Charles Hard Townes: Pioneering Innovator and Nobel Laureate

Early Life and Education

Charles Hard Townes was born on January 28, 1915, in Greenville, South Carolina. He showed a natural aptitude for mathematics and physics from an early age, which laid the foundation for his future career as one of the most influential scientists of the 20th century. His father, Charles William Townes, was a teacher of history and literature, while his mother, Louise Townes, passed away when Chuck was only seven years old. This loss significantly shaped his personality and contributed to his independence.

Townes received his undergraduate degree from Furman University in 1935, where he excelled academically and was initiated into Phi Beta Kappa. Following this, he moved to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for his graduate studies, earning his Ph.D. in physics in 1939. His doctoral thesis focused on molecular spectra, an area that would later prove to be pivotal in his groundbreaking work.

The Rise of Quantum Electronics and Microwave Spectroscopy

Upon completing his Ph.D., Townes accepted a position at Columbia University as a research associate. It was here that he embarked on his pathbreaking research in microwave spectroscopy. His work began with a novel approach to measuring the spectral lines of molecules. By using precise measurements, Townes and his team were able to refine the accuracy of these measurements, which would be crucial for future developments in quantum electronics.

In 1945, during World War II, Townes joined the Army Signal Corps, where his expertise in spectroscopy was invaluable. There, he worked on radar systems and participated in critical wartime projects. It was during his service that Townes conceived the idea for what would become the maser (Microwave Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation), a precursor to the laser. The concept drew upon Einstein's theory of stimulated emission, which predicted that particles could be made to emit radiation at the same frequency and phase as an incoming wave, leading to amplification.

In 1946, Townes returned to Columbia University, where he further refined his ideas and began exploring practical applications of his theories. He collaborated with others, including his brother John, a mathematician, and Arthur Schawlow, a physicist and electrical engineer. Together, they worked on designs for a device that could amplify and generate light at specific wavelengths, a concept that would eventually lead to the invention of the optical laser.

The Development of the Maser and Its Impact

By 1953, Townes and his colleagues managed to build a working maser. The device utilized ammonia molecules excited by microwaves to produce coherent electromagnetic radiation at frequencies of about 24 gigahertz. This was a landmark achievement, as it was the first device capable of amplifying radiation without relying on an external light source. Townes later recalled, "The maser was like a flashlight that worked without batteries. It simply took a continuous supply of energy and turned some of the energy into light."

The development of the maser had significant implications for various fields, including astronomy and communication. Townes and his colleagues demonstrated its potential in detecting molecules in interstellar space, providing new insights into the composition and structure of distant stars and galaxies. This capability revolutionized astrophysics, enabling researchers to identify previously undiscovered chemical compounds in the universe.

Moreover, the maser laid the groundwork for the invention of the laser. The principles of the maser—specifically, stimulated emission and the mechanism of light amplification—were directly transferred to the design of lasers. Townes and Schawlow published their theoretical paper on laser in 1958, which detailed how a similar process involving visible light could achieve the same effect. Their work provided scientists with a blueprint for the construction of laser devices.

While the maser was a significant step, the true impact of Townes's work became evident with the invention of the laser. Lasers proved to be a revolutionary tool across multiple disciplines. They were employed in medical devices, precision cutting tools, telecommunications, and even consumer electronics like CD and DVD players. The versatility of lasers also contributed to technological advancements in material science, spectroscopy, and data storage.

Nobel Prize and Legacy

For his contributions to both the maser and the development of the laser, Charles Townes received numerous accolades throughout his career. In 1964, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics, shared with Nikolay Basov and Alexander Prokhorov, who conducted pioneering work on the theoretical aspects of the maser and laser. Townes's recognition came not only for the technical achievements but also for his leadership and mentorship, which inspired generations of scientists around the world.

Townes’s influence extended far beyond the scientific community. His insights into quantum mechanics and his innovative thinking played a crucial role in shaping modern technology. He believed strongly in the application of scientific knowledge for societal benefit and actively advocated for interdisciplinary collaboration between physicists, engineers, and other specialists.

Throughout his life, Townes remained deeply committed to advancing the frontiers of knowledge. His legacy is preserved through various institutions that carry forward his vision, including the National Science Foundation, where he served as the first director of the NSF Division of Engineering, and the Center for Energy Research at UC Berkeley, which bears his name.

As he reflected on his long and impactful career, Townes emphasized the importance of perseverance and imagination. "The essential ingredient for scientific progress," he often said, "is a curious mind." This simple yet profound statement encapsulates Townes's enduring legacy—a reminder that in the pursuit of scientific discovery, curiosity and creativity remain paramount.

Teaching and Mentoring: Fostering the Next Generation of Scientists

Charles Townes's contributions did not end with his groundbreaking work on the maser and laser. Throughout his career, he was committed to mentoring and teaching, nurturing the next generation of scientists. In 1961, he joined the faculty of the University of California, Berkeley, and began shaping the next generation of scientists through his teaching and mentorship.

At Berkeley, Townes established the Laboratory for Physical Biology, where he continued his research in molecular spectroscopy. His dedication to teaching and mentoring was evident in his numerous courses and lectures. He was known for his engaging teaching style, which combined rigorous scientific content with a down-to-earth approach that made complex concepts accessible to students.

Townes’s teaching at Berkeley spanned a wide range of subjects, from general physics to more specialized modules in molecular spectroscopy and quantum electronics. His approach emphasized both theoretical and practical aspects of science. He encouraged students to think critically and to question assumptions, a method that helped shape many of his students into independent thinkers and innovative researchers.

One of his most notable students was William Giauque, who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1959. Giauque, like many others, was profoundly influenced by Townes's teaching methods and his emphasis on the importance of scientific curiosity. Another prominent alumnus is Charles K. Kao, who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2009 for his pioneering work in fiber-optic communication. Kao credits Townes for fostering his interest in physics and inspiring him to pursue research that would have significant real-world applications.

Townes's impact on his students extended beyond the classroom. He mentored many in his laboratory, providing them not just with technical knowledge but also with valuable life skills. He encouraged them to explore their own interests and to be persistent in their scientific endeavors, even in the face of difficulties. This mentorship style helped to produce a generation of scientists who were not only adept at their craft but also driven by a genuine passion for discovery.

Interdisciplinary Advancements and the Role of Collaboration

Charles Townes believed strongly in the power of interdisciplinary collaboration. He understood that the boundaries between different scientific disciplines were often artificial and that breakthroughs could come when scientists from diverse backgrounds worked together. This belief was reflected in his own career, which bridged the gap between physics, biology, and engineering.

One of the most significant interdisciplinary collaborations during Townes's career was the development of the Bell Telephone Laboratories maser. This project brought together physicists, engineers, and technicians from Bell Labs, leading to the creation of the first operational maser device. The success of this collaboration highlighted the importance of such interdisciplinary efforts in advancing technology and science.

Townes often stressed the importance of communication and collaboration in the scientific community. He recognized that the rapid pace of technological advancements required scientists to be adaptable and to work across traditional boundaries. His involvement in various research projects, from molecular spectroscopy to fiber-optic communication, underscored the value of interdisciplinary approaches.

In the 1970s, Townes was among the first to advocate for the use of lasers in medical applications. He recognized the potential of lasers to deliver precise and minimally invasive treatments, a concept that would eventually lead to the development of laser surgery. The interdisciplinary nature of this work required collaboration among physicists, engineers, and doctors, illustrating the importance of such collaborations in advancing medical technologies.

Public Service and Advocacy for Science

Beyond his academic and scientific pursuits, Charles Townes was a strong advocate for public support of science. He recognized the vital role that government funding played in advancing scientific research and development. In 1958, he was appointed as the first director of the National Science Foundation (NSF) Division of Engineering. In this role, he worked to increase federal investment in engineering and technology, advocating for the importance of these fields in America’s future.

Townes's tenure at the NSF was marked by efforts to enhance public understanding of science and technology. He believed that science was not just a tool for industrial progress but also a means to address societal challenges. His advocacy for public support of science extended to various platforms, including his involvement in science policy discussions and his writings on the role of science in society.

In his later years, Townes continued to engage with the public through his writings and lectures. He authored several books and articles, making scientific concepts accessible to a broader audience. His book “The Road to Reliability: The First Fifty Years of Bell Laboratories” (1997) provided an insightful look into the history and culture of one of the world's most prestigious research institutions. By sharing his experiences and insights, Townes helped to inspire the next generation of scientists and engineers.

