperor vied for dominance and tried to consolidate their regions’ resources and influence.

The Early Reign and Military Campaigns

Valens’ early reign was marked by a series of military campaigns designed to solidify his power and secure the empire’s borders, particularly against threats from the east. One such campaign was launched against the Sasanian Empire in Persia. Although initially successful, these expeditions were met with challenges that tested Valens’ strategic acumen and his ability to maintain the loyalty of his troops.

In 370 AD, Valens marched his armies into Syria to confront the Sassanid forces. While he achieved some victories, the expedition culminated in the battle of Singara in 370 AD, where Valens faced significant setbacks. His tactical errors and the stubborn resistance of the Persian army left him reeling from a series of defeats. Historians often attribute these failures to Valens' lack of firsthand experience with frontline combat, which was more typical of many generals of his time.

The defeat at Singara did not deter Valens from engaging in further military excursions. In 372 AD, he led yet another expedition aimed at capturing Nisibis, a strategically important city located between the Roman and Sassanid territories. This ambitious move, however, resulted in another crushing defeat. The Sassanids under their leader Hormizd I launched a fierce counterattack, inflicting heavy losses on the Roman forces. These repeated failures cast doubt on Valens’ leadership abilities and raised questions about his suitability as an emperor capable of defending the Eastern Front.

Despite these setbacks, Valens continued his efforts to assert dominance over his territories. One of his key initiatives involved restructuring the administration of the Eastern provinces. He appointed loyal supporters and reshaped the bureaucratic apparatus to enhance his control. This reorganization included the appointment of Eutropius, who served as praetorian prefect and wielded considerable influence. These internal reforms aimed to strengthen Valens' hold on the empire and ensure a smooth transition of power within his administration.

Nevertheless, even with these attempts at stabilization, regional conflicts persisted. Civil strife within the empire, exacerbated by external pressures, created an unstable environment. Among these conflicts was the issue of religious persecution, primarily directed against the Arian Christians. Valens’ policies toward religious minorities often reflected his conservative stance and his reliance on traditional Roman values. These policies contributed to widespread discontent among various social groups and further undermined his authority.

It is during this early reign that Valens also found himself engaged in domestic issues, including political alliances and the distribution of resources. His approach to governance often oscillated between asserting authoritarian control and seeking support through more traditional means like patronage. These fluctuations highlighted both his strengths and weaknesses as a leader.

Conclusion

Valens' early years as emperor were characterized by a combination of military endeavors, internal reforms, and complex personal and political dynamics. His reign laid the groundwork for future developments within the empire and showcased the challenges inherent in maintaining stability across vast territories fraught with internal and external threats. As we delve deeper into his legacy, it becomes clear that Valens’ approach to leadership was multifaceted and shaped by both opportunity and necessity.

The Battle of Adrianople and Its Aftermath

The turning point of Valens' reign came abruptly with the Battle of Adrianople in 378 AD. This decisive battle, fought against the Goths, marked a significant turning point in Valens' career and the course of history. Located near Adrianople (modern-day Edirne, Turkey), this battle revealed the vulnerabilities of the Roman military apparatus and underscored the growing existential threat posed by barbarian invasions.

On August 9, 378 AD, Valens led his Roman forces into battle against the Gothic leader Fritigern and his army of Goths. The Goths, facing a harsh winter and unable to sustain themselves, had sought refuge within the Roman Empire. Despite initial agreements allowing them safe passage through Roman territory, tensions escalated when Valens decided to attack them before they could leave. This decision reflected Valens' belief that the Goths posed an imminent threat to the empire's security—a judgment that proved costly both strategically and politically.

Valens' forces were comprised largely of the elite field army and heavy cavalry. However, these forces suffered severely due to poor planning and lack of preparedness. The Roman soldiers, accustomed to defensive tactics and less experienced in dealing with mobile enemies, found themselves outmatched by the agile and resourceful Goths. The ensuing battle was brutal and chaotic. Despite outnumbering the Goths, the Roman legions were overwhelmed by the sheer ferocity and adaptability of their enemies.

Valens, commanding from the front lines, was killed in the fighting—an incident that shocked the remnants of his army and plunged them into panic. With their leader gone, the Roman troops fragmented, unable to mount a coordinated defense. The loss at Adrianople was catastrophic; it resulted in an estimated three-quarters of Valens' army being wiped out, along with significant Roman casualties. This defeat not only marked a tragic end to Valens' rule but also heralded a new era of Goth power within the empire.

The aftermath of the battle was equally dramatic. The surviving Roman soldiers, bereft of leadership and morale, retreated back to Constantinople in disarray, leaving behind a vacuum of authority in the eastern provinces. Gothic leaders seized the opportunity to extend their influence further into Roman territory. Fritigern, recognizing the weakness of the remaining Roman defenses, sought to exploit this situation for his own gain. He moved swiftly to gain control over strategic locations, effectively establishing the Goths as a dominant force within the empire.

Valens' death and the subsequent chaos led to a period of intense political maneuvering. His widow Thermantia took steps to secure the throne for her sons, but the Senate and other powerful factions sought to place someone else on the throne. This struggle for power, coupled with the increasing unrest among the populace, set the stage for further instability within the empire.

The battle at Adrianople not only ended Valens' personal reign but also had long-lasting consequences for the Roman Empire. It signaled a significant shift in the balance of power between the empire and its barbarian neighbors. This shift would have profound implications for the subsequent emperors and the overall trajectory of Byzantine history.

Reforms and Legacy

In the wake of the disaster at Adrianople, Valens' immediate successors were forced to address the structural weaknesses of the empire. Following his death, his son Valentinian II, supported by Theodosius I, became co-emperor, leading to a brief period of co-rule. The two emperors worked together to stabilize the empire, but the scars left by Adrianople were deep and enduring.

Valens had been a proponent of religious orthodoxy, and his policies towards religious minorities contributed to political divisions within the empire. His support for Arian Christianity alienated Nicene Christians and other factions, leading to increased social tension. Despite his attempts to enforce religious conformity, his legacy of religious polarization lasted well into the late antique period.

Valens' reforms were predominantly internal and aimed at shoring up the empire's administrative and military structures. He endeavored to centralize power and consolidate regional governance. However, these efforts were undermined by external pressures and internal dissent. His appointment of Eutropius as praetorian prefect, a position of great influence, demonstrates his commitment to securing loyal administrators who could help navigate the empire's challenges.

Despite these initiatives, the core weaknesses of the empire remained unresolved. The military campaigns against the Sassanids and the ongoing Barbarian incursions highlighted the broader problems of Roman defenses and strategy. The inability to secure the frontiers and provide adequate resources to the military further weakened the empire's resilience.

One of Valens' lasting legacies is his role as a transitional figure in Byzantine history. While he failed to achieve the goals he set for himself, his reign serves as a critical backdrop for understanding the evolution of the Roman and later Byzantine Empires. His defeat and death at Adrianople marked a turning point where the rigid and often oppressive nature of Roman rule began to give way to a more complex and multicultural society. This shift would influence future generations of emperors and ultimately contribute to the cultural and institutional development of the Byzantine state.

Valens' reign, though brief and marred by military setbacks, remains a significant chapter in the history of the late Roman and early Byzantine periods. His story is one of ambition, miscalculation, and the harsh realities of governing a vast and diverse empire.

The Fall of Valens and Its Impact

The aftermath of Valens' death saw a brief period of co-rulership, primarily between Valentinian II and Theodosius I. Theodosius, a more capable and experienced military leader, gradually assumed greater control and eventually became sole ruler in 379 AD. Valentinian II, despite being young and naive, was placed on the throne under Theodosius' guardianship. This transfer of power marked the beginning of a new era in Byzantine history.

Theodosius' ascension brought with it a renewed sense of stability and purpose. Recognizing the profound impact of Adrianople, Theodosius embarked on extensive reforms aimed at revitalizing the empire. One of his most significant initiatives was the restructuring of the military. Drawing upon the lessons learned from Adrianople, Theodosius sought to modernize the Roman army, focusing on increased mobility and a more balanced approach to defense and offense.

