Understanding the Power of Trial and Error

Have you ever tried something that didn't work out quite right, only to keep trying until you finally hit the mark? If so, congratulations! You've just done trial and error. It's a technique that's been around since the dawn of time, helping us learn from our mistakes and find solutions for problems. Whether you're a student figuring out how to solve a tricky math problem or an entrepreneur trying to figure out what makes your business tick, trial and error plays a crucial role.

In simplest terms, trial and error is a problem-solving approach where you test different methods and ideas to see which one works. Unlike the more conventional methods that focus on planning and theory before taking action, trial and error relies on practical experimentation and real-world feedback. This approach might seem simple on the surface, but it's incredibly powerful in the realm of learning and problem-solving.

The Basics of Trial and Error

Let's dive into some key facts and recent developments related to trial and error. First things first, it's important to understand what exactly we mean by this term. According to various sources, trial and error involves making repeated attempts to solve a problem, each time learning from any failures that you encounter. These failures are not seen as setbacks but rather as valuable data points that help guide you closer to a successful outcome.

Versatile Application Across Fields

One of the remarkable aspects of trial and error is its versatility. It's not confined to any single field—it's used all over the place! Here are a few examples:

- Entrepreneurship: Entrepreneurs often rely heavily on trial and error to test their ideas and strategies without incurring heavy financial costs. By making small investments that pay off if successful and learning from failures, they can refine their products or services and find the right market fit.

- Scientific Experiments: Scientists use trial and error to test hypotheses and theories. They perform experiments, analyze results, and adjust their methods based on what they learn, leading to breakthroughs and discoveries.

- Everyday Problem-Solving: We all have faced situations like trying multiple passwords until we find the right one or figuring out how to assemble a new toy. These are everyday instances of trial and error at work—learning as you go and improving with each attempt.

Historical Importance and Empirical Learning

While trial and error might seem like a relatively recent development, it’s actually one of the oldest and most fundamental learning methods known to both humans and animals. It serves as a cornerstone for how we learn from experience. Unlike purely theoretical methods that rely on logic and deduction, trial and error is rooted in the practical observation and experimentation.

Empirical Approach to Problem-Solving

So, what exactly is an empirical approach? Simply put, it means relying on observation and experiment to gather information and make decisions. In contrast to theories that might work well on paper but fail in practice, trial and error allows us to see what really works through direct experience. By going through the process of attempting something, observing the results, and then adapting our approach based on what happens, we can develop a deeper understanding of the situation.

Learning Through Mistakes

The beauty of trial and error lies in the fact that it teaches us more effectively than purely theoretical learning. When you make a mistake, instead of ignoring it or feeling discouraged, you can use that information to do better next time. This doesn’t just apply to technical skills or academic knowledge—it applies to life in general. Whether you’re learning to cook a new dish, teach a pet a trick, or manage finances, trial and error helps you become more resilient and adaptable.

Critical Thinking and Resilience

Trial and error isn’t just about solving problems; it's also about enhancing critical thinking skills. Each failed attempt is an opportunity to think critically about what went wrong and how you can adjust your approach. This process encourages creativity and innovation by pushing us out of our comfort zones and forcing us to explore new possibilities.

Rather than fearing failure, people who use trial and error embrace it as an essential part of the journey. They understand that every failed attempt brings them closer to success, allowing them to build resilience and a growth mindset. This way of thinking helps them to stay motivated even when the path ahead seems unclear, knowing that persistent effort will eventually lead to positive outcomes.

Incorporating Technology

Modern technology has revolutionized the way we practice trial and error. Tools like computer simulations and artificial intelligence allow us to run numerous experiments quickly and efficiently. These digital platforms provide instant feedback and data analysis, making it easier to identify patterns and refine our methods. As a result, trial and error cycles have become much faster, enabling rapid learning and innovation.

Furthermore, online resources and communities offer vast libraries of examples and advice for anyone looking to improve their skills. Platforms such as YouTube tutorials, online forums, and educational apps are filled with tips and tricks from experts and enthusiasts alike. Leveraging these resources can significantly enhance our problem-solving abilities by showing us proven techniques and avoiding common pitfalls.

The Future of Trial and Error

So, what does the future hold for trial and error? While it remains a cornerstone of learning and innovation, it's likely to evolve alongside advancements in technology. New AI tools, for instance, could automate much of the trial phase, leaving humans to interpret outcomes and make strategic decisions.

In addition, educators are increasingly recognizing the value of experiential learning methods like trial and error. By providing students with hands-on opportunities to explore and fail, they can develop a stronger grasp of concepts and better prepare for real-world challenges. Schools are incorporating more project-based learning and hands-on activities, fostering an environment where students can confidently embrace their mistakes as stepping stones towards success.

Finding Success Through Iteration

In the end, success in almost any endeavor often comes from a combination of persistence, creativity, and the willingness to accept failure as part of the learning process. Trial and error is a valuable tool that can help us navigate complex and unpredictable situations, teaching us valuable lessons along the way. So, the next time you face a challenge, remember: it’s okay to try something and not succeed at first. Embrace the process, learn from your mistakes, and keep trying until you reach your goal. That’s the true spirit of trial and error!

New Frontiers in Education and Beyond

The application of trial and error extends far beyond entrepreneurship, scientific research, and everyday problem-solving. Its impact is particularly evident in the realm of education, especially in today's rapidly changing world. Educational institutions are increasingly adopting experiential learning methods to foster critical thinking, innovation, and resilience among young learners. These approaches not only enhance academic performance but also prepare students for real-world challenges by equipping them with practical skills and a growth mindset.

Youth-Led Innovation

One striking example of this shift is seen in the growing number of youth-led initiatives and hackathons. Young individuals are using trial and error to come up with innovative solutions to pressing global issues like climate change, social injustice, and technological advancements. Through these events, they collaborate, brainstorm, and test their ideas, learning from feedback and refining their projects. For instance, many students participate in hackathons, building prototypes of technology gadgets or software applications that address specific problems.

These experiences not only provide hands-on learning but also instill confidence and a sense of agency in young learners. By actively participating in the problem-solving process, they develop a deep understanding of the subject matter and gain invaluable skills such as teamwork, creative thinking, and project management. Moreover, such activities often involve mentorship from older professionals and access to resources that would otherwise be out of reach, further enriching the learning experience.

Real-World Application in Curriculum

Incorporating trial and error into the curriculum involves moving away from traditional lecture-based methods and towards more interactive and participatory forms of learning. Teachers are designing lessons that encourage students to engage in real-world problem-solving tasks. For instance, in mathematics classes, students might be given open-ended problems and asked to explore multiple methods to arrive at a solution. Similarly, science classes can involve experimental design projects where students hypothesize, conduct tests, and analyze data, all while receiving guidance and support from instructors.

Another effective strategy is project-based learning, where students work on long-term projects that require them to apply their knowledge and skills in creative and meaningful ways. These projects often involve collaboration with peers and can span multiple subjects, allowing students to see the interconnectedness of different areas of study. For example, a biology project might involve researching local ecosystems, collecting data, and presenting findings to the class, all while developing critical thinking skills.

Digital Tools Facilitating Faster Learning Cycles

The integration of digital tools and simulations has also greatly accelerated the trial and error process. Platforms like CodeLab and Google's Teachable Machine allow students to quickly develop and test code or machine learning models. These tools provide instant feedback, enabling students to iterate on their designs more efficiently. For instance, a user might create a simple game using Scratch and continuously adjust the code to improve gameplay mechanics, all within a few minutes.

Similarly, virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) technologies offer immersive learning environments where students can experiment with complex systems without real-world risks. For example, medical students can practice surgical procedures in VR, or engineers can simulate robotic movements and design improvements. These technologies not only make learning more engaging but also provide a safe space for students to make mistakes and learn from them.

Encouraging Failure and Learning

To fully embrace the power of trial and error, it's crucial to create a culture that values and encourages failure. This means shifting the narrative from seeing mistakes as negative to viewing them as valuable learning opportunities. Educators should emphasize the importance of resilience and persistence, reinforcing the message that it's okay to stumble and that every failure brings us one step closer to success.

