Ptolemy: The Ancient Scholar Who Mapped the Heavens and the Earth

Introduction

Claudius Ptolemy, commonly known simply as Ptolemy, was one of the most influential scholars of the ancient world. A mathematician, astronomer, geographer, and astrologer, his works shaped scientific thought for over a millennium. Living in Alexandria during the 2nd century CE, Ptolemy synthesized and expanded upon the knowledge of his predecessors, creating comprehensive systems that dominated European and Islamic scholarship until the Renaissance. His contributions to astronomy, geography, and the understanding of the cosmos left an indelible mark on history.

Life and Historical Context

Little is known about Ptolemy’s personal life, but historical evidence suggests he was active between 127 and 168 CE. Alexandria, then part of Roman Egypt, was a thriving center of learning, home to the famed Library of Alexandria, which housed countless scrolls of ancient wisdom. Ptolemy benefited from this intellectual environment, drawing from Greek, Babylonian, and Egyptian sources to develop his theories.

His name, Claudius Ptolemaeus, indicates Roman citizenship, possibly granted to his family by Emperor Claudius or Nero. Though his ethnicity remains uncertain—whether Greek, Egyptian, or a mix—his works were written in Greek, the scholarly language of the time.

Ptolemy’s Astronomical Contributions

Ptolemy’s most famous work, the AlmagestMathematike Syntaxis), became the cornerstone of astronomy for centuries. In it, he synthesized the ideas of earlier astronomers like Hipparchus and introduced a sophisticated mathematical model of the universe.

The Ptolemaic System

Ptolemy’s geocentric model placed Earth at the center of the universe, with the Sun, Moon, planets, and stars orbiting around it in complex paths. To explain the irregular movements of planets (such as retrograde motion), he introduced mathematical concepts like epicycles—small circles within larger orbits—and eccentric orbits. While his system was later challenged by Copernicus’ heliocentric model, it provided remarkably accurate predictions for its time.

Star Catalog and Constellations

In the Almagest, Ptolemy also compiled a star catalog, listing over 1,000 stars with their positions and magnitudes. Many of the 48 constellations he described are still recognized today in modern astronomy.

Ptolemy’s Geographical Legacy

Beyond astronomy, Ptolemy made lasting contributions to geography through his work Geographia. This treatise compiled extensive knowledge about the known world, combining maps with coordinates based on latitude and longitude—a revolutionary concept at the time.

Mapping the World

Ptolemy’s maps, though flawed by modern standards due to limited exploration, provided the most detailed geographical reference of the ancient world. He estimated Earth’s size, though his calculations were smaller than Eratosthenes’ earlier (and more accurate) measurements. Despite errors, his methodology laid the groundwork for later cartographers.

Influence on Exploration

Centuries later, during the Age of Discovery, Ptolemy’s Geographia regained prominence. Explorers like Columbus relied on his maps, though some inaccuracies—such as an underestimated Earth circumference—may have influenced voyages based on miscalculations.

Ptolemy and Astrology

Ptolemy also contributed to astrology with his work Tetrabiblos ("Four Books"). While modern science dismisses astrology, in antiquity, it was considered a legitimate field of study. Ptolemy sought to systematize astrological practices, linking celestial movements to human affairs in a structured way.

The Role of Astrology in Antiquity

Unlike modern horoscopes, Ptolemy’s approach was more deterministic, emphasizing celestial influences on climate, geography, and broad human tendencies rather than personal fate. His work remained a key astrological reference well into the Renaissance.

Criticism and Legacy

While Ptolemy’s models were groundbreaking, they were not without flaws. His geocentric system, though mathematically elegant, was fundamentally incorrect. Later astronomers like Copernicus and Galileo would dismantle it, leading to the Scientific Revolution.

Yet, Ptolemy’s genius lay in his ability to synthesize and refine existing knowledge. His works preserved and transmitted ancient wisdom to future generations, bridging gaps between civilizations. Even when his theories were superseded, his methodological rigor inspired later scientists.

Conclusion (Part 1)

Ptolemy stands as a towering figure in the history of science, blending meticulous observation with mathematical precision. His geocentric model and maps may no longer hold scientific weight, but his contributions laid essential groundwork for astronomy, geography, and even early astrology. In the next part, we will delve deeper into the technical aspects of his astronomical models, their historical reception, and how later scholars built upon—or challenged—his ideas. Stay tuned as we continue exploring the enduring legacy of Claudius Ptolemy.

The Technical Brilliance of Ptolemy’s Astronomical Models

Ptolemy’s geocentric model was not merely a philosophical assertion but a meticulously crafted mathematical system designed to explain and predict celestial phenomena. His use of epicycles, deferents, and equants demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of geometry and trigonometry, allowing him to account for the irregularities in planetary motion that had puzzled earlier astronomers.

Epicycles and Deferents

At the heart of Ptolemy’s model were two principal components: the deferent, a large circular orbit around the Earth, and the epicycle, a smaller circle on which the planet moved while simultaneously revolving around the deferent. This dual-motion concept elegantly explained why planets sometimes appeared to move backward (retrograde motion) when observed from Earth. Though later proven unnecessary in a heliocentric framework, this system was remarkably accurate for its time.

The Equant Controversy

One of Ptolemy’s more controversial innovations was the equant point, a mathematical adjustment that allowed planets to move at varying speeds along their orbits. Instead of moving uniformly around the center of the deferent, a planet’s angular speed appeared constant when measured from the equant—a point offset from Earth. While this preserved the principle of uniform circular motion (sacred in ancient Greek astronomy), it also introduced asymmetry, troubling later astronomers like Copernicus, who sought a more harmonious celestial mechanics.

Ptolemy vs. Earlier Greek Astronomers

Ptolemy was indebted to earlier astronomers, particularly Hipparchus of Nicaea (2nd century BCE), whose lost works likely inspired much of the Almagest. However, Ptolemy refined and expanded these ideas with greater precision, incorporating Babylonian eclipse records and improving star catalogs. His work was less about radical innovation and more about consolidation—turning raw observational data into a cohesive, predictive framework.