Recognition and Honors

Throughout his career, Charles Townes received numerous accolades for his contributions to science. In addition to the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1964, he was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1958 and served as its president from 1971 to 1973. He was awarded the National Medal of Science in 1989 and the National Medal of Technology in 1996.

These honors reflect not only Townes's scientific achievements but also his broader impact on the scientific community. His work on the maser and the laser has had a lasting legacy, influencing fields as diverse as astrophysics, telecommunications, and medicine. Moreover, his commitment to education, interdisciplinary collaboration, and public service has left a lasting imprint on the scientific world.

Legacy and Continuing Impact

Charles Hard Townes's legacy extends far beyond his pioneering work on the maser and laser. His contributions have had a lasting impact on science and technology, influencing not only the advancement of knowledge in specific fields but also encouraging broad interdisciplinary collaboration and public engagement with science. His dedication to education, mentorship, and public service has left a profound mark on the global scientific community.

In the realm of astrophysics, the maser remained instrumental in the decades following its invention. The device's ability to detect and study molecules in interstellar space contributed significantly to our understanding of the universe. Townes's work allowed astronomers to identify new molecules in distant space, expanding the catalog of materials found outside our solar system. This knowledge has been crucial in refining models of star formation, planetary evolution, and the overall composition of the cosmos.

Technological advancements owe much to Townes's innovations. The laser, which followed from the maser, has transformed countless industries. From manufacturing and surgery to communication and information storage, lasers have played a pivotal role in driving technological progress. Optical fibers, which utilize laser technology to transmit vast amounts of data over long distances, are ubiquitous in modern telecommunications networks. Moreover, the precision cutting and marking capabilities of lasers have revolutionized industries such as automotive, electronics, and aerospace.

Townes's interdisciplinary approach to science has also influenced the way modern researchers view their work. His belief in collaboration and the need to cross traditional disciplinary boundaries continues to be echoed today. Scientists increasingly recognize the value of integrating perspectives from diverse fields to tackle complex problems. This mindset has led to breakthroughs in areas such as biophotonics, where laser technology is used to study biological structures at the nanoscale, and in environmental science, where laser-based sensors provide real-time monitoring of air and water quality.

Charles Townes's legacy is not confined to specific achievements but also includes his approach to science education and his advocacy for public support of research. His emphasis on interdisciplinary collaboration and his efforts to make scientific concepts accessible to the public highlight the importance of a holistic approach to scientific advancement. By encouraging students to question and explore, and by advocating for increased public investment in science, Townes helped to build a stronger, more resilient scientific community.

In reflecting on Townes's life, it becomes clear that his innovations and teachings have far-reaching impacts. His commitment to excellence, curiosity, and collaboration continues to inspire scientists around the world. As we look to the future, Townes's lessons—about the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration, the value of public engagement, and the necessity of persistent exploration—remain as relevant today as they were during his lifetime.

Dr. Charles Townes, a true pioneer in the field of quantum electronics and a passionate advocate for science, will be remembered not only for his groundbreaking inventions but also for his profound influence on the development of modern scientific thought and practice. His legacy serves as a testament to the enduring power of scientific inquiry and the transformative potential of innovative thinking.

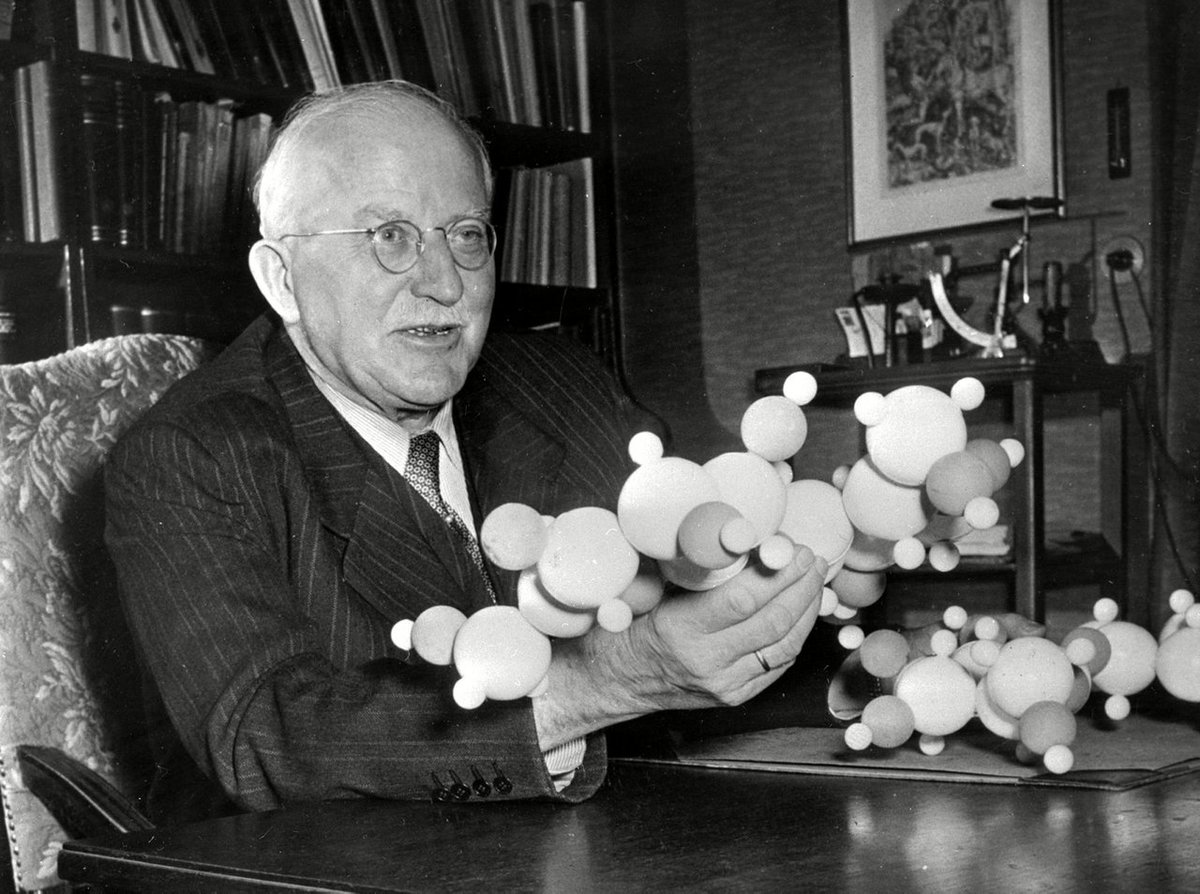

Louis Néel: The Nobel Laureate Who Revolutionized Magnetism Research

Introduction

French physicist Louis Néel, born on July 10, 1903, and passing away on October 6, 2000, is best known for his groundbreaking work in magnetism, particularly for discovering antiferromagnetism. This discovery significantly advanced the field of condensed matter physics and earned him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1970. His contributions not only enriched scientific knowledge but also paved the way for practical applications in various technological fields.

Childhood and Early Education

Néel’s interest in science was evident even at a young age. Born in Marseille, France, he grew up during a period marked by significant political upheavals, including the First World War. Despite the challenging circumstances, Néel excelled academically. He studied mathematics and physics at the École Normale Supérieure de Paris, where he laid the foundations for a career that would span multiple decades and continents.

While still a student, Néel was influenced by the work of notable scientists such as Marie Curie and Henri Poincaré, figures who embodied both brilliance and integrity. These early influences helped shape his passion for physics and his commitment to scientific integrity throughout his career.

Academic Career and Early Research

Néel obtained his Ph.D. in 1929 under the supervision of André Mercier at the Collège de France in Paris. His dissertation focused on crystallography and spectroscopy, two disciplines that would later become central to his research. Following his graduation, Néel joined the CNRS (National Centre for Scientific Research) as a scientist, where he began conducting research in magnetic materials.

In the late 1930s, Néel was appointed as a professor of physics at the University of Grenoble. It was during this time that he became increasingly intrigued by magnetic phenomena. His early research involved understanding the behavior of magnetic fields in different substances and how they interacted with each other.