Classroom settings should be designed to foster a growth mindset—where students are encouraged to view challenges as opportunities for growth rather than obstacles to avoid. This can be achieved through various strategies, such as regular reflection sessions where students discuss what they learned from their mistakes, or group activities that promote collective problem-solving and peer support. By normalizing failure, students become more comfortable taking risks and pushing their boundaries, ultimately leading to greater overall success.

Combining Methods for Optimal Results

While trial and error is a powerful tool, combining it with other problem-solving strategies can yield even better results. Integrating trial and error with techniques like design thinking, where students follow a structured process of empathy, ideation, prototyping, and testing, can lead to more innovative and sustainable solutions. For example, a design thinking project might involve students conducting user interviews to understand needs, brainstorming solutions collectively, creating prototypes, and then testing and refining these solutions through iterative cycles of trial and error.

Similarly, combining trial and error with the scientific method can result in more robust research and development. By systematically testing hypotheses and analyzing data, students can develop a deeper understanding of the underlying processes and principles. This hybrid approach ensures that both creativity and rigor are maintained throughout the problem-solving process.

Conclusion

In conclusion, trial and error is a versatile and essential problem-solving technique that has stood the test of time. Its applications range from everyday problem-solving to cutting-edge scientific research and entrepreneurial ventures. As technology continues to advance, trial and error becomes faster and more efficient, making it a valuable tool for a wide array of industries and individuals.

The future of this approach lies in its seamless integration with other learning and problem-solving methods. By embracing this method and fostering a culture of resilience and continuous improvement, we can prepare ourselves and future generations to face and overcome whatever challenges may come our way. So remember, every mistake is a step towards success. Embrace trial and error, learn from it, and keep pushing forward!

Fostering a Culture of Learning from Mistakes

Creating a culture of learning from mistakes is crucial for truly harnessing the power of trial and error. In schools and workplaces, leaders play a pivotal role in establishing an environment where failure is not shunned but embraced as a stepping stone to growth. This involves several key practices:

- Open Discourse: Encouraging open discussions about failures and successes can break down the stigma associated with mistakes. By sharing stories of past failures and the lessons learned, individuals feel less alone and more supported. Teachers and managers can facilitate these discussions to highlight how mistakes contributed to eventual success.

- Constructive Feedback: Providing constructive feedback is essential to help those involved understand why a particular approach did not work and how it can be improved next time. This feedback should focus on actionable steps to move forward rather than placing blame.

- Continuous Improvement: Establishing a continuous improvement mindset means constantly seeking ways to refine processes and strategies. By regularly reviewing outcomes and reflecting on what worked and what didn't, organizations and individuals can make incremental adjustments that lead to better overall performance.

Personal Growth Through Trial and Error

Trials and errors do not only benefit professional careers but also contribute to personal growth. Whether tackling a difficult puzzle or trying a new hobby, the process of trial and error cultivates a variety of skills and traits:

- Problem-Solving Skills: Engaging in trial and error helps develop strong problem-solving skills. Individuals learn to break down complex issues into manageable parts, test various hypotheses, and adapt strategies based on feedback.

- Resilience: Repeated experiences of trying something and failing can build resilience. Over time, individuals develop the mental toughness to face challenges head-on and persist even when faced with setbacks.

- Adaptability: The flexibility to pivot and try a new approach when the old one fails fosters adaptability. This skill is crucial in rapidly changing environments where traditional methods may no longer be effective.

- Growth Mindset: Recognizing that intelligence and abilities can grow with effort and practice promotes a growth mindset. This mindset encourages individuals to see failures as temporary setbacks that can be overcome with hard work and determination.

Addressing Criticism and Misconceptions

Some might argue that trial and error can be inefficient or costly. However, the cost of not trying at all is often much higher. Consider the example of an aspiring musician who fears playing an instrument in public due to the risk of failure. While making mistakes publicly can be embarrassing, not taking those risks prevents the musician from improving and potentially achieving great success in the future.

Misconceptions about trial and error often stem from a focus on immediate success rather than the long-term benefits. While it might take several attempts to get something right, each failure provides valuable data and insights that contribute to eventual mastery. In entrepreneurship, for instance, many startups undergo multiple pivot moments before finding a viable business model. These pivots are rarely linear and often involve numerous trials before they hit upon the right direction.

Conclusion

In summary, trial and error is a fundamental tool for learning and innovation that transcends fields and personal endeavors. By embracing this method, we cultivate problem-solving skills, build resilience, and foster a growth mindset. Whether you're a student, entrepreneur, scientist, or just someone facing everyday challenges, adopting a spirit of trial and error can propel you forward toward success.

As we look to the future, let us not only recognize the importance of trial and error but also nurture a community that values and supports it. By doing so, we empower individuals and organizations to innovate, persist, and thrive in an ever-changing world.

Remember, the next time you face a challenge, don't be afraid to give it a try. Every failure brings you closer to success. Embrace trial and error, learn from every step, and continue moving forward with determination and resilience.

Luigi Galvani: The Father of Modern Neurophysiology

Luigi Galvani, an Italian physician and physicist, revolutionized our understanding of nerve and muscle function. His pioneering work in the late 18th century established the foundation of electrophysiology. Galvani’s discovery of animal electricity transformed biological science and remains central to modern neuroscience.

Early Life and Scientific Context

Birth and Education

Born in 1737 in Bologna, Italy, Galvani studied medicine at the University of Bologna. He later became a professor of anatomy and physiology, blending rigorous experimentation with deep curiosity about life processes. His work unfolded during intense scientific debates about nerve function.

The Debate Over Nerve Function

In the 1700s, two theories dominated: neuroelectric theory (nerves use electricity) and irritability theory (intrinsic tissue force). Galvani entered this debate with unconventional methods, usingfrogs to explore bioelectricity. His approach combined serendipity with systematic testing.

The Revolutionary Frog Leg Experiments

Galvani’s most famous experiments began in the 1780s. While dissecting a frog, he noticed leg muscles twitching near an electrostatic machine. This observation led him to hypothesis: animal electricity existed inherently in living tissues.

Key Experimental Breakthroughs

- Frog legs contracted when metallic tools touched nerves near electric sparks.

- He replicated contractions using copper-iron arcs, proving bioelectric forces didn’t require external electricity.

- Connecting nerves or nerve-to-muscle between frogs produced contractions, confirming intrinsic electrical activity.

“Nerves act as insulated conductors, storing and releasing electricity much like a Leyden jar.”

Publication and Theoretical Breakthroughs

In 1791, Galvani published “De Viribus Electricitatis in Motu Musculari Commentarius” (Commentary on the Effects of Electricity on Muscular Motion). This work rejected outdated “animal spirits” theories and proposed nerves as conductive pathways.

Distinguishing Bioelectricity

Galvani carefully differentiated animal electricity from natural electric eels or artificial static electricity. He viewed muscles and nerves as biological capacitors, anticipating modern concepts of ionic gradients and action potentials.

Legacy of Insight

His hypothesis that nerves were insulated conductors preceded the discovery of myelin sheaths by over 60 years. Galvani’s work laid groundwork for later milestones:

- Matteucci measured muscle currents in the 1840s.

- du Bois-Reymond recorded nerve action potentials in the same decade.

- Hodgkin and Huxley earned the 1952 Nobel Prize for ionic mechanism research.

Today, tools measuring millivolts in resting potential (-70mV) directly trace their origins to Galvani’s frog-leg experiments.

The Galvani-Volta Controversy

The Bimetallic Arc Debate

Galvani’s work sparked a fierce scientific rivalry with Alessandro Volta, a contemporary Italian physicist. Volta argued that the frog leg contractions resulted from bimetallic arcs creating current, not intrinsic bioelectricity. He demonstrated that connecting copper and zinc produced similar effects using frog tissue as an electrolyte.

While Volta’s critique highlighted external current generation, Galvani countered with nerve-to-nerve experiments. By connecting nerves between frogs without metal, he proved contractions occurred independent of bimetallic arcs, validating his theory of inherent animal electricity.

- Volta’s experiments focused on external current from metal combinations.