Aristotle’s Influence

Ptolemy’s cosmology also embraced Aristotelian physics, which posited that celestial bodies were embedded in nested crystalline spheres. While Ptolemy’s mathematical models did not strictly depend on this physical structure, his alignment with Aristotle helped his system gain philosophical legitimacy in medieval Europe.

Transmission and Influence in the Islamic World

Ptolemy’s works did not fade after antiquity. Instead, they were preserved, translated, and enhanced by scholars in the Islamic Golden Age. The Almagest (from the Arabic al-Majisti) became a foundational text for astronomers like Al-Battani and Ibn al-Haytham, who refined his planetary tables and critiqued his equant model.

Critiques and Improvements

Islamic astronomers noticed discrepancies in Ptolemy’s predictions, particularly in Mercury’s orbit. In the 13th century, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi developed the Tusi couple, a mathematical device to generate linear motion from circular motions, which later influenced Copernicus. Meanwhile, Ibn al-Shatir’s 14th-century models replaced Ptolemy’s equant with epicycles that adhered more closely to uniform circular motion—anticipating elements of Copernican theory.

Ptolemy’s Geography: Achievements and Errors

Returning to Ptolemy’s Geographia, his ambition was nothing short of mapping the entire oikoumene (inhabited world). Using latitude and longitude coordinates, he plotted locations from the British Isles to Southeast Asia—though with gaps and distortions due to limited traveler accounts and instrumental precision.

Key Features of Geographia

1. Coordinate System: Ptolemy’s grid of latitudes and longitudes was revolutionary, though his prime meridian (passing through the Canary Islands) and exaggerated landmass sizes (e.g., Sri Lanka) led to errors.

2. Projection Techniques: He proposed methods to represent the spherical Earth on flat maps, foreshadowing modern cartography. Unfortunately, his underestimation of Earth’s circumference (based on Posidonius’ flawed calculations) persisted for centuries.

The Silk Road and Beyond

Ptolemy’s references to the Silk Road and lands east of Persia reveal the limits of Greco-Roman geographical knowledge. His “Serica” (China) and “Sinae” (unknown eastern regions) were vague, yet his work tantalized Renaissance explorers seeking routes to Asia.

Ptolemaic Astrology in Depth

The Tetrabiblos positioned astrology as a “science” of probabilistic influences rather than absolute fate. Ptolemy argued that celestial configurations affected tides, weather, and national destinies—aligning with Aristotle’s notion of celestial “sublunar” influences.

The Four Elements and Zodiac

Ptolemy correlated planetary positions with the four classical elements (fire, earth, air, water) and zodiac signs. For example:

- Saturn governed cold and melancholy (earth/water).

- Mars ruled heat and aggression (fire).

His system became standard in medieval and Renaissance astrology, despite criticism from skeptics like Cicero.

Medieval Europe: Ptolemy’s Renaissance

After centuries of neglect in Europe (where much Greek science was lost), Ptolemy’s works re-entered Latin scholarship via Arabic translations in the 12th century. The Almagest became a university staple, and geocentric cosmology was enshrined in Catholic doctrine—partly thanks to theologians like Thomas Aquinas, who reconciled Ptolemy with Christian theology.

Challenges from Within

Even before Copernicus, cracks appeared in the Ptolemaic system. The Alfonsine Tables (13th century), based on Ptolemy, revealed inaccuracies in planetary positions. Astronomers like Peurbach and Regiomontanus attempted revisions, but the model’s complexity grew untenable.

Conclusion (Part 2)

Ptolemy’s legacy is a paradox: his models were both brilliant and fundamentally flawed, yet they propelled scientific inquiry forward. Islamic scholars refined his astronomy, while European explorers grappled with his geography. In the next installment, we’ll explore how the Copernican Revolution dismantled Ptolemy’s cosmos—and why his influence persisted long after heliocentrism’s triumph.

The Copernican Revolution: Challenging Ptolemy’s Universe

When Nicolaus Copernicus published De revolutionibus orbium coelestium in 1543, he initiated one of history's most profound scientific revolutions. His heliocentric model didn't just rearrange the cosmos - it fundamentally challenged the Ptolemaic system that had dominated Western astronomy for nearly 1,400 years. Yet interestingly, Copernicus himself remained deeply indebted to Ptolemy's methods, retaining epicycles (though fewer) and uniform circular motion in his own calculations.

Why Ptolemy Couldn't Be Ignored

The transition from geocentrism to heliocentrism wasn't simply about Earth's position but represented a complete rethinking of celestial mechanics. However:

- Copernicus still needed Ptolemy's mathematical framework to make his model work

- Many of the same observational data (often Ptolemy's own) were used

- The initial heliocentric models were no more accurate than Ptolemy's at predicting planetary positions

Tycho Brahe's Compromise

The Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) proposed an intriguing geo-heliocentric hybrid that:

1. Kept Earth stationary at the center

2. Had other planets orbit the Sun

3. Used Ptolemaic-level precision in measurements

This system gained temporary favor as it avoided conflict with Scripture while incorporating Copernican elements.

Galileo's Telescope: The Final Blow

Galileo Galilei's celestial observations in 1609-1610 provided the smoking gun against Ptolemaic cosmology:

- Jupiter's moons proved not everything orbited Earth

- Venus' phases matched Copernican predictions

- Lunar mountains contradicted perfect celestial spheres

The Church's Dilemma

While Galileo's discoveries supported heliocentrism, the Catholic Church had formally adopted Ptolemy's system as doctrinal truth after Aquinas' synthesis. This led to:

- The 1616 condemnation of Copernicanism

- Galileo's famous trial in 1633

It would take until 1822 for the Church to accept heliocentrism officially.

Kepler's Breakthrough: Beyond Ptolemy's Circles

Johannes Kepler's laws of planetary motion (1609-1619) finally explained celestial mechanics without Ptolemy's complex devices:

1. Elliptical orbits replaced epicycles

2. Planets sweep equal areas in equal times

3. The period-distance relationship provided physical explanations

Remarkably, Kepler initially tried to preserve circular motion, showing how deeply rooted Ptolemy's influence remained in astronomical thought.

