Jacques Cousteau: The Pioneer of the Deep

The Early Life of a Visionary Explorer

Jacques-Yves Cousteau was born on June 11, 1910, in Saint-André-de-Cubzac, France. From a young age, he was fascinated by the sea, though his path to becoming one of the most renowned ocean explorers of all time was not straightforward. Cousteau's early years were marked by curiosity and a rebellious spirit. He loved machines, nature, and adventure, but his formal education initially led him toward aviation.

However, a near-fatal car accident in 1933 altered the course of his life. While recovering, he was introduced to spearfishing and underwater exploration by his friend Philippe Tailliez. The experience ignited a deep passion for the ocean, setting him on a journey that would redefine marine science, conservation, and storytelling.

The Invention of the Aqua-Lung

One of Cousteau’s most significant contributions to underwater exploration was the co-invention of the Aqua-Lung in 1943. Working alongside engineer Émile Gagnan, Cousteau developed the first open-circuit, self-contained underwater breathing apparatus (SCUBA). This revolutionary device allowed divers to explore the ocean depths with unprecedented freedom and mobility, unshackled from heavy diving helmets and surface-supplied air.

The Aqua-Lung not only transformed underwater exploration but also opened new frontiers for marine biology, archaeology, and underwater filmmaking. Scientists could now study marine ecosystems firsthand, and divers could document the world beneath the waves in ways never before imagined.