The Discovery of Antiferromagnetism

Néel’s most pivotal contribution to science came with his discovery of antiferromagnetism. This phenomenon involves the alignment of magnetic moments in opposite directions in a lattice structure, leading to a cancellation of the bulk magnetization. The concept was revolutionary because it explained how certain substances could maintain their magnetic properties without exhibiting permanent magnetism.

Néel published his findings in a series of papers, the most influential being “Antiferromagnetic Structure of Iron Oxydes,” which appeared in the journal Nature in 1936. In these papers, he presented evidence for the existence of antiferromagnetism in iron oxydes and described the theoretical framework that could explain these observations. This work laid the groundwork for modern-day solid-state physics and materials science.

Contributions Beyond Antiferromagnetism

Beyond antiferromagnetism, Néel made significant contributions to other areas of physics and materials science. His work on domain structures—regions within a magnetic material where the magnetic moments point in the same direction—was crucial for understanding the behavior of materials at the microscopic level. This research provided a deeper insight into how magnetic fields could affect the properties of materials.

In addition, Néel’s investigations into the effects of temperature variations on magnetic materials were groundbreaking. He demonstrated that the behavior of magnetic domains could change dramatically with temperature, leading to phenomena such as phase transitions and hysteresis. These insights are essential for developing new technologies and materials.

Nobel Prize Recognition

Despite his prolific contributions, it wasn’t until the 1960s that Néel received widespread recognition for his work. In 1968, he was elected to the Académie des Sciences, France’s highest honor for scientists. Ten years later, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics “for his fundamental work in ferromagnetism and antiferromagnetism.” Alongside his colleague Peter Debye, Néel’s prize highlighted the significance of their collaborative research on magnetic substances.

The Nobel Committee acknowledged Néel’s discovery of antiferromagnetism as one of the most important advances in physical sciences. His work opened up a new area of study and paved the way for numerous technological advancements, from data storage systems to the development of new high-temperature superconductors.

In the next segment, we will delve further into Néel’s post-Nobel career and legacy, including his educational efforts and ongoing impact on the scientific community.

Post-Nobel Career and Legacy

Following his receipt of the Nobel Prize in Physics, Néel continued to be active and influential in the scientific community. His role as a mentor and educator was no less significant than his contributions to research. He held several positions at prestigious institutions, including the Laboratory of Solid State Physics at the Centre de Recherches sur les Solides (CRNS-CNRS-Grenoble) and later became a member of the Institut d’Electronique Fondamentale at Université Paris-Sud.

Néel’s influence extended beyond academic circles. He was involved in the establishment and development of various scientific organizations and societies, including the French Society of Physics and the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics. His leadership in these organizations contributed to setting research agendas and fostering collaborations between researchers worldwide.

One of Néel’s most notable contributions after the Nobel Prize was his work on domain walls and domain boundary motion in ferromagnetic materials. These studies provided a better understanding of how magnetic domains could move within a material under the influence of an external magnetic field. This knowledge has been instrumental in developing magnetic recording devices and data storage technologies.

Néel’s research on magnetic hysteresis also had far-reaching implications. Hysteresis, a phenomenon where the magnetization of a material lags behind the applied magnetic field, is critical for the functioning of many electronic devices. Understanding this process allowed for the development of magnetic memories and sensors, among other applications.

Educational Contributions

Néel was deeply committed to educating future generations of physicists and scientists. At the University of Grenoble, he established the first laboratory dedicated to solid-state physics, where he trained numerous students and postdoctoral fellows. Many of these individuals went on to make significant contributions in their own right, carrying forward the legacy of innovation and discovery initiated by Néel.

One of his notable educational initiatives was the creation of the Doctoral School of Physics in Grenoble, which fostered interdisciplinary research and collaboration among scientists specializing in different aspects of physics. His teaching approach emphasized the importance of rigorous theoretical foundations combined with experimental verification, ensuring that his students were well-prepared to contribute meaningfully to scientific advancement.

Impact on Technology and Society

Néel’s research was not just confined to academic theory; it had practical applications that transformed various industries. The principles he elucidated have found extensive use in the electronics industry, particularly in the production of magnetic recording media. Modern hard drives, MP3 players, and other electronic devices rely heavily on the materials and technologies developed based on Néel’s groundbreaking discoveries.

Beyond consumer electronics, Néel’s work has also influenced the development of new materials for information technology and communication infrastructure. For instance, the understanding of antiferromagnetism has led to the development of spintronic devices, which utilize the intrinsic quantum mechanical properties of electrons to perform information processing tasks more efficiently.

In addition, Néel’s research on magnetic materials has been instrumental in advancing medical imaging technologies. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), a commonly used diagnostic tool in hospitals, utilizes principles derived from his work on nuclear magnetic resonance. The ability to visualize internal body structures with high precision relies on the understanding of magnetic properties that Néel contributed to.

Legacy and Honors

Néel was awarded numerous honors throughout his career, reflecting the significance of his contributions to science. Besides the Nobel Prize, he received the Franklin Medal and the Prix Max Planck from the French Academy of Sciences. He was also elected to the National Academy of Sciences in the United States, an extraordinary achievement that underscores his global influence in the field of physics.

His legacy is not just about the awards and recognitions; it lies in the foundational knowledge he imparted and the new fields and technologies he inspired. Today, the term “Néel temperature,” named after him, refers to the temperature above which a material loses its ferromagnetism or antiferromagnetism. This parameter is crucial for material scientists and engineers working in various industrial sectors.

A fitting tribute to Néel’s lifelong dedication to science is the Louis Néel Institute of Grenoble, which continues to push the boundaries of solid-state physics and materials science. Established in his honor, the institute carries out cutting-edge research and educates the next generation of scientists, ensuring that his legacy lives on.

Néel’s life and work exemplify the enduring impact of a single visionary on the scientific landscape. His contributions to magnetism and his profound insights into material properties have left an indelible mark on our understanding of the world around us. As we continue to build upon the foundations he laid, his name remains synonymous with excellence and innovation in the realm of scientific discovery.

Personal Life and Legacy

Despite a busy career and numerous accolades, Néel remained dedicated to his personal life and family. He married Marguerite Goudier in 1932, and they had two children together. His wife also played a significant role in his life, supporting his scientific endeavors and accompanying him on many international conferences and research trips.

Néel was known for his modesty and humor, which helped him navigate the sometimes complex world of academic and scientific diplomacy. He was a natural educator and communicator, able to explain complex concepts with clarity and simplicity. This quality made him a favorite among students and colleagues alike.

One of Néel’s greatest legacies is his ability to inspire and mentor. Many of his students and postdoctoral fellows have gone on to hold prominent positions in academia and industry. His method of teaching and his open-minded approach to science nurtured a generation of scientists who continue to push the boundaries of our understanding of physical phenomena.

Néel’s contributions to science and society were recognized through various honors and recognitions. In 1973, he was awarded the Max Planck Medal by the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics, and in 1976, he received the Franklin Medal from the Franklin Institute. His work was so influential that the French government made him a Commander of the Légion d'Honneur, a high honor that recognized his significant contributions to the field of science for the betterment of society.

Impact on the Scientific Community

The impact of Néel’s work is multifaceted and far-reaching. His discovery of antiferromagnetism and his contributions to the understanding of magnetic domains and hysteresis opened up new avenues of research and applications in various scientific fields. The principles he elucidated have not only advanced our understanding of the microscopic world but have also had practical applications in numerous industries.

One of the most significant impacts of Néel’s discoveries is in the field of information technology. His work on magnetic materials has enabled the development of more efficient and reliable storage devices, contributing to the rapid progress in computer science and telecommunications. The principles of magnetism he studied have also led to the development of new materials with unique magnetic properties, which are being explored for their potential in quantum computing and other advanced technologies.

In addition to these technological advancements, Néel’s work has had an educational impact that extends beyond the classroom. His books and lectures have served as essential resources for students and researchers, providing a solid foundation for future generations. His texts on magnetism remain referenced and studied, contributing to the ongoing advancement of the field.

Memorial and Legacy Fund

To honor Néel’s contributions, a number of memorials and foundations have been established. The Louis Néel Institute for Magnetism, located in Grenoble, continues to conduct cutting-edge research and education in the field of magnetism. Named in his honor, this institution carries on his legacy by advancing the frontiers of knowledge in solid-state physics and materials science.