To achieve this, Theodosius reorganized the field armies and improved logistical support systems. He introduced new tactical doctrines, emphasizing flexibility and rapid response capabilities. These changes enhanced the military's effectiveness and helped mitigate the immediate risks of barbarian invasions. Theodosius also recognized the importance of fortified positions and invested heavily in fortification projects along the Danube and other critical borders. These measures bolstered the empire's defensive capabilities and provided a foundation for long-term stability.

Religious unity and tolerance became central themes in Theodosius' reign. Building on Valens' policies but refining them, Theodosius promoted Nicene Christianity as the official state religion while granting toleration to other Christian sects. This shift in religious policy, outlined in the edicts of Milan in 313 AD and further enforced by Theodosius, helped reduce internal divisions and fostered a sense of collective identity among the diverse populations of the empire.

In addition to religious reforms, Theodosius implemented significant economic and administrative changes. He restructured the tax system to ensure fairer distribution of resources and reduced the burdens on the peasantry. By improving fiscal management and economic policies, Theodosius laid the groundwork for increased prosperity and economic stability. Furthermore, he strengthened provincial administration and encouraged local governance, which helped in fostering a sense of local autonomy and reducing dependence on centralized control.

However, the early years of Theodosius' reign were far from serene. Barbarian incursions continued, and the empire faced persistent threats from both the West and the East. Despite these challenges, Theodosius' leadership proved instrumental in navigating the turbulent waters of empire-building. His decisiveness and vision ensured that the empire did not collapse in the wake of Adrianople but instead emerged stronger and better organized.

Valens' reign, although brief and marked by significant failures, did not go unrecognized. His military expeditions, particularly those in the East, left a lasting impact on Byzantine military strategy and tactics. The disastrous outcome of Adrianople also highlighted the need for fundamental reforms in military organization and defense strategies, setting the stage for Theodosius' more comprehensive and effective policies.

The personal qualities of Valens have often been debated. Despite his tactical inadequacies, his commitment to the empire and his efforts to secure its borders should not be entirely dismissed. His willingness to undertake aggressive military campaigns, albeit with limited success, indicated a level of ambition and desire to protect the empire's interests. However, his lack of field experience and reliance on poorly understood terrain proved fatal.

Overall, Valens' reign stands as a pivotal moment in Byzantine history. It marked a turning point where the traditional Roman imperial system began to give way to more adaptive and strategic approaches. His defeat at Adrianople and subsequent death sent shockwaves through the empire, prompting a reevaluation of military and political policies. While his legacy included notable failures, his reforms and initiatives provided a foundation upon which future emperors like Theodosius could build a more resilient and effective empire.

In conclusion, Valens' reign, though characterized by significant challenges and failures, is a critical chapter in Byzantine history. His military blunders and tragic death at Adrianople not only ended his rule but also precipitated sweeping reforms that would shape the empire's trajectory for centuries to come. His story serves as a reminder of the complexities involved in maintaining vast and diverse empires and the enduring impact of individual leaders on historical narratives.

Tacitus: The Roman Historian and His Influence

The Life and Times of Tacitus

Early life and education played a crucial role in shaping Tacitus as a historian. He was born into a senatorial family, ensuring both financial stability and social mobility. His father, Marcus Claudius Fronto, was a lawyer and rhetorician who tutored several important figures, including Marcus Aurelius, suggesting a lineage rich with intellectual pursuits.

Although Tacitus’s formal education details remain uncertain, it is believed that he studied rhetoric, philosophy, and law at Eton College. His training in these subjects likely honed his abilities as a writer, orator, and analyst—a combination of skills that would later define his historical and political works. Tacitus's early experiences in literature and oratory would lay the groundwork for his detailed and eloquent historical narratives.

The political climate during his formative years was marked by a series of civil wars and political instability. This environment had a profound impact on young Tacitus, shaping his worldview and understanding of power. Tacitus would reflect upon these events throughout his career, often critiquing the excesses of the Flavian emperors and their successors, Nero and Domitian.

Political Career and Connections

By the mid-1st century AD, Tacitus held various public offices, including quaestor, tribune, and praetor. His political career allowed him extensive opportunities to observe Roman governance firsthand and provide firsthand accounts of major events. As an elected official, Tacitus participated actively in debates and held judicial functions, which further refined his critical perspective and analytical skills.

One of Tacitus's notable roles was holding office under Emperor Vespasian and his son Titus. During this period, Tacitus engaged in diplomatic missions and witnessed firsthand the aftermath of the Neronian purges. These experiences laid the foundation for his later critique of imperial tyranny and abuse of power. Tacitus's tenure under Emperor Trajan also provided additional insight into Roman administration and policy-making processes.

While serving in the Senate, Tacitus formed connections with influential figures such as Pliny the Younger and Emperor Trajan. These relationships were instrumental in establishing his reputation among the educated elite of Rome. Tacitus's writings and contributions to Roman historiography were recognized and valued by contemporaries like Pliny, who praised Tacitus’s work in correspondence.

Despite his prominent political career, Tacitus’s decision to write rather than maintain high political office indicates his preference for preserving historical records over active participation in the political arena. His choice to focus on literature and history was a strategic move, allowing him to preserve his voice during politically volatile times when direct involvement might have been dangerous or detrimental to his career.

The Historical Writings of Tacitus

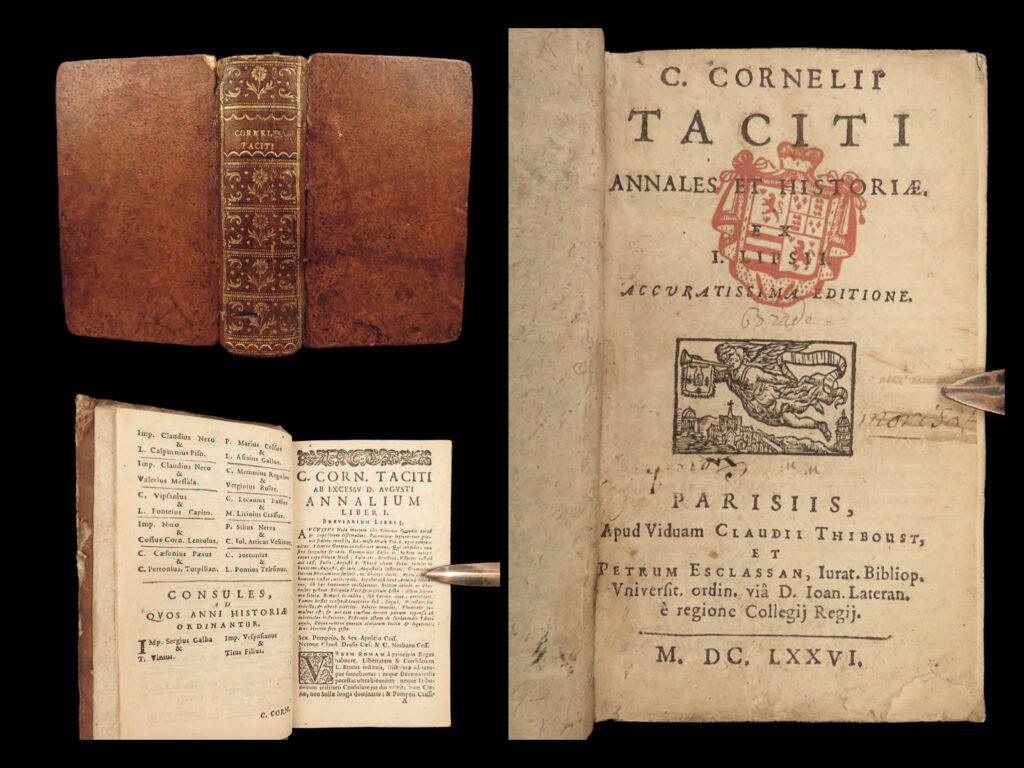

Tacitus left behind a prolific body of work that has made him one of the most read and studied historians from antiquity. His most famous works include the Histories, the Annals, and the Speeches (Dialogorum). Together, these texts provide a comprehensive yet often critical view of Roman history, particularly during the 1st century AD.