- Galvani’s nerve-nerve tests showed bioelectricity originated within tissues.

- Both scientists contributed critical insights to early bioelectricity research.

Resolving the Debate

Their争论 ultimately advanced electrophysiology. Volta’s findings led to the invention of the Voltaic Pile in 1800, the first electric battery. Galvani’s work confirmed living tissues generated measurable electrical signals. Modern science recognizes both contributions: tissues produce bioelectricity, while external circuits can influence it.

“Galvani discovered the spark of life; Volta uncovered the spark of technology.”

Impact on 19th Century Neuroscience

Pioneers Building on Galvani

Galvani’s ideas ignited a wave of 19th-century discoveries. Researchers used his methods to explore nerve and muscle function with greater precision. Key milestones include:

- Bernard Matteucci (1840s) measured electrical currents in muscle tissue.

- Emil du Bois-Reymond (1840s) identified action potentials in nerves.

- Carl Ludwig developed early physiological recording tools.

Technological Advancements

These pioneers refined Galvani’s techniques using improved instrumentation. They measured millivolt-level signals and mapped electrical activity across tissues. Their work transformed neuroscience from philosophical debate to quantitative science, setting the stage for modern electrophysiology.

Modern Applications and Legacy

Educational Revival

Today, Galvani’s experiments live on in educational labs. Platforms like Backyard Brains recreate his frog-leg and Volta battery demonstrations to teach students about neuroscience fundamentals. These hands-on activities demystify bioelectricity for new generations.

Universities worldwide incorporate Galvani’s methods into introductory neuroscience courses. By replicating his 18th-century techniques, learners grasp concepts like action potentials and ionic conduction firsthand.

Neurotechnology Inspired by Galvani

Galvani’s vision of nerves as electrical conductors directly influences modern neurotechnology. Innovations such as:

- Neural prosthetics that interface with peripheral nerves.

- Brain-computer interfaces translating neural signals into commands.

- Bioelectronic medicine using tiny devices to modulate organ function.

These technologies echo Galvani’s insight that bioelectricity underpins nervous system communication. His work remains a cornerstone of efforts to treat neurological disorders through electrical stimulation.

Historical Recognition and Legacy

Posthumous Acknowledgment

Though Galvani died in 1798, his work gained widespread recognition in the centuries that followed. The 1998 bicentenary of his key experiments sparked renewed scholarly interest, with papers reaffirming his role as the founder of electrophysiology. Modern historians credit him with shifting neuroscience from vague theories to measurable electrical mechanisms.

Academic journals continues to cite Galvani’s 1791 treatise in milestone studies, including Hodgkin-Huxley models that explain ionic mechanisms underlying nerve impulses. His name remains synonymous with the discovery that bioelectricity drives neural communication.

Monuments and Commemoration

Bologna, Italy, honors Galvani with statues, street names, and the Galvani Museum at the University of Bologna. The city also hosts an annual Galvani Lecture attended by leading neuroscientists. These tributes underscore his lasting impact on science and medicine.

- A bronze statue stands near Bologna’s anatomical theater.

- The Italian air force named a training ship “Luigi Galvani.”

- Numerous scientific awards bear his name.

Galvani’s Enduring Influence

Modern Recreations and Education

Galvani’s experiments remain classroom staples. Kits like Backyard Brains allow students to replicate his frog-leg and Volta battery demonstrations, bridging 18th-century discovery with 21st-century learning. These hands-on activities make abstract concepts like action potentials tangible.

Schools worldwide integrate Galvani’s work into curricula, emphasizing how serendipitous observation can lead to scientific breakthroughs. His story teaches the value of curiosity-driven research.

Advancements in Bioelectronics

Galvani’s vision of nerves as electrical conductors directly informs today’s neurotechnology. Innovations such as:

- Neural implants that restore sight or movement.

- Brain-computer interfaces for communication.

- Bioelectronic drugs that modulate organ function.

These technologies rely on the principle Galvani proved: living tissues generate and respond to electricity. His insights remain foundational to treating neurological disorders through electrical stimulation.

Quantitative Legacy

Galvani’s influence extends to precise measurement standards in neuroscience. Modern tools detect signals as small as millivolts, mapping resting potentials (-70mV) and action potentials (+30mV). These capabilities trace back to his frog-leg experiments, which first proved bioelectricity existed.

“Galvani gave us the language to speak to the nervous system—in volts and amperes.”

Conclusion

Summarizing Galvani’s Contributions

Luigi Galvani’s discovery of animal electricity reshaped our understanding of life itself. By proving nerves conduct electrical impulses, he laid the groundwork for:

- The field of electrophysiology.

- Modern neuroscience and neurotechnology.

- Quantitative approaches to studying the brain.

His work transcended 18th-century limitations, anticipating discoveries like myelin sheaths and ionic mechanisms by decades.

Final Key Takeaways

Galvani’s legacy endures in three critical areas:

- Scientific Foundation: He established nerves as biological conductors.

- Technological Inspiration: Modern devices mimic his principles.

- Educational Impact: His experiments teach generations about bioelectricity.

Luigi Galvani remains the father of modern neurophysiology not just for his discoveries, but for the enduring questions he inspired. Every time a neurologist monitors brain waves or an engineer designs a neural implant, they build on the spark Galvani first revealed. His work proves that sometimes, the smallest observation—a twitching frog leg—can illuminate the grandest truths about life.

Erwin Schrödinger: Mastering Quantum Theory and More

The Early Life and Academic Journey

The Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger, born on August 12, 1887, in Vienna, Austria, was one of the key figures in the development of quantum mechanics. Despite coming from a family with little formal scientific education, his early curiosity and intellectual prowess laid the groundwork for his later groundbreaking achievements. Schrödinger’s father, Rudolf Eugen Schrödinger, was a school inspector, while his mother, Karolina Ettersburger, came from a family of teachers and journalists, further influencing his academic inclinations.

Showcasing his talent from an early age, Schrödinger excelled academically, particularly in mathematics and physics. He graduated from high school in 1906 and went on to study mathematics at the University of Vienna. There, he was exposed to the intellectual rigor and dynamic research environment that would shape his future career.

Schroedinger's academic journey continued through his doctoral studies under Friedrich Hasenöhrl, a renowned theoretical physicist. Under Hasenöhrl's guidance, he developed a strong foundation in physics and mathematics. Schrödinger's early work focused on electrodynamics, where he showed great aptitude in solving complex problems and formulating mathematical models. His dissertation, submitted in 1910, was on the theory of special relativity and electromagnetic radiation, demonstrating his early genius in the field.

Contributions to Relativistic Electrodynamics

During his time as a university lecturer, Schrödinger continued his research into relativistic electrodynamics. His work in this area laid the foundations for what would later become a major focus of his career. In his 1916 paper "The Time-Dependent Representation of Wave Mechanics," Schrödinger introduced wave equations that described the motion of particles in a way that was consistent with both wave and particle theories, marking a significant shift in the understanding of quantum particles.

This research also led to the introduction of the concept of 'Schrödinger's equation,' a partial differential equation that describes how the quantum state of a physical system changes over time. While it was initially not widely recognized, his contributions to relativistic electrodynamics were crucial to the broader developments in quantum mechanics that followed.

The Concept of Wave Mechanics

In 1925, Schrödinger published a series of papers that would fundamentally transform the field of quantum mechanics. These papers, collectively known as the "Annalen der Physik" series, outlined his development of wave mechanics. Unlike Werner Heisenberg's matrix mechanics, Schrödinger's approach used a continuous wave picture to describe quantum states, which provided a more intuitive and visual representation for many physicists.