A more personal tribute comes in the form of the Louis Néel Legacy Fund, which supports research and educational initiatives in the fields of physics and material sciences. This fund ensures that Néel’s vision and passion for scientific exploration continue to inspire and support future scientists.

Conclusion

Louis Néel’s life and work have left an indelible mark on the world of science. From his early days as a student to his later years as a renowned scientist and educator, Néel’s contributions have shaped the way we understand and utilize the properties of matter. His pioneering work on antiferromagnetism and his insights into the behavior of magnetic materials have opened up new avenues of research and development.

Through his educational efforts and his influence on the scientific community, Néel has ensured that the principles he discovered continue to inspire and inform the next generation of scientists. His legacy is not just about the accolades he received but about the lasting impact of his contributions to our understanding of the physical world and their applications in technology and society.

As we look back on Néel’s life, we are reminded of the importance of curiosity, dedication, and collaboration in the pursuit of scientific knowledge. Louis Néel’s story is a testament to the power of human curiosity and the transformative impact of scientific discovery.

Néel’s life and contributions were a testament to the enduring pursuit of knowledge and the potential of scientific research to benefit humankind. Through his visionary work and unwavering dedication, Louis Néel has left a legacy that continues to inspire and guide scientific inquiry in the modern era.

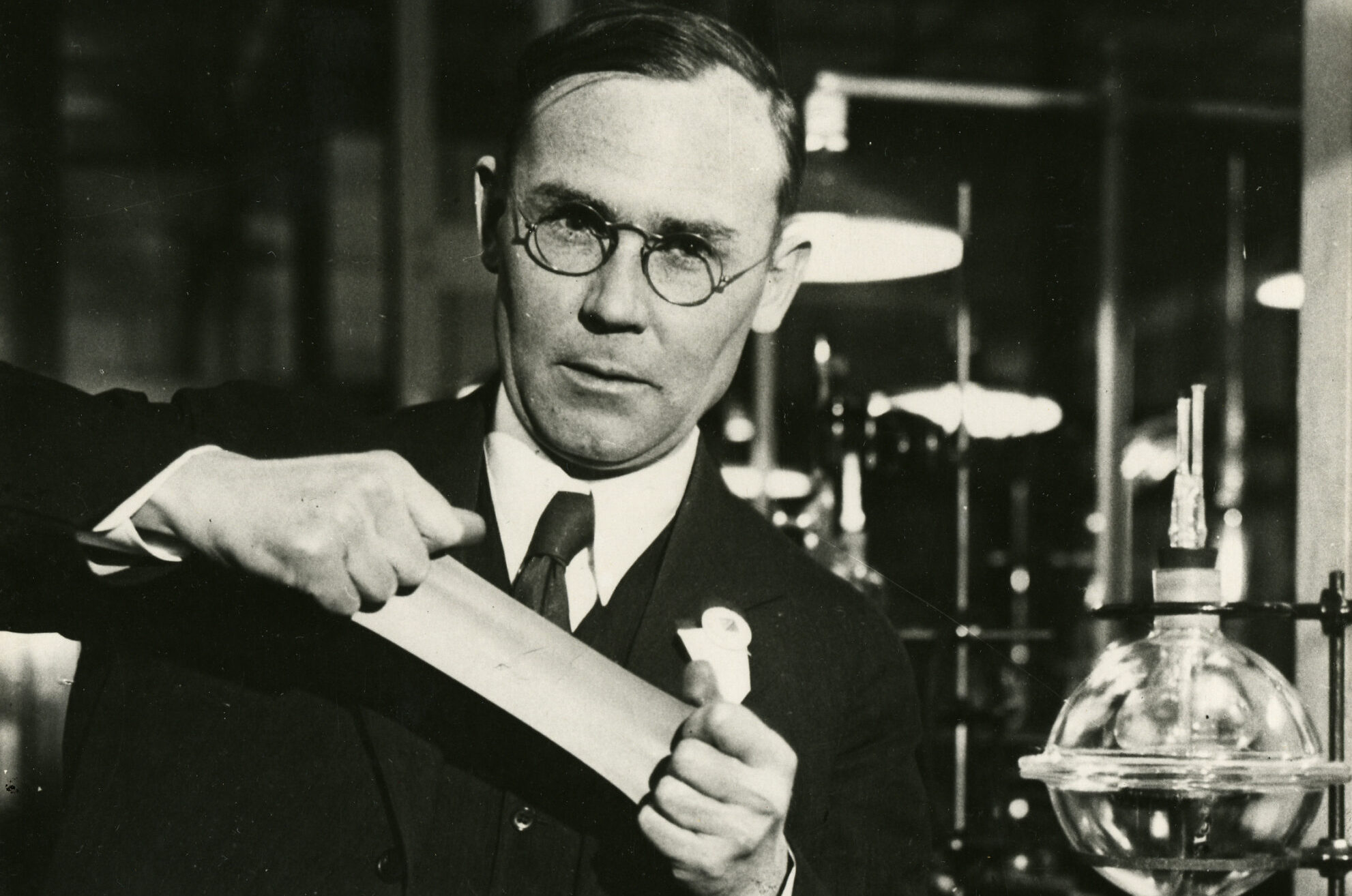

Hermann Staudinger: Pioneering Research in Macromolecular Chemistry

Life and Early Career

Hermann Staudinger, born on April 19, 1881, in Riezlern, Austria, was a groundbreaking organic chemist who laid the foundations of macromolecular science. His exceptional scientific contributions led to him being awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1953, which he shared with polystyrene pioneer Karl Ziegler. Staudinger's lifelong dedication to the study of large molecules, initially met with skepticism, eventually revolutionized the field of polymer chemistry.

Staudinger grew up in a family deeply rooted in engineering; his father ran a textile plant. This environment instilled in him a practical understanding of technology from an early age, which later proved invaluable in his chemical research. After completing his secondary education, Staudinger enrolled at the University of Innsbruck in 1900 to study chemistry and mathematics. Here, he laid the groundwork for his future academic endeavors.

His studies were not without challenges. At that time, the prevailing belief among chemists was that there was a hard limit to molecule size, known as the high molecular weight problem. Many doubted the existence of long-chain molecules because they lacked the empirical evidence needed to support such theories. Nevertheless, Staudinger believed in the potential of these large molecules and pursued his ideas with unwavering conviction.

In 1905, Staudinger earned his doctorate from the University of Berlin with a dissertation entitled "Studies on Indigo," under the supervision of Emil Fisher, a leading figure in the field of organic chemistry. This experience marked the beginning of his formal training in chemistry. Subsequently, he worked at several universities, including the University of Strasbourg (1907-1914) and the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (1914-1920), where he conducted pioneering research into the behavior of large molecules.

The Concept of Polymers

Staudinger's breakthrough came while he was a professor at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich. In 1920, during a lecture for one of his students, Hans Baeyer, Staudinger suggested that large molecules could be built up from repeated units or monomers. He hypothesized that these macromolecules had a vast array of potential applications, ranging from synthetic polymers like rubber and plastics to more complex materials with unique properties.

This concept was revolutionary because it fundamentally changed how chemists viewed the nature of materials. Prior to Staudinger’s proposal, molecules were considered to be rigid and finite structures, with each atom having a fixed place in a limited-sized chain. Through his research, Staudinger demonstrated that large molecules could exist and possess a wide range of properties due to their extended structure. His work opened up new avenues for the synthesis of novel polymers with specific characteristics tailored for various industrial applications.

To support his theory, Staudinger conducted experiments involving the analysis of macromolecules using ultracentrifuges. These instruments allowed precise measurements of molecular weights, providing irrefutable evidence for the existence of long-chain molecules. Over time, this experimental work solidified the scientific community's understanding of macromolecules.

Staudinger's theoretical framework and experimental techniques paved the way for numerous advancements in polymer chemistry. His hypothesis on macromolecules sparked extensive research into polymerization processes, enabling chemists to develop new methods for synthesizing polymers with desired properties. The discovery had profound implications for industries ranging from manufacturing and construction to healthcare and electronics.

Although the initial reception of Staudinger’s ideas was lukewarm, his persistence and rigorous experimentation ultimately won over even his skeptics. His vision of macromolecules not only revolutionized the field of polymer chemistry but also spurred advancements in related disciplines such as materials science and biochemistry.