The Histories (Histoirs): Composed between c.83-89 AD, this manuscript recounts the events of the Roman Civil Wars from 69 AD onward. Tacitus covers the tumultuous period known as the Year of the Four Emperors, leading up to the fall of Nero and the accession of Vespasian. His narrative reflects the chaotic nature of the Flavian Dynasty and emphasizes the moral decay of Roman leadership during this crisis.

The Histories begins with the suicide of Nero and transitions into a detailed account of the struggles between Vespasian and his rivals. Tacitus criticizes Vespasian’s actions and highlights the brutal treatment of defeated rebels. His writing style is characterized by vivid descriptions and a keen eye for detail, providing readers with a nuanced understanding of the complex political landscape.

Tacitus's depiction of characters such as Vettius Batllus and Cernius Martialis reveals his deep engagement with the personalities and politics of his era. Through these historical portraits, he conveys the human face of power and the personal consequences of political intrigue. His narrative is not merely a straightforward recounting of events but a careful examination of why those events unfolded as they did.

The Annals (Annales): This massive work spans the history of Rome from the death of Augustus until the reign of Tiberius. Tacitus's Annals cover the reigns of the Julio-Claudian emperors, detailing their personal lives, their policies, and the societal changes brought about by their rule. One of the most famous sections deals with the assassination of Caligula and the subsequent power struggles among Claudius, Agrippina, and others, culminating in Nero’s rise to power.

In the Annals, Tacitus focuses less on grand political maneuvers and more on the personal motivations that drive Roman leaders and aristocrats. He exposes the corruption and decadence within the ruling classes, painting a picture of a civilization spiraling out of control due to moral decay and political greed. The Annals reveal Tacitus’s belief that the decline of the Roman Republic was hastened by the corruption and moral failings of its leaders.

Throughout these works, Tacitus employs a distinctive writing style known as "historical irony." This technique involves presenting events through a lens of critical commentary that often undermines contemporary understandings and interpretations. By juxtaposing factual reporting with sharp criticism, Tacitus invites readers to question their own assumptions and consider the broader implications of the historical events he describes.

The Dialogorum and Letters (Epistulae): Tacitus wrote a dialogue called Dialogorum, composed between 97-117 AD, discussing the nature of history and the craft of writing. This dialogue features conversations between prominent figures such as Julius Agricola and Julius Frontinus, providing insight into Tacitus’s views on historical methodology and the importance of accurate representation. Tacitus also produced letters (Epistulae) to friends and colleagues, offering personal reflections and critiques that complement his more formal historical writings.

In these epistles and dialogues, Tacitus explores themes such as moral philosophy, political theory, and the role of literature in society. He discusses the responsibilities of the historian and the need to separate fact from fiction. These works demonstrate Tacitus’s broader interests in moral philosophy and his commitment to ethical considerations in historical writing.

Through his diverse literary output, Tacitus established himself as a master of historical narrative and critique. His ability to combine rigorous research with compelling storytelling has ensured his enduring influence on Western historiography. By examining the complexities of Roman life and politics, Tacitus laid the foundation for a new genre of historical writing that continues to be studied and valued today.

Legacy and Impact on Later Historians

Tacitus's impact on later historians cannot be overstated. His influence extends beyond the realm of ancient history, shaping the way modern scholars perceive and interpret the past. One of Tacitus’s most significant contributions lies in his emphasis on historical criticism and the use of primary sources. His methods of scrutinizing evidence and questioning motives set a standard for future generations of historians.

One of the key aspects of Tacitus's legacy is the development of the critical approach to history. Rather than simply recounting events, Tacitus sought to analyze the underlying causes and motivations of political actions. His skepticism towards the motives of rulers and elites became a cornerstone of critical historiography. Tacitus was among the first to employ historical irony, using it to expose contradictions and moral failures.

Notable figures such as Edward Gibbon and Voltaire drew inspiration from Tacitus's methodological rigor. Gibbon, in particular, admired Tacitus's style and approached the writing of The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire with a similar critical eye. Tacitus’s emphasis on the moral dimension of historical events resonated with Gibbon, who sought to explain the decline of the Roman Empire through a combination of political and cultural factors.

Tacitus’s style has also influenced modern writers and journalists. His concise and powerful prose, combined with a deep psychological analysis, serves as a model for vivid and evocative historical writing. Writers like Friedrich Nietzsche, whose works often draw on Tacitus’s insights into political psychology and moral decay, have acknowledged Tacitus's influence on their own philosophies.

Furthermore, Tacitus’s work has been pivotal in shaping the field of classical studies. Scholars rely on his annals and histories to understand the political and social dynamics of ancient Rome. His detailed descriptions of events provide valuable context for interpreting other sources. Tacitus’s understanding of the importance of context and background information has become a fundamental aspect of modern historical research.

The influence of Tacitus extends beyond academia and into popular culture. Biopics and documentaries often draw heavily from his writings to bring Roman history to life. His descriptions of pivotal moments, such as the Nero fiddle scandal and the rise of Vespasian, are widely referenced in historical dramas and films. The intricate plots and characters in his works have inspired countless writers and filmmakers to explore the depths of human nature through the lens of ancient Rome.

Controversies and Critiques

Tacitus’s works are not without controversy. Some critics argue that his bias and selective reporting could lead to an incomplete or distorted view of Roman history. His negative portrayals of emperors and the nobility have been subject to scrutiny, with some scholars questioning whether his criticisms always align with historical facts.

For instance, Tacitus's depiction of Nero as cruel and tyrannical has been challenged by some historians who argue that Nero’s legacy has been exaggerated. While acknowledging Tacitus’s rhetorical skills, these critics point out that his narratives may contain elements of dramatic flair rather than objective truth. Similarly, Tacitus’s portrayal of the Flavian emperors as brutal and oppressive has been reinterpreted by some modern scholars who suggest that these rulers, despite their flaws, brought much-needed stability to a troubled empire.

Contemporary analyses often seek to balance Tacitus’s accounts with other historical sources. Critical editions, such as the works edited by Ronald Syme and John Jackson, provide annotations and introductions that help readers navigate the biases inherent in Tacitus’s writings. These editions highlight discrepancies and offer alternative interpretations, fostering a more nuanced understanding of Tacitus's text.

Nevertheless, Tacitus's influence endures because his works continue to provoke discussion and debate. His ability to present a multifaceted and layered version of the Roman past challenges simplistic narratives and encourages deeper inquiry into historical complexity. The controversy surrounding his writings underscores the enduring relevance of his critical and analytical approach.

A significant debate revolves around Tacitus’s treatment of ethnic groups, particularly the Jews and Slavs. His descriptions, often tinged with xenophobia, raise ethical concerns and challenge modern sensibilities. Some critics argue that Tacitus's portrayal of these groups perpetuates problematic stereotypes, while others acknowledge the historical context within which he wrote.

Modern scholars often view Tacitus’s works as products of their time, reflecting the social and political norms of the late Roman Empire. Recognizing these biases helps contemporary readers appreciate the depth of Tacitus’s analysis while critically evaluating his content. By engaging with Tacitus through a lens of historical and cultural awareness, scholars can better understand both the power and limitations of his historical narratives.

Impact on Cultural Perception

Tacitus’s influence has extended far beyond the academic realm, permeating popular culture and shaping public perception of ancient Rome. His portrayal of the Roman Empire, with its opulent splendor and moral bankruptcy, has become deeply ingrained in Western thought. Films, novels, and television series frequently draw from Tacitus's vivid descriptions to depict the Roman world.

For example, the HBO miniseries Roman Empire, based on Robert Graves’ novels, extensively references Tacitus's writings. The show’s creators incorporated Tacitus’s detailed descriptions of political intrigue and societal collapse to enhance the historical authenticity of their production. Similarly, the movie Aquila Rising uses Tacitus’s accounts of Roman military campaigns to add depth and realism to its narrative.