Legacy in the Enlightenment and Beyond

Even after being scientifically superseded, Ptolemy's work continued to influence scholarship:

- Isaac Newton studied the Almagest

- 18th-century astronomers referenced his star catalog

- Modern historians still analyze his observational techniques

The Ptolemaic Revival in Scholarship

Recent scholarship has reassessed Ptolemy's contributions more fairly:

- Recognizing his observational accuracy given limited instruments

- Appreciating his mathematical ingenuity

- Understanding his role in preserving ancient knowledge

Ptolemy's Enduring Influence on Geography

While Ptolemy's astronomical models were replaced, his geographical framework proved more durable:

- The latitude/longitude system remains fundamental

- His map projections influenced Renaissance cartography

- Modern digital mapping owes conceptual debts to his coordinate system

Rediscovery of the Geographia

The 15th-century rediscovery of Ptolemy's Geographia had immediate impacts:

- Printed editions with maps influenced Christopher Columbus

- Inspired new exploration of Africa and Asia

- Standardized place names across Europe

Ptolemy in Modern Science and Culture

Ptolemy's name and concepts persist in surprising ways:

- The Ptolemaic system appears in planetariums as an educational tool

- "Ptolemaic" describes any outdated but once-dominant paradigm

- Features on the Moon and Mars bear his name

Historical Lessons from Ptolemy's Story

Ptolemy's legacy offers valuable insights about scientific progress:

1. Even "wrong" theories can drive knowledge forward

2. Scientific revolutions don't happen in jumps but through cumulative steps

3. Methodology often outlasts specific conclusions

Conclusion: The Timeless Scholar

Claudius Ptolemy represents both the power and limits of human understanding. For over a millennium, his vision of an Earth-centered cosmos organized the way civilizations saw their place in the universe. While modern science has proven his astronomical models incorrect, we must recognize:

- His work preserved crucial knowledge through the Dark Ages

- His methods laid foundations for the Scientific Revolution

- His geographical system transformed how we conceive space

The very fact that we still study Ptolemy today - not just as historical curiosity but as a milestone in human thought - testifies to his unique position in the story of science. In an age of satellites and space telescopes, we stand on the shoulders of this Alexandrian giant who first sought to map both the earth and heavens with mathematical precision. His legacy reminds us that scientific truth is always evolving, and that today's certainties may become tomorrow's historical footnotes.

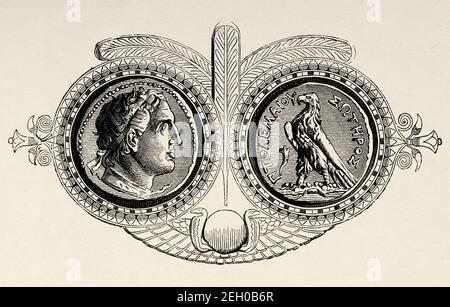

Ptolemy I Soter: The Rise of a Macedonian Pharaoh

In the pages of history, few figures have successfully transitioned from the chaos of conquest to the consolidation of a grand dynasty. Ptolemy I Soter, a key player in the epochal upheaval following Alexander the Great's reign, not only wove his name into the annals of history but also established the groundwork for a dynasty that endured for nearly three centuries. This Macedonian general, turned self-proclaimed king, deftly navigated the turbulent waters of post-Alexandrian society, establishing a legacy that has resonated through millennia.

The Early Years and Rise to Power

Born circa 367 BCE, Ptolemy's early life unfolded amid the pinnacle of Macedonian ambition. He was a close companion of Alexander the Great, nurtured in the traditions of classical Hellenistic education and military prowess. Ptolemy’s roots were steeped in nobility, with some accounts suggesting he may have had familial links to Alexander himself, possibly through his mother Arsinoe, hinting at a complex web of dynastic allegiances.

As a trusted general and confidante of Alexander, Ptolemy's prowess was evident in various military campaigns. From the searing sands of Egypt to the mountains of India, Ptolemy's loyalty to Alexander never waned. Upon Alexander's untimely death in 323 BCE, the sprawling empire was left in a precarious balance, with satraps and generals vying for control over fragments of the vast dominion.

The Satrap of Egypt: Initiating Rule

In the chaotic partitioning of Alexander's empire, Ptolemy was appointed satrap of Egypt, a strategically significant and wealthy province. His governance commenced amid a maelstrom of political maneuvering and alliance-building, necessitating astute judgment and strategic foresight. Ptolemy seized his opportunity with decisive actions, notably securing Alexander's body, a revered symbol of legitimate rule, and bringing it to Memphis—this act alone solidified his authority in the eyes of both the Macedonians and the Egyptians.

Ptolemy's tenure as satrap soon witnessed the intricacies of regional power dynamics. He recognized the immense potential afforded by Egyptian resources, particularly the fertile lands of the Nile. Ptolemy embarked on substantial infrastructure projects aiming to rejuvenate agriculture, restore stability, and invigorate economic prosperity. Such initiatives were pivotal not only in securing domestic peace but also in establishing Egypt as a pivotal force capable of independent assertion in the Hellenistic world.

From Satrap to King: The Birth of the Ptolemaic Kingdom

Ptolemy’s astute administrative skills combined with military might gradually steered him from a satrap's modest authority towards the regal ambition of a kingdom. By 305 BCE, Ptolemy declared himself Pharaoh, marking the inception of the Ptolemaic Kingdom. This bold move echoed a meticulous blend of Macedonian and Egyptian traditions, aligning strategically with native customs to secure local support. The adoption of pharaonic iconography, rituals, and temple sponsorships underscored Ptolemy’s adept management of cultural integration, making him a ruler not just by force, but by acceptance as well.

The newly minted Pharaoh effectively centralized his power, maneuvering deftly amid the engagements and alliances that ensued as other Diadochi (successor) rulers rose and fell across the fragmented empire. Ptolemy's strategic insight was evident in consolidating control over essential territories bordering Egypt, including Cyprus and parts of modern-day Libya, thereby buttressing his nascent kingdom against potential threats.