Pioneering Contributions

Staudinger's work on macromolecules was far-reaching, encompassing a wide range of topics that expanded our understanding of material science. One area of significant contribution was the development of polymerization reactions. Through careful experimentation, Staudinger elucidated mechanisms for both addition and condensation polymerizations, providing chemists with tools to create polymers with diverse functionalities.

Addition polymerization involves the linkage of monomer units via chemical bonds between double or triple carbon-carbon bonds. Staudinger demonstrated that under appropriate conditions, simple molecules like ethylene could polymerize to form long chains of polyethylene. These findings were crucial for the development of plastic products such as films, bottles, and fibers.

Condensation polymerization, on the other hand, involves reactions where two or more molecules react with the elimination of small molecules like water or methanol. Staudinger's research showed that polyesters and polyamides could be synthesized through this mechanism. These compounds have applications in textiles, coatings, and adhesives.

Staudinger's insights extended beyond just the synthesis of polymers. He also made significant contributions to the understanding of the physical properties of macromolecules. Through his meticulous studies, he discovered that macromolecules could exhibit unique behaviors, such as entanglements and phase transitions, leading to phenomena like elasticity and viscosity.

The application of these discoveries was immense. For instance, the ability to produce synthetic rubber with elasticity similar to natural rubber transformed the tire industry, drastically reducing dependence on natural latex imports. Other industries, including packaging, textiles, and pharmaceuticals, also benefited from the enhanced understanding of polymer behavior.

Staudinger's interdisciplinary approach further distinguished his work. By integrating concepts from physics, engineering, and biology, he created a comprehensive framework for studying polymers. His research bridged gaps between traditional silos of chemistry, leading to more holistic solutions in material design.

Throughout his career, Staudinger maintained a relentless pursuit of knowledge. He collaborated extensively with other scientists and engineers, fostering a collaborative scientific community essential for advancing the field. These collaborations resulted in numerous publications and patents, cementing his legacy as a trailblazer in macromolecular chemistry.

Innovative Experimental Techniques

As Staudinger delved deeper into his research, he developed innovative experimental techniques to validate his hypotheses about macromolecules. One such method involved the use of ultracentrifugation, which allowed him to measure the molecular weights of polymers with unprecedented accuracy. By applying centrifugal forces, these devices could separate macromolecules based on their sizes, providing concrete evidence for their existence.

Another critical technique Staudinger employed was fractionation by solvent extraction. This method involved dissolving polymers in solvents with different polarities and gradually removing them to isolate fractions of varying molecular weights. This procedure helped refine his understanding of polymer structure and confirmed the presence of long-chain molecules.

Staudinger also utilized chromatography to analyze the components of polymers. Chromatographic separation techniques allowed him to identify and quantify the monomer units that comprised the macromolecules, further supporting his theory. These experiments provided tangible proof that large molecules could indeed be constructed from smaller monomers, laying the groundwork for the systematic exploration of polymer chemistry.

Moreover, Staudinger's work on rheology—a field concerned with the flow of deformable materials—was instrumental in understanding the physical properties of macromolecules. Rheological studies involved measuring the viscosity and elasticity of polymer solutions and melts, which revealed the unique behaviors of these molecules under various conditions.

Impact on Industrial Applications

The implications of Staudinger’s discoveries extended far beyond academic settings. They had transformative effects on various industrial processes, particularly in the production of synthetic polymers. One of the most notable outcomes was the creation of synthetic rubbers, which became crucial in World War II due to the disruption of natural rubber supplies from Asia.

During the war, many countries focused on developing synthetic alternatives to natural rubber. American companies like DuPont developed neoprene, a flexible synthetic rubber made from chloroprene, and other companies produced butyl rubber. German companies, influenced by Staudinger's theories, also developed similar materials to meet industrial demands.

Post-war, the development of synthetic polymers continued to boom. Companies worldwide began exploring new forms of polymerization and synthesis methods, leading to the proliferation of plastic products across various industries. Polyethylene, nylon, polyesters, and many other materials became staple commodities that reshaped everyday life.

The advent of plastic bags, disposable containers, and durable industrial components all benefited from Staudinger’s research. These innovations not only enhanced manufacturing efficiency but also provided more sustainable alternatives compared to earlier products. For instance, the development of high-strength fiber-reinforced composites has dramatically improved the performance of aerospace and automotive parts.

Furthermore, Staudinger's work laid the foundation for biocompatible polymers, which are now widely used in medical applications. Bioresorbable sutures, drug delivery systems, and artificial implants have all been developed thanks to the principles established by Staudinger. The field of biomaterials continues to advance, driven by ongoing innovations in polymer science.

Recognition and Legacy

Staudinger's groundbreaking work did not go unnoticed by the scientific community. In recognition of his contributions to chemistry, he received numerous awards and honors throughout his career. Most notably, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1953, alongside Karl Ziegler for their discoveries in the area of high-molecular-weight compounds. This accolade cemented his status as one of the giants in the field of organic chemistry.

Staudinger also held several prestigious positions during his lifetime. In 1920, he became a full professor at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich, where he would spend over three decades conducting groundbreaking research. Later in his career, he accepted a position at the University of Freiburg (1953-1966) and served as its rector from 1956 to 1961. These roles provided him platforms to mentor the next generation of chemists, ensuring that his vision lived on.

The impact of Staudinger's work extends beyond individual recognition. His theories and experiments formed the bedrock upon which an entire field of study was built. Thousands of chemists around the world followed in his footsteps, pushing the boundaries of what was possible with polymers. Today, macromolecular chemistry is a vibrant discipline with applications in areas ranging from nanotechnology to renewable energy.

Staudinger's legacy is not limited to science alone. His dedication to rigorous experimentation and his willingness to challenge prevailing paradigms have inspired countless researchers. His approach to tackling complex problems by combining theoretical insights with practical solutions remains an exemplary model for scientists today.

Awards and Honors

Beyond the Nobel Prize, Staudinger accumulated a substantial list of accolades that underscored his standing in the scientific community. In addition to the Nobel Prize, he received the Max Planck Medal (1952), the Faraday Medal (1955), and the Davy Medal (1962). These awards not only recognized his outstanding contributions but also highlighted his impact on both the theoretical and applied aspects of chemistry.

Staudinger's leadership and mentorship were also widely acknowledged. He played a pivotal role in fostering an environment conducive to innovation, nurturing a culture of inquiry and collaboration. Many of his students went on to make significant strides in their respective fields, carrying forward the torch of macromolecular research.

Staudinger's influence extended to international organizations as well. He was elected a foreign member of the Royal Society (1949) and served as a member of the German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina. These memberships attested to his global reputation in the sciences and underscored his contributions to the advancement of knowledge on a global scale.

Moreover, Staudinger's impact was also felt through his public lectures and writings. Despite his retiring personality, he found ways to communicate complex scientific ideas to a broader audience. His popular scientific writing and public talks helped bridge the gap between academia and society, inspiring both experts and laypeople alike.

Conclusion

Hermann Staudinger's journey from a skeptical environment to becoming a pioneering figure in macromolecular chemistry exemplifies the power of persistent scientific inquiry. His bold hypotheses and rigorous experimental methods paved the way for significant advancements in polymer science, impacting industries across the globe. His legacy continues to inspire chemists and materials scientists, ensuring that the importance of understanding and manipulating large molecules endures.

As we reflect on Staudinger's contributions, it becomes clear that his work represents not just a turning point but an entire era of chemical innovation. His dedication to challenging conventional wisdom and his commitment to evidence-based research laid the foundation for modern polymer chemistry, shaping the world we live in today.

Modern Relevance and Future Directions

Today, the foundational principles established by Staudinger continue to be relevant, driving new discoveries and technological advancements. Polymer science, once seen as a niche field, has become an integral part of contemporary research. Innovations in nanotechnology, biomedicine, and sustainable materials have all been influenced by Staudinger’s initial insights into macromolecular chemistry.

In nanotechnology, the control over molecular structure at the nanoscale has enabled the development of advanced materials with tailored properties. These materials find applications in electronics, where nanofabrication techniques rely heavily on precise manipulation of macromolecules. Similarly, in biotechnology, the integration of polymers into biomedical devices and therapies owes much to the principles pioneered by Staudinger.

The sustainability crisis has also seen the emergence of eco-friendly polymers. Research into biodegradable polymers that can replace conventional plastics is a direct result of the fundamental understanding of macromolecular chemistry. Bioplastics, derived from renewable resources, promise to reduce environmental impacts by providing sustainable alternatives to petrochemical-derived plastics.