Tacitus's works also serve as a critical foil against which modern audiences can evaluate contemporary politics. His relentless focus on the moral and ethical dimensions of leadership resonates with a wide range of readers and viewers, inviting them to reflect on the values of their own era.

Ancient Rome, as depicted by Tacitus, has become a symbol of both glory and corruption. The idea of a civilization built on lavish luxury and fragile foundations has captivated modern imaginations. Works of literature and film often use this archetypal image to explore themes of power, corruption, and societal collapse.

Moreover, Tacitus’s historical narratives have shaped the cultural zeitgeist. His descriptions of Roman customs, rituals, and social hierarchies provide a rich tapestry onto which modern storytellers can layer their interpretations. By drawing from Tacitus's detailed accounts, writers and artists can bring a sense of authenticity and historical weight to their creations.

Ultimately, Tacitus’s enduring legacy lies in his ability to capture the complexity of human nature against the backdrop of imperial power. His writings continue to challenge and inspire, prompting readers and scholars alike to examine the underlying motives and moral dilemmas that shape societies. As long as people are fascinated by the Roman Empire, Tacitus will remain a pivotal figure in the annals of historical writing.

Critical Analysis and Recent Scholarship

Recent scholarly approaches to Tacitus have sought to reconcile the historical value of his works with the critical lens through which they are perceived. Modern historians and classicists engage in rigorous analysis, seeking to understand Tacitus within the context of his times while also acknowledging the limitations of his perspective. This includes examining the social and literary contexts in which his writings were created and disseminated.

Peter Garnier, a renowned scholar of Tacitus, argues that Tacitus’s historical works should be considered within the framework of late 1st to early 2nd century AD literature. Garnier emphasizes the rhetorical and didactic purposes behind Tacitus’s writing, suggesting that his works served as a means to critique contemporary politics and morals. His analysis highlights Tacitus’s role not just as a historian, but also as a moral philosopher and polemicist.

Another important aspect of recent scholarship is the study of Tacitus’s literary techniques. Scholars such as Ronald Mellor have focused on Tacitus’s use of narrative structure, dialogue, and character development to present complex historical narratives. Mellor’s work demonstrates how Tacitus’s intricate storytelling enhances the reader’s engagement and deepens the thematic analysis of his works. These narrative techniques have influenced subsequent historians and novelists, highlighting Tacitus’s enduring impact on literary forms.

Ethical and moral critiques have also received considerable attention. Scholars like Mary Beard emphasize the importance of understanding Tacitus’s moral philosophy and its relevance to modern ethical discussions. Beard argues that Tacitus’s works offer valuable insights into the concept of moral responsibility and the ethical dimensions of historical writing. Her interpretation of Tacitus’s dialogues, such as Dialogorum, provides a fresh perspective on his philosophical musings and their resonance with contemporary debates.

Cultural and social contexts have also been explored in recent scholarly works. The University of California, Berkeley’s series on Roman cultural history has featured studies that place Tacitus within broader socio-cultural frameworks. These studies examine how Tacitus’s works reflect the changing values and social structures of the Roman Empire, providing a nuanced understanding of his historical context. Such research offers a more comprehensive view of Tacitus as a product of his time as well as a thinker who transcended his era.

Education and Public Outreach

Tacitus’s works continue to play a vital role in educational settings, serving as primary sources for the study of Roman history. In universities and classical studies programs worldwide, students engage with Tacitus’s Histories and Annals as part of their curriculum. These texts are not only central to undergraduate and graduate courses but also form the basis for advanced research in classics and history departments.

The use of Tacitus in educational settings goes beyond merely reading his texts; it involves critical analysis and discussion. Students are encouraged to question Tacitus’s sources, methods, and biases, fostering a deeper understanding of historiographical techniques. Assignments often include essay writing, comparative analyses, and oral presentations, encouraging critical thinking and scholarly debate.

Public outreach initiatives and museum exhibits also contribute to keeping Tacitus relevant. Museums such as the British Museum and the Louvre incorporate Tacitus’s works into their educational programs and displays. These initiatives aim to make Tacitus accessible to a broader audience, using multimedia resources like videos, podcasts, and interactive exhibits to engage younger generations with the complexities of Roman history.

Festivals and conferences dedicated to Tacitus and Roman history are increasingly common. Events like the International Conference on Tacitus at the University of Edinburgh and the annual Colloquium on Roman Studies at Cambridge University bring together scholars, students, and enthusiasts to discuss the latest research and engage in lively debates. These platforms not only advance the academic discourse but also foster a community of professionals and enthusiasts who share a passion for Tacitus and Roman history.

Closing Reflections

Tacitus remains a fascinating and enduring figure in the history of scholarship and literature. His complex works continue to inspire and challenge modern readers, historians, and students. Despite the ongoing scholarly debates and controversies surrounding his writings, Tacitus’s contributions to historical method and moral philosophy persist as vital components of the historian’s toolkit.

As we delve into the pages of Tacitus’s Histories and Annals, we are reminded of the intricate web of political intrigue, moral decay, and societal transformation that characterized the Roman Empire. His vivid and evocative prose, coupled with his critical and incisive analysis, ensures that Tacitus’s voice remains a resonant presence in the annals of Western historiography.

From the halls of academia to the classrooms and public forums, Tacitus continues to be a catalyst for discussion, reflection, and continued exploration of the human condition. His enduring legacy underscores the timeless relevance of his works, reminding us of our own responsibilities as thinkers, writers, and historians.

Lucius Aelius Sejanus: The Rise and Fall of Tiberius' Notorious Praetorian Prefect

Introduction: The Shadow Behind the Throne

Lucius Aelius Sejanus remains one of the most infamous figures of the early Roman Empire, a man whose ambition and cunning allowed him to rise to unprecedented power before his dramatic downfall. As the prefect of the Praetorian Guard under Emperor Tiberius, Sejanus wielded immense influence, shaping imperial politics through manipulation, conspiracy, and ruthless elimination of rivals. His story is a cautionary tale of ambition unchecked by morality and loyalty, ending in betrayal and destruction.

Early Life and Rise to Power

Born around 20 BCE in Volsinii, Etruria, Sejanus came from an equestrian family. His father, Lucius Seius Strabo, was the first commander of the Praetorian Guard under Augustus, a position that likely opened doors for his son. Sejanus joined the military early, displaying both competence and ambition. When his father was appointed governor of Egypt in 15 CE, Sejanus succeeded him as sole prefect of the Praetorian Guard under Tiberius.

The Praetorian Guard, originally a small bodyguard unit for the emperor, became increasingly powerful under Sejanus’ leadership. Recognizing their potential as a political tool, he consolidated the previously dispersed cohorts into a single camp near Rome—the Castra Praetoria. This move not only strengthened the Guard’s efficiency but also centralized its power under Sejanus’ control, making it an instrument of intimidation and enforcement for the imperial regime.

Sejanus and Tiberius: A Dangerous Partnership

Tiberius, who became emperor in 14 CE after Augustus’ death, was a reserved and often paranoid ruler. Unlike his predecessor, he disliked the public duties of the principate, preferring to retreat from Rome. This detachment created a power vacuum that Sejanus skillfully exploited. He positioned himself as Tiberius’ most trusted advisor, isolating the emperor from other influential figures while eliminating potential threats.

Sejanus’ influence over Tiberius grew as he stoked the emperor’s fears of conspiracy. The death of Tiberius’ son, Drusus Julius Caesar, in 23 CE, further deepened the emperor’s dependence on Sejanus. Rumors later emerged that Sejanus had poisoned Drusus, though historical evidence remains inconclusive. Regardless, Drusus’ death removed a significant obstacle to Sejanus' ambitions, as he began positioning himself as Tiberius’ successor.

The Elimination of Rivals: A Reign of Terror

Sejanus' most notorious legacy is his role in the political purges that marked Tiberius’ reign. Using accusations of treason (maiestas), he targeted senators, aristocrats, and even members of the imperial family. Trials became spectacles of fear, with many condemned on flimsy evidence or forced confessions. Among his victims was Agrippina the Elder, granddaughter of Augustus and mother of Caligula, whom Sejanus saw as a threat due to her popularity and lineage.