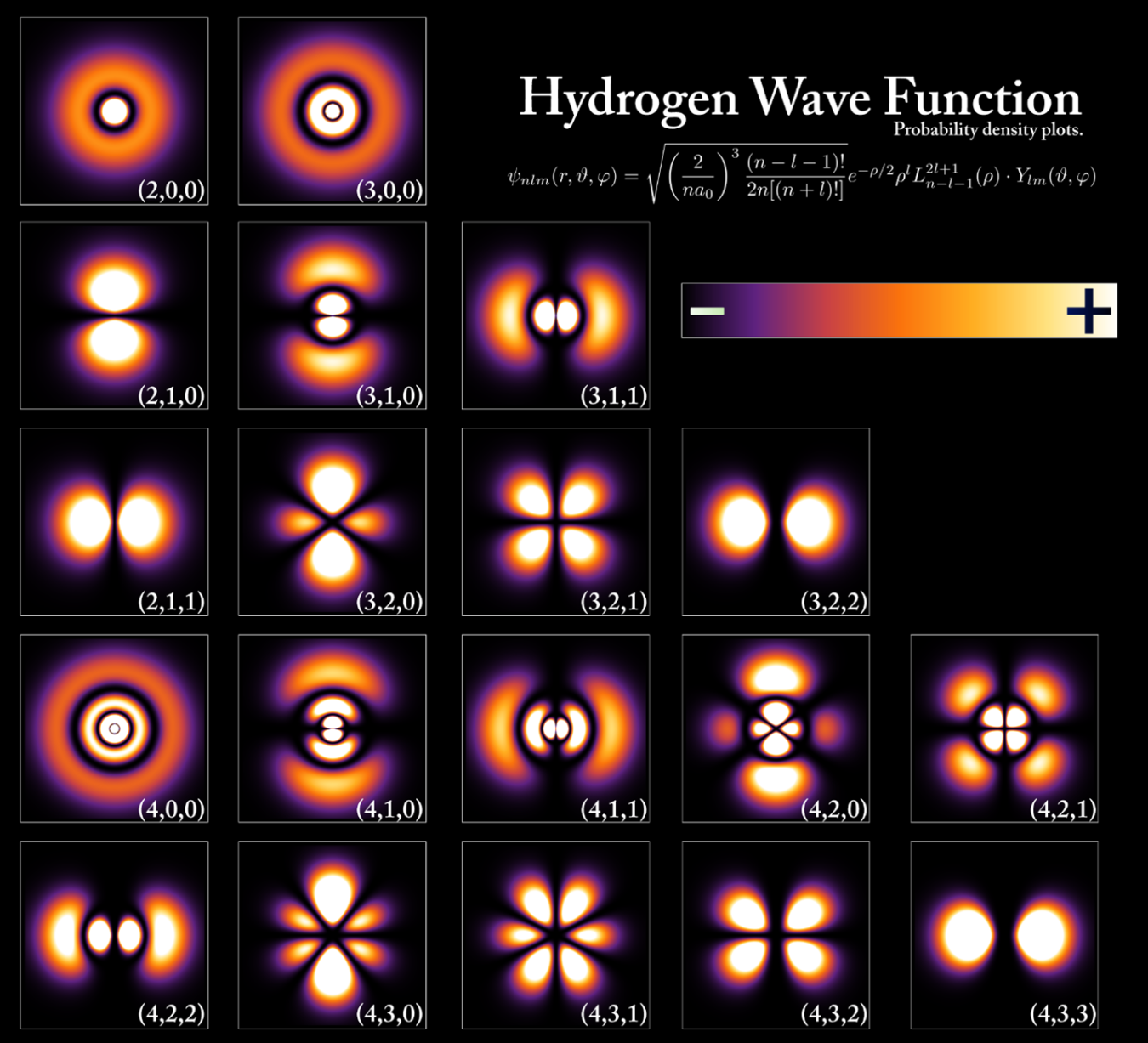

The concept of wave functions, denoted \(\psi\), became central to Schrödinger's work. A wave function is a mathematical description of the quantum state of a system, and its square (\(\psi^2\)) gives the probability density of finding a particle at a specific location. This interpretation of quantum mechanics provided a clearer, more visualizable framework compared to the more abstract matrix mechanics, and quickly gained popularity among many physicists.

A particularly notable application of wave mechanics came in the form of the Schrödinger equation, which describes how the quantum state of a physical system changes over time. Formally, the Schrödinger equation is given by:

\[i\hbar \frac{\partial}{\partial t}\psi = \hat{H}\psi\]

where \(i\) is the imaginary unit, \(\hbar\) is the reduced Planck constant, \(t\) is time, \(\psi\) is the wave function, and \(\hat{H}\) is the Hamiltonian operator representing the total energy of the system.

Schrodinger himself noted that his wave mechanics theory could not explain the fine structure of the hydrogen spectrum, which was accurately described by Heisenberg's matrix mechanics. However, his approach eventually led to the development of more advanced theories that reconciled these differences, thus solidifying his reputation as a pioneer in modern physics.

Other Scientific Contributions

Beyond his work in quantum mechanics, Schrödinger made noteworthy contributions to other fields of physics. He delved into biophysics, exploring the nature of life from a physical perspective. One of his most intriguing and provocative theories is the “What is Life?” lecture delivered in 1943, which proposed that the fundamental unit of biological organization could be explained via the statistical mechanics of macromolecules.

In 1944, Schrödinger published a book titled “What is Life?,” where he suggested that the genetic material of organisms could be based on simple physical laws. He hypothesized that living systems could be understood in terms of their thermodynamic properties, specifically the ability to maintain a stable internal environment (homeostasis), which contradicts the tendency in non-living systems toward increased entropy or disorder.

Another notable contribution was his collaboration with mathematician Herman Weyl on the geometry of space-time. Schrödinger applied Weyl's ideas to develop non-Riemannian geometries, which contributed to the development of general relativity. Although his work did not directly lead to new experimental results, it highlighted the potential of interdisciplinary approaches in theoretical physics.

The Famous Schrödinger's Cat Thought Experiment

No discussion of Erwin Schrödinger can be complete without mentioning his famous thought experiment, Schrödinger's Cat. Introduced in 1935 as part of a critique of quantum mechanics, the experiment posited a scenario where a cat confined within an opaque box could simultaneously be alive and dead if placed in a superposition state alongside a radioactive atom and a vial of poison gas.

The thought experiment challenges the intuitive notion that a system in the real world must exist in only one of its possible states at any given moment. According to quantum mechanics, until the box is opened and the state is observed, the cat could be in both states at once, a concept famously encapsulated in the phrase “Until a physicist looks inside the box to check the cat’s status, the cat is simultaneously alive and dead.”

This paradox raises profound questions about the interpretation of quantum mechanics and the nature of observation, leading to ongoing debates about the measurement problem in quantum physics. Schrödinger's cat became a powerful tool for illustrating the seemingly absurd implications of the superposition principle, sparking widespread interest and discussion in the scientific community.

The Later Years and Legacy

Despite his remarkable contributions to science and philosophy, Schrödinger experienced periods of personal struggle and controversy. His marriage to Annemarie Frankau dissolved in 1942, and he moved to Dublin to take up the position of Director of the Institute for Theoretical Physics at the School of Theoretical Physics, part of the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. Here, he conducted his famous experiments and thought experiments, contributing significantly to the evolution of modern physics.

In his later years, Schrödinger also engaged in philosophical discussions about the role of physics in the larger context of human knowledge and society. His works, such as “Mind and Matter” and “Nature and the Greeks,” delve into the relationship between physical laws and the nature of consciousness, challenging readers to consider deeper questions about the universe and our place within it.

Schrödinger remained active in his scientific pursuits until his death on January 4, 1961, in Vienna. His legacy endures in the formative theories and concepts named after him, such as Schrödinger's equation and Schrödinger's cat. These contributions have had a lasting impact on not only theoretical physics but also broader fields that explore the intersection between science and philosophy.

Influences on Schrödinger's Work and Personal Life

Schrodinger's academic career was influenced by a variety of factors, including his interactions with prominent scientists of his time. Albert Einstein, a fellow physicist whose work on relativity greatly influenced Schrodinger’s early research, was a lifelong friend and mentor. Their correspondence and collaborative efforts often focused on deepening and explaining the principles of quantum mechanics.

Throughout his life, Schrödinger maintained an active intellectual network that extended beyond physics. His conversations with philosophers like Bertrand Russell and Martin Heidegger played a significant role in shaping his views on the nature of reality and the relationship between science and philosophy. These debates helped Schrödinger formulate his thoughts on the inherent randomness and complexity of the natural world.