Moreover, advances in computational chemistry now allow researchers to simulate and predict the behavior of complex macromolecules. Molecular dynamics simulations and quantum mechanical calculations have become essential tools for designing new polymers and understanding their properties. These techniques, built on the theoretical underpinnings established by Staudinger, are pushing the boundaries of what is achievable in material science.

Applications in Industry

The applications of macromolecular chemistry extend far beyond academic research. Industries such as pharmaceuticals, aerospace, and automotive have leveraged Staudinger’s discoveries to develop cutting-edge products. In the pharmaceutical sector, biodegradable polymers are used in drug delivery systems that control the release of medications over time. These systems can improve therapeutic efficacy and minimize side effects.

In the aerospace and automotive industries, lightweight yet strong materials are crucial for reducing fuel consumption and improving safety. Advanced composite materials, composed of reinforced polymers, offer the required strength-to-weight ratio. Staudinger’s insights into the behavior of macromolecules under stress conditions help engineers design safer and more efficient vehicles.

The textile industry has also benefitted significantly from macromolecular research. The development of smart fabrics that respond to environmental stimuli, such as temperature or moisture, relies on the understanding of macromolecular interactions. These materials are not only functional but also sustainable, offering alternatives to traditional materials that may be harmful to the environment.

Innovation in Sustainable Materials

Sustainability is a key focus area in the development of new polymers. Researchers are increasingly looking to natural and renewable sources for producing biopolymers. Plant-based materials, such as cellulose, starch, and lignin, offer viable alternatives to petrochemical plastics. By optimizing these natural polymers and developing new synthesis methods, scientists aim to create materials that are both eco-friendly and performant.

Innovations in green chemistry are also driven by Staudinger's legacy. The principle of using less toxic and less hazardous substances in the synthesis of polymers is a direct outcome of his emphasis on rigorous experimentation and evidence-based research. Green materials, characterized by minimal waste and recyclability, align with the growing demand for environmentally responsible practices.

Furthermore, the development of new polymers for energy applications is another emerging area. Organic solar cells, for instance, rely on the manipulation of macromolecules to harvest sunlight efficiently. Staudinger's insights into polymer behavior under various conditions inspire new strategies for optimizing these devices, potentially revolutionizing renewable energy solutions.

Conclusion

Hermann Staudinger's contributions to macromolecular chemistry have had a lasting impact on almost every aspect of materials science and technology. From synthetic rubbers and plastics to advanced biodegradable materials and sustainable energy solutions, his foundational work continues to drive innovation and inspire future generations of scientists.

As we stand on the shoulders of his giants, it is evident that the journey of exploring macromolecules is far from over. New challenges continue to emerge, from developing more efficient polymers to addressing the environmental impact of materials. Staudinger's legacy serves as a reminder of the importance of persistent questioning and rigorous investigation in advancing our scientific knowledge.

Through his visionary ideas and relentless pursuit of understanding, Hermann Staudinger has left an immeasurable mark on the field of chemistry. His work not only paved the way for countless applications but also shaped our understanding of the molecular world. As we continue to push the boundaries of what is possible with polymers, we honor his legacy by building upon his foundational discoveries.

Jacques Monod: A Pioneer of Molecular Biology

Early Life and Education

Jacques Lucien Monod was born on February 9, 1910, in Paris, France. From an early age, Monod exhibited a keen interest in the natural sciences, a passion that was nurtured by his father, Lucien Monod, a painter and intellectual. Monod's upbringing in an intellectually stimulating environment laid the foundation for his future contributions to science. He attended the Lycée Carnot in Paris, where he excelled in his studies, particularly in biology and chemistry. His fascination with life sciences led him to pursue higher education at the University of Paris, where he earned his bachelor's degree in 1931.

Monod's academic journey took a significant turn when he joined the laboratory of André Lwoff at the Pasteur Institute. Under Lwoff's mentorship, Monod developed a deep understanding of microbial physiology and genetics. This period was crucial in shaping his scientific outlook, as he began to explore the mechanisms of enzyme adaptation in bacteria. His early research laid the groundwork for what would later become his most celebrated contributions to molecular biology.

Scientific Contributions and the Operon Model

One of Jacques Monod's most groundbreaking achievements was his work on the regulation of gene expression, which he conducted in collaboration with François Jacob. Together, they proposed the operon model, a revolutionary concept that explained how genes are controlled in bacteria. The operon model describes a cluster of genes that are transcribed together and regulated by a single promoter. This discovery provided profound insights into how cells switch genes on and off in response to environmental changes.

The lac operon, a specific example studied by Monod and Jacob, became a cornerstone of molecular biology. It demonstrated how the presence or absence of lactose in the environment could trigger or inhibit the production of enzymes needed to metabolize it. This elegantly simple yet powerful model earned Monod and Jacob the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1965, shared with André Lwoff, for their discoveries concerning genetic control of enzyme and virus synthesis.

Philosophical and Ethical Perspectives

Beyond his scientific achievements, Jacques Monod was a thinker who engaged deeply with philosophical and ethical questions. In his book "Chance and Necessity" (1970), Monod explored the implications of molecular biology for understanding life's origins and evolution. He argued that life arose from random molecular interactions, governed by the laws of chemistry and physics, and that evolution was driven by chance mutations and natural selection. This perspective challenged traditional notions of teleology, the idea that life has an inherent purpose or direction.

Monod's philosophical stance often placed him at odds with religious and ideological doctrines that emphasized predetermined design in nature. His views sparked debates not only in scientific circles but also among theologians and philosophers. Despite the controversy, Monod remained steadfast in his belief that science, grounded in empirical evidence, was the most reliable path to understanding the universe and humanity's place within it.

Legacy and Influence

Jacques Monod's legacy extends far beyond his scientific discoveries. He played a pivotal role in establishing molecular biology as a distinct discipline, bridging the gaps between biochemistry, genetics, and microbiology. His work laid the foundation for countless advancements in genetic engineering, biotechnology, and medicine. Today, the principles he elucidated continue to guide research in gene regulation and cellular function.

Monod's influence also permeated the scientific community through his leadership roles. He served as the director of the Pasteur Institute from 1971 to 1976, where he fostered a collaborative and innovative research environment. His dedication to scientific rigor and intellectual freedom inspired generations of researchers to pursue bold and transformative ideas.

In recognition of his contributions, Monod received numerous accolades, including the Nobel Prize, membership in prestigious academies, and honorary degrees from universities worldwide. His name lives on in the names of institutions, awards, and even a crater on the moon, honoring his indelible mark on science and human knowledge.

The War Years and Resistance Efforts

Jacques Monod's life took a dramatic turn during World War II, when he became an active member of the French Resistance. Despite the risks, Monod joined the underground movement, using his scientific expertise to aid the Allied cause. He worked closely with the resistance network "Combat," forging documents, smuggling intelligence, and even assisting in sabotage operations against Nazi forces. His bravery and strategic thinking made him a key figure in the resistance, though he rarely spoke about his wartime experiences later in life.

During this turbulent period, Monod also continued his scientific research under difficult conditions. The Pasteur Institute, where he worked, became a hub for clandestine activities, with scientists discreetly conducting experiments while secretly aiding the resistance. Monod's dual role as a researcher and a resistance fighter exemplified his unwavering commitment to both science and liberty. His experiences during the war profoundly influenced his later perspectives on ethics, freedom, and the responsibilities of scientists in society.

Post-War Research and the Birth of Molecular Biology

After the war, Monod returned to full-time research, focusing on the study of bacterial enzymes and their regulation. His work in the late 1940s and 1950s sought to understand how microorganisms adapted to changes in their environment. A pivotal breakthrough came when Monod, alongside collaborators like François Jacob and André Lwoff, developed the concept of "enzyme adaptation." This research eventually led to the formulation of the operon theory, which explained how genes could be turned on or off in response to environmental cues.

The discovery of messenger RNA (mRNA) was another landmark moment in Monod’s career. By demonstrating that RNA acted as an intermediary between DNA and protein synthesis, Monod and Jacob provided a crucial piece of the puzzle in understanding how genetic information is expressed. Their experiments with E. coli bacteria revealed that gene expression was not static but tightly controlled, laying the groundwork for the modern understanding of gene regulation.