The trials served multiple purposes: they secured Sejanus’ dominance by removing rivals, enriched the treasury through confiscated estates, and reinforced Tiberius’ growing paranoia. The Senate, cowed into submission, became an instrument of Sejanus’ will. His power reached its zenith in 31 CE when he was named co-consul with Tiberius—an unprecedented honor for an equestrian—and betrothed to Livilla, sister of the late Drusus and a woman with strong ties to the imperial family.

The Beginning of the End: Tiberius’ Mistrust

Despite his apparent invincibility, Sejanus’ downfall was set in motion by his own overreach. His ambition to marry into the imperial family and possibly claim the throne made Tiberius increasingly wary. The emperor, now residing in self-imposed exile on Capri, began receiving warnings about Sejanus from his sister-in-law, Antonia Minor, and his trusted freedman, Macro.

Tiberius, though cautious, was not blind to Sejanus’ machinations. In a masterstroke of deception, he lulled Sejanus into a false sense of security, even hinting at granting him greater honors. Meanwhile, he secretly prepared for the prefect’s downfall, transferring some of the Praetorian Guard’s loyalty to Macro.

The Dramatic Fall of Sejanus

On October 18, 31 CE, the Senate convened under the pretense of granting Sejanus additional powers. Instead, they were presented with a letter from Tiberius denouncing his former favorite as a traitor. Macro, now in command of the Guard, arrested Sejanus on the spot. The public reaction was swift and brutal. The man who had ruled Rome through fear was now subject to its wrath—dragged through the streets, lynched by the mob, and his body thrown into the Tiber.

The aftermath was a bloodbath. Sejanus’ family and supporters were executed, including his young children. His name was erased from monuments, a damnatio memoriae ensuring his disgrace would be remembered for centuries.

The Aftermath of Sejanus' Downfall: A Reign of Paranoia

The execution of Sejanus did not bring stability to Rome—instead, it deepened Tiberius’ paranoia. The emperor, already distrustful of the Senate and the aristocracy, now saw conspiracies everywhere. The trials and purges that had defined Sejanus’ rise continued, but without his guiding hand, they became even more indiscriminate. Tiberius relied heavily on informers (delatores) to root out perceived enemies, leading to a climate of fear where accusations alone could doom entire families.

Sejanus' elimination also left a power vacuum. Macro, his successor as Praetorian prefect, wielded significant influence but lacked Sejanus’ political cunning. Meanwhile, the surviving members of the imperial family, particularly Agrippina the Elder’s children, faced renewed persecution. Tiberius' suspicion of them as potential rivals only intensified, leading to their imprisonment or exile. The once-proud Julio-Claudian dynasty was fracturing under the weight of mistrust.

The Role of the Praetorian Guard in Imperial Politics

Sejanus’ impact on the Praetorian Guard was lasting. Before his time, the Guard had been a relatively passive military unit, but under his leadership, it became a dominant political force. His consolidation of the Guard into a single camp permanently altered its role in Roman governance. Future emperors would recognize the Praetorians as kingmakers—capable of both protecting and overthrowing rulers.

The Guard’s loyalty was no longer guaranteed by tradition but had to be bought with privileges, bonuses, and political concessions. This shift set a dangerous precedent; later emperors, such as Caligula and Nero, would face revolts instigated by discontented Praetorians. The Guard’s involvement in imperial succession became so normalized that assassination plots often originated within its ranks.

The Psychological Profile of Sejanus: Ambition Without Limits

What drove Sejanus to such extremes of treachery? Ancient historians like Tacitus and Cassius Dio depict him as a man consumed by ambition, willing to betray anyone to secure power. Unlike earlier Roman statesmen, who sought glory through public service or military conquest, Sejanus pursued influence through subterfuge and manipulation. His rise reflected the darker side of imperial politics, where loyalty was transactional and morality was secondary to survival.

Yet, some historians argue that Sejanus may have been unfairly scapegoated. Tiberius, who had allowed—and even encouraged—his prefect’s actions, later used him as a convenient villain to explain the bloodshed of his reign. The truth likely lies somewhere in between: Sejanus was undoubtedly ruthless, but he also operated within a system already poisoned by suspicion and ambition.

Sejanus and the Women of the Imperial Court

One often overlooked aspect of Sejanus’ rise was his relationship with influential women in Tiberius’ circle. The most notable was Livilla, Drusus’ widow and sister of the future emperor Claudius. Rumors persist that she conspired with Sejanus to poison her husband, clearing the path for their alliance. If true, this would mark one of the earliest instances of a Roman noblewoman engaging in political murder—a chilling foreshadowing of later imperial intrigues.

Similarly, Antonia Minor, mother of the future emperor Claudius, played a crucial role in Sejanus’ downfall. Recognizing his threat, she reportedly sent a trusted servant to warn Tiberius on Capri. This intervention highlights the often-hidden but powerful influence of imperial women, who could shape events from behind the scenes.

The Legacy of Fear: Sejanus’ Impact on Tiberius’ Later Years

Even after Sejanus' death, his specter haunted Tiberius’ reign. The emperor withdrew further from Rome, ruling through letters and proxies from his island retreat on Capri. The later years of his rule were marked by near-tyranny, with executions becoming so frequent that senators attended meetings under fear of sudden arrest. Tiberius’ isolation and paranoia only worsened, leading some to speculate that he regretted allowing Sejanus’ rise in the first place.

Sejanus’ downfall also destabilized the imperial succession. With Tiberius’ biological heirs dead or disgraced, the aging emperor was forced to consider alternative successors, ultimately favoring his young grandnephew, Caligula. The chaotic transition after Tiberius’ death in 37 CE demonstrated how deeply Sejanus’ machinations had disrupted the dynasty’s stability.

The Historiography of Sejanus: Victim or Villain?

Ancient historians, particularly Tacitus and Suetonius, portray Sejanus as a power-hungry schemer whose treachery knew no bounds. Yet modern scholars debate whether this depiction is entirely fair. The senatorial class, whose members suffered greatly under Tiberius’ reign, had every reason to vilify Sejanus as the architect of their woes. Meanwhile, Tiberius, who outlived his disgraced prefect, ensured that official records cast Sejanus as the sole instigator of the terror.

Some historians suggest that Sejanus may have initially acted with Tiberius’ tacit approval, only to later take the blame when the emperor sought to distance himself from the brutality of his regime. This interpretation paints a more complex picture of Sejanus—not merely as a villain, but as a product of a system that rewarded ruthlessness and punished failure mercilessly.

Regardless of the interpretation, Sejanus remains a defining figure of the early empire, illustrating how easily absolute power could corrupt even the most cunning of men.

The Final Years of Tiberius and the Legacy of Sejanus

In the years following Sejanus' execution, Tiberius' reign continued to be marked by suspicion and repression. The emperor, now in his seventies, became increasingly reclusive, ruling from his villa on Capri. His paranoia grew to such an extent that he reportedly had his own servants executed on mere suspicion of disloyalty. The political climate in Rome remained tense, with the Senate and the aristocracy living in constant fear of accusations and purges. The once-great city had become a place where trust was a rare commodity, and survival depended on one's ability to navigate the treacherous waters of imperial politics.

Despite his advanced age, Tiberius showed no signs of relinquishing power. He continued to govern through a network of trusted officials, though none ever achieved the same level of influence as Sejanus. The emperor's distrust of potential successors was evident in his treatment of his grandnephew, Caligula. Though Tiberius eventually named Caligula as his heir, he kept him under close watch, wary of any signs of ambition. This atmosphere of suspicion would have lasting consequences for the Roman Empire, setting a precedent for future emperors who would rule with an iron fist.