A Controversial Figure and Public Engagement

Erwin Schrödinger was not only a renowned scientist but also a public figure who engaged deeply with the broader implications of his work. His 1944 book, “What is Life?,” was a direct response to the philosophical inquiries of biologists and chemists during the early days of molecular biology. In this book, Schrödinger speculated on the nature of genetics and the possibility of information storage in cells, drawing parallels between the stability of life and the principles of quantum mechanics.

Despite his accolades, Schrödinger faced criticism and controversy throughout his career. His views on quantum mechanics sometimes diverged from those of the Copenhagen Interpretation, which was championed by Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg. This disagreement led to heated debates and, in some circles, Schrödinger was considered a renegade for challenging established doctrines. Nevertheless, his innovative approach to wave mechanics and his thought-provoking experiments, such as Schrödinger's cat, continue to fascinate and challenge scientists and philosophers alike.

Award and Recognition

Schrödinger received numerous awards and honors for his contributions to science. He was elected a corresponding member of the German Academy of Natural Sciences Leopoldina in 1926 and later became a full member in 1945. In 1933, he was awarded the Max Planck Medal by the German Physical Society, which recognized his significant contributions to theoretical physics. During World War II, he was appointed Commander of the Order of the White Eagle by the Nazis in 1940, a controversial honor due to his Jewish heritage and left-wing political views. After the war, he refused to accept the medal, symbolizing his opposition to the Nazi regime.

His contributions were so esteemed that in 1949, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics along with Paul Dirac. However, Schrödinger had passed away before the award ceremony; he died on January 4, 1961, shortly after his nomination. Nevertheless, the Nobel honor stands as a testament to his enduring influence on the field of quantum mechanics.

Legacy and Cultural Impact

The legacy of Erwin Schrödinger extends far beyond the technical advancements he made in physics. His thought experiments, such as Schrödinger's cat, have permeated popular culture, appearing in books, films, and television shows as a metaphor for uncertainty and unpredictability. This cultural impact underscores the universal appeal of his work and its relevance in contemporary discourse.

Moreover, Schrödinger’s philosophical writings have inspired numerous discussions on the relationship between science and ethics, particularly in the realms of genetics and environmental science. His work continues to be studied in academic circles, not just for its technical merit but also for its profound philosophical insights.

Conclusion

Erwin Schrödinger’s contributions to physics are immeasurable. From his early work on relativistic electrodynamics to his revolutionary theories in quantum mechanics, Schrödinger’s intellect and vision reshaped the landscape of modern physics. His legacy includes not only fundamental scientific discoveries but also a rich philosophical dialogue that continues to inspire scientists, philosophers, and thinkers around the world.

The enduring fascination with Schrödinger’s cat and other thought experiments reflects the profound impact of his work. As we continue to explore the boundaries of quantum mechanics and the nature of reality itself, Schrödinger’s insights remain a cornerstone of scientific inquiry and a valuable resource for understanding the complexities of our world.

Further Developments and Impact

The impact of Schrödinger's work has been far-reaching, influencing not only the field of quantum mechanics but also various other scientific disciplines. His ideas have been adapted and expanded upon by generations of physicists and scholars, pushing the boundaries of our understanding of the microscopic world.

In recent decades, the principles of quantum mechanics, first articulated by Schrödinger and others, have found practical applications in areas such as quantum computing, cryptography, and precision measurements. Quantum computers exploit the superposition and entanglement phenomena described by Schrödinger's equation to perform complex calculations exponentially faster than traditional computers.

For example, Schrodinger's wave concept paved the way for quantum optics, a field that has led to breakthroughs in laser technology, atom trapping, and quantum teleportation. These technologies have a wide range of applications, from medical imaging to secure communication networks. The theoretical framework developed by Schrödinger has also played a crucial role in advancing our understanding of condensed matter physics, where quantum effects are crucial for explaining phenomena like superconductivity and quantum Hall effect.

Interdisciplinary Applications

The interdisciplinary nature of Schrödinger's work has inspired collaborations across different scientific fields, fostering a holistic approach to understanding the natural world. His ideas have been applied to the study of molecular biology, ecology, and even economics, where they offer new perspectives on complex systems and emergent behaviors.

In molecular biology, Schrödinger's insights on the informational content of DNA have led to a deeper understanding of genetic processes and evolutionary mechanisms. His concept of a self-reproducing molecular machine has influenced the field of synthetic biology, where researchers are designing artificial molecules and organisms to perform specific functions. This work holds promise for developing novel medical treatments, biosensors, and bioenergy sources.

Influence on Philosophy and Popular Culture

Schrödinger's contributions have also transcended the realm of scientific discourse, leaving a significant mark on philosophy and popular culture. The thought experiment known as Schrödinger's cat, for instance, has become a cultural icon, appearing in countless books, movies, and online media. It serves as a powerful illustration of the counterintuitive nature of quantum mechanics and the challenges posed by interpreting its implications.

Philosophers have extensively debated the implications of quantum mechanics on our understanding of reality and consciousness. Questions abound regarding the nature of time, free will, and observer bias. Schrödinger's work has encouraged a reevaluation of deterministic views of the universe, fostering a more open-minded and inclusive scientific dialogue.

Modern Relevance and Future Directions

The ongoing relevance of Schrödinger's ideas underscores the enduring importance of his work. As we navigate the complexities of the 21st century, from climate change to technological disruptions, his insights continue to provide valuable tools for addressing these challenges.

Looking ahead, there are several frontier areas where Schrödinger's legacy will likely play a significant role. For instance, the study of black holes and the quest for a theory of everything are poised to benefit from the deeper understanding of spacetime and quantum phenomena. Moreover, as we strive to build sustainable and resilient societies, Schrödinger's approach to understanding complex systems and emergent properties could offer valuable insights.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the contributions of Erwin Schrödinger to the field of physics, and by extension, the broader scientific community, are nothing short of transformative. From his foundational work in quantum mechanics to his thought-provoking philosophical writings and culturally impactful thought experiments, Schrödinger’s legacy continues to influence and inspire us.

As we delve deeper into the mysteries of the universe and tackle the complex challenges of our world, Schrödinger’s insights remain a beacon of innovation and curiosity. His work serves as a reminder of the power of interdisciplinary thinking and the importance of questioning our assumptions about the nature of reality.

Louis-Paul Cailletet: Pioneer of Gas Liquefaction

Introduction to a Scientific Revolutionary

Louis-Paul Cailletet, a French physicist and inventor, made groundbreaking contributions to science in the 19th century. Born on September 21, 1832, in Châtillon-sur-Seine, France, Cailletet is best known for his pioneering work in gas liquefaction. His experiments in 1877 led to the first successful liquefaction of oxygen, a feat that revolutionized the fields of cryogenics and low-temperature physics.

Early Life and Education

Cailletet grew up in a family deeply involved in industrial ironworks. His father owned an iron foundry in Châtillon-sur-Seine, where young Louis-Paul developed an early fascination with metallurgy and chemistry. He pursued formal education in Paris, studying under renowned scientists who sparked his interest in gas behavior and phase transitions.

Influence of Industrial Background

Managing his father’s ironworks provided Cailletet with practical experience in high-pressure systems and industrial chemistry. This hands-on knowledge proved invaluable when he later designed experiments to liquefy gases. His work in the foundry also exposed him to the challenges of blast furnace gases, which further fueled his scientific curiosity.

The Breakthrough in Gas Liquefaction

On December 2, 1877, Cailletet achieved a historic milestone by becoming the first scientist to liquefy oxygen. Using the Joule-Thomson effect, he compressed oxygen gas and then rapidly expanded it, causing the gas to cool and form liquid droplets. This experiment debunked the long-held belief that certain gases, dubbed "permanent gases", could never be liquefied.

The Joule-Thomson Effect Explained

The Joule-Thomson effect describes the temperature change of a gas when it undergoes rapid expansion. Cailletet leveraged this principle by subjecting gases to extreme pressures before allowing them to expand suddenly. This process lowered the temperature sufficiently to transition gases like oxygen into their liquid states.