Collaboration with François Jacob and the Nobel Prize

The partnership between Jacques Monod and François Jacob was one of the most prolific in the history of molecular biology. Their complementary skills—Monod’s biochemical precision and Jacob’s genetic insights—allowed them to tackle complex biological questions with remarkable clarity. One of their most famous collaborations involved studying the lactose metabolism in E. coli, which led to the discovery of the lac operon. This system demonstrated how bacteria could economize resources by producing enzymes only when needed, a principle later found to be universal in living organisms.

In 1965, Monod, Jacob, and Lwoff were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discoveries concerning genetic regulation and viral replication. The Nobel committee acknowledged that their work had fundamentally changed the way scientists understood cellular function. For Monod, the prize was not just a personal triumph but a validation of molecular biology as a transformative scientific discipline.

Monod’s Leadership in Science and Policy

Beyond the lab, Monod played a crucial role in shaping science policy and institutional governance. In 1971, he became the director of the Pasteur Institute, where he implemented reforms to modernize research practices and encourage interdisciplinary collaboration. His leadership emphasized rigor, creativity, and intellectual freedom—values he believed essential for scientific progress.

Monod was also an outspoken advocate for the role of science in society. He believed that rational thinking and empirical evidence should guide public decision-making, a stance that occasionally brought him into conflict with political and religious authorities. His critiques of dogma and pseudoscience were sharp, and he often warned against the dangers of ideology overriding evidence. Monod’s vision extended beyond academia; he saw science as a force for human progress, capable of addressing global challenges such as disease, hunger, and environmental crises.

Controversies and Philosophical Debates

Monod’s book "Chance and Necessity" (1970) was not only a scientific treatise but also a philosophical manifesto. In it, he argued that the universe was inherently devoid of predetermined purpose, and life arose from a combination of chance mutations and deterministic biochemical laws. This perspective clashed with teleological and religious worldviews, sparking widespread debate. Critics accused Monod of promoting a bleak, materialistic vision of existence, while others praised his intellectual honesty and defense of scientific rationality.

Despite the controversy, Monod’s ideas resonated with many scientists and thinkers who saw them as a bold reaffirmation of the Enlightenment’s values. His insistence that humanity must create its own meaning in an indifferent universe became a touchstone for secular humanism. Decades later, his arguments still influence discussions about the intersection of science, philosophy, and ethics.

Final Years and Lasting Impact

In his later years, Monod remained an active voice in scientific and intellectual circles, though his health began to decline due to complications from anemia. He passed away on May 31, 1976, but his legacy endured through the countless researchers who built upon his work. Monod had an extraordinary ability to bridge disciplines—moving seamlessly from biochemistry to genetics to philosophy—and his holistic approach continues to inspire scientists today.

His influence can be seen in fields ranging from synthetic biology to cancer research, where the principles of gene regulation he uncovered remain foundational. Institutions like the Jacques Monod Institute in France honor his contributions by fostering cutting-edge research in molecular and cellular biology. Monod’s life and work stand as a testament to the power of curiosity, courage, and reason in unlocking the mysteries of life.

Monod's Enduring Scientific Principles

The fundamental concepts Jacques Monod helped establish continue to shape modern biological research with remarkable precision. His work on allostery - the regulatory mechanism where binding at one site affects activity at another - remains a cornerstone of biochemistry and pharmacology. Today, approximately 60% of drugs target allosteric proteins, demonstrating the profound practical implications of Monod's theoretical framework. The molecular switches he studied in bacteria operate with similar logic in human cells, governing everything from hormone reception to neuronal signaling.

Recent advances in cryo-electron microscopy have revealed the intricate structural dynamics that Monod could only hypothesize about. High-resolution snapshots of the lactose repressor protein, first characterized by Monod's team, show extraordinary atomic-scale choreography that validates his prediction about conformational changes in regulatory proteins. Contemporary researchers continue discovering new layers of complexity in gene regulation that still adhere to the basic principles Monod established - feedback loops, threshold responses, and modular control systems that optimize cellular function.

The Evolution of His Ideas in Systems Biology

Monod's quantitative approach to studying biological systems anticipated the formal discipline of systems biology by several decades. His insistence on precise mathematical modeling of cellular processes - famously declaring "What's true for E. coli must be true for elephants" - set a standard for rigor in biological research. Modern systems biologists implementing Monod's philosophy have uncovered remarkable parallels between bacterial gene networks and human signaling pathways, proving many of his conceptual leaps correct.

The development of synthetic biology particularly owes a debt to Monod's work. Bioengineers routinely construct genetic circuits based on modified operons that function as biological logic gates, realizing Monod's vision of biology as an engineering discipline. Researchers at MIT recently created a complete synthetic version of the lac operon, replacing natural components with designed analogs while preserving its regulatory logic - a tribute to how thoroughly Monod decoded this system.

Philosophical Legacy in Contemporary Science

Monod's philosophical arguments in "Chance and Necessity" have gained renewed relevance in today's debates about artificial intelligence, complexity, and emergence. His insistence on distinguishing between objective knowledge and subjective values remains a guiding principle in scientific ethics. Modern theoretical biologists grappling with questions of consciousness and free will often find themselves rephrasing arguments first articulated by Monod about the interplay between deterministic laws and probabilistic events in living systems.

Neuroscientist Antonio Damasio acknowledged Monod's influence when proposing that homeostatic regulation in cells represents a primitive form of "value" that preceded nervous systems. This extension of Monod's concepts demonstrates how his ideas continue evolving across disciplinary boundaries. Similarly, researchers studying the origins of life now approach the chemical-to-biological transition using Monod's framework of molecular chance constrained by thermodynamic necessity.

Educational Initiatives and Institutional Impact

The Institut Jacques Monod in Paris stands as a living monument to his interdisciplinary vision, where physicists, chemists, and biologists collaborate on problems ranging from epigenetic inheritance to cell motility. Current director Jean-René Huynh notes that "Monod's spirit of asking fundamental questions while developing rigorous methods animates all our departments." Remarkably, over 40% of the institute's research straddles traditional discipline boundaries, fulfilling Monod's belief that major advances occur at intersections.

Educational programs inspired by Monod's approach have emerged worldwide. The Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory's summer courses teach gene regulation using Monod's heuristic of isolating principles from specific examples. At Stanford University, the BIO 82 course recreates classic Monod-Jacob experiments while adding modern genomic analysis, letting students experience both the historical foundations and current extensions of their work.

Unfinished Questions and Active Research Frontiers

Several mysteries Monod identified remain hot research topics. His observation that regulatory networks exhibit both robustness and sensitivity - now called the "Monod paradox" - continues challenging systems biologists. Teams at Harvard and ETH Zürich are testing whether this represents an evolutionary optimum or inevitable physical constraint using synthetic gene networks inserted into different host organisms.

The phenomenon of bistability that Monod observed in bacterial cultures now explains cellular decision-making in cancer progression and stem cell differentiation. Researchers at Memorial Sloan Kettering recently demonstrated how Monod-style positive feedback loops maintain drug resistance in leukemia cells, suggesting novel therapeutic approaches by targeting these ancient regulatory motifs.

Personal Legacy and Influence on Scientific Culture

Monod's analytical rigor coupled with creative intuition created a template for scientific excellence that mentees like Jeffey W. Roberts and Mark Ptashne carried forward. His famous quote "Science is the only culture that's truly universal" encapsulates his commitment to science as a humanistic enterprise. This vision manifests today in initiatives like the Human Cell Atlas project, which applies Monodian principles of systematic analysis to map all human cells.

Contemporary leaders often cite Monod's emphasis on methodological purity. CRISPR pioneer Jennifer Doudna keeps a copy of "Chance and Necessity" in her office, noting its influence on her thinking about scientific responsibility. Similarly, Nobel laureate François Englert credits Monod for demonstrating how theoretical boldness must be matched by experimental rigor - lessons that guided his Higgs boson research.

A Comprehensive Scientific Vision

Jacques Monod's career embodies the complete scientist - experimentalist, theorist, philosopher, and leader. From the molecular details of protein-DNA interactions to the grand questions of life's meaning, he demonstrated how science could illuminate multiple levels of reality. The Monod Memorial Lecture at the Collège de France annually highlights work that bridges these dimensions, from quantum biology to astrobiology.