Caligula's Rise and the Shadow of Sejanus

When Tiberius died in 37 CE, Caligula ascended to the throne, marking the beginning of a new era. However, the specter of Sejanus loomed large over the early days of his reign. Caligula, who had witnessed firsthand the purges and betrayals of Tiberius' rule, was determined to avoid the same fate. He moved quickly to consolidate power, executing potential rivals and rewarding those who had supported his rise. Yet, his reign would soon spiral into tyranny, demonstrating how the lessons of Sejanus' era had been forgotten.

Caligula's erratic behavior and brutal rule shocked even the jaded citizens of Rome. His excesses, including his self-deification and the execution of senators on whims, made Tiberius' reign seem almost moderate by comparison. Some historians argue that Caligula's paranoia and cruelty were exacerbated by the trauma of growing up in the shadow of Sejanus' conspiracies. The young emperor had seen how easily power could be seized and how quickly allies could become enemies. His reign, though short, would leave an indelible mark on the empire, further eroding the already fragile trust between the emperor and the Senate.

The Long-Term Impact of Sejanus on Roman Politics

Sejanus' influence extended far beyond his lifetime, shaping the political landscape of Rome for decades. His rise and fall demonstrated the dangers of concentrating too much power in the hands of a single individual, particularly one outside the traditional aristocracy. The Praetorian Guard, which he had transformed into a political force, would continue to play a pivotal role in imperial succession, often acting as kingmakers. The Guard's involvement in politics became so normalized that future emperors had to constantly court their favor to maintain power.

Moreover, Sejanus' methods of governance—using fear, manipulation, and purges to maintain control—became a template for future rulers. Emperors like Nero and Domitian would employ similar tactics, leading to periods of intense repression. The Senate, once a respected institution, was reduced to a rubber stamp, its members too afraid to challenge the emperor's will. The erosion of republican values, which had begun under Augustus, accelerated under Tiberius and Sejanus, paving the way for the autocratic rule of later emperors.

Sejanus in Popular Culture and Historical Memory

Sejanus' story has captured the imagination of writers and historians for centuries. His life has been the subject of numerous plays, novels, and films, often portrayed as a cautionary tale of ambition and betrayal. The 17th-century playwright Ben Jonson wrote a tragedy titled *Sejanus His Fall*, which dramatizes his rise and downfall. In modern times, he has appeared in historical fiction and television series, often as a scheming villain who embodies the corruption of power.

Historians continue to debate Sejanus' true motives and legacy. Some view him as a ruthless opportunist who exploited Tiberius' paranoia for personal gain. Others argue that he was a product of a broken system, one that rewarded treachery and punished loyalty. Regardless of the interpretation, Sejanus remains a fascinating figure—a man who came closer to the throne than any non-imperial Roman and whose actions reshaped the course of history.

Conclusion: The Enduring Lessons of Sejanus' Rise and Fall

The story of Sejanus is more than just a tale of ambition and betrayal—it is a reflection of the dangers of unchecked power and the fragility of political systems. His rise to prominence under Tiberius revealed the vulnerabilities of the early Roman Empire, where loyalty was fleeting and survival depended on one's ability to navigate a web of intrigue. His downfall, swift and brutal, demonstrated the precariousness of power built on fear and manipulation.

Sejanus' legacy serves as a warning to future generations about the perils of absolute power and the corrosive effects of paranoia. His life reminds us that even the mightiest can fall when they overreach, and that the pursuit of power at any cost often leads to destruction. In the end, Sejanus' story is not just a chapter in Roman history—it is a timeless lesson about the nature of ambition, loyalty, and the price of power.

Constantine the Great: The Visionary Emperor Who Shaped History

Introduction: The Rise of a Legendary Leader

Constantine the Great, born Flavius Valerius Constantinus, stands as one of the most influential figures in world history. His reign marked a pivotal turning point for the Roman Empire, setting the stage for the rise of Christianity and the transformation of European civilization. Born in Naissus (modern-day Niš, Serbia) around AD 272, Constantine emerged from the turbulent period known as the Crisis of the Third Century to become the sole ruler of the Roman Empire.

This first part of our exploration will examine Constantine's early life, his path to power, and the military campaigns that established his dominance. We'll also explore the famous vision that changed the course of religious history and examine his political reforms that reshaped the empire's administration.

Early Life and the Tetrarchy System

Constantine was born to Constantius Chlorus, a Roman officer who would later become one of the four rulers in Diocletian's Tetrarchy system, and Helena, a woman of humble origins who would later be venerated as Saint Helena. Growing up in the imperial court, Constantine received a thorough education in Latin, Greek, and military strategy. His early years were spent in the eastern part of the empire, where he witnessed firsthand the workings of Diocletian's government.

The Tetrarchy system, established by Diocletian in 293, divided imperial power among four rulers: two senior Augusti and two junior Caesares. This system aimed to provide better governance for the vast empire and ensure smooth succession. Constantine's father Constantius became one of the Caesars, ruling the western provinces of Gaul and Britain.

Constantine's Path to Power

When Constantius died in 306 while campaigning in Britain, the army immediately proclaimed Constantine as Augustus. This act violated the Tetrarchy's succession rules, leading to years of conflict among rival claimants. Constantine initially accepted the lesser title of Caesar to maintain peace but gradually consolidated his power through military victories and political alliances.

One of Constantine's most significant early achievements was his campaign against the Franks in 306-307, where he demonstrated his military prowess. He then strengthened his position by marrying Fausta, daughter of the senior Augustus Maximian, in 307. This marriage alliance connected him to the imperial family and provided legitimacy to his rule.

The Battle of the Milvian Bridge and the Christian Vision

The turning point in Constantine's career came in 312 at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge against his rival Maxentius. According to Christian sources, Constantine had a vision before the battle where he saw a cross in the sky with the words "In hoc signo vinces" ("In this sign, you shall conquer"). He ordered his soldiers to paint the Chi-Rho symbol (☧) on their shields and emerged victorious against overwhelming odds.

This victory made Constantine the sole ruler of the Western Roman Empire and marked the beginning of his support for Christianity. While the exact nature of his conversion remains debated among historians, the Edict of Milan in 313, which he issued jointly with Licinius, granted religious tolerance throughout the empire and ended the persecution of Christians.

Consolidation of Power and Administrative Reforms

After defeating Licinius in 324, Constantine became the sole ruler of the entire Roman Empire. He immediately set about implementing significant reforms that would transform the empire's structure:

- He established a new capital at Byzantium, which he renamed Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul)

- He reorganized the military, creating mobile field armies and separating military and civilian administration

- He reformed the currency with the introduction of the gold solidus

- He restructured provincial administration, increasing the number of provinces and creating the diocesan system

These reforms strengthened the empire's governance and laid the foundation for what would later become the Byzantine Empire.

Constantine and Christianity

Constantine's relationship with Christianity was complex and evolved throughout his reign. While he never made Christianity the official state religion, he gave it significant privileges and actively supported the Church. He:

- Funded the construction of important churches, including the original St. Peter's Basilica in Rome

- Exempted clergy from taxation and civic duties

- Intervened in theological disputes, convening the First Council of Nicaea in 325

- Promoted Christians to high offices in his administration

At the same time, Constantine maintained some traditional Roman religious practices and was only baptized on his deathbed, a common practice at the time among those who feared post-baptismal sin.

Legacy of the First Christian Emperor

By the time of his death in 337, Constantine had transformed the Roman Empire in fundamental ways. His reign marked the transition from classical antiquity to the medieval period and set the stage for the Byzantine Empire. The city he founded, Constantinople, would remain a center of power for over a thousand years.

Constantine's support for Christianity had profound consequences for European history, making the religion a dominant force in Western civilization. His political and military reforms helped stabilize the empire during a period of crisis, though some historians argue they also contributed to the eventual division between East and West.

This concludes our first part on Constantine the Great. In the next section, we will explore in greater depth his religious policies, the founding of Constantinople, and his complex personal life and family relationships that would shape the empire's future after his death.