The establishment of Ptolemaic rule also heralded a golden age of cultural flourishing and scientific advancement under Ptolemy I’s patronage. Alexandria, the kingdom's pulsating heart, burgeoned into a formidable center of learning and cross-cultural dynamism, home to scholars, poets, and philosophers whose works would resonate long beyond Greece's borders. Through the patronage of the storied Library of Alexandria, Ptolemy laid the intellectual foundation for an enduring legacy of knowledge and inquiry.

In conclusion, Ptolemy I Soter's rise from a Macedonian general to the sovereign of Egypt echoes the transformational turbulence of his era: a testament to the interplay of ambition, cultural adaptation, and dynastic vision. As the founder of a lasting dynasty in Egypt, Ptolemy’s legacy is interwoven with the very fabric of ancient and subsequent cultures, rendering him a monumental figure in both Egyptian and Hellenistic history.

The Consolidation of Power and Cultural Patronage

Once Ptolemy I Soter secured his position as Pharaoh, he embarked on the significant task of consolidating his rule, both domestically and on the broader Hellenistic stage. His reign wasn't merely about asserting dominance through military conquest or political stratagems; it was also characterized by an intellectual and cultural renaissance that left an indelible mark on the ancient world.

Ptolemy's leadership was marked by a conscious effort to harmonize Greek and Egyptian cultures. He skillfully incorporated Egyptian religious customs into his court, taking on traditional titles such as "Soter," meaning "Savior," which resonated deeply with his subjects. By blending Greek and Egyptian traditions, Ptolemy fostered a sense of unity in a culturally diverse population. This syncretic approach was instrumental in crafting an enduring identity for his nascent empire, one that survived long after his tenure.

The Architectural and Scientific Landmarks of Ptolemy's Egypt

Under Ptolemy's reign, Alexandria rose to become a beacon of architectural splendor and intellectual achievement. The city itself was a masterstroke of urban planning, featuring Halicarnassian architect Dinocrates' vision that conveyed both grandeur and cultural sophistication. The construction of the Pharos of Alexandria, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, was initiated in his time and became a symbol of maritime prowess and engineering excellence.

More than just grand edifices, the heart of Alexandria pulsed with vibrant intellectual life. At its core was the Library of Alexandria, arguably the most ambitious and significant repository of knowledge in the ancient world. Ptolemy’s vision for this institution was grandiose—not just as a collection of texts but as a hub of intellectual exchange. Scholars, mathematicians, poets, and scientists flocked to Alexandria, drawn by the promise of patronage and the city’s cosmopolitan allure.

Ptolemy, himself a man of learning, encouraged these intellectuals by championing the translation of important texts and the development of diverse fields of study. The Ptolemaic era birthed advancements in astronomy, mathematics, and medicine. Notably, Ptolemy's patronage extended to individuals such as Euclid, whose "Elements" laid the groundwork for modern geometric theory, and Eratosthenes, who remarkably calculated the circumference of the Earth with surprising accuracy.

Navigating the Perils of the Diadochi Wars

Even as he fostered cultural and scientific achievements, Ptolemy Soter was deeply embroiled in the Diadochi Wars, the series of conflicts among Alexander’s former generals over control of the empire. His military acumen was frequently tested as alliances shifted and conflicts erupted across the Mediterranean basin. The strategic necessity of maintaining a strong military presence was evident in his careful selection of capable generals and the fortification of Egypt's borders.

Ptolemy's political and military strategy was characterized by careful diplomacy and selective engagement in warfare. This mastery of statecraft allowed him to extend influence while avoiding the pitfall of overextension that plagued many of his contemporaries. His diplomatic maneuvers often involved strategic marriages and alliances that fortified his position within the complex power structure of the post-Alexandrian world.

Ptolemy’s success in these endeavors did not only rest on military might but also on his acute understanding of propaganda and legitimacy. By commissioning art and coinage that depicted him favorably, often in the company of Alexander the Great, he bolstered his image both at home and abroad. Such portrayals reinforced his narrative as a rightful successor to Alexander’s legacy, aligning himself as a champion of Greek culture within his Egyptian dominion.

The Legacy of Ptolemy I Soter

Ptolemy I Soter’s reign set the foundations for a dynasty that would last until the Roman annexation of Egypt in 30 BCE. His strategies of cultural integration and political resilience laid the groundwork for a period of prosperity and unity within the diverse geographic and ethnic landscape of ancient Egypt. The Ptolemaic Kingdom transformed Egypt into a powerful and influential state, exerting a profound influence throughout the Hellenistic world.

Yet, his legacy is not without its complexities. While Ptolemy adeptly fostered a golden era of cultural and scientific achievement, the Ptolemaic dynasty faced challenges of lineage disputes and succession crises. These troubles often stemmed from the complex web of familial alliances and intermarriages that were both tools of political strategy and sources of internal strife. Nevertheless, the durability of the dynasty, initiated by Ptolemy, speaks to the solid base of power and culture he effectively instituted.

In contemplating the legacy of Ptolemy I Soter, historians find a compelling narrative of a ruler who balanced martial prowess with visionary leadership. The synthesis of Greek and Egyptian elements under his rule not only stabilized his kingdom but also enriched both cultures, creating a unique symbiosis that continued to evolve long after his death. As a general-turned-king, Ptolemy's life's work was a testament to the transformative potential of visionary leadership in an era of unprecedented change.

The Challenges of Succession and Dynasty

While Ptolemy I Soter's reign laid a robust foundation for Egypt's Hellenistic age, the challenge of securing his dynasty's future loomed large. As with many ruling families, the issue of succession was fraught with peril and potential for internecine conflict. To ensure a smooth transition, Ptolemy engaged in meticulous planning to ensure the continuity of his lineage and the kingdom’s stability.

In an astute political maneuver, Ptolemy abdicated in 285 BCE in favor of his son, Ptolemy II Philadelphus, thereby pre-empting the often uncontrollable chaos that followed a ruler's death. Ptolemy I’s decision to relinquish power while still alive was a calculated risk, reflective of his sophisticated understanding of governance and legacy. This action mitigated potential struggles over succession, allowing for a relatively peaceful transition of power and setting a precedent for future rulers.