Competition with Raoul Pictet

Cailletet’s achievement was not without competition. Swiss physicist Raoul Pictet also worked on gas liquefaction using a different method involving cascade cooling. Although Pictet reported his findings slightly earlier, the Académie des Sciences awarded priority to Cailletet, recognizing the superiority and efficiency of his approach.

Expanding the Frontiers of Science

Following his success with oxygen, Cailletet quickly turned his attention to other gases. Within months, he successfully liquefied nitrogen, hydrogen, nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide, and acetylene. These accomplishments demonstrated the universality of his method and solidified his reputation as a leader in low-temperature research.

Publications and Scientific Recognition

Cailletet documented his findings in prestigious scientific journals, including Comptes Rendus. His papers on gas condensation and critical points became foundational texts in the study of thermodynamics. In recognition of his contributions, he received several accolades, including the Prix Lacaze in 1883 and the Davy Medal in 1878.

Election to the French Academy of Sciences

In 1884, Cailletet’s peers elected him to the French Academy of Sciences, one of the highest honors for a scientist in France. This appointment underscored the significance of his work and its lasting impact on the scientific community. His research not only advanced theoretical understanding but also paved the way for practical applications in industrial and medical fields.

Legacy and Impact on Modern Science

Cailletet’s innovations in gas liquefaction laid the groundwork for modern cryogenics. Today, his principles are applied in diverse fields, from medical imaging (such as MRI machines) to space technology. The ability to liquefy gases has enabled breakthroughs in superconductivity and the study of materials at extreme temperatures.

Contributions to Aeronautics

Beyond his work in gas liquefaction, Cailletet made significant contributions to aeronautics. He served as president of the Aéro Club de France and developed technologies for high-altitude balloons. His inventions included liquid-oxygen breathing apparatuses, automatic cameras, and altimeters, which were crucial for early aviation and atmospheric research.

The Eiffel Tower Experiment

One of Cailletet’s notable projects involved installing a 300-meter manometer on the Eiffel Tower. This experiment aimed to study air resistance and the behavior of falling bodies under high-pressure conditions. The data collected contributed to a deeper understanding of atmospheric dynamics and furthered advancements in metrology.

Conclusion of Part 1

Louis-Paul Cailletet’s life and work exemplify the power of scientific innovation. His pioneering experiments in gas liquefaction not only challenged existing scientific paradigms but also opened new avenues for research and technology. In the next part of this article, we will delve deeper into the specifics of his experiments, his collaborations, and the broader implications of his discoveries on contemporary science.

The Science Behind Cailletet’s Gas Liquefaction

Cailletet’s success in liquefying gases stemmed from his deep understanding of thermodynamics and the Joule-Thomson effect. This effect, also known as the Joule-Kelvin effect, describes how a gas cools when it expands rapidly after being compressed. Cailletet’s experiments relied on this principle, using high-pressure systems to compress gases before allowing them to expand suddenly, resulting in a significant temperature drop.

Key Components of Cailletet’s Apparatus

The apparatus Cailletet designed was both innovative and precise. It included:

- High-pressure compression chambers to subject gases to extreme pressures.

- A rapid expansion valve to facilitate the sudden release of compressed gas.

- Insulated containers to maintain low temperatures and observe liquid formation.

- Pressure gauges and thermometers to monitor conditions during experiments.

This setup allowed Cailletet to achieve temperatures low enough to liquefy gases that were previously considered "permanent."

The Role of Critical Temperature and Pressure

Cailletet’s work also advanced the understanding of critical points in gases. The critical temperature is the highest temperature at which a gas can be liquefied by pressure alone. Similarly, the critical pressure is the pressure required to liquefy a gas at its critical temperature. By identifying these parameters for various gases, Cailletet provided essential data for future research in physical chemistry and thermodynamics.

Cailletet’s Collaborations and Scientific Network

Cailletet’s achievements were not made in isolation. He was part of a vibrant scientific community in 19th-century France, collaborating with other prominent researchers and drawing inspiration from their work. His connections with chemists, physicists, and engineers played a crucial role in refining his methods and validating his findings.

Influence of Henri Sainte-Claire Deville

One of the most significant influences on Cailletet’s career was Henri Sainte-Claire Deville, a renowned French chemist. Deville’s work on high-temperature chemistry and the dissociation of molecules inspired Cailletet to explore the opposite end of the temperature spectrum. Deville’s emphasis on experimental precision also shaped Cailletet’s approach to designing and conducting his gas liquefaction experiments.

Interaction with the Académie des Sciences

The Académie des Sciences served as a platform for Cailletet to present his findings and engage with peers. His election to the academy in 1884 was a testament to the recognition and respect he garnered within the scientific community. The academy’s validation of his work, particularly in the priority dispute with Raoul Pictet, further cemented his legacy as a pioneer in cryogenics.

Broader Implications of Cailletet’s Discoveries

The implications of Cailletet’s work extended far beyond the laboratory. His successful liquefaction of gases had profound effects on both industrial applications and scientific research. The ability to liquefy and store gases revolutionized multiple fields, from medical technology to space exploration.

Industrial Applications of Liquefied Gases

Liquefied gases became essential in various industries, including:

- Medical field: Liquid oxygen and nitrogen are critical for respiratory therapies and cryogenic preservation of biological samples.

- Manufacturing: Liquefied gases are used in welding, metal cutting, and the production of semiconductors.

- Food industry: Liquid nitrogen is employed in food freezing and preservation to maintain quality and extend shelf life.

- Energy sector: Liquefied natural gas (LNG) is a key component in clean energy and fuel storage solutions.

These applications demonstrate how Cailletet’s discoveries laid the foundation for technologies that are now integral to modern life.

Advancements in Low-Temperature Physics

Cailletet’s work also spurred advancements in low-temperature physics, a field that explores the behavior of materials at extremely cold temperatures. His experiments inspired subsequent researchers to push the boundaries of cryogenics, leading to discoveries such as:

- Superconductivity: The phenomenon where certain materials conduct electricity without resistance at very low temperatures.

- Superfluidity: A state of matter where liquids exhibit zero viscosity, allowing them to flow without friction.

- Quantum computing: Modern quantum computers rely on cryogenic cooling to maintain the stability of qubits.

These developments highlight the enduring impact of Cailletet’s contributions on cutting-edge scientific research.

Challenges and Controversies in Cailletet’s Career

Despite his groundbreaking achievements, Cailletet’s career was not without challenges. The scientific community of his time was highly competitive, and his work occasionally faced skepticism and controversy. One of the most notable disputes was with Raoul Pictet, who claimed to have liquefied oxygen before Cailletet.

The Priority Dispute with Raoul Pictet

The rivalry between Cailletet and Pictet centered on who first successfully liquefied oxygen. While Pictet reported his results slightly earlier, the Académie des Sciences ultimately sided with Cailletet, citing the robustness and reproducibility of his method. This decision was influenced by several factors:

- Methodological differences: Pictet used a cascade cooling method, while Cailletet employed the Joule-Thomson effect.

- Experimental rigor: Cailletet’s approach was deemed more systematic and reliable.

- Peer validation: Cailletet’s findings were more widely replicated and accepted by the scientific community.

This dispute underscores the competitive nature of 19th-century science and the importance of methodological transparency in research.

Overcoming Technical Limitations

Cailletet’s experiments were not without technical hurdles. The high pressures required for gas liquefaction posed significant engineering challenges. He had to design custom equipment capable of withstanding extreme conditions, which often involved trial and error. Additionally, measuring and maintaining the low temperatures achieved during expansion required precise instrumentation, which was not always available at the time.

Despite these obstacles, Cailletet’s perseverance and innovative problem-solving allowed him to overcome these limitations and achieve his scientific goals.

Cailletet’s Later Years and Lasting Legacy

In his later years, Cailletet continued to contribute to science and technology, though his focus shifted slightly from gas liquefaction to other areas of interest. His work in aeronautics and atmospheric research remained a significant part of his legacy, demonstrating his versatility as a scientist and inventor.