As we enter an era of programmable biology and artificial life, Monod's insights provide both foundation and compass. His distinctions between invariance (genetic stability) and teleonomy (goal-directed function) help researchers navigate existential questions about synthetic organisms. The "Monod Test" has become shorthand for assessing whether biological explanations properly distinguish mechanistic causes from evolutionary origins.

Conclusion: An Ever-Evolving Legacy

Jacques Monod's influence continues expanding beyond what even he might have imagined. Recent discoveries about non-coding RNA regulation, phase separation in cells, and microbiomes all connect back to principles he established. As we decode more genomes but still struggle to predict phenotype from DNA sequence, Monod's warning about the complexity of regulation seems increasingly prophetic.

The ultimate tribute to Monod may be that his ideas have become so fundamental they're often taught without attribution - the highest form of scientific immortality. Yet returning to his original writings still yields fresh insights, proving that great science, like the operons he studied, remains perpetually relevant when grounded in universal truths about how life works at its core.

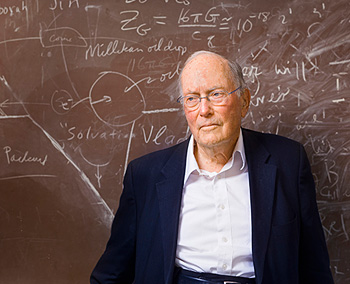

Carl Wieman: A Pioneer in Physics and Science Education

Introduction

Carl Wieman is a name synonymous with groundbreaking contributions to both physics and science education. A Nobel laureate in Physics, Wieman’s work has not only advanced our understanding of quantum mechanics but also revolutionized how science is taught in classrooms worldwide. His journey from a curious young physicist to a globally acclaimed educator is a testament to his relentless pursuit of knowledge and dedication to improving science literacy. This article explores Wieman’s early life, his pivotal discoveries in physics, and his transformative impact on education.

Early Life and Academic Background

Born on March 26, 1951, in Corvallis, Oregon, Carl Edwin Wieman displayed an early fascination with the natural world. His parents, both educators, nurtured his curiosity, fostering a love for learning that would shape his future. Wieman attended Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he earned his bachelor’s degree in 1973. He then pursued his PhD at Stanford University, completing it in 1977 under the supervision of renowned physicist Theodor Hänsch.

Wieman’s graduate research focused on precision measurements in atomic physics, a field that would later become central to his Nobel Prize-winning work. After earning his doctorate, Wieman held positions at the University of Michigan and the University of Colorado Boulder, where he would make some of his most significant scientific breakthroughs.

The Nobel Prize-Winning Achievement: Bose-Einstein Condensate

Carl Wieman’s most celebrated contribution to physics came in 1995 when he, along with Eric Cornell and Wolfgang Ketterle, successfully created a Bose-Einstein condensate (BEC) in a laboratory. This achievement confirmed a prediction made by Albert Einstein and Satyendra Nath Bose in the 1920s, demonstrating that at extremely low temperatures, atoms could coalesce into a single quantum state, behaving as a "superatom."

The creation of BEC was a monumental feat that opened new frontiers in quantum physics. It allowed scientists to study quantum phenomena on a macroscopic scale, offering insights into superfluidity, superconductivity, and quantum computing. For this pioneering work, Wieman, Cornell, and Ketterle were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2001.

Transition to Science Education Reform

While Wieman’s accomplishments in physics earned him global recognition, his passion for teaching and education soon took center stage in his career. Frustrated by the traditional, lecture-based methods of science instruction, Wieman began advocating for evidence-based teaching strategies that actively engage students in the learning process.

Wieman’s research revealed that passive lectures were ineffective in fostering deep understanding and retention of scientific concepts. Instead, he championed interactive methods such as peer instruction, collaborative problem-solving, and the use of technology to enhance learning. His work in education was not merely theoretical—he implemented these techniques in his own classrooms, demonstrating measurable improvements in student performance.

The Science Education Initiative

Wieman’s commitment to improving science education led him to establish the Science Education Initiative (SEI) at the University of Colorado Boulder and later at the University of British Columbia. The SEI aimed to transform undergraduate science courses by integrating research-backed teaching practices and assessing their impact on student learning.

The initiative proved highly successful, with participating departments reporting significant gains in student engagement, comprehension, and retention. Wieman’s approach emphasized the importance of treating teaching as a scholarly activity, where educators continuously evaluate and refine their methods based on data and evidence.

Awards and Recognitions Beyond the Nobel Prize

Carl Wieman’s influence extends far beyond his Nobel Prize. He has received numerous accolades for his contributions to both physics and education, including the National Science Foundation’s Distinguished Teaching Scholar Award and the Carnegie Foundation’s Professor of the Year designation.

In 2007, Wieman was appointed as the Associate Director for Science in the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, where he advised on federal STEM education policies. Later, he joined Stanford University as a professor of physics and education, continuing his mission to bridge the gap between scientific research and effective teaching.

Conclusion of Part One

Carl Wieman’s legacy is a rare blend of groundbreaking scientific discovery and transformative educational reform. From his Nobel Prize-winning work on Bose-Einstein condensates to his relentless advocacy for evidence-based teaching, Wieman has left an indelible mark on both academia and society. In the next part of this article, we will delve deeper into his educational philosophies, the widespread adoption of his methods, and his ongoing efforts to shape the future of science education.

Carl Wieman’s Educational Philosophy and Impact

Challenging Traditional Teaching Methods

Carl Wieman’s transition from an acclaimed physicist to a leader in education reform was driven by his frustration with conventional teaching models. He observed that most science courses relied heavily on passive lectures, where students memorized facts without truly understanding the underlying concepts. Wieman argued that this approach failed to prepare students for real-world scientific reasoning, leading to high attrition rates in STEM fields.

Through extensive research, Wieman demonstrated that interactive engagement techniques significantly improved learning outcomes. He found that methods such as clicker questions, small-group discussions, and problem-solving exercises helped students develop critical thinking skills. His studies showed that these approaches doubled or even tripled learning gains compared to traditional lectures.

The Principles of Active Learning

Central to Wieman’s educational philosophy is the concept of active learning, where students participate in the learning process rather than passively consuming information. He emphasized that effective teaching should mirror the scientific method—encouraging curiosity, experimentation, and reflection.

Wieman’s research highlighted several key components of successful science education:

- Deliberate Practice: Breaking complex topics into manageable chunks and providing guided practice with feedback.

- Peer Collaboration: Encouraging students to discuss ideas and solve problems collaboratively to deepen understanding.

- Real-World Applications: Connecting abstract theories to practical scenarios to enhance relevance and retention.

- Continuous Assessment: Using frequent, low-stakes assessments to monitor progress and adapt instruction.

The Spread of Evidence-Based Teaching Practices

Wieman’s advocacy for active learning has had a ripple effect across universities and institutions worldwide. His Science Education Initiative (SEI) became a blueprint for transforming undergraduate STEM programs. Departments that adopted SEI strategies reported not only better student performance but also increased enthusiasm for science.

One notable example is the University of British Columbia, where Wieman’s reforms led to a dramatic reduction in failure rates in introductory physics courses. Similar successes were replicated at other institutions, proving that evidence-based teaching could scale beyond individual classrooms.

Technology and the Future of Science Education

Harnessing Digital Tools for Better Learning

Recognizing the potential of technology to enhance education, Wieman pioneered the use of digital simulations and virtual labs. These tools allowed students to explore complex concepts—such as quantum mechanics or thermodynamics—in an interactive, risk-free environment.

One of his most influential contributions was the development of the PhET Interactive Simulations project at the University of Colorado. These free, web-based simulations engage learners through intuitive, game-like interfaces while maintaining rigorous scientific accuracy. Today, PhET simulations are used by millions of students and teachers globally, democratizing access to high-quality science education.

Addressing Equity in STEM Education

Wieman has consistently emphasized the need to make science education inclusive and accessible. His research revealed that underrepresented groups, including women and minorities, often face systemic barriers in traditional STEM classrooms. By emphasizing collaborative learning and reducing competitive grading structures, Wieman’s methods have helped narrow achievement gaps.

For instance, studies showed that active learning disproportionately benefited students from disadvantaged backgrounds. Wieman argued that improving teaching wasn’t just about better pedagogy—it was a matter of social justice, ensuring all students had the opportunity to excel in science.

Policy Influence and Institutional Change

Advising at the National Level