The Religious Transformation: Constantine's Christian Policies

Constantine's approach to Christianity was neither immediate nor absolute. His policies represented a gradual shift that balanced imperial tradition with the growing influence of the Christian faith. Following the Edict of Milan in 313, Constantine implemented measures that deeply altered the religious landscape of the empire:

- He returned confiscated Christian property seized during previous persecutions

- Granted tax exemptions and financial support to Christian clergy

- Gave bishops judicial authority within their communities

- Established Sunday as an official day of rest in 321

- Banned certain pagan practices while maintaining the title of Pontifex Maximus

This calculated approach allowed Christianity to flourish while preventing immediate upheaval of traditional Roman religion. Constantine's personal faith remains complex—he continued to use ambiguous religious language in official documents and maintained elements of solar monotheism (Sol Invictus) in his imagery.

The First Council of Nicaea (325 AD)

Constantine's most significant religious intervention came with the Arian controversy regarding the nature of Christ. To settle the dispute, he convened the First Ecumenical Council at Nicaea:

- Brought together approximately 300 bishops from across the empire

- Personally inaugurated the council, though not baptized himself

- Resulted in the Nicene Creed establishing orthodox doctrine

- Created a precedent for imperial involvement in church affairs

The council demonstrated Constantine's desire for religious unity as a stabilizing force and established the framework for Christian orthodoxy that would endure for centuries.

The New Rome: Founding of Constantinople

In 324, Constantine began his most ambitious project—the transformation of the ancient Greek city Byzantium into a new imperial capital. Officially dedicated on May 11, 330, Constantinople was designed as:

- A strategically located capital at the crossroads of Europe and Asia

- A Christian alternative to pagan Rome with churches instead of temples

- A fortress city with expanded walls and natural defenses

- A center of culture and learning with imported artworks and scholars

Urban Planning and Symbolism

Constantine's architects employed sophisticated urban design to create a city that would rival and eventually surpass Rome:

- Laid out the city on seven hills like Rome, with fourteen districts

- Created the monumental Mese, a colonnaded main street

- Erected the Milion as the symbolic center of the empire's road network

- Constructed the Great Palace complex as the imperial residence

The city's Christian character was emphasized through prominent churches and the absence of pagan temples, though some traditional civic structures were maintained for practical purposes.

Military Reforms and Frontier Defense

Recognizing the empire's security challenges, Constantine reshaped Rome's military structure:

| Reform | Description | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Field Armies | Created mobile strike forces (comitatenses) | Allowed rapid response to border threats |

| Border Forces | Strengthened limitanei frontier troops | Provided static defense of imperial borders |

| New Units | Introduced cavalry-heavy formations | Countered growing threat from mounted enemies |

These reforms maintained imperial security but also had long-term consequences, including increased military spending and greater separation between civilian and military authority.

Constantine's Family Dynamics

The imperial household was both Constantine's greatest strength and his tragic weakness. His marriage to Fausta produced five children who would play crucial roles in his succession plans. However, multiple family crises marked his reign:

The Crisis of 326

This pivotal year saw the execution of Constantine's eldest son Crispus and shortly after, his wife Fausta under mysterious circumstances:

- Crispus had been a successful general and heir apparent

- Ancient sources suggest Fausta may have falsely accused Crispus

- The scandal necessitated rewriting Constantine's succession plans

- Three surviving sons (Constantine II, Constantius II, Constans) became new heirs

The Imperial Succession

Constantine developed an ambitious plan to divide power while maintaining dynastic unity:

- Appointed his sons as Caesars during his lifetime

- Created a network of cousins to administer provinces

- Established Constantinople as neutral territory under Senate control

- This complex system quickly collapsed after his death in 337

Legal and Social Reforms

Constantine's legal enactments reflected both traditional Roman values and Christian influence:

| Area | Reform | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Slavery | Restricted separation of slave families | Reflected Christian ethics |

| Marriage | Strict penalties for adultery | Moral legislation |

| Crime | Crucifixion abolished | Symbolic Christian reform |

| Wills | Recognized validity of Christian wills | Legal status for Christian practice |

While these reforms improved conditions for some, Constantine also enacted harsh penalties, including branding and amputation, for certain offenses.

Preparing for the Next Part

In this second part, we've examined Constantine's complex religious policies, the monumental founding of Constantinople, critical military reforms, and fascinating family dynamics. As we conclude this section, we've laid the groundwork for understanding how Constantine's reign fundamentally transformed the Roman world.

Our third and final installment will explore Constantine's final years, his baptism and death, the immediate aftermath of his reign, and the lasting impact of his rule on Western civilization. We'll examine how his successors managed—or failed to maintain—his vision and how modern historians assess his complex legacy.

The Final Years and Legacy of Constantine the Great

The Road to Baptism and Death

In his later years, Constantine prepared for what he believed would be his most important transition - the passage from earthly power to eternal salvation. Following contemporary Christian practice that feared post-baptismal sin, he postponed his baptism until he fell seriously ill near the end of his life. This final act occurred in 337 at the suburban villa of Ancyrona near Nicomedia when:

- He was baptized by the Arian bishop Eusebius of Nicomedia

- Chose to be clothed in white baptismal robes rather than his imperial purple

- Reportedly refused to wear his imperial insignia afterward

- Died shortly thereafter on May 22, 337, at approximately age 65

The Imperial Succession and Family Conflict

Constantine's carefully planned succession quickly unraveled after his death. The empire became embroiled in a bloody transition period that revealed the fragility of his dynastic vision:

| Successor | Territory | Fate |

|---|---|---|

| Constantine II | Gaul, Britain, Spain | Killed in 340 invading Constans' territory |

| Constantius II | Eastern provinces | Became sole emperor by 353 |

| Constans | Italy, Africa | Assassinated in 350 |

The power struggle extended to Constantine's extended family, with most male relatives murdered within months of his death in a purge likely ordered by Constantius II. This tragic outcome contrasted sharply with Constantine's hopes for dynastic continuity.

The Milvian Bridge Legacy: Christianity's Imperial Future

Constantine's support for Christianity set in motion changes that would far outlive his empire:

- The Christian church gained legal status and eventually became the state religion under Theodosius I

- Ecclesiastical structures mirrored imperial administration

- Christian theology became intertwined with Roman imperial ideology

- The bishop of Rome (the Pope) gained increasing political authority

The Donation of Constantine Controversy

Centuries after his death, an eighth-century document called the "Donation of Constantine" purported to record Constantine giving temporal power over Rome and the western empire to Pope Sylvester I. While proved a medieval forgery in the 15th century, it:

- Influenced papal claims to political authority throughout the Middle Ages

- Became a key document in church-state conflicts

- Demonstrated Constantine's lasting symbolic importance to the Catholic Church

Constantinople: The Enduring City

Constantine's "New Rome" outlasted the Western Roman Empire by nearly a thousand years, becoming:

- The capital of the Byzantine Empire until 1453

- A bulwark against eastern invasions of Europe

- The center of Orthodox Christianity

- A cosmopolitan hub of commerce, culture, and learning

Even after its fall to the Ottomans, the city (renamed Istanbul) remained a major world capital, maintaining elements of Constantine's urban design into modern times.

Military and Administrative Aftermath

Constantine's reforms established patterns that defined later Byzantine governance:

| Reform | Long-term Impact |

|---|---|

| Separate military commands | Became standard in medieval European states |

| Mobile field armies | Precursor to later Byzantine tagmata forces |

| Gold solidus currency | Remained stable for 700 years |

| Regional prefectures | Influenced medieval administrative divisions |

Historical Assessment and Modern Views

Historians continue to debate Constantine's legacy:

The Christian Hero Narrative

Traditional Christian historiography views Constantine as:

- The emperor who ended persecution

- A divinely inspired leader

- The founder of Christian Europe

The Pragmatic Politician Interpretation

Modern secular scholarship often emphasizes:

- His manipulation of religion for political unity

- The continuities with earlier imperial systems

- His military and administrative skills

The Ambiguous Legacy

Most contemporary historians recognize:

- Both genuine faith and political calculation in his policies

- His central role in Europe's Christianization

- The unintended consequences of his reforms

Constantine in Art and Culture

The first Christian emperor became an enduring cultural symbol:

Medieval Depictions

- Featured in Byzantine mosaics and manuscripts

- Central to Crusader ideology

- Subject of medieval romance literature

Renaissance and Baroque Art

- The Vision of Constantine became popular subject

- Depicted in Raphael's "The Baptism of Constantine"

- Sculptures in major European churches

Modern Representations

- Appears in films and television series

- Subject of historical novels

- Inspiration for Christian political movements

Conclusion: The Architect of a New World

Constantine the Great stands as one of history's pivotal figures whose decisions fundamentally altered the course of Western civilization. By combining Roman imperial tradition with Christian faith, military prowess with administrative genius, and dynastic ambition with strategic vision, he created a synthesis that would endure for centuries. Though his immediate successors failed to maintain his vision perfectly, the foundations he laid—the Christian Roman Empire, the city of Constantinople, and new models of governance—shaped medieval Europe and influence our world today.