Contributions to Aeronautics and Atmospheric Research

Cailletet’s passion for aeronautics led him to develop several technologies that advanced the field. As president of the Aéro Club de France, he promoted the use of liquid-oxygen breathing apparatuses for high-altitude flights. He also designed instruments such as:

- Automatic cameras for capturing images during balloon ascents.

- Altimeters to measure altitude accurately.

- Air samplers to collect atmospheric data at various heights.

These innovations were crucial for early atmospheric studies and laid the groundwork for modern aeronautical research.

The Eiffel Tower Manometer Experiment

One of Cailletet’s most ambitious projects was the installation of a 300-meter manometer on the Eiffel Tower. This experiment aimed to study the effects of air resistance on falling bodies and to measure atmospheric pressure at different altitudes. The data collected from this experiment contributed to a better understanding of fluid dynamics and metrology, further solidifying Cailletet’s reputation as a pioneering scientist.

Death and Posthumous Recognition

Louis-Paul Cailletet passed away on January 5, 1913, in Paris, at the age of 80. His death marked the end of an era in scientific innovation, but his contributions continued to influence subsequent generations of researchers. Today, he is remembered as a trailblazer in cryogenics and low-temperature physics, with his name frequently cited in scientific literature and textbooks.

In recognition of his achievements, numerous institutions and awards bear his name, ensuring that his legacy endures in the annals of scientific history.

Conclusion of Part 2

Louis-Paul Cailletet’s life and work exemplify the transformative power of scientific curiosity and innovation. From his early experiments in gas liquefaction to his later contributions to aeronautics, Cailletet’s achievements have left an indelible mark on multiple fields. In the final part of this article, we will explore the modern applications of his discoveries, his influence on contemporary science, and the enduring relevance of his research in today’s technological landscape.

Modern Applications of Cailletet’s Discoveries

The groundbreaking work of Louis-Paul Cailletet in gas liquefaction has had a lasting impact on numerous industries and scientific disciplines. Today, his principles are applied in fields ranging from medical technology to space exploration, demonstrating the far-reaching implications of his research.

Medical and Healthcare Innovations

One of the most significant applications of Cailletet’s work is in the medical field. Liquefied gases, particularly oxygen and nitrogen, play a crucial role in modern healthcare:

- Respiratory therapy: Liquid oxygen is used in oxygen therapy for patients with respiratory conditions, providing a concentrated and portable source of oxygen.

- Cryogenic preservation: Liquid nitrogen is employed to preserve biological samples, including sperm, eggs, and stem cells, for medical research and fertility treatments.

- Surgical procedures: Cryosurgery uses liquid nitrogen to freeze and destroy abnormal tissues, such as tumors and warts.

These applications highlight how Cailletet’s discoveries have revolutionized medical treatments and improved patient outcomes.

Industrial and Manufacturing Uses

The industrial sector has also benefited immensely from Cailletet’s contributions. Liquefied gases are integral to various manufacturing processes:

- Welding and metal cutting: Liquid oxygen and acetylene are used in oxy-fuel welding and cutting, providing high-temperature flames for precise metalwork.

- Semiconductor production: The manufacturing of semiconductors relies on ultra-pure liquefied gases to create controlled environments for producing microchips.

- Food industry: Liquid nitrogen is used in food freezing and preservation, maintaining the quality and extending the shelf life of perishable goods.

These industrial applications underscore the practical significance of Cailletet’s work in enhancing manufacturing efficiency and product quality.

Advancements in Space Exploration

Cailletet’s principles have even found applications in space exploration. The ability to liquefy and store gases is crucial for long-duration space missions:

- Rocket propulsion: Liquid hydrogen and oxygen are used as rocket fuels, providing the high energy density required for space travel.

- Life support systems: Liquefied gases are essential for providing breathable air and maintaining habitable environments in spacecraft.

- Cryogenic cooling: Advanced space telescopes and instruments rely on cryogenic cooling to operate at extremely low temperatures, enhancing their sensitivity and performance.

These applications demonstrate how Cailletet’s discoveries have contributed to the advancement of space technology and our understanding of the universe.

The Influence of Cailletet’s Work on Contemporary Science

Cailletet’s contributions have not only shaped practical applications but also influenced the trajectory of contemporary scientific research. His work laid the foundation for several key areas of study, including cryogenics, low-temperature physics, and thermodynamics.

Cryogenics and Superconductivity

One of the most significant areas impacted by Cailletet’s research is cryogenics, the study of materials at extremely low temperatures. His experiments inspired subsequent scientists to explore the properties of materials under cryogenic conditions, leading to discoveries such as:

- Superconductivity: The phenomenon where certain materials conduct electricity without resistance at very low temperatures, enabling technologies like MRI machines and maglev trains.

- Superfluidity: A state of matter where liquids exhibit zero viscosity, allowing them to flow without friction, with applications in quantum computing and precision instrumentation.

These advancements highlight the enduring influence of Cailletet’s work on modern physics and engineering.

Thermodynamics and Phase Transitions

Cailletet’s research also advanced the field of thermodynamics, particularly in the study of phase transitions. His experiments provided critical data on the behavior of gases under varying pressures and temperatures, contributing to our understanding of:

- Critical points: The conditions under which gases can be liquefied, which are essential for designing industrial processes and refrigeration systems.

- Equation of state: Mathematical models that describe the relationship between pressure, volume, and temperature in gases, used in chemical engineering and materials science.

These contributions have been instrumental in shaping modern thermodynamic theories and their practical applications.

Cailletet’s Enduring Legacy in Scientific Research

The legacy of Louis-Paul Cailletet extends beyond his immediate discoveries. His work has inspired generations of scientists and engineers, fostering a culture of innovation and experimental rigor. Today, his name is synonymous with pioneering research in cryogenics and low-temperature physics.

Recognition and Awards

Throughout his career, Cailletet received numerous accolades for his contributions to science. Some of the most notable include:

- Davy Medal (1878): Awarded by the Royal Society for his groundbreaking work in gas liquefaction.

- Prix Lacaze (1883): A prestigious French award recognizing his scientific achievements.

- Election to the French Academy of Sciences (1884): One of the highest honors for a scientist in France, acknowledging his impact on the scientific community.

These awards underscore the significance of Cailletet’s work and its recognition by his peers.

Institutions and Programs Named in His Honor

To honor his contributions, several institutions and programs have been named after Cailletet:

- Cailletet Laboratories: Research facilities dedicated to the study of cryogenics and low-temperature physics.

- Cailletet Scholarships: Funding opportunities for students pursuing studies in physics and engineering.

- Cailletet Lectures: Annual lectures and seminars focused on advancements in thermodynamics and materials science.

These initiatives ensure that Cailletet’s legacy continues to inspire and support future generations of scientists.

Conclusion: The Lasting Impact of Louis-Paul Cailletet

Louis-Paul Cailletet’s pioneering work in gas liquefaction has left an indelible mark on the scientific world. His experiments not only challenged existing paradigms but also opened new avenues for research and technological innovation. From medical applications to space exploration, the principles he established continue to shape modern science and industry.

Key Takeaways from Cailletet’s Life and Work

Several key lessons can be drawn from Cailletet’s career:

- Innovation through experimentation: Cailletet’s willingness to push the boundaries of scientific knowledge led to groundbreaking discoveries.

- The importance of collaboration: His engagement with the scientific community and collaborations with peers were crucial to his success.

- Practical applications of theoretical research: Cailletet’s work demonstrates how fundamental scientific research can lead to real-world technologies that benefit society.

These takeaways highlight the enduring relevance of Cailletet’s approach to scientific inquiry and problem-solving.

A Final Tribute to a Scientific Pioneer

Louis-Paul Cailletet’s legacy is a testament to the power of curiosity, perseverance, and innovation. His contributions to cryogenics and low-temperature physics have not only advanced our understanding of the natural world but also paved the way for technologies that improve our daily lives. As we continue to explore the frontiers of science, Cailletet’s work serves as a reminder of the transformative impact that a single individual’s dedication can have on the world.

In honoring his memory, we celebrate not just a scientist, but a visionary whose discoveries continue to inspire and shape the future of scientific research and technological advancement.