Ptolemy II's ascension to the throne was accompanied by the continuation of his father's policies. His reign further strengthened the cultural and economic infrastructure established by Ptolemy I, maintaining Egypt's status as a beacon of Hellenistic brilliance. Despite occasional familial discord, the Ptolemaic dynasty sustained through the strategic marriages and alliances designed to fortify its dominion across the volatile Mediterranean landscape.

Ptolemy’s Influence on Religion and Integration

Religiously, Ptolemy I Soter's reign marked a significant integration of Greek and Egyptian pantheons. Recognizing the importance of religious unity in a multicultural society, Ptolemy promoted the worship of the syncretic deity Serapis, blending elements of Greek and Egyptian religious beliefs. Serapis became a unifying figure, worshipped across Egypt and by Hellenistic diasporas, effectively bridging cultural divides.

This religious fusion was both a pragmatic political strategy and a genuine reflection of Ptolemy's vision of a cohesive society. The Serapeum, a temple dedicated to Serapis, became a focal point of worship and theological study, further cementing Alexandria’s status as a spiritual as well as intellectual epicenter. The coexistence of Egyptian deities with Greek gods under Ptolemaic rule exemplified a model of cultural integration that preempted the complexities of global multiculturalism centuries later.

Furthermore, Ptolemy's encouragement of coexistence fostered not just peace, but a vibrant cultural tapestry that manifested in the arts and sciences. The Ptolemaic approach to governance not only fortified their power but emboldened Egyptian identity within the global dialogue fostered by Hellenistic culture—a dialogue that fed into the rich historical and cultural legacies witnessed today.

The Enduring Legacy of Ptolemy I Soter

Ptolemy I Soter's legacy is intricately woven into the narrative of both Hellenistic and ancient Egyptian history. His transformation of Egypt into a pivotal Hellenistic state set a precedent not only for subsequent rulers of Egypt but for the concept of governance through cultural symbiosis. Under his guidance, Egypt became a center of intellectual magnificence and economic prosperity.

The dynasty’s endurance—culminating nearly three centuries with Cleopatra VII’s famous rule before succumbing to Roman annexation—speaks volumes of the groundwork Ptolemy laid. The Ptolemaic dynasty’s prominence in history owes much to its ability to blend Greek innovation and Egyptian tradition, yielding a unique cultural and political entity that has fascinated scholars and historians through the ages.

Historians frequently cite Ptolemy I’s pragmatic leadership style, strategic marriages, and cultural policies as cornerstones of his successful reign. These elements contributed not only to his family's hold on power but also to the shaping of a dynamic society enriched by cultural cross-fertilization. His success outlined a blueprint of governance that embraced diversity, a concept increasingly relevant in today’s multifaceted global landscape.

Ptolemy I's impact reaches beyond his political achievements to an enduring symbolic legacy caught between myth and history. As both a savior and a founder, his efforts remind us of the potential of visionary leadership to craft societies that balance the chaos of innovation with the stability of tradition—a balancing act as relevant today as it was nearly two and a half millennia ago.

In reflecting on Ptolemy I Soter's life and legacy, we observe the timeless influence of a leader who harnessed the lessons of the past to forge a new path for the future. His mastery in the art of governance was not merely in wielding power but in understanding the profound impact of culture as a unifying force. As history turns its gaze to newer epochs, the story of Ptolemy I Soter remains a testament to the enduring power of visionary rule in shaping the cultural, intellectual, and political landscapes of civilization.

Ptolemy III Euergetes: The Philhellene Pharaoh of Egypt

The sands of time have all but buried the echoes of ancient Egypt, yet every so often a figure emerges whose actions reverberate through history, leaving an indelible mark on human civilization. Ptolemy III Euergetes, the third ruler of Egypt's Ptolemaic Dynasty, was one such figure. His reign, from 246 to 222 BCE, stands as one of the most prosperous and influential periods in the ancient world, marked by military conquests, cultural patronage, and economic prosperity.

Ascension to the Throne

Ptolemy III was born around 284 BCE to Ptolemy II Philadelphus and Arsinoe I. As the grandson of Ptolemy I Soter, a trusted general of Alexander the Great and the founder of the Ptolemaic Dynasty, his lineage was venerable and steeped in the illustrious traditions of both Macedonian heritage and Egyptian rulership. Upon the death of his father, Ptolemy II, in 246 BCE, Ptolemy III ascended the throne and swiftly set about asserting his dominion across the Mediterranean world.

His early years as pharaoh were marked by solidifying alliances and enhancing Egypt's international stature. A key alliance was secured through his marriage to Berenice II, daughter of Magas of Cyrene, thereby uniting two powerful realms and quelling potential rivalries. This alliance also brought Cyrenaica, a coastal region of modern-day Libya, under Egyptian influence, thereby expanding Ptolemy III's domain and securing a critical foothold in North Africa.

The Third Syrian War (246–241 BCE)

Ptolemy III's reign is perhaps best remembered for the Third Syrian War, also known as the Laodicean War, a conflict that underscored his military acumen and strategic prowess. Upon his accession, rumors swirled of turmoil within the Seleucid Empire, Egypt's great rival to the east. Antiochus II, the Seleucid King and brother-in-law to Ptolemy III's sister, Berenice Syra, had died. His death sparked a succession crisis, with Antiochus's two wives, Berenice and Laodice, each vying for their sons' claim to the throne.

Ptolemy III embarked on a military campaign to support his sister Berenice's claim and ensure Egyptian dominance in the region. His forces swept through Syria and into Babylonia, capturing vast territories and winning decisive victories that solidified Egypt's influence. The campaign, however, was marred by personal tragedy; Berenice and her son were murdered in Antioch, preventing a complete Ptolemaic hegemony over the Seleucid realm. Despite this, Ptolemy III's successes were substantial, expanding Egypt's influence as far as the Tigris and laying the groundwork for future stability and prosperity.