From the Roman persecutions to the edicts of tolerance, from the old Rome to the new, from pagan empire to Christian state, Constantine presided over one of history's great transitions. His life reminds us that individual leaders can indeed change the world, though often in ways more complex than they could foresee. Whether viewed as saint, opportunist, or simply as one of Rome's greatest emperors, Constantine's impact on religion, politics, and culture remains undeniable more than sixteen centuries after his death.

Aetius: The Last of the Great Roman Generals

The decline of the Roman Empire was marked by an era of turbulence and transformation, characterized by internal strife, external threats, and the sweeping changes that would reshape the ancient world. Amidst the chaos, one military genius emerged as a formidable force standing between Rome and its numerous adversaries. Flavius Aetius, often referred to as the "Last of the Romans," is remembered as one of antiquity's most skilled and resilient generals. His life and career encapsulate the challenges and complexities of a civilization teetering on the brink of collapse.

Early Life and Rise to Power

Born around 391 AD in Durostorum, present-day Silistra, Bulgaria, Aetius was thrust into a world of shifting allegiances and power struggles. His father, Flavius Gaudentius, was an influential military officer of Scythian origin, while his mother hailed from a noble Italian family. This unique heritage provided Aetius with advantageous connections and a comprehensive understanding of Roman and barbarian cultures alike.

Aetius spent a significant part of his youth living as a diplomatic hostage among the Goths and then with the Huns. This exposure to barbarian customs and military tactics would prove invaluable in his later military career. The relationships he forged during these formative years granted him a rare ability to navigate the complex web of alliances and enmities that defined the era.

Rising through the ranks, Aetius's early military career was marked by both skill and political acumen. By the early 420s, he had earned the title of magister equitum, or Master of Soldiers, for the Western Roman Empire. His strategic insight and leadership abilities gained him the favor of Emperor Valentinian III, though his ascent was not without challenges. Aetius's path to power was fraught with conflict and competition, most notably with his rival, Bonifacius, another prominent Roman general.

The Battle of the Catalaunian Plains

The defining moment of Aetius's career—and one of the most pivotal battles of Late Antiquity—came in 451 AD at the Catalaunian Plains, near modern-day Châlons-en-Champagne in France. This confrontation saw Aetius leading a coalition of Roman forces and their barbarian allies against the fearsome Huns, under the command of the formidable Attila.

Aetius's knowledge of Hunnic tactics, gleaned from his years of captivity, proved instrumental in his planning. By coordinating an alliance with the Visigoths and other Germanic tribes, Aetius managed to assemble a formidable army. The ensuing battle was brutal and chaotic, with both sides suffering substantial casualties. Although the victory was not decisive in the traditional sense—since Attila's forces were not completely annihilated—it was a significant setback for the Huns, halting their advance into Western Europe and preserving Roman territories for a while longer.

The battle remains one of the last significant achievements of the Western Roman military, and Aetius was lauded for his capacity to unify disparate factions against a common enemy, cementing his reputation as a masterful tactician and diplomat.

Political Intrigue and Downfall

Despite his military success, Aetius's life was characterized by the enigmatic and treacherous political landscape of the Roman court. His relationship with Emperor Valentinian III, while mutually beneficial, was also strained by jealousy and mistrust. Aetius wielded immense influence over Western Roman affairs, a power which, ironically, led to his undoing.

In 454 AD, amidst growing suspicion and rivalry, Valentinian III feared that Aetius might seize imperial power for himself. Driven by paranoia or perhaps convinced by court intrigue, the emperor, during a heated meeting, unexpectedly struck down Aetius with his own hand, delivering a fatal blow to one of Rome's last stalwart defenders.

This assassination marked a turning point in Roman history. Without Aetius's guiding hand, the Western Roman Empire struggled to fend off incursions and maintain cohesion. His death left a vacuum of military leadership which made it increasingly difficult for Rome to resist the growing threats from external forces.

Legacy of Aetius

The legacy of Flavius Aetius is a testament to his capabilities as a military leader and a statesman of rare talent. Historians often regard him as one of the last skilled generalissimos of the Western Roman Empire, whose actions, though they could not prevent the eventual fall of Rome, delayed the inevitable decline and left a lasting impression on the European historical narrative.

Despite the turbulent and often violent world in which he lived, Aetius demonstrated an unparalleled ability to wield power with a deft hand. His capacity to forge alliances and outmaneuver military foes fortified Roman territories temporarily, if not permanently, and exemplified the strategic acumen that defined his storied career.

Flavius Aetius's journey from a hostage of the Huns to one of Rome's most celebrated defenders highlights the intricate dance of diplomacy, warfare, and politics that characterized the final chapters of the Roman Empire. As modern historians continue to explore the extensive evidence of his exploits, Aetius's story remains a compelling testament to the complex tapestry of loyalty, valor, and ambition that defined an era of profound transformation.

Aetius and the Fabric of Roman Society

A deeper look into the life and career of Flavius Aetius reveals the turbulent socio-political landscape of the late Roman Empire—a time when the very foundations of Roman society were being tested by both internal decay and external pressures. Aetius, through his strategic and diplomatic maneuvering, exemplified the tenuous balance between maintaining traditional Roman authority and adapting to a rapidly changing world.

During Aetius's lifetime, the Roman Empire was grappling with a variety of considerable challenges. Political corruption, economic instability, and military setbacks had weakened the once formidable power of Rome. The empire's territory, divided administratively into Eastern and Western halves, was further strained by the challenges of governance, with the Western Roman Empire suffering more acutely from these ailments. It was in this fraught environment that Aetius rose to prominence, his abilities and experiences standing out as indispensable assets to an empire teetering on the brink.

Diplomacy and Alliances

One of Aetius's most remarkable attributes was his keen diplomatic sense and his ability to form strategic alliances. At a time when barbarian kingdoms were not only frontier threats but significant political entities, Aetius understood the necessity of collaboration. His alliances extended beyond the battlefield and into the domain of diplomacy, where his ability to negotiate and maintain relationships became crucial to Roman interests.

His alliance with the Visigoths, illustrated during the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains, stands as a testament to his diplomatic prowess. By convincing the Visigoths to fight alongside Roman forces against Attila's Huns, Aetius demonstrated a rare and essential ability to bridge the gap between Rome and its traditional adversaries. This coalition was not merely a tactical necessity; it pointed to an evolving understanding of power in the late ancient world, predicated on cooperation as much as it was on conquest.

Aetius's time among the Huns in his youth had equipped him with an intimate knowledge of their culture and strategies, which in turn informed his diplomatic actions. This insider insight allowed Aetius to navigate the complex diplomatic landscape and maintain a system of checks and balances that was crucial for the Western Roman Empire's survival.

Military Genius and Strategy

As a military strategist, Aetius's legacy is one of adaptability and tactical ingenuity. His ability to control and direct forces across various theaters of war, dealing with both internal revolts and external invasions, highlighted his strategic brilliance. In the face of formidable foes, such as the Visigoths, Burgundians, and Franks, Aetius combined his intuitive understanding of enemy tactics with the disciplined structure of the Roman military system.