The Calypso and the Beginnings of Oceanographic Expeditions

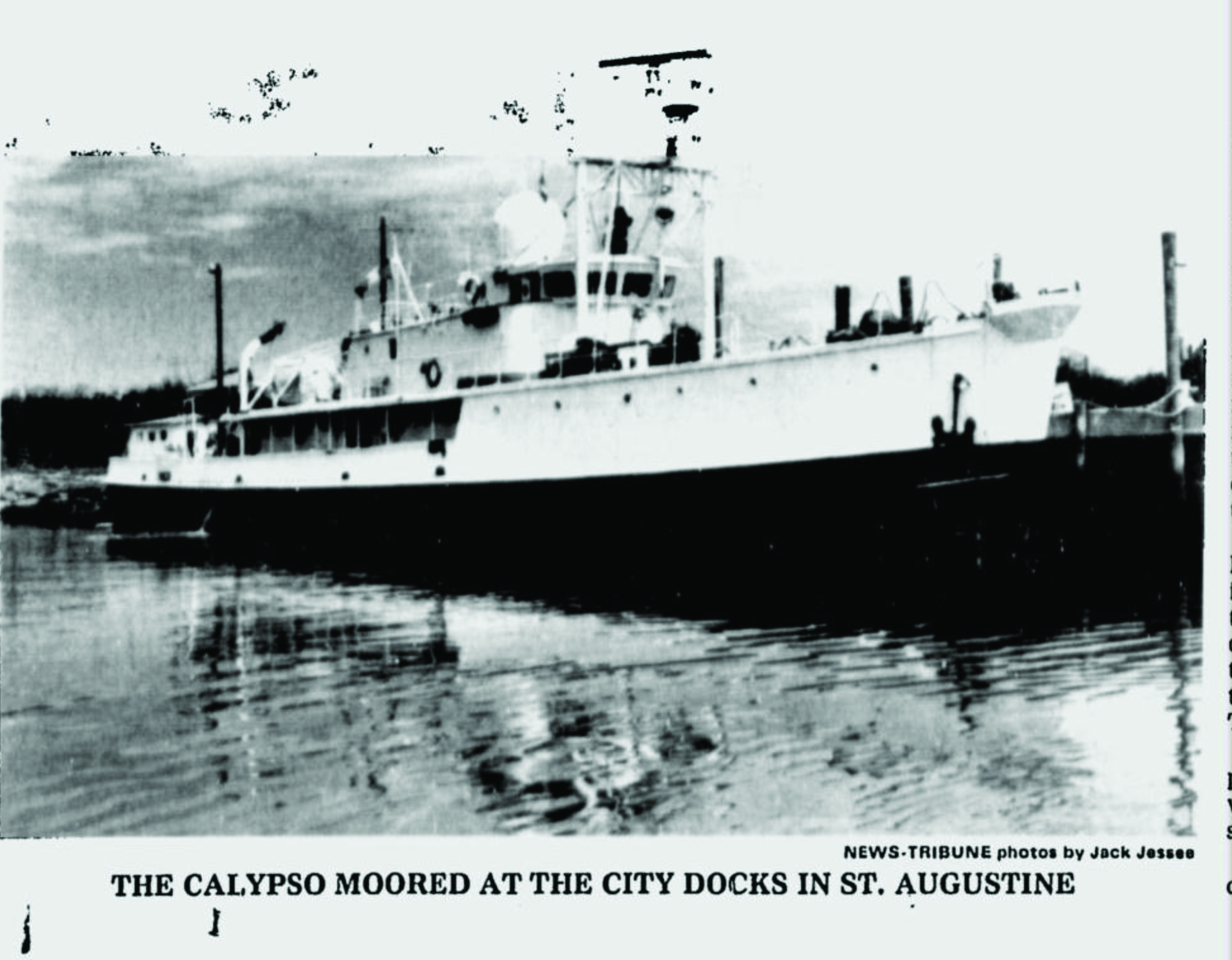

In 1950, Cousteau acquired the Calypso, a former minesweeper that he converted into a floating oceanographic laboratory. The vessel became legendary, serving as the base for Cousteau’s groundbreaking expeditions. Equipped with underwater cameras, submersibles, and diving gear, the Calypso allowed Cousteau and his team to explore remote marine environments and bring their discoveries to the public.

Through the 1950s and 1960s, Cousteau and his crew traveled the globe, documenting coral reefs, shipwrecks, and deep-sea trenches. His expeditions were not just scientific missions but also media sensations, capturing the imaginations of millions with stunning footage of previously unseen underwater worlds.

The Silent World: A Cinematic Revolution

In 1956, Cousteau released The Silent World, a documentary film co-directed with Louis Malle. Shot in vibrant Technicolor, the film showcased the beauty and mystery of the ocean, winning critical acclaim and the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. It was also the first documentary to win an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.

The Silent World was more than just a film—it was a cultural phenomenon that introduced mainstream audiences to the wonders of marine life and the fragility of ocean ecosystems. Cousteau’s ability to combine science, adventure, and cinematic artistry set a new standard for nature documentaries.

Advocacy for Marine Conservation

As Cousteau witnessed firsthand the impacts of pollution, overfishing, and habitat destruction, he evolved from an explorer into a passionate conservationist. In 1973, he founded the Cousteau Society, an organization dedicated to marine research, education, and advocacy. Through his later documentaries, books, and public campaigns, he warned of the dangers facing the ocean and called for global action to protect it.

Cousteau's legacy is not just in his technological innovations or breathtaking films but also in his enduring message: that the ocean is a vital, interconnected system that must be preserved for future generations. His work laid the foundation for modern marine conservation movements and inspired countless individuals to take up the cause of protecting the planet.

(To be continued...)

Cousteau’s Television Legacy: Bringing the Ocean into Homes Worldwide

Jacques Cousteau’s influence reached its zenith with the advent of television. In 1966, he launched The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau, a groundbreaking documentary series that aired on ABC. The show became an international sensation, captivating audiences with its stunning underwater cinematography and compelling storytelling. Viewers marveled at exotic marine creatures, vibrant coral reefs, and the eerie depths of unexplored ocean trenches—all narrated with Cousteau’s distinctive French-accented voice.

The series ran for nearly a decade, followed by other acclaimed productions like The Cousteau Odyssey and Cousteau’s Amazon. Unlike traditional nature documentaries, Cousteau’s films had a unique narrative style—blending adventure, science, and environmental ethics. He didn’t just show the underwater world; he made audiences feel emotionally invested in its preservation. His ability to humanize marine life, from playful dolphins to mysterious octopuses, set a precedent for modern environmental filmmaking.

The Birth of Underwater Archaeology

Beyond marine biology, Cousteau was a pioneer in underwater archaeology. One of his most famous expeditions was the discovery and excavation of the ancient Greek shipwreck at Grand Congloué near Marseille in 1952. Using the Aqua-Lung, Cousteau and his team recovered amphorae and artifacts, proving that shipwrecks could serve as underwater museums.

Later, in 1975, his team explored the wreck of the HMHS Britannic, the sister ship of the Titanic, using advanced diving technology. These expeditions demonstrated that the ocean floor held invaluable historical treasures—ones that could only be studied with the tools Cousteau had helped develop. His work laid the groundwork for modern maritime archaeology, inspiring future explorers to uncover lost civilizations beneath the waves.