Cultural Patronage and Economic Prosperity

Ptolemy III's reign was marked by an invigorated cultural and scientific pursuit that enriched Egypt and left a lasting legacy on the intellectual landscape of the ancient world. He was a staunch supporter of the Mouseion of Alexandria, a research and learning institution that housed the famed Library of Alexandria. As a patron of the arts and sciences, Ptolemy III attracted scholars, poets, and artists from across the Hellenistic world, fostering an ethos of cultural synthesis that was emblematic of the period.

The economic prosperity during his reign was palpable. The wealth generated from new conquests, combined with a concerted investment in agriculture, infrastructure, and trade routes, energized Egypt's economy. Ptolemy III implemented policies to enhance agricultural productivity, employing irrigation projects that maximized the fertile Nile Valley's potential and reviving trade networks that extended into Africa, Asia, and the Mediterranean Basin. This economic vibrancy not only buttressed the kingdom's prosperity but also supported his ambitions for cultural and scientific advancement.

Ptolemy III's Legacy

Ptolemy III Euergetes, whose name translates to "Benefactor," was the epitome of a Hellenistic ruler—a charismatic blend of warrior and patron, conqueror and philosopher-king. His reign was characterized by expansionary zeal balanced with a profound commitment to the arts and sciences. Through a combination of military success, economic astuteness, and cultural patronage, he reinforced Egypt’s position as a beacon of Hellenistic civilization. Though his life was cut short in 222 BCE, the aftershocks of his reforms and policies rippled through time, impacting the ancient world in ways that resonate even today.

As we conclude this first segment of our exploration into the life and legacy of Ptolemy III, we set the stage for further inquiry into his multifaceted rule. In the following sections, we will delve deeper into his familial alliances, ongoing foreign policy endeavors, and the domestic reforms that underpinned his revolutionary reign.

A Familial Power Web: Alliances and Rivalries

One of the cornerstones of Ptolemy III Euergetes's reign was his adeptness at navigating the intricate web of familial alliances and rivalries that characterized the Hellenistic world. These alliances were crucial for maintaining power and expanding influence across territories, often determining the outcomes of political and military endeavors.

Ptolemy III’s marriage to Berenice II was not only a unification of two potent dynasties, but also a strategic consolidation of power that served as a bulwark against adversaries. Berenice was no passive consort; she was an influential figure who wielded considerable sway, both in political matters and in sponsoring cultural activities. Their union was emblematic of the era’s power marriages that sought to combine resources, lands, and political strength to create formidable ruling blocs.

The family dynamics took dramatic turns with the involvement of Ptolemy III’s sister, Berenice Syra, in the contentious succession of the Seleucid throne. This familial connection ignited the flames of the Third Syrian War, illustrating the dual-edged nature of kin alliances—capable of both bolstering power and sparking conflict. Ptolemy III’s intervention in favor of his sister demonstrated a deft balancing act between family loyalty and political strategy, though it equally highlighted the potential volatility of such entanglements.

Diplomatic Maneuvering in the Hellenistic World

While Ptolemy III's military campaigns extended Egypt's borders and assertively projected its power, his diplomatic endeavors played an equally crucial role in maintaining the kingdom’s robust position in the Hellenistic world. He skillfully navigated relationships with the other major Hellenistic states, including Macedonia, the Seleucid Empire, and several city-states across Greece and Asia Minor.

Ptolemy III's foreign policy was marked by a mix of assertive action and cautious diplomacy. Recognizing the strategic importance of sea power, he bolstered Egypt's naval capabilities to protect maritime trade routes and ensure Egypt's influence in the Eastern Mediterranean. His efforts were rewarded with control over key ports and islands, thus securing economic avenues vital for Egypt's prosperity.

Moreover, Ptolemy III astutely engaged in diplomatic marriages and alliances. His foreign policies were not solely aimed at territorial expansion but also at creating a network of alliances that could counterbalance the power of his rivals. This approach allowed him to maintain Egypt's independence from the formidable Seleucid and Macedonian forces, often positioning Egypt as a peacemaker and arbiter in broader geopolitical disputes.

Domestic Reforms: A New Vision for Egypt

On the home front, Ptolemy III was a visionary leader who implemented numerous reforms to strengthen Egypt's domestic framework and enhance the livelihoods of its people. Under his rule, Egypt's administration was characterized by increased efficiency and centralization, which helped streamline governance in one of the ancient world's most powerful states.

Ptolemy III was known for prioritizing agricultural advancements, crucial for a nation so heavily reliant on the fertility of its lands. His reforms supported irrigation systems and agricultural experimentation that maximized the Nile’s bounties, thereby safeguarding food supplies against the perils of droughts or floods. These initiatives not only fortified Egypt's food security but also provided surpluses that could be traded with neighboring regions, enhancing Egypt's wealth.

Additionally, Ptolemy III invested in public infrastructure, including the construction of temples and other civic projects that reinforced the cultural and religious integration of Greek and Egyptian traditions. This investment in monumental architecture served dual purposes: it symbolized the pharaoh's divine mandate and cemented his prestige and legacy, while simultaneously improving the urban landscape to the benefit of the populace.

The legal and administrative changes under his reign fostered a more cohesive society where trade flourished. His policies encouraged the integration of Egyptian and Greek customs, creating a hybrid culture that was inclusive yet distinct. Such reforms made Egypt not only a land of wealth but also a hub of intellectual and cultural exchange, drawing scholars and traders alike from distant lands.

The Impact on Hellenistic Culture and Beyond

The influence of Ptolemy III Euergetes transcended his military victories and domestic policies. During his reign, Egypt became a crucible for Hellenistic culture, a melting pot where Greek and Egyptian beliefs, practices, and innovations intermingled. This era of cultural synthesis fostered a unique identity that influenced subsequent generations and left a lasting legacy on the broader Mediterranean and Near Eastern regions.

His support of the arts, sciences, and philosophy was instrumental in sustaining Alexandria as the intellectual epicenter of the ancient world. The enlightenments nurtured during Ptolemy III's reign charted new courses in astronomy, mathematics, and philosophy, many of which would later inform the Roman and Byzantine scholars and beyond into the Islamic Golden Age and our modern comprehension of the ancient world.