John Logie Baird: The Visionary Pioneer of Television

Introduction: The Man Behind the Invention

John Logie Baird is a name synonymous with the invention of television, a technology that has revolutionized the way we consume information and entertainment. Born on August 13, 1888, in Helensburgh, Scotland, Baird was a brilliant inventor whose relentless curiosity and determination led to one of the most transformative innovations of the 20th century. Unlike many inventors of his time, Baird was largely self-taught, combining his passion for engineering with a creative mind that allowed him to push the boundaries of what was thought possible.

From a young age, Baird displayed an aptitude for building mechanical devices. He conducted his early experiments in his parents' attic, often dismantling and reassembling gadgets to understand their inner workings. Though he initially pursued a degree in electrical engineering at the Glasgow and West of Scotland Technical College, his education was interrupted by World War I. Nevertheless, this did not deter him from pursuing his dream.

Baird's journey to creating the first working television system was fraught with challenges. He worked in relative obscurity, often with limited resources, but his persistence paid off when he successfully demonstrated the transmission of moving images in 1925. This historic moment marked the beginning of a new era in communication and entertainment, shaping the modern world in ways Baird could scarcely have imagined.

Early Life and Education

John Logie Baird was the youngest of four children born to Reverend John Baird, a clergyman, and Jessie Morrison Inglis. Growing up in a strict Presbyterian household, Baird was encouraged to pursue academic excellence. However, his health was fragile, and he suffered from frequent illnesses, which often kept him away from formal schooling. Despite this, his keen interest in science and technology flourished during his time at home, where he conducted experiments with electricity and radio waves.

He attended Larchfield Academy in Helensburgh before enrolling at the Royal Technical College (now the University of Strathclyde) in Glasgow. Though he abandoned his studies due to the outbreak of World War I, his time at the technical college exposed him to key scientific principles that would later prove invaluable in his work on television.

After briefly working as an engineer for several companies, including the Clyde Valley Electrical Power Company, Baird’s entrepreneurial spirit led him to explore new ventures. Some of his early attempts at business—ranging from soap manufacturing to jam production—failed, but these experiences taught him resilience and adaptability.

The Road to Television: Early Experiments

Baird’s fascination with transmitting images over distance was inspired by earlier inventions like the Nipkow disk, a mechanical scanning device patented by Paul Nipkow in 1884. The Nipkow disk used a rotating disc with spiraling holes to break down images into lines of light, a basic principle that Baird refined and expanded upon.

Working from a modest laboratory in Hastings, England, Baird tirelessly experimented with rudimentary materials. He used scrap metal, bicycle lenses, and even an old tea chest to construct his first prototype. His early trials involved transmitting silhouette images, and by 1924, he succeeded in projecting rudimentary moving images—though they were blurry and unstable.

Undeterred by skepticism from the scientific community, Baird continued refining his invention. His breakthrough came on October 2, 1925, when he successfully transmitted the first recognizable moving image—a ventriloquist's dummy named "Stooky Bill"—over a short distance. This milestone validated his mechanical television system, proving that live visual transmission was possible.

The First Public Demonstration

On January 26, 1926, Baird made history by conducting the first public demonstration of true television at his London laboratory on Frith Street. Select members of the Royal Institution and journalists were invited to witness the event. Using his improved system, Baird transmitted live moving images of a human face—an assistant named William Taynton—with a resolution of 30 lines at five frames per second.

The demonstration was a resounding success, marking the birth of practical television. Newspapers hailed the invention as a marvel of modern science, though many remained skeptical about its commercial viability. Despite doubts, Baird was determined to push forward, securing financial backing and forming the Television Development Company to further develop his invention.

Competition and Progress

Baird’s success did not go unchallenged. Competing inventors, including American engineer Philo Farnsworth and the corporate-backed efforts of companies like RCA, were also working on electronic television systems. Unlike Baird’s mechanical approach, these rivals used cathode-ray tube technology, which promised higher resolution and greater reliability.

Despite the competition, Baird achieved several world-firsts in television broadcasting. In 1928, he conducted the first transatlantic television transmission between London and New York. That same year, he demonstrated color television and even experimented with stereoscopic (3D) television. His relentless innovation kept him at the forefront of the field, though the mechanical limitations of his system eventually led to its decline in favor of fully electronic alternatives.

Legacy and Later Life

By the mid-1930s, electronic television systems had surpassed mechanical television, and the BBC officially adopted an electronic format for regular broadcasting in 1936. Baird, though disappointed by the shift away from his technology, continued working on improvements, including high-definition and color television.

Baird’s later years were marked by declining health, though he remained an active inventor. He contributed to advances in radar, fiber optics, and even early versions of video recording. He passed away on June 14, 1946, but his legacy as the father of television endures.

The impact of Baird’s work is immeasurable. Television has become a cornerstone of global communication, influencing culture, politics, and education. While modern television bears little resemblance to Baird’s mechanical system, his pioneering spirit laid the foundation for one of the most influential technologies of the modern era.

End of Part 1.

(Note: Continue with the next prompt for Part 2.)

Baird’s Technological Innovations Beyond Mechanical Television

Although John Logie Baird is best known for his pioneering work in mechanical television, his inventive genius extended far beyond this single achievement. Throughout his career, he explored various fields, constantly pushing the boundaries of technology. One of his lesser-known yet significant contributions was in the development of early color television.

In 1928, just three years after his first successful television transmission, Baird demonstrated a rudimentary color television system. Using a technique involving rotating color filters in synchronization with the Nipkow disk, he transmitted color images with red, green, and blue separations. While crude by modern standards, this was the first proof that color television was feasible—a concept that would take decades to refine into the vibrant displays we see today.

Baird also ventured into stereoscopic television, an early precursor to modern 3D television. His experiments involved projecting two slightly offset images to create the illusion of depth. Though the technology was impractical for mass adoption at the time, it showcased his forward-thinking approach and willingness to explore uncharted territories.

Additionally, Baird experimented with infrared imaging, which he referred to as "Noctovision." This system was intended for nighttime viewing and had potential military applications. Though it never became commercially viable, the concept laid the groundwork for later developments in thermal imaging and night-vision technologies used today.

The Transatlantic Transmission and Global Recognition

One of Baird’s most groundbreaking achievements was the first transatlantic television transmission between London and New York in 1928. Using shortwave radio frequencies, he successfully sent a television signal across the Atlantic Ocean—a feat considered impossible by many contemporaries. The broadcast, though low-resolution, featured static images that were reconstructed at the receiving end, proving that long-distance television communication was viable.

This achievement earned Baird international acclaim, solidifying his reputation as a visionary. Newspapers worldwide reported on the event, and scientists began to take television more seriously as a medium with limitless potential. The success of the transatlantic transmission also encouraged investors to fund further research, leading to the establishment of Baird Television Ltd. in 1928.

Despite the technical limitations of his mechanical system, Baird continued refining his methods, increasing image resolution and transmission stability. By 1929, the BBC began experimental broadcasts using Baird’s system, marking the first regular television service in history. Though initially limited to a few hours per week, these transmissions were a major milestone in the evolution of broadcast media.

Commercial Struggles and Competition with Electronic Television

While Baird was making strides in mechanical television, advancements in electronic television—spearheaded by inventors like Philo Farnsworth and Vladimir Zworykin—posed increasing competition. Electronic systems, which used cathode-ray tubes instead of spinning disks, offered superior image quality and the potential for higher resolutions. By the early 1930s, companies like RCA and EMI were investing heavily in electronic television, leaving Baird’s mechanical approach at a disadvantage.

Financial challenges also plagued Baird’s ventures. Despite early successes, his company struggled to secure long-term funding, and production costs for mechanical television sets remained high. The BBC, which had initially partnered with Baird, began testing electronic systems in parallel, eventually phasing out mechanical broadcasts entirely by 1937. The final blow came when the British government officially adopted the Marconi-EMI electronic television standard for public broadcasting.

Though Baird’s mechanical television was ultimately surpassed by electronic systems, his contributions were undeniable. Many of the fundamental concepts he pioneered—such as image scanning, synchronization, and signal transmission—remained integral to electronic television. His work paved the way for future engineers, ensuring that his influence endured even as technology advanced.