The Tragic Loss of the Calypso

Despite its legendary status, the Calypso met a tragic fate. In 1996, while docked in Singapore, the ship was accidentally rammed by a barge and sank. Cousteau, then in his late 80s, was devastated. For nearly half a century, the Calypso had been his home, laboratory, and symbol of ocean exploration. Though efforts were made to salvage and restore the vessel, Cousteau would not live to see its full revival.

The loss of the Calypso marked the end of an era, but Cousteau’s vision endured. His expeditions aboard the ship had already cemented his status as a global icon of marine exploration, and his later projects continued to push boundaries. Even in his final years, he dreamed of new technologies—such as a wind-powered vessel called the Alcyone, featuring an experimental turbosail system designed for eco-friendly ocean travel.

Cousteau’s Later Years and Environmental Activism

As the 20th century drew to a close, Cousteau shifted his focus toward urgent environmental advocacy. He spoke at international forums, warning of climate change, ocean acidification, and the devastating effects of industrial fishing. In 1977, he co-authored The Cousteau Almanac: An Inventory of Life on a Water Planet, a comprehensive study of Earth’s water systems and the threats they faced.

Perhaps one of his most notable political campaigns was his fight against nuclear testing in the Pacific. Cousteau documented the ecological devastation caused by French atomic tests in Mururoa Atoll, using his films to lobby governments for change. His activism was not always welcomed—some saw him as an alarmist or a nuisance—but he remained steadfast. He believed that the scientist’s duty was not just to discover but to protect.

The Legacy of the Cousteau Society

Founded in 1973, the Cousteau Society became a hub for marine research and conservation. Its mission was clear: to educate the public about the fragility of the ocean and advocate for sustainable policies. Among its many projects, the society helped establish marine protected areas, funded research on endangered species, and promoted youth education through initiatives like the Water Planet Alliance.

Today, the organization continues Cousteau’s work under the leadership of his widow, Francine Cousteau, and his son, Pierre-Yves Cousteau. They campaign against deep-sea mining, plastic pollution, and overfishing—challenges that Jacques himself had warned about decades earlier. The society’s archives preserve his films, research, and writings, ensuring that future generations learn from his discoveries and warnings.

Inspiring Future Generations of Ocean Explorers

Cousteau’s influence extends far beyond his own expeditions. Film directors like James Cameron and Sylvia Earle cite him as a key inspiration for their careers. His emphasis on visual storytelling reshaped nature documentaries, paving the way for modern series like Blue Planet and Our Planet. Even in popular culture, his iconic red beanie and the silhouette of the Calypso remain symbols of adventure and environmental stewardship.

Universities and research institutions now offer marine science programs partly due to the public interest Cousteau sparked. His belief that exploration should serve a greater purpose—protection—resonates in today’s marine conservation movements. From coral reef restoration projects to citizen science initiatives, his ethos lives on.

(To be continued...)

Cousteau's Final Years and Enduring Influence

Jacques Cousteau spent his final years as a global ambassador for the oceans, though his journey was not without controversy. In the 1990s, he partnered with various corporations to fund his expeditions, drawing criticism from some environmental purists who felt he had compromised his principles. Yet even these alliances demonstrated Cousteau's pragmatic approach - he recognized that protecting the seas required engaging with industry and governments as much as opposing them. His last major project, Planet Ocean, aimed to monitor the world's water systems via satellite, reflecting his lifelong belief that technology could reveal - and potentially solve - environmental crises.

Tragically, the legendary explorer passed away on June 25, 1997 at age 87, just two weeks after celebrating his birthday. His funeral at Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris drew dignitaries from around the world, while memorial services were held simultaneously aboard ships at sea - a fitting tribute for a man who had spent more time on water than land. UNESCO established the Jacques-Yves Cousteau Award in Marine Conservation in his honor, ensuring his name would remain synonymous with oceanic protection.

The Cousteau Family Legacy Continues

The Cousteau dynasty continues to champion marine conservation through multiple generations. His second wife, Francine, maintains the Cousteau Society while his sons and grandchildren have each carved their own paths in environmental advocacy. Jean-Michel Cousteau has become a prominent environmental educator through his Ocean Futures Society, while his son Fabien continues developing new underwater habitats and exploration technologies. Pierre-Yves Cousteau founded Cousteau Divers to engage recreational divers in conservation efforts. Even his granddaughter Céline has emerged as an influential ocean advocate, proving that the family's commitment to the seas spans generations.