As we advance in examining the tenure of Ptolemy III Euergetes, it becomes evident that his impact extended well beyond conventional kingship. In the next part of this article, we will delve more deeply into the long-term consequences of his policies, scrutinize notable figures influenced by his reign, and explore the spiritual and religious transformations that he shepherded during his leadership in ancient Egypt.

Religious Syncretism and Spiritual Evolution

Ptolemy III Euergetes’s reign was remarkable not only for political and cultural advancements but also for encouraging a unique religious syncretism. The Ptolemaic dynasty was notable for its fusion of Greek and Egyptian religious practices, which allowed for integration between the Macedonian rulers and their Egyptian subjects. Ptolemy III's policies embodied this ethos, fostering spiritual harmony by synthesizing the pantheons and rituals of two influential civilizations.

A notable aspect of Ptolemy III's religious approach was his active role in temple construction and renovation, particularly notable in sanctuaries dedicated to gods venerated by both cultures, such as the temple of Horus at Edfu. In honoring Egyptian deities, Ptolemy III reaffirmed his role as a legitimate pharaoh in the eyes of native subjects, an act crucial for maintaining stability and loyalty within his realm.

His patronage extended to integrating Greek practices, exemplified by the spread of the cult of Serapis, a deity combining aspects of Osiris and Apis with Hellenistic traditions. This syncretic religion appealed to both Greeks and Egyptians, which facilitated a shared cultural identity and reduced potential for religious discord. Ptolemy III’s contributions laid lasting foundations for a spiritual synthesis that would evolve throughout the Hellenistic period.

Intellectual Flourishing in Alexandria

Under Ptolemy III, Alexandria solidified its position as a beacon of knowledge and philosophical exploration. The Great Library of Alexandria, a marvel of the ancient world, flourished with royal patronage, drawing the brightest minds of the time. The library was not merely a repository of texts but an active research institution that fostered groundbreaking innovations and cross-cultural exchanges.

Prominent scholars and mathematicians, such as Archimedes and Eratosthenes, were linked to the intellectual circles of Alexandria during or after Ptolemy III's reign. Eratosthenes, who would become the chief librarian of Alexandria, made remarkable strides in geography and astronomy, famously calculating the Earth's circumference with remarkable accuracy. Such intellectual endeavors underscored the city's status as a hub of learning, fueled by Ptolemy III's commitment to scholarly advancements.

The promotion of learning also extended to the development of a scientific temper and critical inquiry, which permeated Mediterranean society and laid groundwork for future intellectual achievements. By nurturing academic institutions and promoting the free exchange of ideas, Ptolemy III ensured that his reign left a lasting intellectual legacy that would inspire generations to follow.

Enduring Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Ptolemy III Euergetes, a paragon of Hellenistic leadership, has been cast by historians as a ruler whose reign encapsulated the zenith of the Ptolemaic dynasty’s power and cultural impact. His contributions went far beyond territorial expansions, establishing frameworks that spurred economic growth, cultural prosperity, and religious unity across a diverse empire.

Despite the glory of his reign, the subsequent years saw challenges that gradually eroded the foundations he set. Subsequent Ptolemaic rulers, facing both internal unrest and external pressures, struggled to maintain the same degree of prestige. Nevertheless, the systems that Ptolemy III put into place continued to influence governance, culture, and religion even amid subsequent political vicissitudes.

The evaluation of Ptolemy III’s legacy offers essential insights into the dynamics of ruling a multicultural empire. His ability to blend conquest with cultural patronage, grounded in religious and intellectual synergy, highlights a balance between strength and wisdom that is rare in historical analysis. His reign remains a testament to the potential of inclusive governance and the enduring power of cultural and intellectual dialogue.

The reverberations of his leadership stretch beyond the scope of time, knitting an intricate tapestry of human achievement where the fusion of ideas and identities created something remarkable and enduring. Thus, the story of Ptolemy III Euergetes is far more than a chapter of ancient rule; it is a narrative that offers timeless lessons in diplomacy, governance, and the shared journey of human civilization through the ages.

Ptolemy IV Philopator: The Reign of a Controversial Egyptian Pharaoh

Ptolemy IV Philopator: The Reign of a Controversial Egyptian Pharaoh

Ptolemy IV Philopator, who ruled Egypt from 221 to 204 BCE, marks one of the most contentious and complex periods in the history of the Ptolemaic Dynasty. His reign is characterized by both internal decadence and external challenges that underlined the weaknesses within the Ptolemaic Kingdom—a state powerful in breadth yet fractious in its internal machinations.

The Early Life and Ascension to the Throne

Born in 244 BCE in Alexandria, Ptolemy IV was the son of Ptolemy III Euergetes and Berenice II. His early life in the Egyptian court was shaped by the tides of royal intrigue and the complex web of familial relations that defined the Hellenistic period. When Ptolemy IV ascended to the throne following the death of his father, he inherited a powerful empire that stretched from Libya to the far reaches of Cyprus and parts of the Aegean Sea.

However, the transition of power was not entirely smooth. The ascendancy of Ptolemy IV was marred by a series of court conspiracies, most notably the murder of his mother, Berenice II, an act reportedly orchestrated by his powerful advisor, Sosibius. This tumult set a tone for Ptolemy’s reign, highlighting the challenges of maintaining loyalty among court officials and influence over regional governors.

The Battle of Raphia: Conflict with Antiochus III

One of the critical events during the reign of Ptolemy IV was the Battle of Raphia in 217 BCE, where his forces clashed with the armies of Antiochus III of the Seleucid Empire. This battle was not just a fight over territories in Coele-Syria but also a broader contest of dominance between two major Hellenistic powers.

Under the leadership of his generals, including the trusted Sosibius, Ptolemy’s army, significantly composed of native Egyptian soldiers, faced off against a well-equipped Seleucid force. The battle showcased Ptolemy’s ability to rally and train a formidable army, despite his often-debated leadership qualities. In the end, Ptolemaic forces emerged victorious, securing Egypt's control over the contested territories and temporarily bolstering Ptolemy's reign.