This multigenerational impact creates a unique phenomenon in environmentalism - what experts call "The Cousteau Effect." Unlike other conservation movements that rely on institutions, the Cousteau legacy operates as both a scientific dynasty and a cultural force, blending exploration, media, and advocacy in ways no single organization could replicate.

Modern Scientific Validation of Cousteau's Warnings

Decades after his initial warnings, modern science has validated many of Cousteau's most urgent concerns. His early observations about coral bleaching, plastic pollution, and overfishing now form the basis of mainstream climate science. Researchers have confirmed that the ocean absorbs 30% of human-produced CO2 and 90% of excess heat from global warming, just as Cousteau predicted in his 1970s lectures.

Particularly prescient was his emphasis on the "hydrologic unity" principle - the understanding that all water systems on Earth are interconnected. Today's studies on microplastic distribution, chemical pollution dispersal, and current system alterations all reflect this foundational concept. Ocean acidification, a term barely used in Cousteau's time, has become a key climate change indicator directly linked to his early observations of changing marine ecosystems.

The Cousteau Paradox: Celebrity vs. Scientist

An ongoing debate surrounds Cousteau's dual identity as both rigorous scientist and media personality. Some marine biologists argue that his fame overshadowed his substantive contributions to oceanography. However, recent scholarship highlights how his showmanship actually advanced marine science by:

1) Securing funding for research during eras of limited academic support

2) Democratizing scientific knowledge through accessible media

3) Creating public pressure for marine protection policies

This "popular science" model has become standard practice among modern researchers like National Geographic's Enric Sala or BBC's Chris Packham, proving Cousteau's approach was ahead of its time.

Cousteau's Technologies in the 21st Century

The Aqua-Lung revolutionized diving, but it was just one of Cousteau's 32 patented inventions. Modern diving equipment still uses principles from his original designs, while his underwater camera housings became the blueprint for today's marine filming technology. The SP-350 "diving saucer" submersible, developed in 1959, foreshadowed modern underwater drones and remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) used in deep-sea exploration.

Perhaps most visionary was his 1965 Conshelf experiment, where aquanauts lived in an underwater habitat for weeks. While the program ended in the 70s, NASA now uses similar protocols for astronaut training, and private firms like OceanGate cite Cousteau as inspiration for their underwater habitation research. His proposed "oceanographic buoy" network presaged today's sophisticated ocean monitoring systems that track everything from temperature shifts to marine migrations.

Posthumous Honors and Cultural Permanence

Cousteau's cultural imprint remains strong years after his death. The 2016 documentary Becoming Cousteau reintroduced his legacy to new generations, while exhibitions at the Smithsonian and Musée de la Marine continue drawing crowds. Google honored him with a Doodle on his 100th birthday, and his image appears on everything from UNESCO medals to French postage stamps.

Academic institutions have established Cousteau chairs in marine science, while environmental groups frequently invoke his name in campaigns. This enduring relevance suggests his impact transcends mere nostalgia - Cousteau created a permanent framework for how society engages with the marine world.

The Future of Cousteau's Vision

Looking forward, Cousteau's principles could guide emerging ocean challenges. His emphasis on international cooperation anticipates current debates over deep-sea mining regulation. His warnings about technology's dual potential (to both exploit and protect) inform ethical discussions about geoengineering solutions for coral reefs. Even his early work documenting underwater noise pollution predates today's research on how ship traffic affects marine mammals.

Perhaps most crucially, Cousteau's human-centered storytelling provides a model for communicating climate science. Modern researchers increasingly adopt his narrative techniques to make complex marine issues relatable, understanding - as he did - that facts alone rarely inspire action.

Jacques Cousteau's ultimate legacy may be this: he transformed humanity's relationship with the sea from one of conquest to stewardship, proving that wonder and wisdom can coexist in our exploration of Earth's final frontier. The oceans he loved now face unprecedented threats, but the tools he created - both technological and philosophical - continue to equip new generations to protect them.

The Enchanting World of Forests

Introduction to Forests

Forests are among the most vital ecosystems on our planet, covering approximately 31% of the Earth's land area. They are home to an incredible diversity of flora and fauna, playing a crucial role in maintaining the balance of nature. Forests act as the lungs of the Earth, absorbing carbon dioxide and releasing oxygen, making them indispensable for human survival. Beyond their ecological importance, forests offer a sanctuary for adventure, tranquility, and inspiration.

From the dense rainforests of the Amazon to the towering pine forests of Scandinavia, each forest type has its unique characteristics and inhabitants. Whether you're a nature lover, a scientist, or simply someone seeking solace, forests have something to offer everyone. In this article, we will explore the wonders of forests, their significance, and the magic they hold within their green canopies.

The Different Types of Forests

Tropical Rainforests

Tropical rainforests are located near the equator and are characterized by high rainfall and consistent warm temperatures. These forests are biodiversity hotspots, housing more than half of the world's plant and animal species. The dense vegetation and layered canopy create a unique ecosystem where life thrives at every level. From colorful birds like toucans and parrots to elusive big cats like jaguars, tropical rainforests are teeming with life.

Deforestation poses a significant threat to these ecosystems, with vast areas being cleared for agriculture, logging, and urban expansion. Conservation efforts are crucial to preserving these vital habitats and the species that depend on them.

Temperate Forests

Temperate forests are found in regions with distinct seasons, including North America, Europe, and parts of Asia. These forests experience moderate temperatures and rainfall, supporting a mix of deciduous and coniferous trees. In autumn, the foliage of deciduous trees turns vibrant shades of red, orange, and yellow, creating breathtaking landscapes.

Wildlife in temperate forests includes deer, bears, foxes, and a variety of bird species. These forests also provide valuable resources such as timber and medicinal plants, making them economically important as well.

Boreal Forests (Taiga)

The boreal forest, or taiga, is the largest terrestrial biome, stretching across North America, Europe, and Asia. These forests are dominated by coniferous trees like spruce, pine, and fir, which are adapted to cold climates and short growing seasons. The taiga plays a critical role in regulating the Earth's climate by storing vast amounts of carbon in its soils and vegetation.

Wildlife in the boreal forest includes moose, wolves, lynx, and migratory birds. Despite the harsh winters, these forests are vital for global biodiversity and carbon sequestration.

The Importance of Forests

Ecological Benefits

Forests are essential for maintaining ecological balance. They help regulate the climate by absorbing carbon dioxide, a major greenhouse gas, and releasing oxygen through photosynthesis. Forests also play a key role in the water cycle, absorbing rainfall and reducing the risk of floods and soil erosion.

Moreover, forests provide habitat for countless species, many of which are endangered or endemic to specific regions. The loss of forests can lead to habitat destruction and the extinction of species, disrupting entire ecosystems.

Economic Benefits

Forests contribute significantly to the global economy. They provide raw materials for industries such as timber, paper, and pharmaceuticals. Many communities rely on forests for their livelihoods, whether through logging, tourism, or gathering non-timber forest products like fruits, nuts, and medicinal plants.

Sustainable forest management is essential to ensure these resources are available for future generations while minimizing environmental impacts.

Cultural and Spiritual Significance

Forests have deep cultural and spiritual significance for many indigenous and local communities. They are often considered sacred and are central to traditional practices, rituals, and folklore. Forests also inspire art, literature, and music, serving as a muse for creativity and reflection.

For many people, forests offer a place of peace and rejuvenation, where they can reconnect with nature and escape the stresses of modern life.

Threats to Forests

Deforestation

Deforestation is one of the greatest threats to forests worldwide. Large-scale clearing of forests for agriculture, logging, and urban development has led to habitat loss, climate change, and biodiversity decline. The Amazon rainforest, often referred to as the "lungs of the Earth," is experiencing rapid deforestation, with devastating consequences for global ecosystems.

Efforts to combat deforestation include reforestation projects, sustainable land-use practices, and policies to protect vulnerable areas.

Climate Change

Climate change is altering forest ecosystems in profound ways. Rising temperatures, changing precipitation patterns, and increased frequency of wildfires are impacting forest health. Some species may struggle to adapt, leading to shifts in forest composition and function.

Forests also play a dual role in climate change—they act as carbon sinks but can become carbon sources if degraded or destroyed.

Pollution and Invasive Species

Air and water pollution can harm forest ecosystems, affecting soil quality and plant health. Invasive species, introduced by human activities, can outcompete native flora and fauna, disrupting ecological balance. For example, invasive insects like the emerald ash borer have devastated ash tree populations in North America.

Protecting forests from these threats requires global cooperation and proactive conservation measures.

Conclusion of Part One

Forests are not just collections of trees; they are complex, life-sustaining ecosystems that benefit humans and the planet in countless ways. From their ecological and economic importance to their cultural and spiritual value, forests are irreplaceable. However, they face numerous threats that require immediate attention and action.