Domestic Administration and Controversies

Ptolemy IV’s reign was marked by several domestic policies that focused on religion and culture, yet his administration often faced criticism for neglect and corruption. He is credited with constructing and sponsoring numerous religious monuments and temples, including the renowned Temple of Horus at Edfu, which stands as a testament to the grand architectural endeavors of the period.

However, his pursuits were not without criticism. Ptolemy IV’s administration became infamous for luxurious indulgence and political negligence. Historical accounts by ancient chroniclers, though sometimes colored by bias, portray him more preoccupied with the pleasures of the court than the rigors of governance. This lapse opened the doors to corruption and weakened centralized control over the expansive Ptolemaic territories.

The Decline of Royal Authority

As Ptolemy IV's reign progressed, the amplification of internal dissent and the rising influence of his court advisors led to a steady decline in royal authority. Social unrest, largely fueled by economic difficulties and increased burdens on native Egyptians—despite their contributions during crises like the Battle of Raphia—further strained relations between the ruling Greeks and native Egyptian populations.

The latter years of his rule were overshadowed by increasing domestic unrest, aggravated by Ptolemy’s failure to address growing socio-economic disparities within his kingdom. This period sowed seeds of rebellion, which would continue to ferment and ultimately weaken the governance of his successor, Ptolemy V Epiphanes.

While attempts were made to maintain facade stability, including efforts to engage with Egyptian religious traditions more directly, the societal divisions stoked by years of administrative mismanagement could not be easily reconciled.

The Role of Sosibius and Agathocles

The political sphere of Ptolemy IV's court was dominated by influential figures like Sosibius and Agathocles, whose manipulations greatly impacted the trajectory of his reign. Sosibius, in particular, was instrumental in securing Ptolemy's ascendancy by orchestrating the elimination of any perceived threats, a move that consolidated his power behind the throne.

Agathocles, equally ambitious and wily, connived his way into the royal family's trust, earning high-ranking positions within the government. Together, their governance style was characterized by intrigue and a focus on self-aggrandizement over the kingdom's welfare. Their influence was pervasive; they employed cunning tactics, often resorting to political purges and opaque dealings to maintain their sway over the king and the broader kingdom.

This reliance on powerful advisors was a double-edged sword. While it allowed Ptolemy IV to navigate initial challenges, it also put him at the mercy of their ambitions, often at the expense of competent governance. The deep-seated reliance on these advisors weakened the traditional executive control emanating from the Pharaoh, leading to decentralized power that often spiraled into chaos.

Cultural Contributions and Greek Influence

Under Ptolemy IV's rule, the cultural landscape of Egypt was richly infused with Greek traditions, reflecting the broader Hellenistic influence that was prevalent across the territories. Alexandria, the Ptolemaic capital, became a beacon of Hellenic culture, drawing scholars, artists, and philosophers from across the Mediterranean world.

The famed Library of Alexandria continued its tradition of scholarship, acting as a central repository of human knowledge and an anchor for cultural achievements. Despite his apparent detachment from the day-to-day governance, Ptolemy IV showed a keen interest in the arts and sciences. This patronage allowed for the flourishing of literature, poetry, and scientific inquiry, ensuring that Alexandria remained the intellectual heart of the Hellenistic world.

However, this cultural zenith also highlighted the disparities within Egyptian society. The emphasis on Greek forms and functions often overshadowed native Egyptian traditions, causing subtle tensions which would later manifest in more pronounced societal divides. The hybridization of cultures, while beneficial to art and philosophy, inadvertently sowed seeds of identity conflicts among the native populace.

Religious Policy and Legacy

Ptolemy IV's reign was also marked by his initiatives in the religious domain, which sought to consolidate his rule and earn the favor of the Egyptian populace. His dedication to constructing temples and monuments exemplified a strategy to appease the native Egyptian deities, an endeavor underpinned by political pragmatism.

He promoted the integration of Greek and Egyptian religions, a move designed to bridge the cultural gaps between the ruling elite and the indigenous people. This syncretic approach found its embodiment in the worship of Serapis, a deity unifying Hellenistic and native Egyptian religious elements, and promoted in both iconography and cult practices.

Despite these efforts, Ptolemy IV's religious policies were perceived as attempts to legitimate his rule rather than genuine spiritual commitment, leaving his legacy in this sphere contested and complex.

The Death and Succession of Ptolemy IV

The end of Ptolemy IV's reign came with both personal and political turmoil. His health and the quality of his rule declined, contributing to increasing destabilization within Egypt. His death in 204 BCE opened a power vacuum that his advisors, Sosibius and Agathocles, sought to fill by orchestrating the ascension of his infant son, Ptolemy V Epiphanes.

The transition of power was fraught with intrigue and chaos. Agathocles' regency for the young Ptolemy V was marked by unrest and uprisings, a testament to the simmering discontent leftover from his predecessor's rule. Notably, the events that transpired immediately after Ptolemy IV's death showcased the brittle nature of dynastic successions clouded by ambition and treachery.

Ptolemy IV’s Enduring Impact

In historical retrospection, Ptolemy IV Philopator’s reign is frequently viewed through a prism of decline, one that charts the gradual erosion of centralized authority that would continue to affect his successors. Despite his contributions to culture and religion, his era is often overshadowed by reports of opulence and political neglect, characteristics that are extensively recorded by historians such as Polybius and others.

Yet, the defining legacy of his reign stretches beyond individual assessment, serving as a reflection of broader socio-political dynamics during the Hellenistic period. It underscores the challenges of balancing diverse cultural traditions, the perils of administrative complacency, and the fragile nature of power sustained by delegation.

Ptolemy IV Philopator’s time as Egyptian pharaoh stands as a complex tapestry interwoven with elements of cultural brilliance and political frailty—an era of opportune triumphs and eventual destabilizations that charted the course for subsequent rulers in navigating an increasingly fragmented Ptolemaic realm.