In the next part of this article, we will delve deeper into the unique flora and fauna of forests, exploring the intricate relationships that sustain these ecosystems. Stay tuned to uncover more about the enchanting world of forests.

The Flora and Fauna of Forests

The Lush Plant Life

Forests host an astonishing variety of plant species, each adapted to thrive in specific conditions. In tropical rainforests, towering emergent trees rise above the dense canopy, reaching heights of over 200 feet. Below them, a middle layer of smaller trees forms a continuous green roof, while the forest floor remains shrouded in relative darkness, nurturing shade-tolerant plants like ferns and mosses.

Epiphytes, or air plants, create vertical gardens on tree branches in these humid environments. Orchids, bromeliads, and ferns grow without soil, extracting nutrients from the air and rainwater. Some plant species have evolved remarkable symbiotic relationships with animals for pollination - the corpse flower attracts beetles with its rotting flesh scent, while the chocolate tree depends exclusively on tiny midges.

Temperate forests feature deciduous trees like oaks and maples that undergo dramatic seasonal changes. Their leaves contain chlorophyll in spring and summer, then reveal vibrant pigments as chlorophyll breaks down in autumn. The forest floor erupts with wildflowers in spring, taking advantage of sunlight before the canopy fills in.

Remarkable Forest Adaptations

Forest plants have developed ingenious survival strategies. Some tropical trees grow buttress roots as wide as the tree itself for stability in shallow soils. The strangler fig begins life as a seed deposited in a tree's branches, eventually enveloping its host in a living cage of roots. Certain bamboo species can grow up to 35 inches in a single day, making them the fastest-growing plants on Earth.

Many forest plants produce chemical defenses against herbivores. The black walnut tree releases juglone, a substance toxic to many other plants, creating a zone where few species can grow beneath it. Some tropical vines contain compounds now being studied for potential cancer treatments.

Forest Wildlife Ecosystems

Mammals of the Forest

Forests provide homes for mammals of all sizes, from tiny shrews to massive elephants. The Amazon rainforest alone contains over 400 mammal species. Primates are particularly diverse in tropical forests, with orangutans in Asia swinging through the canopy and howler monkeys making their presence known with deafening calls in Central and South America.

Large predators help maintain ecosystem balance. Tigers in Asian forests, jaguars in South America, and wolves in northern forests regulate prey populations. Many mammals have developed specialized forest adaptations - flying squirrels glide between trees using skin flaps, while okapis in African rainforests use their long tongues to strip leaves from branches.

Forest Birds and Their Songs

Forests echo with bird calls, from the haunting hoots of owls to the melodious songs of warblers. Tropical forests boast the greatest avian diversity, with colorful toucans, macaws, and birds of paradise. The harpy eagle, one of the world's most powerful raptors, hunts monkeys and sloths in the rainforest canopy.

Many forest birds play crucial ecological roles. Hornbills in Asia and Africa spread seeds through their droppings, while woodpeckers create cavities that later shelter other animals. The endangered kākāpō, a flightless parrot from New Zealand, was saved from extinction through intensive conservation efforts in its forest habitat.

Insect Life in the Understory

Insects form the foundation of forest food chains. Leafcutter ants in South American forests cultivate fungal gardens, carrying leaf fragments many times their weight. Fireflies create magical light displays in temperate forests at dusk, using bioluminescence to attract mates. The giant Asian honey bee builds enormous nests suspended from forest trees, each containing thousands of individuals.

Some insects have extraordinary relationships with plants. The fig wasp pollinates fig trees in a complex life cycle where tree and insect depend completely on each other. Certain Amazonian butterflies gather at clay licks to absorb minerals unavailable from nectar alone.

Microscopic Forest Worlds

Fungi: The Forest's Hidden Network

Beneath the forest floor lies a vast fungal network connecting trees in a "wood wide web." Mycorrhizal fungi form symbiotic relationships with tree roots, exchanging nutrients for sugars. Some research suggests trees may use these networks to communicate, sending chemical warnings about pests or drought.

Fungi play crucial decomposition roles. Oyster mushrooms produce enzymes that can break down oil and plastic pollutants, while some species attack living trees, causing devastating forest diseases. The honey fungus, spreading through root systems, holds the record as Earth's largest organism - one specimen in Oregon covers 2,400 acres.

Soil Microorganisms

A teaspoon of forest soil may contain billions of microorganisms. Nitrogen-fixing bacteria convert atmospheric nitrogen into forms plants can use, while protozoa and nematodes regulate microbial populations. These microscopic organisms maintain soil structure and fertility, allowing forests to regenerate after disturbances.

Some bacteria form unusual partnerships. In Central American cloud forests, bacteria inside leafhoppers allow the insects to feed exclusively on tree sap by producing essential amino acids the sap lacks.

Forest Adaptations to Climate

Tropical Forest Water Cycles

Rainforests create their own weather through transpiration. A single large tree can release hundreds of gallons of water into the atmosphere daily. This moisture forms clouds and generates rainfall that sustains the forest ecosystem. Deforestation disrupts this cycle, potentially converting lush forests into dry savannas.

Boreal Forest Winter Survival

Taiga species employ remarkable winter adaptations. Snowshoe hares grow white winter coats for camouflage, while lynx develop furred paws acting as natural snowshoes. Coniferous trees have needle-like leaves resistant to freezing, and their downward-sloping branches shed heavy snow loads.

Scientific Discoveries in Forests

Medical Breakthroughs

Forests continue yielding medical wonders. The rosy periwinkle from Madagascar rainforests produces compounds used in childhood leukemia treatments. Scientists recently discovered bacteria in Borneo's forests that produce an antibiotic effective against resistant superbugs. Over 25% of modern medicines originate from rainforest plants.

Technological Inspirations

Forest adaptations inspire human innovation. The structure of banyan tree roots influenced earthquake-resistant building designs. Scientists are developing synthetic materials mimicking lotus leaves' water-repellent properties, originally observed in floodplain forests.

Conclusion of Part Two

The intricate web of forest life reveals nature's incredible complexity and resilience. From towering trees to microscopic organisms, each component plays a vital role in maintaining these ecosystems. As we continue to uncover forest secrets, our responsibility to protect these natural wonders grows ever clearer.

In the final part of this article, we will explore human relationships with forests, including conservation efforts, sustainable practices, and the future of these precious ecosystems worldwide.

Human Relationships with Forests Through History

Ancient Connections

For thousands of years, forests have shaped human civilization while humans have shaped forests. Early humans found shelter among ancient trees, harvested medicinal plants, and hunted forest game. Sacred groves appeared across cultures - from the druid sites of Celtic Europe to the deodar forests revered in Himalayan traditions. Many indigenous creation myths feature forest spirits or tree deities, reflecting humanity's deep-rooted connection to woodland ecosystems.

The Age of Exploration and Exploitation

The colonial era marked a turning point in forest use. Shipbuilding consumed massive quantities of old-growth timber, particularly oak and teak. The industrial revolution accelerated deforestation as railroads expanded and cities grew. By the late 19th century, concerns about timber shortages sparked the first conservation movements. Pioneering foresters like Gifford Pinchot in America and Dietrich Brandis in India developed sustainable harvesting techniques that balanced economic needs with regeneration.

Modern Conservation Efforts

Protected Area Networks

Today, about 15% of the world's forests lie within protected areas. UNESCO World Heritage Sites like Indonesia's Tropical Rainforest Heritage of Sumatra and Canada's Wood Buffalo National Park safeguard critical habitats. Biosphere reserves combine protection with sustainable use, creating buffer zones where local communities can harvest forest products responsibly. New technologies like satellite monitoring and acoustic sensors help patrol vast protected areas.

Reforestation Initiatives

Ambitious global projects aim to restore degraded forests. China's Great Green Wall seeks to halt desertification by planting trees along the Gobi Desert's edge. In Africa, the Great Green Wall initiative stretches across the Sahel region. Innovative approaches include using seed-dispersing drones in Brazil and employing Indigenous fire management techniques in Australia. Costa Rica reversed deforestation through payments for ecosystem services, increasing forest cover from 21% to over 50% since the 1980s.

Indigenous Forest Stewardship

Traditional Ecological Knowledge

Indigenous communities manage about 28% of the world's land surface, including some of the healthiest remaining forests. Their practices demonstrate remarkable sustainability - the Kayapó people of Brazil selectively harvest Brazil nuts while maintaining the forest canopy. In Borneo, Dayak communities practice rotational farming that mimics natural succession. Researchers increasingly recognize that Indigenous land management supports higher biodiversity than conventional protected areas.

Legal Recognition of Rights

The 2007 UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples affirmed land rights, leading to expanding territories under Indigenous control. Canada's Haida Gwaii archipelago and New Zealand's Te Urewera forest now operate under Indigenous governance. Studies show these community-managed forests experience lower deforestation rates while providing livelihoods. However, many Indigenous protectors face threats from illegal loggers and land grabbers.

Sustainable Forestry Practices

Certification Systems

The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) and Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC) monitor sustainable timber production. Certified operations must maintain biodiversity, protect water quality, and respect workers' rights. Some enterprises go further - in Sweden, forest companies leave 5-10% of trees standing as habitat corridors. Agroforestry systems combine tree cultivation with crops like coffee or cacao, providing shade while preventing soil erosion.

Urban Forestry Innovations

Cities worldwide are embracing forests within their boundaries. Singapore's "City in a Garden" vision incorporates vertical gardens and nature reserves covering nearly 10% of its area. Milan's Bosco Verticale towers host 800 trees on their façades. Urban trees reduce the heat island effect, with mature specimens absorbing up to 150kg of CO2 annually. Community forests in places like Portland, Oregon demonstrate how cities can integrate nature with urban living.

Forests in a Changing Climate

The Carbon Storage Dilemma

Forests currently absorb about 30% of human-caused CO2 emissions, but climate change threatens this service. Warmer temperatures increase wildfire risks while insect outbreaks kill millions of trees. Scientists debate whether to prioritize planting fast-growing species for carbon capture or native trees supporting biodiversity. The Trillion Trees Initiative combines both approaches, aiming to restore forests globally while creating conservation jobs.

Assisted Migration Controversy

As climatic zones shift, conservationists consider relocating tree species to more suitable areas. The whitebark pine, threatened by warming in the American West, might be transplanted northward. Opponents warn of unintended ecological consequences, preferring to enhance natural regeneration. Genetic engineering offers another approach - American chestnut trees modified for blight resistance may soon repopulate eastern forests.

Ecotherapy and Forest Bathing

The Science of Nature Therapy

Japanese researchers pioneered shinrin-yoku (forest bathing), demonstrating that phytoncides from trees boost human immune function. Studies show spending time in forests lowers cortisol levels, reduces blood pressure, and improves mental health. Some hospitals now incorporate "healing gardens" where patients recover surrounded by nature. Outdoor kindergartens in Scandinavia report children develop stronger immune systems and better concentration.

Forest Retreats Worldwide

From Buddhist forest monasteries in Thailand to eco-lodges in Costa Rica, retreat centers help people reconnect with nature. The growing "rewilding" movement encourages immersive nature experiences as antidotes to digital overload. Adventure therapy programs use wilderness treks to treat PTSD and addiction. Even virtual forest environments show promise for urban dwellers without access to real woodlands.

The Future of Forests

Emerging Technologies

Artificial intelligence helps monitor illegal logging through sound recognition systems that detect chainsaws. Blockchain enables transparent timber tracking from forest to consumer. Drones plant seeds and map deforestation in real time. Scientists are developing "smart forests" with sensors monitoring tree health, while synthetic biology may create plants that grow faster or resist diseases better.

Policy and Economic Shifts

Carbon markets now value standing forests, with countries like Norway paying tropical nations to reduce deforestation. The concept of "natural capital" quantifies ecosystem services in economic terms. Some economists propose redirecting harmful subsidies toward forest conservation. Youth-led movements push for stronger protections, with lawsuits establishing legal rights for nature in countries like Ecuador.

Personal Action and Hope

Every individual can contribute to forest conservation. Choosing FSC-certified products, reducing paper use, and supporting conservation organizations all make an impact. Ecotourism provides sustainable income for forest communities. Planting native trees, even in urban yards, creates wildlife corridors. Most importantly, sharing forest experiences with children nurtures the next generation of environmental stewards.

A Call to Conservation

Forests stand at a crossroads - their future depends on choices we make today. These ancient ecosystems have survived ice ages and continental shifts, yet human impacts now threaten their existence. The solutions exist: blending traditional knowledge with modern science, balancing use with protection, and recognizing forests as living systems rather than mere resources.

From the whispering pines of northern taiga to the cacophonous diversity of tropical canopies, forests remind us of nature's resilience and interconnectedness. As John Muir observed, "In every walk with nature one receives far more than he seeks." May we honor this gift by ensuring forests continue thriving for all life that depends on them - including our own.